Since today’s update is just continuing a conversation from Part 7 (as I couldn’t fit it all into one edition), this may be the first time we’re not starting with a unique quote as a starting point. And, since I’m sure you have no shortage of more important things to keep in mind than my past ramblings, here’s a refresher: last time, we covered the recent/ongoing crypto crash and its similarity to tech; and then we learned about stablecoins, including those backed by fiat currencies, commodities, cryptocurrencies, and finally algorithms. I voiced my immediate concern regarding algorithmic stablecoins, and that’s where we’re picking up today. Here we go!

LUNAr Eclipse

We don’t need to look far for the vindication of my algorithmic-stablecoin-induced cringing. When volatility rears its ugly head, even the most well-thought-out asset allocation, portfolio hedging, or…wait for it…algorithmic-trading strategy may not perform as expected. One stablecoin that recently (and now infamously) made headlines was known as terraUSD (aka “UST”). Here’s a quote that perhaps most simply and concisely explains how it was supposed to have worked:

“UST stabilized prices at close to $1 by linking it to a sister token called luna through computer code running on the blockchain — essentially, investors could “destroy” one coin to help stabilize the price of the other.”

So, the value was supposed to have been controlled by regulating the supply and demand of the two tokens. This article analyzes how this Terra-ble (I had to) situation unfolded, but here’s a real-time perspective on the decline: In early May, Luna (the sister coin) was trading at $85 per token. “By May 11, however, the price of the asset had dropped to $15. And, 48-hours on, the token has lost 99.98% of its value currently trading at a price point of $0.00003465.”

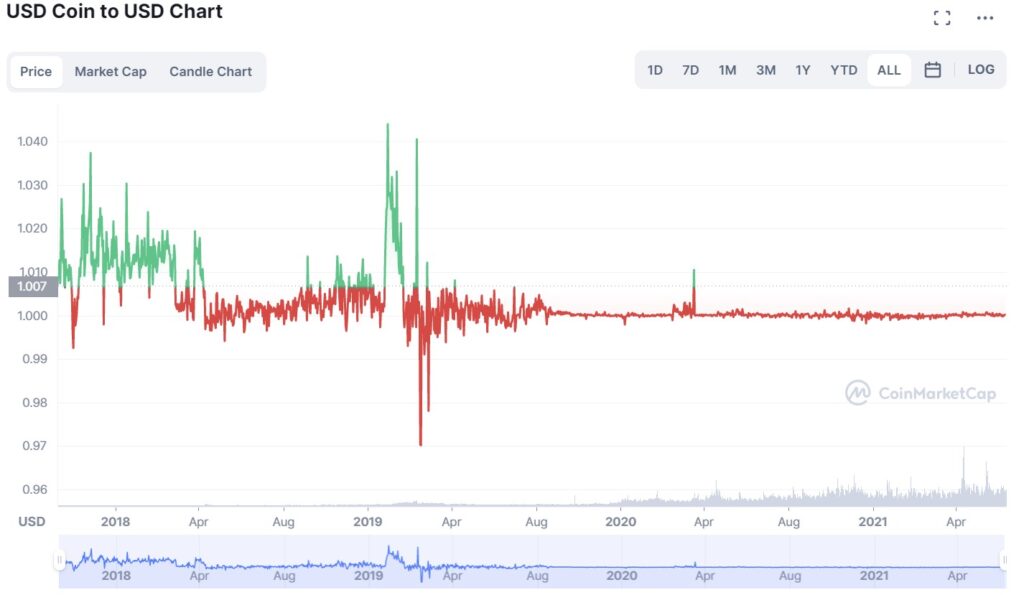

How did that work out for the “dollar-pegged” UST side of the equation? Not well – to put it mildly. In a classic pattern we saw with other investment catastrophes in The Rub: Parts 1 and 2, the below chart shows how UST worked…until it didn’t.

Source: CoinMarketCap

Sunspots

While recent months have been a time of rough sledding for holders of TerraUSD/Luna (and crypto in general), it’s also a period that has provided real-life stress testing of other stablecoins. And although it’s interesting to examine blowups like the above to see what went wrong and what we can learn from them, I don’t think the TerraUSD/Luna collapse is a) particularly concerning or b) indicative of broader stablecoin issues. It may just be confirmation that algorithmic stablecoins aren’t a good idea. I have the benefit of hindsight in this situation, but the outcome doesn’t seem surprising (though I’m sure some people and their crypto wallets are both surprised and VERY disappointed).

According to a Financial Stability Report from the Fed (May 2022), “the stablecoin sector remained highly concentrated, with the three largest stablecoin issuers—Tether, USD Coin, and Binance USD—constituting more than 80 percent of the total market value.” All three are similar in that they are fully backed 1:1 by US dollar assets (actual dollars, Treasuries, etc., though the underlying holdings may actually not be fully disclosed). During the chaos, Tether – the largest of the three tokens – temporarily flinched, at least in terms of where it was quoted on various exchanges. Still, it also continued meeting redemptions at $1.00 (vitally important). There have been a handful of fluctuations in the Tether price-quote history – some above $1.00 and some below $1.00 – but it generally seems to have performed as expected. Solely based on price charts, the other two main stablecoins may have demonstrated even greater stability. Binance USD (the smallest of the three tokens) had temporary price drops in March 2020 and September 2021, and USD Coin has had no deviation from $1.00 since its 2018 inception, according to Coinbase. Hold that thought.

Dude, where’s my fluctuation?

In researching these fluctuations, I stumbled upon the below, which I think is highly misleading at best. I was using Coinbase for basic price-chart comparisons in the above conversation. But I thought it was weird how the USD Coin chart was so perfectly stable (1st chart below). So I checked another source (CoinMarketCap), and voila! USD Coin HAS had some blips in its history, and it seems to have price fluctuation (2nd chart below) similar to the other two coins. And then I found this gem of a quote: “USD Coin is a popular stablecoin that is issued by a domain called Centre which is a joint venture between Circle and Coinbase.” [emphasis mine]

These are supposed to be the same chart. Suspicious?

|

|

So, Coinbase owns USD Coin, and USD Coin has zero price fluctuation in its entire quote history only on the Coinbase site? To give the benefit of the doubt, perhaps since it’s their coin, they could always honor it precisely at $1.00, thus allowing them to quote it as such. But something about it just doesn’t seem right.

Bending the buck

The stablecoin-price-fluctuation conversation reminds me of the 2008 financial crisis, when “breaking the buck” became a major headline related to money market funds. Generally speaking, money market funds are regarded as being cash equivalents, but the difference most investors care about is that money market funds usually pay more interest than cash. Even if they don’t realize it, investors’ other more critical requirement is that their money market shares NEVER lose value (i.e., shares are always priced at $1.00 when bought and sold, which as a reminder is called NAV or “net asset value”).

That kind of sounds like wanting more reward for no risk, right? But why would money market “cash” pay more interest than “cash cash”? If you’ve followed alt.Blend or other writings of The Bahnsen Group for any length of time, you can probably deduce that the higher interest rate paid is only made possible by taking on greater risk, different risk, or some other restriction (like less liquidity). After all, There’s No Free Lunch. And, in fact, in a money market fund, cash is used to purchase underlying investments – usually a portfolio of short-term and high-quality holdings (like treasuries and commercial paper) that balance liquidity and interest. So money market funds are not exactly cash, and they’re also not as liquid as cash.

[As an aside, do you remember those high-yielding savings accounts that paid over 4% interest and were very popular pre-crisis? If so, you may also recall that there was a catch: it took about three days to withdraw your cash. In hindsight, I think the three-day delay was an intelligent design. It allowed the fund time for an orderly sale of underlying assets to raise cash – much like liquidity restrictions and gating we’ve looked at in the Alts world. And with that in mind…]

On September 16, 2008, a large and well-known money-market fund – The Reserve Primary Fund – came under pressure because of the Lehman Brothers collapse (it held about 1.5% of the fund value in Lehman paper, and people were afraid they’d lose money). While the fund was pretty liquid and structured to meet investors’ typical day-to-day redemption requests, it couldn’t keep pace with the level of redemptions in that extreme situation while also keeping NAV at $1.00. Since the Reserve Fund couldn’t sell underlying investments at both the speed and price needed, it fell to 97 cents per share. While on the surface, that may not sound like a huge difference, it essentially meant that “a dollar was no longer a dollar,” and the implications were significant. The Reserve Primary Fund had to freeze operations (and assets) before ultimately entering bankruptcy and ceasing to exist.

And had the FDIC not stepped in with an insurance program to backstop the industry (TLGP), it may have turned into a run on all money-market funds, and 2008 could have been far worse than it ultimately was. To their credit, investment institutions also took steps to help stop the bleeding. At the time, I was about 2.5 years into my career at Ameriprise Financial, and the company stepped in to make all clients whole who had to redeem the Reserve Primary Fund at less than a dollar. That was a wise move, given the alternative of destroying client relationships and trust as we were heading straight into what would become one of the worst bear markets in history.

Bend, don’t break

Related to our crypto discussion, the above reminds us that underlying holdings and structures matter – like how stablecoins are designed and collateralized. I expect the crypto-and-blockchain system to bend during the most challenging times (as we’ve seen with the traditional financial system). BUT it cannot do more than bend if it’s going to live up to the hype and use cases we’ve heard about for years. If the ongoing higher-inflation regime and collapse of Luna are crypto’s “Lehman moment,” then we may now be right in the middle of its full-blown financial crisis. Will it bend, or will it break?

Until next time, this is the end of alt.Blend.

Thanks for reading,

Steve