Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

This week I did something a little unique. I dedicate the Dividend Cafe to the topics du jour in the space of prices, labor, production, and the Fed – basically, all the stuff everyone is talking about (and should be talking about). But rather than it seeming like a single, monolithic essay on it all, I think I have it broken up into bite-sized pieces that will be easier to understand and take in.

We live in interesting times, and if this week’s Dividend Cafe helps you to understand these times better than you did before reading it, I will be a happy man. Let’s dive in and see if that happens.

The worry today and the worry tomorrow

When prices are going higher, and products are not being delivered, and the general system seems to be broken, the short-term concerns that go along with such maladies logically take over. Higher prices, and less supply of goods and services, are both problems in and of themselves in our economic quality of life. And to turn it into a negative feedback loop – the latter basically feeds the former, as I wrote about last week.

I would suggest investors have two things to think about in these times:

Today – rising prices and supply challenges

Tomorrow – excessive indebtedness that inhibits future growth and holds back the standard of living in society

Nothing transitory about these prices

Do I believe that oil and gas prices will stay this elevated in perpetuity? No, not necessarily. They could go higher from here, and they could come down a bit, but I am reasonably confident that even with all the insanity we traffic in these days, the tools are there, and the wherewithal is there to keep us from > $100 oil. “Reasonably” confident (not the same as “totally” confident).

But I do not see prices coming down much for the simple reason that there has not been the investment into new production necessary to “supply” our way out of this. Is that political? Sure, mostly. The movement for decarbonization has most certainly impacted sentiment and capital allocation – both – and the result is that supply is inadequate for demand unless we have a huge demand contraction. Do you follow what I am saying here? We need a crisis – like a COVID lockdown or a recession or some other ghastly circumstance – to bring supply and demand into equilibrium. This is not what we want, and this is not the way to create lower prices.

Is the labor shortage going to get better?

Let us start with an empirical observation – since the federal supplement of unemployment ended, the situation stopped getting worse, and it has begun to improve. But “begun to improve” does not suggest “fully corrected” – not even close. And in fact, there are significant data points that cause one to believe it is not headed to full correction. The declining labor participation force for those 19-26 and those 55+ is a big concern. The “quit” rate last month (all-time high) is a big concern. The seeming contradiction between open jobs and unemployed people is a big concern.

It is nearly impossible to analyze all of this without some social or political biases. I do not mind when my ideological convictions inform my economic views when I can establish cause and effect, but when it is merely speculation that cannot be proven or falsified, I try to leave it out. Do I think some of the data suggestions vaccine mandates on the job are exacerbating the problem? Sure, and I think everyone knows that, even if they support employer vaccine mandates, but it is not provable to any data point, so it isn’t helpful. Do I think some people got used to transfer payments during the COVID and now have a desire to, well, not work? Sure, I do. But I don’t know if that is 10% of the problem or 50% of the problem. No one does.

What I know is that my socio-political leanings and anyone else’s socio-political leanings do not empirically establish the exact weighting of causation here. What we know is a variety of factors have created a mismatch of labor demand and labor supply and that the impact on prices is the logical consequence of this disequilibrium.

Are we sure A leads to B?

Some have raised the concern that the leverage labor presently enjoys pushes wages higher (fair enough) and that eventually, that cuts into the profit margin expansion that equities have been swimming in for so long. Compensation expense is the most significant expense for most companies, especially in a service economy, and upward wage pressure diminishes margins, right?

Profit sensitivity to labor costs is a real thing, no doubt. I expect this will end up having a short-term impact, with that impact felt more profoundly in some businesses than others. But I also believe there is a wildcard at play here, and that is the extent to which employers solve for higher labor costs and lower labor supply with non-labor solutions (i.e., greater automation, digitization, technologization, etc.).

Higher wages that come out of growing productivity in an economy are not a true concern. Higher wages that come from labor supply shortages are. Growing productivity is its own solution in the first scenario. Alternatives to labor are a solution in the second scenario.

You mentioned production once, or 5 million times?

My friend, Louis Gave of Gavekal Research, pointed out this week that in the last 18-24 months of COVID bizarro land, there have been very few deciding to press down on new factories, new training, new oil wells, etc. In other words, demand picked up quickly post-COVID, and supply has a lag, and that lag continues, and it is entirely production driven. Now, the demand side is highly likely to slow down after the sugar high of the pent-up demand relaxes. But whether we are talking about short or long-term periods, we have under-invested in the supply side, and the COVID circumstances made this problem worse.

Is the Fed doing it?

One issue that has come up a lot is whether or not the reason long-term bond rates are still so low is because of the Fed’s bond purchases. It’s a prima facie valid question, but upon further analysis, I think the answer is very clear that the answer is no.

First of all, the Fed is not even 20% of our Treasury market even after this massive balance-sheet explosion. I think it’s safe to view BOJ as Japan’s entire bond market (over 60% is on their balance sheet; basically, they are the purchaser of 100% of new issuance). If 80% of our Treasury bond market wanted a 3%, 4%, 5% yield on their money because of long-term inflation expectations, the Fed couldn’t hold the barn door shut with an army to keep those rates from moving.

Second, the Fed bought $4 trillion of government bonds in QE 1-3, and when they stopped (five years of NO purchases and hundreds of billions of tightening via non-reinvestment), rates went DOWN. This is the most inconvenient truth for the thesis …

The bigger argument for what anchors our long-term rates down is global yield dynamics, but even that screams of disinflationary expectations for the same reason.

M*V

I spoke last week about the P (price level) and the T (supply) in the current economic debate around inflation. If one asks me why long-term rates are so low, domestically and globally, I have nothing better to offer than the V in M*V (money supply X velocity). The decline in velocity will very likely reverse the supply side (T) shocks in the price level (P) at some point. But my suggestion for those excited about such – a decline in velocity because of the current Japanification is no more desirable than rising prices.

A talk about bubbles

One thing I have learned from history – vividly, clearly, without exception – is that markets cannot be sustained when the only motive driving interest is a price gain, disconnected from usefulness, activity, function, purpose, etc. At some point, the argument that “such and such” is a good investment because other people believe it is, doesn’t work. At some point, “such and such” has to have intrinsic value – an internal rate of return – a scarcity – a true use or beauty – that provides sustainable value creation.

How do you invest in these realities?

The desperation for production pushes prices (and margins) higher for industrials, for materials, for energy, and for the sectors of the economy that most need to “produce” more. I expect to see that sector reality reflected in our dividend growth bottom-up selectivity for some time to come.

With fixed income, you simply must focus on quality in the underwriting of the credit positions you have, whether it be Structured Credit, high yield, bank loans, or even private credit (i.e., middle markets lending). There must be seniority of position in the capital structure and adequate underwriting quality because there is no free lunch.

A confidence game

Ultimately, my friends, I leave you with this. People who are confident in the future – who are optimistic about the economy’s direction and the opportunities that lie ahead – save. They save because it is the predecessor to what they really want to do – invest. If you find a way to invest something you have not first saved, please let me know what it is. Confidence in the future produces the incentive to invest. Investing first requires saving. Ergo, if confidence is higher, savings will be higher – the readiness and signal about the future.

I am confident in humanity and not so confident in government (to borrow a phrase from John Mauldin). But I am also confident that the one overshadows the other through time.

Confidence in the human spirit, motivating savings, leading to investment, to capture future growth, profit, and opportunity. To that end, we work.

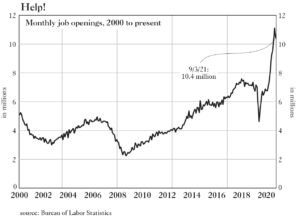

Chart of the Week

The visual aid does the talking here.

Quote of the Week

After last week’s monetary reminder from Milton Friedman about inflation and Irving Fisher’s algebraic lesson about the quantity theory of money, I thought the late, great Wilhelm Ropke on a more cultural definition of inflation would be of use to us:

“Inflation is the way in which a national economy reacts to a continuous overstraining of its capacity, to demands which are extravagant and insistent, to a tendency towards excess in every sphere and all circles, to presumptuous overconfidence in oneself, to a frivolous attempt always to draw bigger checks on the national economy than it can honor and to a perverse desire to combine what is incompatible.”

~ Wilhelm Ropke

* * *

I leave it there for the week. I know some people are expecting me to be laser-focused on the annual USC-UCLA game tomorrow, and I generally am. Though I confess, it has been a long time since I have seen both teams this bad. There have been many years where maybe one of them was this bad (or worse), but the aggregated mediocrity of these teams is disappointing. One may say it has had a deflationary impact on my enthusiasm.

Fight on, and see you next week for a Thanksgiving reflection.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet