Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Most of the attention in the markets this week was on the Fed’s announcements Wednesday – (a) That interest rates aren’t being changed any time soon, and (b) the quantitative easing program launched 20 months ago will start to be slowly eased back later this month with a goal of no additional bond purchases in roughly nine months).

But very little attention is ever paid to why these policies exist, and what their impact is on the various things we investors care about.

In the Dividend Cafe today, we will look at the state of monetary policy, the fiscal policy that has necessitated it (yes, those two things are married right now), and what investment lessons we can extract.

Earnings season is preparing to wrap and it was a solid one. Congress is continuing to bat around legislative things that have not gone the way most people anticipated (or even close). There was huge election news this week that speaks to the current political landscape. And yet through it all, the major investment story of the week may be the one least discussed.

Come on into the Dividend Cafe.

The subject before us

We do not have easy monetary policy because the Fed governors feel that housing prices are too low. They may not like how expensive housing prices are (I doubt that is true, either, but I’ll pretend), but they accept expensive housing because they believe they have bigger fish to fry.

The Fed has a dual mandate, and their language and stated policy concerns focus on those two mandates – price stability, and full employment.

But I think it is fair, objective, apolitical, and candid to say that most people know there is much more at play in Fed policy than merely those two things. Now, unlike some Fed critics, I am happy to concede that one or both of those two things can be impacted negatively or positively around decisions they make.

But my point is that these days, the Fed has become the “manager of the business cycle” – and these days, the Fed has become the facilitator of government debt.

We can say this as a good thing, we can say it as a bad thing, we can say it as anything we want – but we can’t not say it. The Fed has been tasked with making possible the level of government debt we have, and their interventions into the business cycle and tools they have used to do so all feed a policy portfolio that feeds an addiction.

Fed Accord

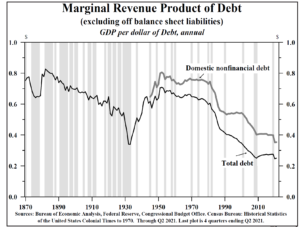

The Fed and Treasury are joined at the hip these days, more than the Greenspan-Rubin era of the 1990s, and more than the GFC era of Bernanke-Paulson. Treasury has to raise a lot of debt to meet Congressional spending priorities, and yet the ever-growing national debt is not creating more “marginal revenue product.” Government spending has skyrocketed, and yet with that debt, economic growth has not increased, it has decreased. This is the heart of economic tension right now.

Fancy Terms

This concept of “marginal revenue product” may or may not seem confusing or complicated to you. I certainly understand that some of the phraseology is not intuitive. But what this expresses is really hard to misinterpret:

The law of diminishing returns is not new, and that is all this is when stated mathematically and economically. But with more specifics, the “additional dollar of GDP generated by an additional dollar of debt” has utterly collapsed. And this has a profound impact on economic growth and investment opportunity, both because of what it is inherently, but also because of how we attempt to treat it.

What is it inherently?

Additional debt is primarily transfer payments, and it is funded through borrowing from present and future productivity of the private sector (tax revenue), which means future productivity of the private sector is, inherently, constrained in productivity and growth by this “pull-forward” of the same. Now, if the debt was creating more revenue than the debt itself represented, then the “productivity” of the debt in the economy would not only perhaps rationalize the debt economically, but create the self-contained payback mechanism (how does a company pay back the debt it uses to finance expansion? from the expansion the debt helped to create).

But inherently our marginal revenue product of debt has only collapsed these last few decades below 1870 and 1945 levels because the debt is not being used to finance economic expansion. Indeed, it cannot do so.

Is all debt created equal?

Of course not. If we borrow money to help pay our loved one’s surgery it may or may not have economic productivity to it, but it has high humanitarian value. If we borrow money to go out drinking at the bar with our friends it has no humanitarian value (I know some of you disagree), and it has no economic productivity to it – the consumption is one and done.

Debt can be used for social reasons, for emergency reasons, or for productive reasons. In some contexts, all three can have merit and benefit, and in some contexts, all three can be problematic.

Government debt is complicated

Government debt is tricky because much of the spending objectives of the government do not and ought not be “productive” in an economic sense of the word. We do not fund a military because it creates jobs; we fund a military because we believe in the vigilant defense of our country. Regardless of what the level of social safety net ought to be (there are respectable opinions on all sides of this issue), the social safety net is not driven by “return on investment” as when a business would make an expenditure commitment; it is driven by a social objective in the society.

Therefore, the question of what size government we as a society want to have is important, because in theory, if we agree to a certain philosophy of government that corresponds to a certain size, we have a rational foundation for funding such. No matter what side you are on of where the size and scope of government ought to be, the reality is that we have not funded it. And I would suggest we haven’t funded “it” in part because we have not agreed to what “it” ought to be (and certainly never will, perfectly).

Seeing is Believing

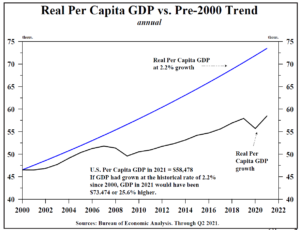

No chart has, to me, captured more of the economic (and social) angst of the last 20 years than this. I understand that wealth inequality and income inequality are said to be the great divide today, but I have studied enough history to know that the periods where inequality becomes problematic are always a response to periods where absolute levels of growth decline.

Put differently, one minds their neighbor getting richer a lot less when they are also getting richer; one resents the pace of their neighbor getting richer a lot more when they are not getting richer.

The interest rate implications

Why do governments like/want/need perpetually low interest rates?

Low rates afford more debt without higher servicing costs.

Japan spends the same on debt interest now as it did in the 1980s, only now their debt is $10 trillion, 250% of GDP (back then it was 60% of GDP).

To a lesser degree, this same dynamic is at play with the U.S. debt levels.

Corporate bailout?

Perhaps the solution is a corporate bailout – not the kind you are used to (where government bails out a corporation; but perhaps corporations can borrow enough (productively) to generate super-charged growth and productivity, adding to the tax base, enhancing GDP, and enabling us to right-size the government balance sheet once we have gotten over the hump? A corporate bailout in reverse.

This is why I talk so much about corporate leverage … Because an UNLEVERED corporate sector that RELEVERS can create a lot of economic growth, and when coupled with government spending modesty, can create a lot of benefit in the economy and in the spending/debt conundrum. But the last time we had a de-levered corporate sector that was due to re-lever, government deficits accelerated like wild, meaning that the economic growth, benefits, and productivity created jobs, created tax revenue, and brought us out of GFC-recession, but did nothing to repair government fiscal imbalances. And in fact, with a now fully-levered corporate sector, the debt levels of government are far, far worse than ever.

This ought to frighten all of us – all negative numbers thrown around regarding government debt are in the context of a non-recessionary economy – of a healthy corporate sector. Wait and see what happens to deficits when that side of the economy cools.

But my point is this – corporate America’s debt may be productive (sometimes it is not), and it may have pushed up economic growth (in many cases the last 15 years it undoubtedly did), but it simply doesn’t have much room to go. Pushing debt levels higher there works from a de-levered level, not an already-re-levered level. This is the conundrum.

Conclusion

This “Japanification” phenomenon is the by-product of decades of work – not something that just happened. But it has exponentially accelerated since the GFC and since COVID, and it ought to color what we believe about rates, inflation, growth, quality, selection, and public policy.

It “ought” to.

Chart of the Week

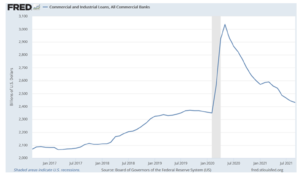

I don’t know if I can show this chart enough. This represents the collapse of loan demand since the Fed-Treasury Accord and hyper debt-to-GDP growth era that began post-financial crisis. Yes, it is why I believe ultimately we face disinflationary realities when on the other side of these supply shocks. But I also believe it speaks to the dynamics that have intensified the need for a new approach to monetary and fiscal policy.

Put differently, what either used to work or what people used to think worked, doesn’t work anymore.

Quote of the Week

“We are perishing for want of wonder, not for want of wonders.”

~ G.K. Chesterton

* * *

I have a few thoughts on where I will take this next week, but I will leave you in suspense (and leave myself with the flexibility to change my mind).

My book comes out Tuesday, and I appreciate those of you who have already shared kind words about it. It is a message that animates me immensely.

To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet