Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I can’t remember what age I was when I thought I had learned everything there was to learn about economics, but it was definitely before I had ever actually managed another real dollar for real human beings. Only someone in their young 20’s could believe they had learned all there was to know about something (actually I can think of a few other groups, too, but I will refrain). What sort of re-triggered my economic education was the combination of the humility that comes with greater maturity (as I got older, and I will add, after I got married, I learned a lot more about how much I still needed to learn), along with the reality of being in the arena. Managing real money for real people forces an interaction with economic theory and practice that is different than what I got from a textbook and a lecture.

When I lecture to high school students about economics now, I do so as a 47-year old managing billions of dollars, humbled daily by the reality of markets and economics. Yet thirty years ago when I faced the other way in the classroom, I thought I knew everything and had found the holy grail of economic certainty.

Today’s Dividend Cafe dives into some of the great economic principles one has to learn if they are to ever learn anything else about economics and finds a comparison with the great investing principle of all time. I hope I will connect the dots well for you.

The readers of Dividend Cafe are not high school students. But one thing we all have in common – the writer of Dividend Cafe, the readers of Dividend Cafe, those sitting in my high school economics class, and those with decades of business and investing experience – is the never-ending need to learn more.

To that end, we work. Now let’s dive into the Dividend Cafe.

The Knowledge Problem

This week I re-read Friedrich Hayek’s masterful The Use of Knowledge in Society, one of the most profoundly significant economic essays ever written. I kid you not that I believe I read it over a hundred times in my late teens and early 20’s. As I was highlighting it this week to prepare for a lecture to high school students I was overwhelmed by how much economic theory and worldview is relevant to investing.

Hayek argues that the allocation of scarce resources (the very practice of economics) requires knowledge, yet knowledge in a society is widely dispersed among many people with no individual capable of acquiring it all. To Hayek, the miracle of markets is that they allow people to benefit and make decisions as the widely-dispersed knowledge of millions of people is reflected in the price mechanism. No central planner – no professor – no pundit – no anointed expert – can ever possess the knowledge necessary to command and control the economy. But millions of people acting with “time and place” knowledge (local, immediate, real, pertinent information, need, and circumstances) can act rationally, and the prices that flow out of the free exchange of such circumstances provide incredible information – signals – to human beings who benefit from that dispersed knowledge.

Therefore, to limit free exchange is to substitute ignorance for knowledge. Better-informed risk-takers are marginalized by less-informed planners.

Human Action

Because I believe economics to be an anthropological field – one rooted entirely in the human person, the human condition, and the satisfying of human needs – I believe economics is essentially the study of human action (around the allocation of scarce resources). I marvel to this day at the profundity of the basis dictum that “humans act” when we consider economic challenges. The entire concept of “stimulating consumption” continues to perplex me, as if humans have ever needed incentives to consume – as if their own natural impulses and wants could ever be otherwise.

Rather, my belief is that economics is driven by production (the supply side) and that humans act in response to incentives. We are already wired to like convenience and quality of life. But our God-given capacity for production, creativity, and innovation – the entire story of economic progress for thousands of years – is essentially at root a story of human action

Why does this matter?

If one believes, as I do, that Hayek was right (price discovery is our imperfect but optimized solution to the knowledge problem, and if one believes, as I do, that Von Mises was right that humans act, then investors are given a paradigm in which to think about how their capital grows.

(1) That which impedes price discovery, impedes the optimal allocation of resources.

(2) Those with the most proximate knowledge of events, circumstances, nuances, and conditions are most qualified to make decisions around them.

(3) Humans not only can be relied upon to act, but incentives matter. Capital not only finds its most rational and best use, but humans make the decisions that incentives and circumstances will drive them to.

I repeat the question – why does that matter?

Any and all attempt at limiting price discovery is negative for investors. The advantage (and miracle) of a free market is how the price mechanism tells us things. The line I used with students just today was, “a price is a signal wrapped in an incentive.” Investors make decisions around a lot of prices (asset prices, input prices, comparative prices, etc.), and obviously, the entire invisible hand of the market itself is busy wheeling and dealing around prices (consumers vs. producers and competitors and laborers and bosses and all the things). But there is another price that matters to investors, as well. And that is the price of money.

When the cost of capital is distorted from its natural rate, almost every decision an investor makes is at least at risk of being distorted. The interest rate is the price of time – the price people put on being separated from their money for a period of time. Very few capital allocation decisions are ever divorced from this dynamic. Expected rates of return, the pricing of risk, the time-value of money – these are all inescapable concepts when we look at investor decision-making (this applies to all of us, all of the time, at varying degrees of self-awareness).

The Fed’s heavy intervention into the economy for purposes of stabilizing financial markets, or dampening the negative impact of the business cycle, or fostering full employment, or helping the government to finance their debt, or whatever else their objective may be (or whatever you may believe their objective to be), no matter how good (or bad) the motivation, no matter the reason, no matter any other peripheral commentary I could offer here, there is no denying that these interventions disrupt price discovery for investors, and in so doing, make harder the underlying task of solving for the knowledge problem.

A quick caveat

One thing many may misinterpret here – my statement that the Fed’s imposition of interest rate prices (versus allowing for the discovery of interest rate prices) does not mean that every time the Fed intervenes, they are drastically going against the will of the market! One thing I think Fed critics have repeatedly gotten wrong is that they have overstated the magnitude of the differential between the “natural rate” and the “imposed rate” over and over again, for a variety of reasons (what drives their miscalculation is is a combination of hubris, well-intentioned error, and just bad luck). The Fed may sometimes lower rates, and if they were to take their hands off the lever, rates may very well belong at the low place the Fed put them.

But my point as one obsessed with price discovery is that we can’t really know, because of the Fed’s hands on the lever.

Pulling it together

I believe the lion’s share of real risk premium – that investment return that exceeds the inflation rate and provides the growth of capital over time to accumulate real wealth – is a by-product of human action. Even when one buys a piece of real estate, it has no value, none, zilch, nada, apart from some human need and activity. A rental office building? There better be some companies doing human action in there to pay the rent. A hotel? Some families better be vacationing or business people traveling. An apartment building? The tenant better have a job to pay their rent. A treasury bond? The government is spending that money they borrow on something, and they can only pay it back with interest from tax revenues they receive on PEOPLE’S ACTIVITY.

You cannot escape this fact in investing. We invest around the profit-making activities of human beings.

The more freedom they have. The more they exchange. The more incentives they have for growth. The more clarity they have for price discovery. ALL of these things drive the opportunity set we have as investors.

And all of these things exist right now in a myriad of pros and cons, opportunities and challenges, risks and rewards, mysteries and revelations.

Next week

I want to do a second-parter here – to take these ideas and concepts and conclusions and put specific investment takeaways around them. Time and space mean that can’t happen right now. But when we look at the national debt, dynamics around the labor force, the price level, credit markets, liquidity in the financial system, incentives to produce and build, and so much more, we have a menu of things to analyze and understand that are at the heart of the investor journey for many years to come.

I want all of us to understand the economic laws and principles that drive all of this.

But I also want us to apply it right. To that end, we work. Part 2, next week. The investment application of human action and price discovery in the 2021 context.

Chart of the Week

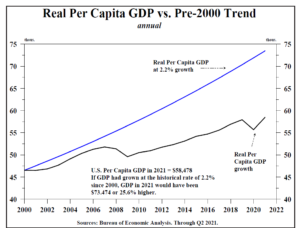

A great challenge of the day is to examine why this may be.

Quote of the Week

“Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment, and he betrays you instead of serving you if he sacrifices it to your opinion.”

~ Edmund Burke

* * *

A very big week lies ahead for The Bahnsen Group. Earnings season is in full effect. There is a fun Dividend Cafe to follow up next week. And we remain at your beck and call as we navigate the events of the day, Humans act, and that includes us.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet