Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I wouldn’t say that I like this, but I would say that I understand it. But last week’s Dividend Cafe was, in just a few days, the most widely read Dividend Cafe I have ever written. I hope that is because clients and readers flocked to the philosophical takeaways of a deeper reflection on bear markets like the one we are in now. But I know that the ratings of financial TV networks skyrocket higher in bad times and that it has a lot more to do with the reality of human nature than anything else. Fear gets clicks and views.

I don’t do fearmongering. My Dividend Cafe last week was actually the opposite of fearmongering. I sought to present the highly rational case for a real glory in the aftermath of bear markets for investors who behave well. Nevertheless, I can understand that the general interest in the topic is largely related to the fear and emotion that goes with the uncertainty of the moment.

This week I am keeping the topic alive, partially because the current bear market did not end in the last five days but also because there is more to be said about the history of all this and the future. And I believe you will find both illuminating in the uncertainty of the moment.

So let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

This easy stock market

When the market goes up from 2009 to 2021 (a 13-year time period) every single year but one (a very modest drop in 2018) it is easy to refer to this as an “easy” period for stock investors. And indeed, in those thirteen cherry-picked years, the market was up +16% per year, a massive premium to normal historical returns.

Even when you do a little more intellectually honest analysis, starting at the beginning of the new century, you still get a pretty darn good return of 9.1% per year (average), with $1 turning into $5 after 22 years of compounding.

But to say this has been “easy” sort of ignores a whole lot of reality along the way. Let’s pull out our history books.

The bear has its own bedroom in 21st century markets

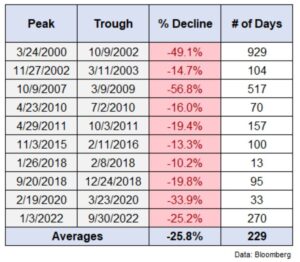

The massive returns in the stock market since the Great Financial Crisis can distort the history of what market investors have experienced since the turn of the century in terms of equity volatility. Bear markets, “almost bear markets,” and double-digit corrections have been quite frequent,

*A Wealth of Common Sense, Oct. 4, 2022

A trip down memory lane

You will note that in late 2002/early 2003, -14.7% proved not to be a bear market but rather a hiccup in the early innings of the bull market recovery that began in 2002 and lasted through 2007. Nevertheless, a nearly -15% sell-off in 104 days can feel like a bear market and was riddled with people sure it was signs that the market wasn’t yet ready to recover. The market would double from the October 2002 bottom to the end of that bull market run (that ended when the Great Financial Crisis found us).

If you look above, you will note in the spring/summer of 2010, there was a -16% drop over 70 days that never quite got to bear market territory, and in late 2015/early 2016, there was a -13% drop that lasted just a hundred days. The former was the initial Greek debt pandemonium, and thrown in there was a “flash crash” that saw markets drop half of that in just hours. It also was so close to the GFC that we were all, shall we say, tender. A sincere paranoia that the horrors of 2008 were coming back lingered. Markets would rally in a tear the second half of the year. The 2015/early 2016 sell-off seems like yesterday to me. China’s foreign exchange reserves were collapsing, significant fears about a China-induced global recession were everywhere, and the Fed was saying at the time they were going to raise rates four times in 2016 (turns out, they didn’t). The markets had their worst January in history, but by mid-February, some global central bank coordination in FX markets caused a magical reversal. The rest is history.

Go back up to the chart again. In summer of 2011, we got an “almost bear market” when Europe’s financial system proved to be far more dire than understand (excessive indebtedness in Greece, Portugal, Italy, Ireland, and Spain wreaked havoc in Europe and created a contagion effect in the U.S. as our investment banks were full of exposure). Additionally, the U.S. was in political gridlock on spending and debt, U.S. credit ratings were downgraded, and I think there was some degree of frustration that USC had a really good team entering fall camp and everyone knew they were barred from postseason play due to severe unfairness from the NCAA. It was not a good summer or a good backdrop for a ten-year wedding anniversary trip. But in the fourth quarter of that year, we rallied +20% and ended the year flat. All in the second half of the year – a bear market, then a bull market. Markets dare us to do dumb things.

Also note in more recent times, the fourth quarter of 2018 gave us an “almost bear market.” Since I have used that expression twice now, perhaps it is a good time to point out that -20% is labeled a bear market in our world and -19.8% is not. I will let you decide how much sense that makes. But the 2018 sell-off lasted 95 days and ended when the Fed suddenly and shockingly reversed monetary tightening (and a “phase one” trade compromise was reached with China).

The -34% drop in one month in March 2020 is in most of our memories, as the world was shut down around the onset of the COVID-19 virus. The story there is as much the V-shaped recovery as it was violence of the sell-off amidst all of the uncertainty. I have long advocated the belief that markets understood COVID throughout 2020 and 2021 better than anyone else did.

And now this one

As I type this, the S&P 500 is down -22.3% from its early January all-time high. Unlike most bear markets, this one has not come from declining earnings (yet), but rather a quite substantial re-pricing of equity valuations as the forward multiple in the S&P has basically come down from 22x to 17x. The Dow has done a little better, the Nasdaq has done a little worse, and most international equity indices are also in bear markets (yet without the benefit of a massive 2009-2021 return preceding this bear). But this is a textbook bear market, and we don’t know when it will end. More on that later.

Nasdaq Reality

The Nasdaq’s bear market makes this S&P sell-off look tame, down well over 30% in less than a year, and now with a compounded return since March of 2000 of just barely 3.75% per year (less than the current Treasury bond yield).

Let me re-state this. In a period of time where Technology has outperformed the expectations of every man, woman, and child on the planet, where world-changing revolutionary innovations have come to market and become trillion-dollar success stories, the aggregate return from the cherry-picked start and end dates of March 2000 to October 2022 has been on an annual basis 3.75%, what one expects from a savings bond these days.

There are periods of 15-20% annual returns in there. It has been a stellar period for tech. How is this mathematically possible that annual Nasdaq returns have been so bad? Well, I am starting just before a nasty and long bear market began, and I am ending (present tense) in a bear market trough (a low level that may or may not go lower). This is what bear markets do – they rewrite returns – they create math that can be highly problematic for an index like the Nasdaq.

Recap

The market got cut in half TWICE in the first decade of this new century.

The market had SIX occasions to be down between -10% and -20% in the second decade of this new century.

The market has had TWO bear markets in the last 30 months alone after no bear market for over a decade.

So we have had FOUR bear markets since the 21st century began, yet only had two bear markets from 1977 to 1999 (well, we were really close in 1990, but technically the only -20% drawdowns were in the double dip recession of the early 1980s and then the massive sell-off in 1987).

It was a volatile ride in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s with some pretty darn good results when all was said and done.

It has been a volatile ride in the 2000s with some pretty darn good results when all is said and done.

Volatility ain’t just a word that starts with V

The up-and-down movements have become more pronounced around a new regime of monetary instability. Markets became more addicted to easy money, which made risk assets more valuable but enhanced vulnerability to boom-bust cycles and re-pricing of risk assets. Down years have become “more down” and while busts have ended quicker, they have been more violent.

The slow pain of a declining earnings cycle drove markets lower in old-fashioned bear markets, and that was usually a more drawn-out process. The sudden pain of monetary policy shifts or exogenous shocks has been the defining hallmark of the new bear markets, more violent but less drawn out.

Bottom line – we are in a regime of increased instability around excessive monetary interventions, which both shortens the pain of bad market cycles and worsens them. More. Volatility. More. Unpredictability.

The size and shape of this bear

The almost +20% rally of the U.S. dollar is at the heart of the current bear market. Standard re-pricing of over-priced assets was inevitable, but even after that dynamic ran its course, a host of economic and market complexities persist. At the same time that a host of geopolitical and economic problems come to the surface, the Fed has taken a ton of [dollar] liquidity out of the financial system, resulting in knock-on effects that hurt U.S. companies with large international revenue streams.

Maybe the Fed reinjects liquidity in the financial system. In fairness, ALL liquidity crises of my lifetime have been met with central bank interventions, so one can hardly be blamed for assuming that is coming again. Maybe there is a central bank coordination coming.

And maybe not. All I can say is that with the valuation re-pricing behind us (or at least a good chunk of it), the story now is about liquidity in the financial system. It can’t be talked about in a meaningful or coherent way because it is complicated, and most people wouldn’t understand it if they were talking about it. But it is the present and future component of this bear market that will matter.

Bad news lingering

It is popular to obsess over the Fed raising rates either 50 or 75 basis points in a given month, or a Fed Funds rate at 4% or 4.5%, as the major catalyst for market pain (fun fact sidebar: the Fed Funds rate was between 5% and 6% from 1995-1999; the market tripled in those five years). Some may get the impression the only thing that matters at all is the Fed Funds rate if they, well, read financial media and watch financial television.

But I am here to cheer you up by saying there are all sorts of other bad things that could happen to markets, too.

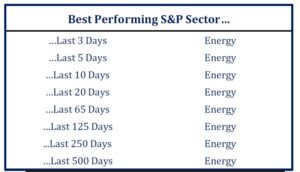

- What if OPEC+ decided not to sell the U.S. oil anymore? Sure, that would explode the profits of U.S. oil companies, but it would push oil prices through the roof and surely hammer other parts of the U.S. economy. It is highly unlikely, but the odds are not 0%. Is that ever discussed?

- U.S. pension funds remain substantially underfunded (6.8% of their income on average, with some states much better and some states much worse). Many of these pension funds jumped into the ESG movement just in time for technology to tank and energy to take the lead in the market. Returns are too low, funding is too low, and pension commitments are too high. Healthcare costs that accompany pension commitments are skyrocketing (who could have seen that coming?). The capacity to raise taxes to solve for this (politically or economically) is almost non-existent. Something has to give, and the uncertainty of this lingers.

- As mentioned many times this year here and in The DC Today, the earnings expectations for markets by which we measure present valuations are still pretty darn sanguine. Are corporate profits super-duper exposed to downward revisions, or just a little exposed to downward revisions? I do not know the answer to that, but I do know it is a downside risk for markets.

Good news and bad news

The good news out of this bear market in stocks AND BONDS is that expected returns on a go-forward basis are now higher. 2022 will likely prove to be the worst year for bonds in history. And to bring back a higher yielding asset class into the toolbox of portfolio construction going forward adds diversification,

The bad news is that none of that is true right now. Stocks and bonds are not diversifying each other right now because they are correlated to each other almost perfectly at this moment. And worse, that correlation is all to the downside.

But they will de-correlate soon enough. And two major asset classes where one of them does not offer a 0% forward return as its BEST case is a good thing. The forward position for bonds is far better than it has been any year of my career, and even if I prefer the growth of income equities represent, the diversifying and risk-mitigating impact of this math reality is a very good thing.

When will it all be over?

The bear market will end before everything is good again.

The bear market will end when markets see the future Fed pivot on the horizon. Some think they will be dug in for some time. Others think the end of this tough talk is on the horizon. I believe it will be when bond yields peak and reverse, and the dollar declines with it.

But it will be before it feels like things are good again. Markets are discounting mechanisms, always and forever.

Conclusions

Is it true that the Fed has a lot to do with when this bear market will end? Well, sure, but that is only true because of the greater interventionist stance of the nation’s central bank across the economy. It is not true that it should be this way, but it is true that dollar liquidity issues, earnings expectations, bond yields, and foreign country positioning relative to U.S. monetary policy are all, to some degree, in the hands of a few central bankers.

The Fed will not need to be dovish for these things to change. They will move monumentally at the mere hint of Fed alteration in stance, rhetoric, and focus.

Then, we can go back to the world we were in before. Which is the same one we are in now and have always been in. A world of up-and-down volatility, unpredictability, and various dimensions of instability. And one where the optimists win, bigly.

I don’t know and don’t especially care if things reverse in one month or one year. They will reverse. I do want to capitalize on the bear market by reinvesting dividends at these prices and adding new money, but I will not beclown myself or damage my clients by making a false prediction that can only come true by being lucky.

The most discredited charlatan class of no-skin-in-the-game frauds in American life are professional perma-bears.

P.S.

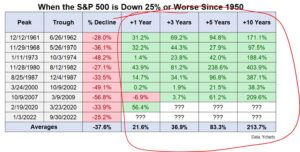

How can things be better in the future when they feel so bad now? You will have to ask history …

Chart of the Week

Remember when everyone was predicting this a while back? Yeah, me neither.

*Strategas Research, Technical Strategy Report, Oct. 6, 2022, p. 1

Quote of the Week

“Look at market fluctuations as your friend rather than your enemy; profit from following rather than participating in it.”

~ Warren Buffett

* * *

I am leaving the conclusion short for time constraints reasons, but I hope you get the idea. Things have been tougher than we romantically remember them. And yet, here we are. The future belongs to the optimists. But we have a volatile time ahead. And we intend to guide each step along the way with prudence, discipline, and care. To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet