Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I love the topic of this week’s Dividend Cafe. I believe one of the most powerful people in global finance gave me the chance to address a topic today that desperately needs to be addressed. And through this topic, we have profound takeaways to inform our understanding of economics, and to apply such understanding to the emphases we put in our portfolios.

I will leave the introduction there, and hopefully with enough suspense to push you into the Dividend Cafe. This is important stuff.

|

Subscribe on |

When Central Bankers Tell the Truth

Haruhiko Kuroda, the governor of the Bank of Japan, said something two weeks ago that I think should be noted by every market participant under the sun.

“The Yen’s depreciation has a more beneficial impact than a negative one, so long as the depreciation is gradual and in line with the nation’s economic fundamentals.”

There is something striking in this admission, and almost impressive in its honesty. The obvious part is a central banker whose job is, to some degree, to defend his nation’s currency, saying that the depreciation of value of that currency is a good thing. But the less obvious takeaway is the caveat that he offered – “so long as the depreciation is gradual.” And then, the final wonderment is that second caveat – that depreciation is a good thing “if in line with economic fundamentals.”

It can be a good thing if I go to the hospital as long as it is because I am unhealthy?

But I digress.

“So long as the depreciation is gradual.” What do you think he meant by this?

Killing You Softly

There is a sense in which one can argue that economic impact is softer when currency moves are “gradual” (shock factors, stability, reaction function, etc.). But at the end of the day, the good central banker is admitting what is a fundamental fact of human nature: People do not get up in arms when bad things happen to them slowly; they only lose their cool when bad things happen suddenly and noticeably.

It was a political statement, not an economic one. It was a derivative of the point I have been making about inflation my entire career:

People lose their marbles over deflation.

People lose their marbles over big inflation.

People don’t even notice “modest” inflation.

Currency depreciation is not the same thing as inflation, but it is a cousin. The point I am making in similarity here is the tactical assumption in the statement: That gradual depreciation is somehow superior.

A gradual rusting of one’s pipes in their home plumbing does not make the eventual pipe malfunction any better. An unpleasant destination is not made better by the speed in which one gets there.

I want to use weight analogies (which are often helpful in finance, I find, plus it motivates me to try and practice the same discipline in my food/exercise that I do exercise in my financial affairs, but apparently not so well) – but the problem with a weight analogy is that a sudden weight loss or weight gain in bio-health generally means something else going on (causatively) that is problematic. Where the analogy does hold is that those who end up 25 pounds overweight are not in a better position if they did so 2 pounds per week for 12 weeks or one pound per week for 25 weeks. Once 25 pounds overweight, there is no comfort taken in the speed at which it happened when you are trying to fit into your suit.

Central Bankers’ Purpose in Life

My friend, John Mauldin, used to write that when one becomes a central banker they get taken into a backroom and programmed to, always and forever, exist to fight deflation. The great spectacular implosions of banking and finance over the last 150 years have been deflationary busts, and they are more or less why we have central banks. I understand we have a “dual mandate” that refers to “price stability” in the charter of our Fed, but no one ever asked a central banker to come be an inflation foe. The wink and nod of central banking is to “let inflation be gradual.” It is deflation that spirals. It is deflation that lacks a policy-effective response once the spiral picks up speed. It was deflation that the Great Depression created. It was deflation that was at the heart of Japan’s burst 30 years ago. It was a deflationary spiral at the heart of the great financial crisis.

What did the guru of modern economic thought have to say on the subject?

“Thus Inflation is unjust and Deflation is inexpedient. Of the two perhaps Deflation is the worse; because it is worse, in an impoverished world, to provoke unemployment than to disappoint the rentier.”

~ John Maynard Keynes

Let’s not limit our discussion to central bankers and 20th-century economists. What would upset you more? Option A – a perpetual decline in your asset prices (stocks, bonds, real estate, business value) whereby the decline leads to a cut in production that further lowers prices, rinse, and repeat. Option B – your vacation and car costs increase year over year.

In the immortal words of Milton Friedman, everyone hates inflation, unless it is their home value inflating.

Central Bankers and Inflation

Does this mean central bankers don’t mind inflation? No, it means much more than that. It means they actually want inflation, provided it is contained enough to not create public outrage.

How do I know this? Because they tell us, in their words, with no ambiguity, ALL THE TIME. What is a 2% inflation target, besides the stated and published monetary policy of the United States central bank? It is a public pronouncement of the intention to cut purchasing power in half every 36 years.

I freely admit that if they did not come out and say it I would still believe that it is their intent. From the currency debasement of the Roman Empire nearly two thousand years ago to modern central banks in all forms, there is “free money” available to the government in the form of inflation. Governments can spend money by borrowing it and can get a good deal by paying it back with money worth less than the money they borrowed. This is all we are talking about here, and it is all we have ever been talking about. But my point is that we have not had to believe that central bankers want moderate inflation merely by induction or deduction – they have been kind enough to explicitly admit so for quite some time.

What does this mean?

Central bankers can control the price of money to some degree, and they can control the quantity of money to some degree, but they cannot control both at the same time (with precision or fidelity to stated policy). Our nation can set its target policy rate, and Japan can set hers, but neither country can really control how the two currencies trade against each other, or trade against other world currencies. And the public does not merely have an interest in the cost of money, the supply of money, the prices of goods and services, but also the value of the currency in which they transact. Now, you may personally not care what the dollar trades against the Euro in your day-to-day life, but I assure you Procter & Gamble and Apple, and Coca-Cola do, and I assure you that you care what they are charging for goods and services.

We are living in an era where multiple policy agendas that are in conflict with one another are playing out before our very eyes. The idea that Japan can gain a policy advantage for itself by weakening its Yen relative to other currencies may seem true for a time, but as the good central banker admitted:

(1) It has to happen gradually or the natives get restless, and

(2) It has to happen without other countries with competing interests deciding to fight back.

Can a weaker Japanese Yen hurt the export competitiveness of China? You bet. Could China decide to weaken the renminbi in response to this, which in turn hurts the U.S.? You bet.

My point is only this: We err in believing that a central bank has the ability to control all the policy objectives they want to control. Even if they had the omniscience needed to get rate policy where they want it for their desired aims (they don’t), and even if they knew how to manage financial system liquidity ideally when it comes to their own balance sheet (they don’t), there is no possible way to know how their policies impact other countries, who then take counter-policy actions, which then change the problem and policy context altogether.

Whack-a-mole

Expect to hear a lot of changing subjects in the context of monetary policy for the rest of your life. Expect to hear of the beauty of currency depreciation from Kuroda today, and the need to strengthen a given currency in a given country at a given time, tomorrow. Expect to hear about how inflation is running hot today, and expect to hear that it is below target tomorrow. Expect to hear each side of these various policy categories as the need of the hour – forever up and down on the teeter-totter – for a long, long time.

This is the by-product of hyper-intervention from central banks, and hyper-discretion from central banks.

And for our portfolios?

Do we have a problem with too much debt in our society or not enough debt? If you believe we do not have enough debt, then my interpretation of Fed policy intentions for years and decades ahead will be wrong. But if you believe there is abundant debt governmentally, corporately, and personally, then the back-room programming of central bankers to, above all else, fight against a runaway deflation, remains the real sine qua non of central banking. Why? Because debt becomes more expensive in deflation and becomes less expensive in inflation. With excessive debt, the cost of it becoming more expensive is fatal. Re-payment becomes challenged (unless you can have a central bank monetize your repayment). More private actors default. Fewer banks lend. Less productive activity happens. Less jobs are created. Rinse and repeat.

As long as the societal condition is that we are over-levered, the central bank bias will be to counter deflation. That is a secular truth.

Conclusion

Cyclically and rhetorically the present bias is anti-inflation. Fair enough. The “speed” of things got away from everyone, as Kuroda accidentally admitted. The giant complexity of post-COVID policy with substantial supply constraints in a period of heavy demand resurgence has changed the present narrative.

But it has not changed the fundamental laws in which we exist. Investors will be wise to keep their eye on that ball.

Gradually. Like a currency being depreciated.

In line with economic fundamentals, as if anyone cares about that anymore.

Chart of the Week

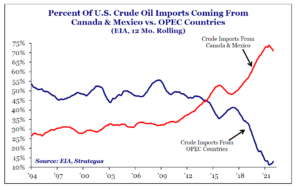

To add a little more color to the frayed relationship between the United States and Saudi Arabia (last week’s topic), note the collapse of the level of oil imports the U.S. receives from OPEC over the last decade. It is not merely U.S. self-production that has caused this, but also a replacement of import needs with other North American countries.

*Strategas Research, Policy Outlook, March 31, 2022, p. 4

Quote of the Week

“Misfortunes one can endure – they come from outside, they are accidents. But to suffer for one’s own faults – ah! – there is the sting of life.”

~ Oscar Wilde

* * *

I am heading out to the New York City office for a couple of weeks. I am excited to bring a more comprehensive Q1 review in DC Today next week and a portfolio-specific recap for clients in WPHR on Wednesday.

In the meantime, may your Final Four wishes come true. And may the greatest college basketball coach of all time go out with a storybook ending. He deserves it.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet