Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Today, I would like to use the last five years to make some broader points about the realities of investing. Evergreen realities are, well, permanent. Yet we find within the last five years some serious bold-faced reiteration of these realities to which I refer (and as you will soon see, there actually is a particular single reality most on my radar this week).

So, in this week’s Dividend Cafe, we will look at the last five years and extract from this little short-term window some big-picture lessons that are sure to matter for more than just the last five years. Consider it part “History” (albeit recent history) and part “Investing 101” …

Jump on into the Dividend Cafe!

|

Subscribe on |

The beginning book-end

Even though I want to start this little trip down memory lane in 2018, it is important to remember some context as we head into the beginning of this five-year trek. The great financial crisis had ravaged global economies and global markets in 2008, and U.S. markets began their recovery in 2009 (in advance of economic recovery). From 2009-2017, the U.S. stock market had not had a negative year (it got close in 2011 and 2015 but still eked out a positive return). Nine years in a row of positive returns when nearly all of those years had either outright economic headwinds or, at best, muted economic growth – and when many of those years did not see shared positivity in global competitor markets. U.S. earnings had recovered well off of their bear market trough. Low multiples became much higher multiples. Corporate profit margins began a long streak of expansion (beyond what skeptics thought could happen). And a sense of corporate reflation offset the challenges of household deleveraging and the poor policy mistakes of federal government expansion. The final year of this post-crisis streak, 2017, in particular, represented the “as good as it gets” moment for investors: +22% returns in the stock market yet without any downside volatility (not even one drawdown of 3% or more throughout the whole calendar year as investors enjoyed a resurgence of small business optimism and hopes circulated, justifiably as it turned out, for a business tax reduction bill by the end of the year).

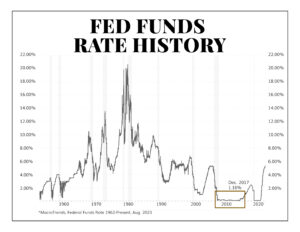

But, you know, interest rates had basically been 0% the entire time. So there was that—0% for years and years and then closing 2017 at a whopping 1.1%.

So, we enter 2018 with that as the backdrop. I chose 2018 as the beginning book-end of this five-year period not because of the convenience of using a five-year interval but rather because it was the first negative return year in markets since the Great Financial Crisis. 2018 saw the Fed attempt to get the fed funds rate off of a 0-1% range, and it saw the Trump administration jawbone with trading partners (most notably, China) around protective tariffs. The two-headed monster of the Fed and the trade war provided some backdrop for market volatility, even as corporate earnings were healthy and even as markets soaked in the victory of tax reform passed in late 2017. The uncertainty of what monetary tightening meant for liquidity in financial markets was enough to spook credit markets, and by the end of the year, it was clear markets were not going to shrug off what the Fed was doing (remember, it was not just rate increases going on but also ratcheting up attempts to reduce bank reserves via quantitative tightening). Now, one could say it wasn’t that bad since markets closed down not even -5%, but it was the first negative year, and at one point in Q4, markets had dropped nearly -20%.

2022 ended up being the next year to experience a negative return (much more negative than 2018). We had a little five-year microcosm bookended by two negative years with three positive years in between. Okay, easy enough. But let’s now connect this to a fuller historical timeline.

Point – Counterpoint

So if we enter 2018 and I tell you, “corporate tax burdens are about to massively decrease, over a trillion dollars is going to be repatriated back onshore, CEO confidence and small business optimism are at their highest spot in well over ten years, and the economy is about to grow the most it has since before the financial crisis,” what are you predicting for 2018 in markets? Some of those things were known entering 2018 (the tax bill had been signed into law), and some were reasonable forecasts at the time. Some were pleasant surprises that were unknown at that time. But all of them proved to be true about 2018.

And 2018 was the first negative year for markets in a decade.

Next, 2019

So if we enter 2019 and I tell you, “the Fed is tightening like crazy, a 1% fed funds rate is likely going to more than double, credit spreads have blown out, the yield curve is inverted, which everyone says guarantees a recession, massive taxes are coming in the form of tariffs in this trade war, and there is even talk of expanding the China trade war to Europe, Canada, and Mexico,” what are you predicting for 2019 in markets? All of those things were true on January 1, 2019.

Very few of them were true just days and weeks later. The Fed reversed course in a shocking capitulation. The trade war simmered (even if not much changed). The yield curve settled and gave what is a more common than people think false alarm. And 2019 would be one of the biggest years for markets in history. From “General Electric can not roll over its debt” to “one of the biggest years in market history. From “the Fed is going to break the economy” to “quantitative easing is back.” From “four or five rate hikes” to “two rate cuts.” And again, a massive year for risk-on just one year after the first negative year in a decade, when all indications were for worse, not better, conditions.

Well 2020 was an easy one to call, though, right?

I would think this goes without saying that 2020 defied predictability, but even then, I do not mean what many probably think I mean. It is one thing to say “no one could’ve seen a global pandemic” coming – and that is certainly true.

And we could add that no one could have seen the societal response that we got even if we had known a pandemic was coming (lockdowns, school closures, restaurant curfews, eating inside but only in structures on a sidewalk, masks when you are walking five feet but not once you’ve got to your table … okay, sorry, I think I have veered off a little here). What I mean is that no one would have predicted the level of social and economic activity suppression that the pandemic was going to generate, let alone the length of time it all lasted (I think some are still kind of in it).

But then that doesn’t even cover the level of policy response we were going to get between the CARES Act, the extension of unemployment benefits, the PPP endeavor, the Earned Income Tax Credit, the $5 trillion of quantitative easing, the 24 months of zero-interest-rate-policy, etc.

So you had an unpredictable event that created an unpredictable response which then brought about an unpredictable policy response.

And again, if I tell you, “Hey, just for pretend, let’s say the world goes through a global pandemic, they shut down the whole world for months, much of the world stays shut down all year, and unemployment triples. GDP contracts the most since the depression, and governments go on a spending and borrowing binge like we have never seen, ever.” What are you guessing markets do?

Because if you guessed, “go down,” it lasted for about five weeks. In fact, with the cultural, economic, and social conditions of society as bad as they had been in fifty years, the market rallied. Stocks ended up a lot.

Space Odyssey 2021

Well, maybe you’re thinking that markets figured out early that COVID was not going to change the world as many had feared, thought mortality was much less than many feared, and that one way or the other, healthy market conditions would resume once the virus passed in a few months. If we are entering 2021 with these predictions out there, what is your guess for 2021?

“I think this year we will see Joe Biden inaugurated as President, with some of his first actions to be shutting down key pipelines and energy plans, announcing intent for a massive tax increase across investment, corporate rates, and individual rates. Before he is inaugurated a disgusting riot will take place at the U.S. Capitol building. And the school closures will last through the entire school year, with a couple variants of COVID coming that we’ll call ‘delta’ and “omicron’ that will put politicians and media virtue signalers in state of hysteria. GDP recovery will underwhelm expectations significantly, student loan deferments and unemployment benefits will be extended nearly all year, and most businesses (the ones who survived and re-opened) will be desperate to find workers).”

Does that series of predictions put warm and fuzzies on your 2021 bingo card? Does it put a +26.9% return in the market on your radar? I didn’t think so.

Now, in this case, a lot of the market return was not despite bad things happening, as much as it was “some of the bad things people predicted not happening.” It really was a mixed bag with some of both at play, but you don’t generally go up 27% because they didn’t pass a $5 trillion tax increase? I mean, they “don’t pass Build Back Better” every year, right?

Everyone predicted 2022 except truthtellers

You know who said interest rates would go up 1% in 2022? The Fed. Everyone else, too, but they were just saying what the Fed themselves said (they had a dot plot of a late 2002 rate of 1-1.5% on the Fed Funds target rate all the way into the spring!). The Fed raised rates 500 basis points, bonds got walloped, inflation soared, the economy re-opened, masks came off on airplanes (highlight of 2022 for me), and for the first time in forever both stocks and bonds were down double digits. Now, if a Nasdaq drop of -34% was so predictable, I ask you, why were there no outflows from the Nasdaq at all until it happened?

And if stocks were dropping because of the inevitability of a recession, why did they not come back up when the recession did not happen?

I do believe that the market surprise in 2022 (higher and longer than expected inflation, higher and longer than expected rate increases) was a by-product of what happened, not a contrarian or surprise response to what happened. But “what happened” itself was entirely unpredicted (find an analyst who had a -25% S&P drop or a 500bp hike in short-term yields on their 2022 forecast; you won’t).

But now it gets easy!

At least we entered 2023 knowing exactly what would happen and exactly what we should do about it! The Fed had tightened so much that a recession was inevitable, job losses were forthcoming, corporate profits would be down -20% (if we were lucky), and even bank failures were on the horizon (big ones)!

So if the S&P was 3,600 in October 2022 and then all of the bad stuff was coming, surely you would have predicted …

4,600 in August 2023?

I didn’t think so.

See my point?

The world is filled with people who:

(1) Make wrong predictions about the future (nothing wrong with this; it is hard to predict the future)

(2) Make wrong calls about what to do regarding their predictions about the future (nothing wrong with this; it is hard to make right calls about what to do when it comes to markets)

(3) Both #1 and #2

Predicting unpredictable events cannot be done; if it could, it would not help investors at all. Time and time again, history teaches that markets confound the wise. Attaching a short-term market outlook to a short-term view of the world gives one a chance to be wrong twice, and it is a chance many take with both hands over and over again.

Conclusion

Long-term financial needs must be solved for with long-term financial solutions. The ebbs and flows of what happens in the world, the economy, geopolitics, and so much more are not a knowable factor in how one solves for financial needs.

And market responses are not knowable either. Markets price future expectations in long before our weather app updates (if you know what I mean). One year, no one is ever going back to the office, and the next year, every company is telling people to get back to the office. It’s a wild world out there. Markets are not irrational – they are just complicated and nuanced and have multi-causal explanations for what happens. Predicting what they will do next has not worked well for many people I have ever seen.

But alas, there is a solution. It is to invest in free enterprise, human action, human ingenuity, and an alignment with your own interests as an investor, even when there will be hiccups, interruptions, zigs and zags, and headline noise. Avoiding momentum traps is a pretty good investor habit, but so is accepting, upfront, as a matter of eternal truth that you cannot predict the future.

And it wouldn’t help much if you could, anyway.

Chart of the Week

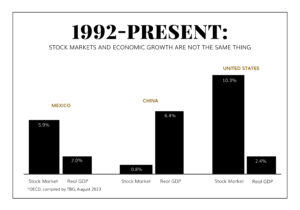

Are economic facts on the ground useful predictors of market behavior? Maybe, you say, not in a one-year period, but over time, sure? Consider China’s complete lack of stock market return for decades, accompanied by the largest economic growth in that same period the world has ever seen. And then compare it to Mexico’s abysmal economic growth contrasted with its stellar stock market performance. The realities to which I speak are true in months, years, and decades.

Quote of the Week

“In an age of acceleration, nothing can be more exhilarating than going slow.”

~ Pico Iyer

* * *

I love this week’s Dividend Cafe. I love reminders of first principles. And I love the renewal of focus on what we can control (analyzing cash flows and company activity) vs. that which we cannot control (how markets will respond to a COVID variant or what politicians will do or say on any given day).

I hope it is a good reminder for you, too, and we welcome your questions and feedback, always.

And, of course, we welcome USC punishing Stanford in the Coliseum tomorrow night. But I will remind my Trojan brethren, the unpredictable has happened before, hasn’t it? Fight on.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet