Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

It has been a volatile month in markets, to say the least. October represented the third consecutive negative month in all three market indices, coming off of a modest downturn in August and September, as well. October did it in more roller-coaster fashion, starting off the month with a 600-point drop in the first few days of the month, only to see that reverse to a +1,000 point increase from October 6’s low to October 11’s high (that’s a pretty quick comeback), only to then drop -1,500 points (no typo) from mid-month to late-month, only to then yet again rally, being up over +1,100 points from the low of last Friday to the time I am typing this just one week later.

Down-up-down-up – it can make your head spin if you dare to tell yourself any of it matters (none of it does).

But the intra-month volatility and the odd twists and turns of the market throughout the year all speak to a bigger underlying dynamic in markets that I have obsessively covered in these very pages all year – the role of monetary policy, financial conditions, and bond yields in driving investor outcomes in this very short term moment. That entire landscape was the heavy focus of our annual week spent with various money managers, hedge funds, and research partners this year (I covered Fed chair, Jerome Powell, last week). The evolution of our annual “due diligence” week has led to a lot more meetings with managers in private markets, as well (equity and credit). Across private and public markets, we got a chance to see what is most on the minds of asset managers at this stage of 2023, and you will be shocked to know it is not a lot different than the same things on the minds of all investors.

And those things are the subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe – the underlying conditions right now creating multiple round trips of a thousand points in the market in just one month. Jump on into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

Putting it into words

I decided a chart was not necessary to communicate this point – that words were perfectly capable of doing it justice – as the 10-year bond yield has gone, so have stock prices gone. The 10-year in early September had gotten as low as 4.25%, and the Dow was sitting at 34,500. A few weeks later, the 10-year was at 4.62%, and the Dow was down to 33,500. Fair enough – a 35 basis point move higher in bond yields and a 1,000-point drop in markets.

Yields paused, then dropped a bit for a few days while markets paused – and then the aforementioned October roller coaster began. Markets dropped another -700 points or so into early October, and the 10-year moved from 4.6% to 4.8%. That yield then collapses back to 4.5% in the aftermath of the Hamas/Israel war (that war in which Hamas viciously attacked Israel, causing American college students to protest in defense of … not Israel), and the market goes up 1,000 points in the same few days. That 4.65% gets its way up to 5% over the next two weeks, and the market drops 1,000 points. Since then, the 10-year has given back 35 basis points (back to 4.65%), and the market is up 1,000 points yet again.

The direction of things

That the market has more or less moved up or down about 1,000 points with each 35 basis points (or so) in the 10-year is not a scientific ratio I would cling on to. It has held for a few round trips over the last month, but the correlation is much more significant around the direction of yields (and stock prices) than it is at the absolute level itself.

It does not do a lot for us to note that the long bond and stock prices are heavily correlated right now. The question is not whether or not the 10-year yield and stock prices are inversely correlated (that is pretty easy to see), but rather why, and for how long, and what are the conditions that will impact those inputs, etc. It’s a pretty easy logical syllogism to say that stock prices are correlated with bond yields. Bond yields are presently volatile; therefore, stock prices will be volatile. One or more of the premises may cease to be true, but as long as they hold, the validity of the conclusion is intact. But looking into the substance of the premises is the subject at hand.

A long bond primer

From our very first meetings with a handful of our taxable bond managers, it was clear that we were going to hear a lot throughout the week about when the Fed would begin cutting rates and what it would take for them to begin doing so. As our first meetings were with pure bond managers, that seems to make a lot of sense – seeing as how their entire asset class largely pivots around the math of interest rates (nothing surprising here). The theme would not change all that much with many other asset classes, either, though, but I digress (more on this later).

And yes, when we look at long-bond yields, it is true that the short-term policy rate matters. If the Fed were to begin cutting their short-term rate, I do suspect the long bond yield would come down, too. However, and this is crucial, the circumstances around rate cuts – the reasons they are happening – are the determining variables in how financial markets will respond. A 5% ten-year yield because economic growth is booming is very different than a 5% yield that comes because of inflationary concerns.

The overnight rate ought to be baked into the 10-year (that is, one would think “baked in” to what investors demand in yield for giving up their money for a ten-year period is, at a starting point, what they would get for giving up their money for 90-days, for example). In other words, an investor (lender) may very well want more to be parted with their money for ten years than for ninety days, but the 90-day cost of separation is at least a good starting point. So we bake into the 10-year bond yield the federal funds rate itself (or, if you prefer, a 90-day T-bill rate) – and then allow for what we call “term premium” – the premium in yield we want above that baseline for “term” – for longer period of separation from our money. Fair enough, right?

But how is that term premium defined? In periods of high inflation, one may want more yield because the purchasing power of their money will have eroded by the time they get the money back. But if one does not believe inflation will be sustained, they may not require as much premium for inflation concerns. Modern financial markets give us the ability to measure this expectation through something called TIP spreads – those government bonds with “inflation-protected” coupons. We can look at the delta between a TIP bond and a regular Treasury of the same maturity and deduce the implied inflation expectation.

So, a fair way (back of a napkin) to look at the 10-year yield sum of parts in a perfect world is:

(1) The fed funds rate (or 90-day T-bill rate) – the RISK-FREE rate, PLUS

(2) Inflation expectations, PLUS

(3) Real growth expectations (give or take) – that is, economic growth beyond inflation.

This third one is important because there is some cost of being separated from one’s money besides the inflationary impact of eroded purchasing power – there is the opportunity cost of being separated from one’s money “while other cool things are happening.” In an economy growing 3-4% net of inflation, a person who lent the government their money for ten years is missing out on all the growth opportunities that come with that 3-4% real economic growth. That has to find a way into the term premium – opportunity cost. And it does. Well, for a long, long time, that hasn’t been at the 3-4% range (since economic growth has been nowhere near there), but some growth expectations belong in the term premium, no doubt.

Now, some astute readers may know that saying a term premium includes inflation expectations (#2 above) and real growth expectations (#3 above) is just another way of saying “nominal GDP growth expectations” – that #2 and #3 combined are called “nominal growth.” And that is 100% correct.

So, is it sufficient to say the proper formula for a 10-year bond yield is the risk-free rate plus expectations of nominal GDP growth? Yes, it is. It works. It’s semantically the same thing. But.

At given points within the 10-year period, one’s expectations of inflation vs. growth may be different, and while the combined data points equal “nominal GDP” expectations and may very well find their way into bond term premiums all the same, the way they affect everything else is profoundly different. If one believes we will get 1% inflation and 4% real growth for ten years, you may very well have a 5% term premium on the 10-year bond; and if one believes you will get 4% inflation for ten years and 1% real growth, you might also get a 5% term premium … But does that anyone think those two different 5% term premiums would be the same thing for the stock market???

Not all 5%’s are created equal.

Right now, the 10-year is almost entirely connected to the risk-free rate – the policy rate is 5% plus change itself, so there is no term premium. But expectations are that the short-term rate will come down, and then varying beliefs about inflation and growth are going to matter – a lot.

But whether you are the Ph.D. bond manager at a fixed-income shop we work with or the lowly investment committee of The Bahnsen Group, you are doing this work with one hand tied behind your back when the yield curve is inverted. Put differently, the portion of bond yields that reflects expectations for the risk-free rate and the portion that is term premium is incredibly opaque. All we can do is speculate. And that is all we could do in our meetings with various money managers – is speculate.

And that is the subject of the speculation – when the Fed will reduce the policy rate so that we can then argue (or wonder) about inflation expectations and growth realities to form new projections for bond yields. Good times.

A general expectation

TIP spreads indicate an inflation expectation of 2% or so over the next decade. That sounds right to me. Expectations for real GDP growth used to be north of 3% for a long, long time. Bond yields came down when real growth came down, period. Chairman Powell said he believes we will get back to 2% real GDP growth. We have been closer to 1.6% for a long time. Therefore, one could argue for a term premium of 3.5-4% out of those nominal GDP expectations in the 10-year. Markets do not really believe the fed funds rate will stay high for years, but the inversion distorts cogent analysis.

What we do know is that right now, bond yields have stayed elevated, adding to stock market volatility, because real growth has outperformed expectations (the recession of 2022 and 2023 that wasn’t) and because the short-term rate is high.

Practically speaking

Where to set duration in a bond portfolio. Where to estimate stock market valuations will go. Where the impact of higher rates will hit the economy. Where this will shake out for real estate. All of these things are directly connected to this discussion of rates – of what the Fed will do, when, and why.

It seems quite reasonable to add a little more duration to bond portfolios, not to a super long duration position (that requires a bearishness about economic growth that is hard even for a Japanification devotee like me), but certainly more than the ultra-short many have favored (for a good reason). If you do not believe inflation will stick to 3-4% for years (I do not), and if you do not believe a world of 3-4% real growth is coming back any time soon (I do not), you can sit somewhere in the middle of the duration curve and be reasonably positioned for both opportunity and risk. Why not ultra short term? Upside risk (capex, productivity, onshoring, industrial opportunity, etc.). Why not ultra-long? Growth expectations do not warrant it – low-term premium. That 4-6% duration seems to make more sense – maybe 7% where you are a tad more optimistic about the economy.

Risk assets out of this bond talk?

That duration conversation may have bored you to tears by now or left you feeling that all we are talking about is interest rates and how they impact stocks. And yes, I expect all stocks – the good ones and the less good ones – will face volatility as rates face volatility and will eventually settle when rates eventually settle. The Fed will not leave us all hanging forever.

But the few managers we did meet with were not hanging on the edge of their seats about what the Fed would do; they still have to get up every day and evaluate companies apart from the volatility of short-term rates. And we certainly have to do the same with our dividend growth portfolio. Our small-cap growth manager, looking only at organic earnings growth and bottom-up company opportunities that fly under the radar, never mentioned interest rates. Our midstream energy manager only mentioned rates in the context of the leverage ratios of our pipeline companies. Their underlying cash flows and expansion opportunities exist outside of the rate discussion. In private markets, the best and brightest all feel that one of two things can happen: (1) Rates come down and boost risk assets, or (2) Rates don’t come down, and a period of distress happens, and they buy good assets at low prices. Either way, that pivot is one they like.

Conclusion

Our Operation Magnify is forever committed to active, proactive, intelligible allocation of capital across Dividend Growth companies, in the Boring Bond space needed to preserve capital, in Credit assets where there is opportunity and compensation for risk taken, in areas of both Growth and Income Enhancement, and of course in Alternatives where we can seek to lower the volatility profile of a portfolio and diversify sources of risk and reward.

Doing that in an era of high rate volatility, of high ambiguity about monetary policy, and a period where far too many eyes are only on the Fed requires a contrarian bend, a deep commitment to real enterprise (bottom-up company realities that transcend monthly price volatility), and a faithful commitment to the principles that made Magnify what it is.

We are blessed to work with the managers we do and to execute in dividend growth as we do. We are blessed to have convictions about portfolio management that are pretty divorced from the volatility of one month’s roller coaster in bond yields.

But we are also burdened with continuing to find the traps that investors fall into and avoid them. We are burdened by wanting to avoid crowded trades yet not being reckless in how idiosyncratic we choose to get.

We believe this entire environment we are in screams for a rigorous commitment to dividend growth, supplemented by careful exposure to private markets. Our credit and bond exposures matter, too, and all investors should be grateful for some bond yield to be back on the table. It brings better optics, transparency, and economic logic to how asset classes are paired.

Now, if we can just un-invert this yield curve, we will really see the forest through the trees. To that end, we work.

Chart of the Week

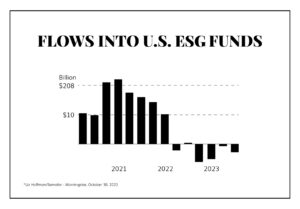

One could argue the peak correlation between investment objectives and virtue-signaling is well in the rearview mirror. But one could also argue – it was always investment-oriented: as long as the politically correct instrument was performing well and the politically incorrect instrument was performing poorly, there was no cost. Once those two things reversed, voila – and we’re all Milton Friedman now!

Quote of the Week

“The magic you are looking for is in the work you are avoiding.”

~ Unknown

* * *

I will leave it there for the week and just say that I have never enjoyed a few days with my team more than I did our annual retreat last week. From our tax department coming off an unbelievably successful first year to the vast resources we have committed to our Investment Solutions and Risk and Planning departments, I am so very excited for what lies ahead. We hope you are, too. No matter when Powell cuts rates.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet