Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

There is no doubt that the primary issue everyone wants me to address is tariffs, and there is no doubt that the President has given us plenty of reasons for me to need to do so. I don’t have to like it, though. But yes, there is a tariff-heavy focus in today’s Dividend Cafe. That said, there are plenty of other issues at play that ended up on my radar this week, too, so this will be an action-packed Dividend Cafe, as it should be.

Markets are experiencing extremely high volatility right now, and I believe the reasons for that are more interesting than the mere fact of market up-and-down movement. So, let’s do another tariff dive, update the lay of the land, and give you the perspective you need to best understand what it all means.

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

Lay of the Land

This is sort of an absurd paragraph to type. The way in which things have moved around over the last few days, a few weeks, etc., around tariff policies and intentions would be unfair to roller coasters to describe as a roller coaster. As of midday Friday, the market was down about 1,800 points from where it was a week ago (the last six trading days saw two huge up days and four huge down days with no low-key days at all). The Dow is down -2,000 points from its recent high (-5%), the S&P is down -7% from its recent high, and the Nasdaq is down -11% … But beyond market movement, the actual underlying tariff messaging and announcements have been an absolute blur of on-again, off-again, delayed, happening, sort of happening, not happening, some will, some won’t, get back to me on April 2, etc.

Rather than a recap of where things have been, what announcements were made, then reversed, then altered, and all of that play-by-play of the last month, here is where we are told things stand now:

- April 2 looms as a day where “reciprocal” tariffs are supposedly coming against all imports (proportionate to the level of tariffs the exporting country charges on U.S. imports)

- 25% tariffs are supposed to go into effect on all Mexican and Canadian imports, but auto imports have now been exempted

- The threatened tariffs against Mexico have, once again, been delayed – this time until April 2 (same date as the above date for “reciprocal tariffs”)

- The products covered in the USMCA pact (“NAFTA 2.0”), which was implemented in the first Trump administration, have been exempted from any new tariffs until April 2. However, other products are supposed to be under the 25% level, except for others that also get exemptions. So you get the idea. In fact, what products fall under USMCA and what products don’t is requiring a cabal of lawyers to sort through (see my point below about the winners of the week), so this additional ambiguity on top of ambiguity may explain why markets didn’t rally on the news of reprieve, and also may explain why felt costs will be muted (the non-impact of non-tariffs remains a tough way to analyze tariffs).

- If, indeed, April 2 “reciprocal tariffs” happen, the line items of products would go from 15,000 (seems like a lot to me) to 3.1 million (seems laughable to me).

- One other point: the administration has said European VATs will be considered a tariff when we consider our reciprocity, but the VAT rates are all different country by country and product by product, and all have exemptions and credits associated that push the effective rate way, way down in many cases. Calculating a VAT rate to use when calculating a reciprocal tariff rate to use is, ummmm, not going to be easy

A basic ideological question: Let’s say these tariffs are to help American workers, grow revenues for the U.S., and benefit the economy, all claims I emphatically dispute, but let’s just presuppose it for a moment … wouldn’t that rather clearly imply that exceptions and exemptions hurt American workers, hurt revenue for the U.S., and hurt the economy? In other words, if the tariff ideas are all roses, why would we want or need exceptions and exemptions? Bigger is better, yes? I think this question answers itself, and I am not trolling in bringing it up but making an economic point: No one actually believes what is being said, and actions prove that I am right here.

What we see right now that seems undeniable in the President’s own actions, statements from Commerce Secretary Lutnick, and the way this whole deal is unfolding is that some sectors are going to be exempted, and then other ones will not (until some evidence of pain is seen). Put differently, there is nothing universal about any of this – it is about to be the most discretionary deployment of tariffs imaginable. Discretion all at once promotes cronyism and favoritism (see below), but it also mutes economic impact, and fosters an even higher uncertainty about what to expect.

Where things stand now: More tariffs have been announced. More tariffs have even been implemented (sort of). And the ideological rhetoric has been ramped up well past the “we want your help at the border” level to a more explicitly protectionist rationale. And markets have responded.

The not-so Inside Baseball

Kevin Hassett is the head of the National Economic Council (NEC) for this Trump 2.0 administration and was the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) in the Trump 1.0 administration. He has the job now that our own advisor, Larry Kudlow, had in the first term. He wrote a book called The Drift after Trump’s first term and before his recent election in where he described the policy divide in the first administration – one camp of rabid protectionists who sometimes had the President’s ear (Navarro, Lighthizer), versus another camp of traditional conservative supply-siders (Hassett, Kudlow, Mnuchin). He describes it as “one group that wanted to drive versus our group that kept them from driving us into a ditch.”

It is not a big secret that there is still a divide on this subject within President Trump’s economic advisory team and inside his own brain. Kevin Hassett and Secretary Bessent have spoken of the efficacy of tariffs for negotiation yet have maintained that the ideal ending place is fewer tariffs, not more. Their lives and careers have been consistent with the tenets of classical economics. Conversely, the more nationalistic and protectionist camp – Jamieson Greer, Stephen Miller, Peter Navarro, and apparently (sometimes), Commerce Secretary, Howard Lutnick – represent a competing ideology. I would argue that in Trump 1.0, Vice President Pence was on the Hassett/Kudlow/Laffer side, and in Trump 2.0, Vice President Vance (who is far more empowered than Pence was) is on the Miller/Navarro side (to a large degree). None of these things align perfectly and there are nuances and differentials, but I think these descriptions work for broad purposes.

Six weeks into the new administration, I think the wrong camp is winning the internal conversations, whereas in Trump 1.0, the right camp won. I would not say this is dispositive or final, but I would say it is significant. Yet, at the end of the day, the decision made between the ears of President Trump will be the deciding factor, not the persuasive abilities of Camp 1 or Camp 2.

The Bond Market Speaks

The 10-year bond yield was 4.4% after the election. It was 4.8% on January 14, the highest it has been since 2007, besides a couple of days in October of 2023 when it hit 5% for just a minute. As of press time today, it is 4.27%, having hit 4.15% earlier this week.

10-year inflation expectations (essentially, the spread between the 10-year yield and the 10-year TIP security) were 2.27% after the election. They went to 2.44% when the 10-year was at its peak on January 14 and sit at 2.34% now (as of press time).

So, if you view the 10-year as a proxy for nominal GDP growth expectations (it is), and you take the 4.4% yield after the election less inflation expectations of 2.27%, you get 2.1% as the REAL GDP growth expectations after the election. At the point, the 10-year was 4.8% six weeks ago, and inflation expectations were 2.44%, REAL growth expectations were 2.36% at the inauguration – in other words, REAL growth expectations went up MORE than any move in inflation expectations after the election, up until the inauguration. And now, with a 4.27% bond yield and 2.34% TIP spread, you have a 1.93% real growth implication, the lowest in quite some time.

The inflation expectation was around 2.3% after the election, and is around 2.3% now. What has caused bond yields to drop is REAL GROWTH EXPECTATIONS, which have dropped by almost half a percentage point since the inauguration!!! My friends, this is because financial markets see tax reform as being de-prioritized, or at least financial markets are worried about its prospects, and because more than inflationary concerns over a trade war, the bond market sees a trade war as anti-growth.

What am I Really Concerned About?

Do I believe that President Trump will end up provoking a full-blown global trade war? I do not. I do believe he has said things and will continue to, that if consistently executed would indeed create such (i.e., “tariffs will make us rich,” “we are getting ripped off when countries sell us more than they buy from us”) – but I ultimately believe two things, neither one of which are an endorsement of the approach (which I have repeatedly criticized):

- His primary objective in tariffs is a “deal”—whether it is with Canada, Mexico, China, India, or Japan. He likes “deals”—some that may be substantive and some that may be totally cosmetic—but he likes deals. And while I fully acknowledge they are both articulating and, in some cases, doing things around trade and tariff policy that transcend mere dealmaking/negotiation, I continue to believe that this is the ultimate end.

- To the extent I am wrong on #1, I believe markets will humble the policy idea and force a significant reversal of intent, thereby averting a full-blown trade war.

Will there be all kinds of moments where a belief in this version of an end-destination is called into question? Sure. That was part of my prediction to begin with, and in fact it has already happened multiple times in the last five weeks! But the far left tail risk is, I believe, going to be avoided because of point #1 above, and if not that, point #2.

But that does not mean all is well. This is not a benign version of circumstances.

If we are headed to a currency deal with China, or a border deal with Mexico, or better tariff rates with other countries, or all of the above, it will not change the fact that along the way there is going to be an uncertainty risk premia in markets that heightens volatility, and more importantly there will be a delay or suspension of economic activity that hampers productivity. Uncertainty is not only an issue in asset prices; it impacts economic activity – and in an economy with as much “mixed bag” data as this one, I simply believe it is playing with fire.

The Most Recession-Proof Industry Ever

It was a very good week for lobbyists, which was entirely predictable. One of my biggest criticisms of tariffs (and any other form of taxation that is ripe for exceptions, exemptions, carve-outs, and favors – that exists outside of broad-based equal treatment under the law) is their inherent plea for opt out. Tariffs are supposedly needed for the protection of workers (well, some workers), yet they allow for exceptions for the auto sector, energy products, or whoever else has the connections to get exceptions (I have written before of my intimate knowledge of the massive carve-outs given in 2018). As opposed to tariffs, I am happy to see Sector A or Sector B get relief from tariffs, but the problem is that I want Sector A and Sector B to get relief because I want the whole alphabet of sectors to get relief. Tariffs attract cronyism, and cronyism is the driving force of the lobbyist industry. They had a good week.

Currency Connection

The Peso is down 8% to the dollar as all of this has unfolded. If you are not traveling to Mexico, why do you care? U.S. companies that export to Mexico have an 8% less competitive (more expensive) product to sell. A weaker currency loosely protects the country whose products are being taxed when we import them (the exchange rate benefit offsets the cost of the tariff), shifting the impact (to some degree) from the importers who are allegedly being punished to the exporters who were allegedly being protected. This doesn’t work perfectly but it is a natural, organic, and perfectly rational chain of events …

I have believed for some time that Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, a global macro trader by career and one who has publicly written about the need for a new currency accord with China, believes currency will be an off ramp in the ongoing broader dispute with China. Japan’s deep regrets over how the Plaza Accord of 1986 went will certainly inform how China approaches such a measure in 2025. Still, the notion of a currency agreement wherein the dollar depreciates relative to the Yuan is not just possible out of all this, but I would argue that it is probable. Currency appreciation is more tolerable for China than tariffs, and some domestic demand focus is perfectly consistent with Chinese policymaker’s agenda.

The fact of the matter is that trade and tariffs get all the headlines, and both create visible and measurable data points, whereas currency exchange feels invisible and is harder to measure in many ways. If the President’s agenda is more competitiveness for American manufacturers, he is far more likely to see that happen with some modest and controlled dollar depreciation (and agreed upon Yuan appreciation) than he is tariffs – and with a lot less collateral damage. And because currency markets are like any other financial market – they play out whether we try to make them do so or not – the real question is whether or not they make this happen intentionally or by default.

The Boy and the Wolf and the Market

There have been about three times in the last five weeks where markets were told big tariffs were coming, markets dropped, markets were then told the tariffs were not coming, and markets rallied. On Thursday, March 6, yet another suspension of previously-announced tariffs was announced, but markets sold off (as of press time, this has continued further into Friday). Was the market saying, “we are tired of the on-again, off-again announcements and at this point we are responding to the uncertainty, not with the zigs and zags of what gets said” … OR … was the market saying, “great, the tariffs may not be happening, now, but you know what, we don’t see a tax bill coming that meets expectations, and we see other economic data that concerns us – jobs, GDP, ISM – so we are just going to go ahead and sell off anyways.”

Of course, Mr. Market doesn’t actually talk, but you get the idea. I am convinced that if Mr. Market did talk (the combined personification of stock and bond markets), he would be saying one of those two things—and maybe both.

A -7% drop in the S&P 500 is not a real drop. It is nothing. It is irrelevant. It happens every single year (okay, there have been two years in my adult life where it didn’t). Is it predictive of a further drop? I haven’t the foggiest idea. My only point is that it is very clear we are in at least a temporary period of heightened volatility with markets lacking clarity on at least two key policy issues and maybe more economic matters.

Does it matter? That has been addressed.

Making International Investing Matter Again?

An interesting development in the first six weeks of the new administration is how international markets have fared better than U.S. markets. Now, it has been just a few weeks, and of course we are talking about a long, long, long time where U.S. markets have trumped international markets. However, there are a handful of issues that provoke the question as to whether or not the market premium the U.S. has enjoyed relative to international markets will last. U.S. nominal GDP growth, which was weak compared to its historical record, was stronger than that of its international counterparts post-financial crisis. If there is some reversion in historical valuation relationships, and if other countries prove more capable of competing and attracting foreign capital, it would be a fascinating development, indeed.

Conclusion

Several analysts I admire to the ends of the earth believe we are in the early innings of a total unraveling of the trade regime the world has functioned in for over thirty years. A few people even believe that will prove to be a good thing. Others believe there will be some changes but not an unraveling, and others believe there will be “announcements of changes” but not any unraveling (or even substantive changes).

I offer no opinion on where exactly this will go, though I have plenty of opinions as to where it should go. What I do believe is that the downward pressure on growth, whether from uncertainty or actuality around trade policy, makes the stakes for supply-side tax change all the more significant.

I could write a full Dividend Cafe on what a more interventionist industrial policy would mean for investors and the implications of using trade policy to effect capital distribution. I certainly could devote a Dividend Cafe to more remedial economics around why a trade deficit is common for a large country in a position to buy a lot from others and how supply-side endeavors make us more productive. And I devote plenty of my time already to defending capital markets as vehicles for productive activity, not merely “moving money around” – as some recklessly suggest.

But where we are now is not the old regime or yet a new regime, but rather a moment of uncertainty. And in moments of uncertainty, markets panic, bad investors join the panic, and smart investors assess with sobriety and patient judgment. And when that uncertainty is connected to the decision-making process of this particular President, for good or for bad, it is an especially bad time to have high conviction about exactly what will play out. The lens through which I view all of this has been laid out in this commentary. And much will move and shake on the way to some resolution. But we will hold the ship steady along the way, humble, nimble, and driven by the required discipline. To that end, we work.

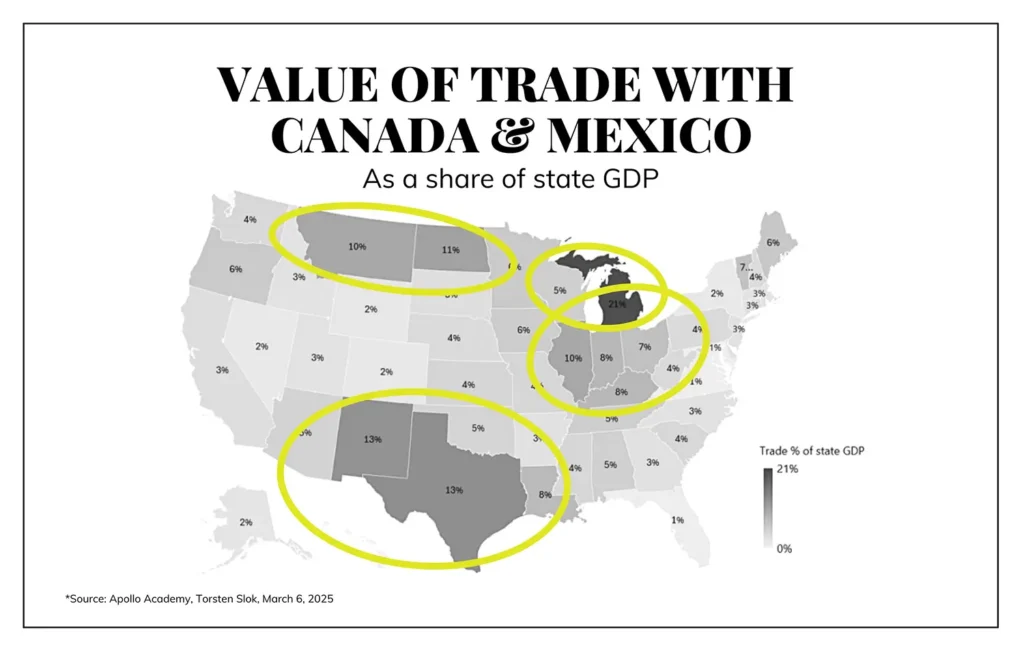

Chart of the Week

The states where imports and exports with Mexico and Canada make up the highest percentage of GDP are shown below. It is not too hard to see why even those who claim to love tariffs might want to exclude the auto sector!

Quote of the Week

“Humankind cannot bear very much reality.”

~ T.S. Eliot

* * *

I will be in our Palm Beach, Florida, office the second half of next week, visiting our team and seeing quite a few clients Thursday night. That office has grown immensely since we opened it, and Joleen and I are excited to be there. I enter this weekend without a clear plan for what Dividend Cafe will be about next week. My prediction? It will not be about tariffs but will have the word “tariff” in it.

Have a wonderful weekend!

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet