Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Tell me what you think about these two statements:

(1) Markets are dynamic, ever-changing forces. They are never predictable, their outcomes are never assured, the inputs are constantly adjusting with the ebbs and flows of different circumstances and facts that have to be monitored, studied, and adjusted as needed.

(2) There is nothing new under the sun.

I believe these two statements are both true, and I believe that the apparent contradiction between the two actually represents one of the great challenges and obligations for professional investment managers. And that is the subject of today’s Dividend Cafe.

We live in interesting times. We live in unpredictable times. And we live in times that offer a milieu of circumstances which combine the novel with the redundant. And for all of the uncertainty about the future and the debate in the present, there does exist a past that can, at a bare minimum, help inform us in the present and in our preparations for the future.

The “new” must be informed by the “old.” And that is what we are going to discuss in the Dividend Cafe today.

Knowledge of the Past

John Kennedy once said that a knowledge of the past prepares us for the crisis of the present and the challenge of the future. It is my contention that the more things in the present we believe warrant analysis, adjudication, decision, monitoring, moderation, adjustment, concern, questioning, curiosity, etc., the more we need a robust understanding of history, of past events, past cycles, past lessons, and even past differences that may seem to offer no direct lesson, but may in fact have much to offer.

Crisis of the Present

What do I mean about the present set of circumstances? On a daily basis we face questions about the economy, about the durability of economic growth, about the impact of potential tax changes, about America’s economic supremacy, about the role of the Fed in our economy, about populist uprisings (right and left) and their influence on public affairs, about the level of national debt, about valuations in the market, about new innovations and technologies, about the creative destruction some technologies are spurring, about the societal and political response to the size and power of big tech companies, about our relationship with Communist China and its growing hegemony, about a new role for the state in the administration of the economy, about the affordability of sovereign debt all over the world, about the social fabric of the country in a time of intensifying polarization, and about any number of a dozen or more other things you could list as “present” concerns – crises, if you will.

It is ironic, though. We have never been richer. National income has never been higher. National wealth has never been larger. Medical technologies have never been better. Vaccines have never come quicker. Transportation has never been more convenient. Quality of life has never been higher. Access to food has never been more prevalent. The daily amenities of life have never been more spectacular. All of these things are true.

And yet everything in the preceding paragraph is true, too. We feel a swarm of current crises even as we have more resources and margin with which to process them all.

Challenge of the Future

And of course, the crises of the present I refer to may or may not warrant a current, daily remedy – but what really gives us angst is not just how today will play out, but how tomorrow will play out. And for those who have the character to care about something beyond their own daily satisfactions, we justifiably wonder what the future will present to our children and grandchildren. Some of us may even care beyond the generations we know or immediately imagine – but may care for the long-term future of our nation, and indeed our civilization.

The debt “crisis” has long been thought of as a current event, when it has always been a future one. We have just never been able to pinpoint how “future” the future is. But when we talk about the sustainability of our entitlement programs, the solvency of our nation’s finances, our relationship with China, and so many of the items listed above, we really do have a “future” challenge in mind.

The Bay of Pigs was a current crisis (when it was happening).

The Cold War was a future (long-term) reckoning.

Both worked out. But the present and the future have a way of blending together in our minds. Then, when what should be “future” challenges do not end up being “present” crises, we can grow numb or apathetic and dismiss the legitimacy of the future challenge. Out of sight, out of mind.

History as our guide

I do believe the Solomonic wisdom that “there is nothing new under the sun.” For one thing, I don’t really have a choice but to believe it – some of you know why – but regardless, there is not a painful tension for me here. The reason is quite simple – the idea that there is nothing new under the sun does not mean that the Fed will not ever buy direct ownership in junk bond ETF’s, even though they had never before done such. They did do so – in spring 2020 – and it had never been done before, and it has profound implications for our credit markets which will be with us for many years.

But the Fed had become a savior of capital markets for many years. Its interventions had exceeded the plain reading of its dual mandate (sound money and full employment) for a long time. Other nation’s central banks had taken creative and aggressive actions with their balance sheets that met or even exceeded that the Fed ended up doing in this isolated case.

In other words, this was a new application of a very old reality.

I only use the Fed’s intervention into junk bonds as a very random example. You will not find anything in my list or your list that does not represent either a repeated application of a old reality, or a new application of an old reality. But in all cases, no matter how challenging or complex the newness of application is, the Solomonic wisdom applies.

There is nothing new under the sun.

In history, we have lessons to help guide us understand what has happened, why it is happening, and what various options we might want to consider to navigate through.

The complexity of the present challenges often will not allow a perfect parallel to past events. The cliche about history not repeating but rhyming is useful, here. And none of this means this will be easy. I simply mean that the idea of engaging present crises without any engagement of the past is suicide. We are better empowered when we have learned from past lessons, and sought the wisdom necessary to apply these lessons to current predicaments.

Meat on the bone

In late 2012, President Obama was rather easily re-elected in his race against Mitt Romney. This meant that the Bush tax cuts would expire in about six weeks, and a Democrat President who had a Democrat majority in the Senate would be in charge as the tax cuts of ~10 years earlier sunset away. There would be no vote required in the House or the Senate for taxes to go higher, and the newly elected (popular) President wanted higher taxes.

The wave of planning that took place over the next six weeks was a bonanza for lawyers, insurance companies, accountants, and investment consultants like I have never seen. People knew capital gain taxes were going higher so they began selling assets, restructuring assets, preparing for loss offsets, gifting, and any other number of activities necessary to mitigate the impact of the inevitable. People knew estate taxes were going higher – a LOT higher – so they set up new trusts, gifted assets, froze assets, did DGT’s, GRAT’s, CRUT’s, ILIT’s, and any other alphabet soup they could to prepare for the inevitable.

Then, the present happened. And like the past, it turned out that politicians talk about the estate tax a lot more than they raise it. And like the past (Kennedy, Reagan, Clinton), it turned out they were a little less eager to starve capital formation than they may have let on.

The capital gain tax did not explode higher, the reduced rate was made permanent. The estate tax did not explode higher, it was actually reduced, a lot (40% rate vs. prior 55% rate), and made to apply to a lot less people ($5mm net worth single, $10mm married – vs. the prior $1mm exclusion).

Now, does history assure me that capital gain taxes and estate taxes cannot and will not ever go up again? Of course not.

But the lesson of the past here to prepare for the challenge of the future is to not do expensive and sacrificial planning and maneuvering based on speculation. Conjecture is often wrong. The cost-benefits calculus favors patience – not shooting from the hip.

Speaking of Kennedy

Speaking of things John Kennedy said, he also once said: “The tax on capital gains affects investment decisions, the mobility and flow of risk capital … the ease or difficulty experienced by new ventures in obtaining capital, and thereby the strength and potential for growth in the economy.”

What can I say? I’m in a JFK-quoting mood today …

The past doesn’t change but the future past does

I think my headline above says what I meant it to say but I just re-read it three times and now my head hurts. The events of the present (which in the future will be the past) are different than the events of the past. What happened, happened, but what happens, well, that will be different (or could be different). The simplest way in the world to deal with this conundrum is to absorb everything one can out of the past, extract all lessons, information, and material, and seek with experience and wisdom to apply those extractions to what we know of the present.

Applying one lesson learned to another

Consider the following:

- Interest rates in Germany in 1994 were at generational highs, and the UK sterling pound was down 20% in less than two years having left the exchange rate mechanism. Policymakers feared that Europe would never be able to adequately tighten monetary policy if such became necessary. Here we are in 2021. The German bund pays a NEGATIVE 0.2% yield. Europe’s central bank has added trillions to its balance sheet. Rates are at zero. The issue now isn’t that Europe doesn’t have room to tighten; they don’t have room to ease. The issue now is that the pain of tightening is worse than the pain of not tightening.

- At that same time, Japan was in the early innings of his violent debt-deflationary violent implosion.

- And at that same time, Greenspan and the Fed were raising rates in the U.S. The bond market revolted. Orange County, California went bankrupt. But the U.S. and its currency became irresistible to the rest of the world. Europe was stuck. Japan was stuck. The U.S. was not – rates went higher; the currency rallied, and it rallied hard.

What is the point I am making here?

Each country/region in the aforementioned history less has different circumstances now. Who can tighten and who can not and why is all different – across the globe. But if I don’t learn from these situations in the past to see what it may mean for the future, I am not doing my job.

The economies that have options with their monetary policy have a lot of leverage over economies that do not. I’ll talk in future Dividend Cafes about who has that leverage now (hint: it’s not us). But as we talk about present conditions with currency, interest rates, debt, economic growth, and trade – we may have different actors in different roles now (and we do) – but perhaps much of the play is still the same.

“Unprecedented”

There are a lot of things happening in the world that are unprecedented. $6 trillion of proposed spending packages (COVID, infrastructure, Families Act) in a four month period is unprecedented.

Negative interest rate bonds totaling over $10 trillion.

Central bank balance sheets skyrocketing to multi-trillion dollar levels, everywhere.

I could go on and on, and all of the things I mention would be “unprecedented” in one sense, and totally precedented in another.

We now have ample precedent for the governing belief – the philosophical north star – that the central bank’s job is to facilitate government expenditures, and to avoid damage to financial markets. The coddling of risk assets is not new; it just leads to new extensions of that belief. We have ample precedent for people that demand more from their governments (spending, benefits, transfer payments, etc.) getting it through borrowed money.

We have ample precedent for the thing that creates the borrowing (more wealth redistribution) taking away the thing that could help pay the borrowing back (less wealth creation). This is not new.

The way in which these things play out will be “unprecedented.” The driving belief systems and economic laws that sit at the foundation of all this are not.

Deciphering the very best we can from the past to apply those lessons to the challenges of the future: To that end, we work.

Chart of the Week

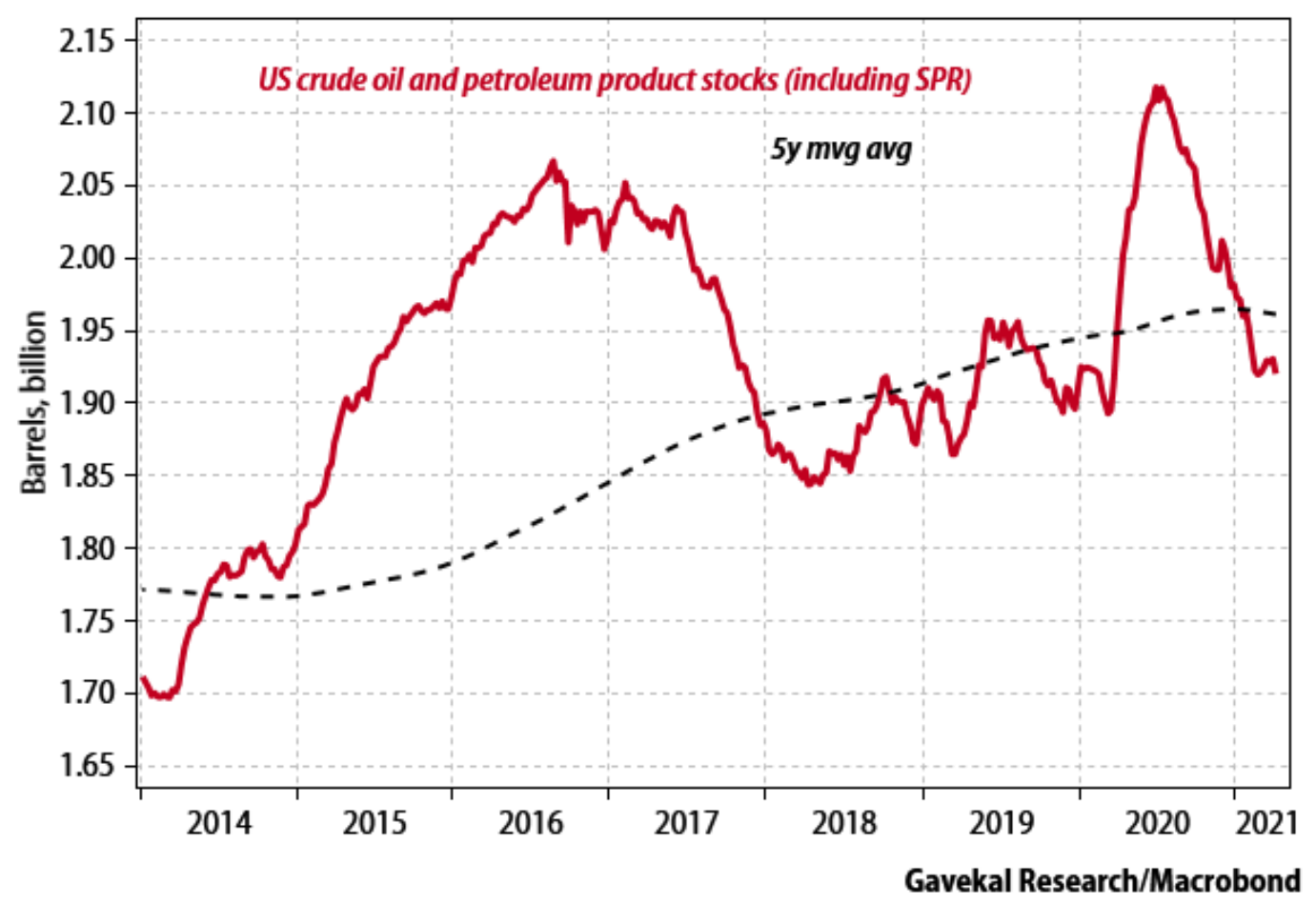

Remember when world oil supply was so high we couldn’t find a place to store it a year ago? Stockpiles are now back to pre-pandemic levels – the by-product of curtailed production last year and growing demand this year. It helps to learn from history when understanding laws of supply and demand. In this case, the lessons are a few thousand years old.

Quote of the Week

“Being captive to quarterly earnings isn’t consistent with long-term value creation. This pressure and the short term focus of equity markets make it difficult for a public company to invest for long-term success, and tend to force company leaders to sacrifice long-term results to protect current earnings.”

~ Charles Koch

* * *

The quote of the week may not have applied to the subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe much, but it applies to earnings season a lot, so I thought it worth sharing as we navigate through this one.

Reach out as always with any questions or comments, and have a wonderful weekend. The month of April has come to an end. I love the month of May.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet