Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Market volatility has picked up. The election cycle is positively crazy. Earnings season is underway. And with all of that current affairs landscape at play, I have decided to use this week’s Dividend Cafe to …

… ignore all of it entirely.

We need to look at inflation this week, but not the “next CPI report” or the timing of the current Fed target. Rather, we need to look at structural inflation and consider some arguments for upside inflation risk that go beyond the short-sighted views of the last few years that ignored history and reality. It is a robust discussion that you will want to read, scout’s honor!

And beyond the inflation conundrum, there are a handful of other nuggets, from growth vs. value to REITs to IPOs to a flaw in our thinking about government debt. This is what a weekend is for! Jump on in, to the Dividend Cafe!

|

Subscribe on |

The Inflation Conundrum

You may have heard of several schools of thought about inflation. Differing opinions on what generally causes inflation, differing opinions on what caused the 2022 inflation, and differing opinions on what to expect from inflation going forward leave ample opportunities for a mixed bag of perspectives.

One school of thought that I have [by necessity] tirelessly disputed for a long time is the belief that excessive government spending and easy monetary policy is, necessarily, inflationary. This is not because I support excessive government spending and distortive monetary policy but rather because I oppose excessive government spending and distortive monetary policy. The school of thought that has believed this has unintentionally proclaimed that the government can “heat up the economy” with levers they firmly control and “cool it down” by moving those same levers the other way. Sorry, but this is not true, and it has never been, and the testimony of history is abundantly clear (see: Japan, United States, EU, UK). My Japanification thesis runs counter to the view that all fiscal and monetary thesis is inflationary, though I certainly concur that policymakers wish it were!

But what about a school of thought that does believe the forward risk is to upside inflation but does not believe the reason is the glut of spending and money creation that defined 2020-2022? The historical fact of global deflationary bias from 1980-2020 is not up for debate, so why would there now be a global inflationary bias if the debt and monetary interventions of the prior forty years created a different outcome?

First caveat: this is not my view. I am capturing the view of others, not stating my own. I do not believe people will look back in ten years and say, “Wow, nominal GDP growth sure was hot this last decade!” But those who see the 1920-2020 period the same way I do (that is, those with ears to hear and eyes to see) may still have a different view of the future than I do, even outside the conventional view about fiscal and monetary policy (the one I vehemently reject). Using the outline of Anatole Kaletsky, a respected Keynesian economist, the factors that this school of thought believes will drive upside inflation in the years to come are:

- Deglobalization – less competition globally means less downward price pressure

- Demographics – more baby boomer retirees mean more government spending and less immigration means fewer workers to fund retiree expenses.

- Politics – populism demands higher wages for middle-class earners, which creates an upside wage-price spiral

- War-increased defense spending drives deficits higher, and “everyone knows” war spending is inflationary.

- Environmentalism – global opposition to fossil will limit supply even as demand continues; at the same time, an energy transition to renewables will require high capital intensity

- Technology – the Mag 7/FAANG type names are monopolistic and have unlimited pricing power. AI efficiencies are overrated, and the risk is a higher cost of technology, not a lower one, in the future.

If you believe all of these things or at least 3+ of them, you can see where some view of nominal GDP expansion fueled by inflationary pressures was possible and even probably.

I happen to not believe any of them, like a single one.

I do not believe deglobalization has to be inherently inflationary. For one thing, the pace of deglobalization is still highly uncertain. However, it is entirely possible that the increase in cost at deglobalization is spread out and temporal and offset by greater productivity in regionalization and other marginal efficiencies that create an entirely different price outcome.

Declining demographics are inherently deflationary, at least in modern economies that have experienced such. Aggregate demand declines, innovation falters, the dependency ratio skyrockets, and more resources come from the productive to the unproductive as a percentage of output in the economy. Again, this category seems like an odd controversy given what we have empirically observed in Japan for over three decades.

I wholeheartedly agree that populist politics drives more redistribution, but I dispute that this is inflationary. Poor allocation of resources puts downward pressure on nominal growth. I agree that protectionism is inflationary, and I agree that many have decided to pretend protectionism sounds like a good idea. I do not agree this bad idea can or will last.

I suppose it is easier to debate if we are entering an entirely new paradigm regarding war than it is to debate whether or not war is inflationary. I confess that I don’t find the argument that “everyone knows war is inflationary” to be persuasive, but I would push back on the idea that we are in for a new era of war. I believe we just live in an era of global instability (from Genesis 3 through the second coming), and I would not take it as a given that defense spending as a % of GDP is headed higher (I wish it would, with an accompanying decline in non-defense spending as a % of GDP). And even if it is, I do not believe that points to clarity about inflation vs. deflation, either way.

The environmentalism argument is intriguing. Will zealots get their way and put downward pressure on fossil production even as demand stays level or even grows higher? What is interesting is that this is (a) Not an argument for a broader increase in the price level but rather a specific increase in a specific spending category, and (b) It presupposes that the side that is currently on their back foot will win. Is ESG more popular now than it was four or five years ago? Hardly. Regardless, oil was $10-20 in the 1990s and went to $100, and now has a ~$60 floor with $70-100 range considered a given. And yet this multi-decade period of rising energy costs was accompanied by some of the lowest inflation rates in history.

The technology argument is intriguing to me. That the big tech companies have monopolistic pricing power in practice (even if not legally, which is a huge difference I insist on making) is certainly true, but I ask you, has Amazon made your purchases more expensive or less so? And besides, how does one square the politics point with the big tech pricing point? If we are to believe populist rage is going to drive more redistribution, should we not also assume it will drive a breakup of big tech? Look, I am reasonably AI-skeptical about coming efficiencies, but none? Is no price efficiency coming? No increase in margins? I just don’t believe it. Technology has been significantly deflationary for decades, and I can’t fathom why that would change directionally. The pace and magnitude of the impact may change, but not the direction.

This time is different – the bond version

Those who believe the risk in inflation is upside risk (and dramatic upside risk, at that) have always had a really inconvenient problem to deal with – the big, bad bond market. Nominal long-term yields of around 4% in a 2% real GDP growth environment point to something like 2% inflation, not 4-6%. How do they explain this away?

Well, the bond market is wrong, of course. Asset allocators around the globe responsible for trillions of dollars are painfully over-exposed to duration risk, according to this school of thought, and it will soon end in tears. It is not low/moderate yields that are structural but rather rising inflation that is structural, according to this school of thought. Therefore, the bond market is not doing its job at price discovery.

This time is different, eh? Well, maybe. Humility is important in this line of work. But my advice for readers is to have a very, very high burden of proof and conviction before you bet against the bond market.

********

A few other odds and ends …

Reason #72 Higher Rates Didn’t Break the Market

Look, down near the “zero-bound” of the fed funds rate, from 2015 through 2022, interest expense across the S&P 500 averaged a stunningly low 3.5% across aggregate S&P 500 corporate debt, and it is true that over the last year of higher rates, the average interest expense divided by total S&P debt has gotten up to a whopping 4.1%. But that number was between 5% and 7% for decades before that, meaning, even in this higher rate environment, the average borrowing cost as a % of debt remains well below average and quite accommodating to total margins.

Not even a broken window of productivity

Simply put, a key cornerstone of Keynesian thinking is that government spending can stimulate the economy (fiscal policy), as the spending goes to various things that otherwise wouldn’t be happening that create economic activity (for example, New Deal programs, building factories, ordering planes or missiles from defense companies, infrastructure projects, etc.). Without even getting into the debate over whether or not this kind of spending is a way to stimulate the economy (i.e., what resources it diverts from in the present or the future), we can at least acknowledge that this kind of deficit spending is what Keynes had in mind.

But not all $2 trillion deficits are created equal. If the U.S. government spent $475 billion on interest in 2022, but $600 billion in 2023, but $900 billion in 2024, that is $300bn year-over-year and over $400 billion in two years where the total deficit spending has not gone up or down, and yet the amount going to theoretical Keynesian stimulative purposes actually went down.

It is the worst of all worlds. More debt for the future to contend with. More bonds were issued. More capital is diverted from productive investment to funding the government. Yet without even the Keynesian concept of productive stimulus to show for it, as dubious and incomplete as even that project may be.

If your kid wants to take an advance on the credit card to buy a guitar and chase his dreams, it may be a bad idea, but at least there’s a little hope behind it. If he wants to take an advance to then set the money on fire, well, that becomes an easier call, I imagine. Frederic Bastiat’s broken window fallacy in 1850 talked about believing it was good for the economy for a shopkeeper to have to spend money on repairing the glass a hooligan broke by throwing a brick through his window, all the while ignoring what the shopkeeper would have spent that money on. With 2024 government spending, we should be so lucky as to have windows to repair!

The Growth/Value History

If you started the 1990s with an even amount of growth and value in an equity portfolio, by the end of the decade, your growth was worth 73% more than your value. If you waited until the end of the next decade, ALL of that growth premium went away (it actually did it in ONE year!), and now there your growth was worth 27% LESS than your value! From +73 to -27 … Well, over the last ten years, going into July, the growth over value (starting off equal weighted) is more than double.

But you know what they say, “Past performance is not indicative of future results.” Uh huh.

You thought you had it bad!

Publicly traded REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) in the United States were down -1.9% in the first half of the year. While the strong last ten weeks of 2023 caused them to be up +13% last year, they had been down -25% in the bad year of 2022. Bottom line: it has been a rough three years for publicly traded REITs (in aggregate) in the U.S., after a huge +43% year in 2021.

But have you seen the China REIT numbers? Holy moly. Down -13% so far this year. Okay, not good, but not life-threatening. But that is after being down -35% last year. Ouch. Oh, and -23% the year before that, and -25% the year before that, and -15% the year before that … The five-year REIT CAGR in China is -23% per year (five years in a row).

It’s not beyond bad, but it’s pretty stunning. What causes something like this to happen? Intense over-valuation.

From froth to not froth

There were 180 IPO filings in 2021 (that was the peak of the SPAC moment, and it should be said that not all of these filings resulted in a completed IPO). There have been about thirty filings so far this year. An 80% reduction of IPOs in a screaming bull market that has made 39 new highs this year is not normal. But, either was 2021.

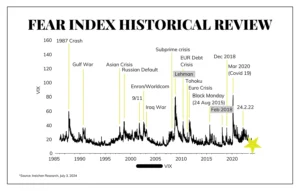

Chart of the Week

The “fear index” has priced many dramatic events over the years—Lehman, Enron, 9/11, COVID, etc. Right now, it is as low as it goes. Complacency? Maybe. But market actors who are also not buying the doom and gloom of the day? That, too.

Quote of the Week

“I have observed that not the man who hopes when others despair, but the man who despairs when others hope, is admired by a large class of persons as a sage.”

~ John Stuart Mill

* * *

We have a couple of new people starting in our Phoenix office next week, four other new people starting in other offices the week after that, our long-awaited Florida office opening next week, and some other big announcements coming (one of them being one of the most significant client value-added offerings we have ever concocted). It’s a #fulltime gig here at TBG, and we remain earnestly devoted to our clients. To that end, we work.

Reach out with any questions at any time.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet