Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I hope you all had a wonderful Fourth of July holiday. I love Independence Day, and I love celebrating America’s independence. I love the Declaration of Independence (and I should add it has quite a bit of economic messaging in it). And of course, having the time to celebrate summer, family, friends, and all the traditions and customs that go with the Fourth of July is time well spent.

I devote this week’s Dividend Cafe to your questions for us – the top questions and inquiries that have hit our inbox over the last week or so. The topics cover the whole gamut this week, and I think you will find it fruitful and edifying.

So jump on into the Dividend Cafe, and let’s answer your questions!

|

Subscribe on |

Economics 101

“I have heard that further rate hikes end up pouring more fiscal deficits into the economy by raising the Treasury’s average interest expense, which is ironically stimulatory to a certain degree. Does the rate raising by the Fed have a short-term stimulatory effect on the economy?”

I believe that all Keynesianism is deeply flawed in its underlying philosophical tenets, but this statement is one that I am pretty sure would make John Maynard Keynes himself spin in his grave. How in the world higher government spending on interest expense could be stimulatory is simply beyond my capacity for imagination. Those who believe deficits stimulate the economy generally say so because of what is causing the deficits – i.e., spending on some government project that hires people, or tax cuts that lead to more productive activity, etc. Even those theories require some sense of economic worldview (what activity is not receiving resources because of the spending being done elsewhere, etc.) – but at least there is a prima facie case for some activity creating the budget deficit. The idea that higher interest expense is stimulative is categorically false, and in fact, to the extent that it doesn’t even lead to curtailed behavior (i.e. “hey, maybe we should spend less money since the cost of borrowing has gone up”) it is nothing more than setting money on fire. Those who see economic value in the government paying the Fed more money to borrow more money are in desperate need of an economics primer.

Bitcoin, again

“With all the buzz lately about cryptocurrency ETF’s from Blackrock, etc, are you planning to weigh in on this latest shiny object? I have zero interest investing in this, but my kids are talking about it. I’m not well-versed enough to explain why this is a very bad investment opportunity so I just sound like a ‘boomer’ dad telling them no.”

At the end of the day, all this question really addresses is whether or not one should own Bitcoin. An ETF that may or may not come out from an asset manager (the SEC has previously denied all applicants but seems to be moving along with more recent applications for such), but assuming it is constructed as intended, which I have no reason to believe it will not be, it would more or less be a proxy for how bitcoin’s price performs. So really the question is, “Should I own bitcoin?”

And with that question, I yet again get to answer with a few questions. What is it that would make Bitcoin go sustainably higher? There is no yield or coupon, and there is no earnings growth, so without an internal rate of return, a Bitcoin bull bases their bullishness on what, exactly? Speculation? Okay, I am against that. Confidence that more people will want to pay more for it? Okay, but why? A view that its low supply guarantees its price appreciation? I don’t think that makes any sense. A view that it will be a substitute currency? I reject that view out of hand (so should you).

At the end of the day, we are left with speculation. And that means it may go higher. And it may go lower. And the volatility around it has been monumental. And the lack of understanding by the people who own it has been dumbfounding. And ultimately, the arguments for it all become arguments against it when pushed enough. It has been laughably rejected as a store of value. So now it is either a Ponzi, a greater fool theory, or a speculative hope. And hope is not a strategy.

How bad is it in commercial real estate?

“Can you elaborate on your statement from the last Dividend Cafe that hand-wringing over commercial real estate is overdone? Why do you believe defaults will be less than expected and that recoveries will be higher than expected?”

There are two principles driving my view here: (1) Whenever everyone is talking about something, it never ends up being the drama (up or down) people anticipate. Something can’t be a big shock to the system when everyone thinks something is about to be a big shock to the system; (2) The post-2008 lesson in commercial real estate sticks out. Residential real estate fell apart in 2007 and 2008 and, of course, credit markets really fell apart. There were plenty of defaults in commercial real estate loans, particularly in assets bought in 2004-2006 (overpriced vintages). However, the chorus in 2009 and 2010 was almost consensus – “the carnage has not gotten bad enough in commercial; after residential finally washes out, wait until the shoe drops in commercial real estate; another bloodbath coming …” What played out was, well, not a bloodbath. Defaults happened, new owners traded hands in some cases, many opportunistic buyers made a bloody fortune buying distress, and actually, many asset classes in commercial real estate proved to be wonderful buying opportunities. But systemic failures that would halt economic activity? Nope, not even close.

I believe it is quite clear that most macro commentators do not know what they are talking about when they paint with a broad brush about some asset class called “commercial real estate.” The idea that multi-family housing or data storage is the same asset class as industrial warehousing or healthcare facilities is absurd. The idea that development deals levered to up 80% or 90% loan-to-value is the same thing as a stabilized property with 50%+ equity is absurd. The idea that San Francisco is the same thing as New York City or that either is the same thing as Nashville, Tennessee, is absurd.

Banks work with borrowers when distress events happen unless they perceive it to be in their best interests not to. There was far more equity in commercial projects coming into this period than there was in 2007/2008. The high dispersion of circumstances in America’s commercial real estate category leads me to the conclusion that the fate of some bad strip mall in a depressing town with no sponsor backing cannot be perceived as the same as a well-run hotel asset with stabilized cash flows and high protective equity.

Too many banks

“Given regulatory constraints are practically guaranteed to increase in the U.S. after SVB, Signature and First Republic, do you expect bank M&A to increase in the U.S.? I don’t see why the U.S. needs literally thousands of banks versus, say, Canada where there are six main banks that are practically government-sponsored enterprises.”

Well, there are a few points of view here. On one hand, I do believe there are more small, community, and mid-sized banks than the marketplace needs, and therefore believe there will be a long period of M&A in banking ahead – of strategic and sensible consolidations. I suspect our own Treasury Department and FDIC want to see such a thing. On the other hand, the notion of quasi-GSE banks – latent nationalism – is a putrid idea for a market economy. Competition for advising on capital, stewarding capital, trading capital, and all of the other components that financial institutions provide is a very good thing for the same reason that competition is good in any sector – it creates incentives for better services, quality, pricing, and so forth. Why banking and financial services would be immune to this law of economics is beyond me.

Banking has the ability to be a growth engine where adequately capitalized firms bring ideation and innovation and human capital to the table. Generic retail banking – taking deposits and lending money out at a spread – lacks a lot of opportunity for productive innovation. But, it creates opportunity for local and regional relationship lending that is a huge positive to their customer base.

Making the DMV become the national bank will lead to less investment, less savings, less lending, less capital markets, less innovation, and ultimately, more pursuit of foreign financial partners up to the task of 21st-century banking.

Alternative to what?

“Do alternative investments help to provide better returns with lower risk? If so, why don’t we put more money into them? If not, why do people invest at all?”

Many people seem to base their advocacy or implementation of Alternative Investments on a false premise – that “you can have market returns with lower risk, like magic.” Our philosophy regarding alternatives is not the pursuit of “equal or better returns with less risk” – but, rather, “a different return driven by a different source of risk.” Not better or worse or higher or lower – different. The pursuit of some diminishment of portfolio beta – the risk that is broadly market risk and not able to be diversified away – does not mean “diminishment of all risk.” It means replacing the risk known as “market risk” with more idiosyncratic risks. That is vastly different.

Do unto others as they do unto you

“Both Britain and the U.S. have significant budget and current account deficits. Debt to GDP in both countries is at or close to 100% of GDP. Britain has raised its rate in the last month aggressively, and the Bank of Canada recently did as well. Is any of this predictive of what is coming to the U.S.?”

No, each country has a wide array of circumstances that make its situation different from one another. The major issue the questions misses is currency ramifications, where one country being more dovish than another could weaken their currency too much, and one country being more hawkish than another could cause their own currency to strengthen to a point of non-competitiveness with others (in trade). The United States is hardly playing catch-up with other central banks in this tightening cycle. One can agree or disagree with what the Fed or any other central bank does, but I would be very cautious about trying to predict which central bank is leading the pack.

Funny you should ask

“What books would you recommend on a) qualitative stock analysis and b) portfolio management for the dividend growth investor?”

Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor is a value-investing work of art.

My own The Case for Dividend Growth is meant to be my holistic treatise on the subject of dividend growth investing. Lowell Miller’s book on the same is also quite spectacular (The Single Best Investment).

I believe of the tens of thousands of pages of investment (security) analysis I have read over the last 25 years, far more were in journals, symposiums, and white papers than were in books. That is probably less true for macroeconomic analysis, which is completely distinct from bottom-up fundamental analysis. In both disciplines, the book/non-book intellectual resources are a split.

FedNow or FedLater

“If my memory serves me right (and it doesn’t always), you have said the Fed doesn’t have the know-how and capability to create a central bank digital currency (CBDC). Is the new FedNow service not a CBDC or is it just a wannabe that will not succeed?”

It is essentially a payments service. Banks have used SWIFT and federal funds wires and ACH and all sorts of money movement infrastructures for many years (all under the purview of the federal government). FedNow is intended to be a real-time payments service, and we’ll see how banks like using it. But no, it is not a CBDC – as a currency is a liability of the issuer; there is no currency being issued with FedNow. It is merely a transfer of payments service. I am skeptical of our central bank’s ability to penetrate into either domain very successfully.

Stock returns and the future

“My question today is regarding stock returns. Since World War II stocks have averaged 12% per year. You regularly warn us that growth moving forward is unlikely to be anywhere near that which would result in returns like that. If you had to hazard a guess, what would you say stocks will average the next 20 or 30 years?”

You will probably insist you have no idea and you are too humble to make such a prediction, but you must have some idea of a ballpark figure. Are you expecting meager returns of only 5% due to the ravages of Japanification, or something more in the ballpark of 7% or 9%? The expectation of returns half that of what we have enjoyed in modern times would be nothing short of monumental in terms of the difference it would make in planning for retirement!”

Stocks have returned 11.1% since World War II. And you are correct – for anyone to even make a guess, let alone the pretense of an educated guess about the asset class return for the next thirty years, would be utterly irresponsible.

And since it is totally immaterial to the way we manage money, and in fact purposely immunized by the way we manage money, it really is not something I find important.

I do believe Japanification will disrupt the retirement plans of a lot of index investors or closet index investors. But what 30-year equity returns will be contains so many variables, influences, and unknowns, it is silly to venture a guess. Dividend growth immunizes me from this concern.

Free Trade, Fair Trade, and Funny Trade

“Isn’t it unethical/wrong to produce a good somewhere else just because the workers there make less money? Wouldn’t it be a precondition to free trade to somehow level the playing field?”

I think I will answer your question with a series of questions:

- What is the criteria for a “level playing field” and is such a thing (totally level) remotely possible in the real world?

- Who ought to determine what is a level playing field – the buyers and sellers in a transaction or the governments of the country where the buyers and sellers live?

- Does one import goods from “countries” or from “companies that are in other countries”? Is that distinction relevant? (hint: yes)

- If it is unethical to produce a good somewhere just because it is cheaper to make it there (due to less health benefits paid to workers, for example), wouldn’t it also be unethical to consume such a good (perhaps more so)? When we consume goods, do we know all needed information about the economics for workers relative to other potential manufacturers? If the answer is that we don’t, and ethics are on the line, do we have an obligation to find that out before we buy something? And why would that burden stop at the border? Should I find out wages and benefits information of a place selling me a burger for $8 relative to a place selling me one for $6?

I do believe the answers I would offer here can be deduced, but I actually think honestly working through them as questions may be more fruitful. I hope it is a constructive reply, as I did intend it to be.

All locked up

“How do companies pull profits out of China with the Chinese government’s tight control of capital markets?”

Various non-Chinese companies have various agreements with China about capital controls and movement. Most Chinese companies do not move profits made in China out of China. Hence the competitive advantage companies with a free flow of capital have over countries that do not …

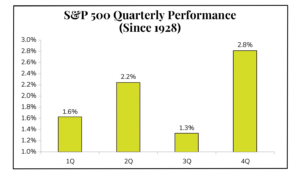

Chart of the Week

Calendar occurrences over 95 years contain lots of variance above and below the mean. That is a fancy way of saying that this is an irrelevant and non-actionable chart. But it sure is interesting!

*Strategas Research, Quarterly Review in Charts, July 5, 2023, p. 3

Quote of the Week

“The very existence of libraries affords the best evidence that we may yet have hope for the future of man.”

~ T.S. Eliot

* * *

Of course, we are happy to take on any other questions you may have. No subject is off limits. I do hope what we covered this week scratched some itches, and I hope you are as excited for earnings season as I am. That will launch near the end of next week and ought to provide a lot of information about the state of corporate America and guidance into the near-term future.

In the meantime, steer clear of the noise and root for what is best for you long-term. To those ends, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet