The following is a compilation of a Special Series on the Ten-Year Anniversary of the Financial Crisis of 2008 highlighted in the Market Epicurean on the exact dates of some of the most historically significant financial happenings of our time. We have also added short videos for each of the Ten Parts, a Podcast of the recap, and a link to download a printable version of everything you see here.

PART ONE – Getting Your Fannie Whipped

View Or Download Entire Series As A PDF Booklet

As we launch a multi-part series to cover the ten-year anniversary of the financial crisis, let us not forget the most important thing people need to understand about the crisis itself: September 2008 is not really the month “it all began.” We are choosing to follow this calendar guide because virtually everyone will remember, for good reason, the events of September 2008 as the milestone moments they permanently associate with the financial crisis. indeed, the entire month ran for me as a really bad mini-series, with each episode actually more traumatic than the one prior. September 2008 was the most significant month of my career, and perhaps the most important month in capital markets since October of 1929 – but it was neither the beginning nor the end, of the financial crisis (the “Great Recession”). Rather, it was the manifestation of so much of the financial crisis – a crisis that had been building for many, many years.

I wrote a year ago that August 2007 was probably the more accurate month to call the “crisis launch” – for it was August 2007 when credit markets really broke. The subprime market went bust, and financial traders began realizing losses en masse around derivative positions that were completely and totally unknown in size to the rest of the world (as we now know, basically to the heads of the firms themselves). Fall 2007 created a dislocation in swaps, in CLO’s, in subprime synthetics, and began a spiral of big-firm write-downs. A couple of mortgage hedge funds at Bear Stearns went bust. It was brutal. But no one will ever associate it with “the financial crisis,” because the dam didn’t burst. Equities didn’t peak until late October. The run on Bear Stearns didn’t climax until March of 2008. At this point, the world was still turning with mostly functioning capital markets. It was September 2008 when everything came together – and that is why it will represent the focal point of this series.

I do intend to try and captivate you with a play-by-play of my own reminiscing through that month’s events. Certain days and milestone events stick out more than others, and I have chosen those truly vivid memories and iconic occurrences to focus on in this series. I recognize my own recollections and biographical context may not be captivating at all to many of you, but it is the optimal way for me to explore such a profoundly significant month in American economic history. I really hope you will find the series of short articles beneficial, if not captivating.

Too many people talk as if the domino of financial catastrophes started in September with the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, for certain, that was (and always will be) the marker by which we look at the permanent changing of Wall Street. But we should never forget the event that actually preceded Lehman’s fall by eight days – one with even greater significance to taxpayers to this day – and that was the government’s seizing of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac on Saturday, September 6.

Part One Video

The history is actually really easy: Fannie and Freddie were created by acts of Congress as “government-sponsored enterprises” – a term so nebulous and non-specific, you can be forgiven for assuming it meant they were official government agencies. They were not. They were publicly traded corporations where shareholders kept profits – not government bureaus. However, this public-private milieu meant that they functioned with a sort of implicit backstop from the government, giving them the ability to issue far more debt than anyone could imagine, at far lower cost than any other private actor. We now know, of course, that the real stirring of a brutal mortgage and housing bubble were well under-way before the spring of 2008, yet in the spring Fannie and Freddie continued to add to their pool of leveraged subprime securities. By July of 2008, Treasury Secretary, Hank Paulson, sought and received permission from the Congress to guarantee $25 billion of Fannie and Freddie bonds (a laughable number relative to the $5 trillion of mortgages Fannie and Freddie had guaranteed). The same bill sought to give the Treasury Department other means and tools should they be necessary for the future. (To this day, I believe the Secretary that in July, when he sought this “bazooka,” as he famously called it, he did not know or believe that he would end up having to use it).

By September 6, things had completely and totally unraveled. Demand for Fannie and Freddie bonds dried up as domestic and foreign investors sought the security of Treasuries and some greater assurance that the Federal government would backstop this exposure. Mortgages rates flew higher (a 30-year fixed mortgage at 6.52% – imagine that!) – and Fannie and Freddie were in a death spiral. Like a Ponzi scheme, they required continued funding from capital markets to sustain their highly leveraged balance sheet, and as that crisis of confidence blew up new funding, the death spiral had arrived.

The government put Fannie and Freddie into “conservatorship,” which essentially wiped out their stockholders completely. The equity was worthless anyway, but global markets needed to know there was a backstop to the mortgage obligations that had an “implicit guarantee” from a “government-sponsored enterprise.” Everything transcended “implicit” and “sponsored” after September 6.

My wife and I were driving for home from a weekend anniversary trip when the news broke. My immediate response was one of anger – I had been an outspoken critic of the whole concept of Fannie and Freddie for years. I am sad to say, my immediate response was not to understand what systemic damage this would mean for the whole system. For indeed, while Fannie’s common stock was dead (for good reason), and their bonds were now backed by the government, they had $36 billion of “preferred stock” outstanding, capital the holders of which were sorely counting on! Ultimately, the realization that these capital instruments were not safe meant that a whole lot of capital instruments were not safe – and that chain reaction did not move slowly.

By market open on Monday, the 8th, commercial paper was called into question, along with Lehman’s ownership of Fannie preferred stock, along with, well, almost everything else. The week that followed would serve as the final calm before the week that forever changed Wall Street.

***

PART TWO – Ground Zero: The Fall of the House of Lehman

On Sunday afternoon, September 14, 2008, I had spent some time playing in our backyard swimming pool with my kids, when my blackberry began blowing up. Throughout the morning notices and alerts had been coming about a possible deal between Lehman Brothers and mega-UK bank, Barclays. Now, my kid time was being interrupted by the rumor that deals were falling apart, and only Secretary Paulson could save Lehman Brothers. In other words, a government bailout was coming, or Lehman was going to declare bankruptcy. I broke away to my home office with the door shut, CNBC on, and computers and mobile devices running, for the remainder of the evening.

To properly contextualize what all came next, and what it meant, some background information is desperately needed. Lehman will remain the “name at the center of the financial crisis” for the rest of time, but in reality, they were, but one of the over-leveraged Wall Street firms brought to their knees by the housing and credit bubble. The difference between Lehman and some of their key competitors was that Lehman had been unwilling or unable (or in actuality, both) to raise capital as the shoe began falling earlier in 2008. The capital buffers firms like Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch raised with China, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and more would all prove inadequate (as we will soon see in this series), but the market still trusted them to some degree, they had greater access to the repo market (overnight funding which was the primary source of liquidity for many Wall Street firms), and they had raised some equity capital (albeit expensive capital with a highly preferred coupon). Lehman was a different story.

Bear Stearns failed under the weight of their own debt spiral and a liquidity trap in March of 2008. It was widely understood that Lehman was second in line as far as financial behemoths tied to mortgage-related assets and excessive leverage on the balance sheet. Treasury Secretary, Hank Paulson, spent months pleading with Lehman CEO, Dick Fuld, to raise more equity capital. Time and time again, Fuld came up empty, claiming would be investors were “low-balling” Lehman in what they would pay for a piece of equity in the firm. That decision would prove to be the undoing of this once great legendary firm.

Lehman’s toxic assets stemmed from an unprecedented buying spree in the mortgage space throughout the 2000’s (well into the later innings of the housing bubble), acquiring multiple subprime mortgage lenders and becoming a massive securitizer themselves of mortgage assets. Comments have been made that Lehman became a sort of real estate hedge fund, and not an actual investment bank. In 2007, as their own subprime lenders were closing their doors and the market was falling into an abyss, Lehman pressed down, underwriting more mortgages than any other firm on the street, and pushing their mortgage assets to over four times their actual equity. No attempt was made throughout 2007 or early 2008 to divest any portion of the toxic mortgage balance sheet they had accumulated.

Part Two Video

Coming into 2008 over 31x levered (let’s define what that means – they had assets equal to over 31x their real shareholder equity), the vulnerability to any disruption in the market was severe. When Bear went down, attempts to raise liquidity from preferred stock or dumping commercial mortgage pools at fire sales prices, were wholly inadequate. What the firm needed was real life capital, and it had no ability to raise it without recognizing severe impairment to its equity value. Of course, a bankrupt, $0 equity would end up being the real impairment, a far worse outcome than what they were trying to avoid.

I wrote last week of the collapse of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac that took place on September 6. The week after Fannie’s demise, Lehman stock continued to plunge, and I took solace every day that I didn’t own any of their stock (or Fannie’s or Freddie’s for that matter). I also believed that I was potentially really missing the boat, as surely CEO Fuld would pull off a deal, and surely the stock had oversold relative to its real value. Alas, I couldn’t muster up the courage to place a bet that Lehman would find a savior. The rumors of a big deal with the Korea Development Bank fell apart (just days before the bankruptcy, Fuld still felt they were “under-valuing his company”). The stock dropped another 45% in price, but more telling; the credit default swaps spiked over 70% (the cost of insurance on their debt). I was, for the first time in my career, more focused on the cost of the debt insurance than I was the stock itself.

I left the office Friday afternoon convinced they would secure a deal over the weekend, with the worst case being a government bailout that wiped out the equity but staved off contagion, and the best case being some savior that restored equity value in the company. I was half-sick at the idea that I missed a chance to benefit from the panic on Lehman opportunistically.

Meanwhile, Ben Bernanke, Hank Paulson, and the CEO’s of the leading banks on Wall Street spent their weekends holed up in Manhattan trying to find a solution to save Lehman Brothers. Bank of America looked at the books and walked away (tomorrow’s piece will focus on what they did end up spending their time on). Barclays got the closest, but couldn’t get the permission from their regulators to close in time (a decision that should have resulted in Barclays sending flowers and gifts to their regulators every day for the rest of time). By Sunday night, as I sat glued to CNBC in my home office, desperately calculating what collateral damage my clients may face from the Lehman fall, it was clear that Lehman was a goner.

Much controversy has swirled around the government’s decision not to bail Lehman Brothers out. Fed Chair Bernanke and Secretary Paulson and then-NY Fed head (and future Obama Treasury Secretary, Tim Geithner) have all insisted they lacked the legal basis for doing so. They are certainly correct that they lacked the legal basis to do so, but I suppose that is different than saying they could not have done so without some creative will to make it happen. However, my own estimation is that they knew it was too late. The exposure in financial markets to toxic assets and debt in excess of the value of assets was past the point of a bailout – Lehman’s balance sheet had infinite vulnerabilities, and the complete and almost dramatic lack of appetite for partnership with them in the private sector gave no motivation to the government to put its hat in the right. The public policy decision was, “if someone is going down, we’d rather it be the 5th largest investment bank than the 1st, 2nd, or 3rd.” My opinion ten years later is not that the government was right or wrong to allow Lehman to go into bankruptcy – it is that they did not have a choice. The painful process of debt liquidation was, at this time, inevitable, and no real path existed to will it away.

I did not sleep that Sunday night, and obviously, the many fine folks at Lehman Brothers did not either. $600 billion of assets existed on the balance sheet of Lehman, and this bankruptcy had no chance of ending well. The inter-connectedness in the financial markets was so opaque and substantial that clarity of exposure and damage was not going to come easy. The market dropped the next day at the same level it did after 9/11. Money market funds with exposure to Lehman commercial paper were “breaking the buck” (dropping below the $1 per share par value depositors relied on). We will discuss the remaining contagion effects that hit the market the 15th, 16th, and 17th of September in the days ahead.

But what happened on Sunday night, September 14, launched the most infamous week in Wall Street history, and one of the most unforgettable weeks of my career. Counter-parties no one was thinking about faced the threat of extinction. Credit markets were not merely tight; they were utterly frozen. No one with a remaining brain cell trusted anything from anybody. A spiraling effect had taken down Lehman Brothers, and now was looking for its next victim. It wouldn’t have to look far.

***

PART THREE – Mother Merrill Gets Adopted

In the aftermath of the Lehman bankruptcy announcement, the market closed down over 500 points (-4.4% ) on Monday, September 15, 2008. The fact of the matter is – had it not been for the second biggest announcement markets were absorbing, that point drop could well have been double what it was.

For in the commotion of the Lehman failure, specifically, the inability of Lehman to get a deal with Bank of America or Barclays, a second shock & awe event to Wall Street took place, and that was the acquisition (rescue) of Merrill Lynch by one highly generous Bank of America. And as history would go on to prove, Bank of America’s passing over Lehman to buy Merrill Lynch proved to be a case of refusing to open up dynamite so you could instead drink poison.

I will get back to why this announcement actually soothed markets a bit in a moment. First, some history. Merrill Lynch was Wall Street. No firm better defined the ethos and image of Wall Street than Merrill Lynch. They were an impeccable brand, with an extraordinary legacy, and their financial advisors were 15,000 of the proudest and well-branded on the street. “Mother Merrill” as they were known, was the standard for the rest of the street. They were the innovators of so much of what existed out of Wall Street brokerage firms. President Reagan’s Treasury Secretary, Don Regan, had been CEO of Merrill decades earlier. Their use of the “bull” image was legendary in American folklore of financial markets. They made famous the line, “bullish on America.”

But by September of 2008, America was not bullish on Merrill Lynch.

Merrill Lynch’s president, Greg Fleming, approached their Goldman alum CEO, John Thain, as the weekend of Lehman’s demise was unfolding. Bank of America had passed on a deal with Lehman Brothers. That meant that the street would then wonder who was next – meaning, who would face the liquidity spiral that would escalate into a solvency crisis next. Greg was convinced it would be Merrill Lynch. They had become a leader on the street in the production of CDO’s (collateralized debt obligations, and were flying high in 2005 and 2006 around these silly mortgage instruments. Merrill often transferred some of their risk for these CDO’s by entering into credit default swap transactions with famed insurer AIG (the story of tomorrow’s piece), but when even AIG said they would not ensure this exposure anymore in late 2005, Merrill kept on generating CDO product (often holding it on their own books), unhedged and deeply levered. By 2007, it was not a laughing matter. By 2008, their CDO mortgage exposure brought the company to its knees. The $26 billion of write-downs in their CDO assets (that they kept on their books) was still less than half of the $71 billion of mortgage toxicity dragging Merrill’s balance sheet down. Like Lehman, they faced a collapse under their own leverage once the street refused to transact with them, or counterparties demanded more collateral. Fleming convinced Thain they needed an equity partner to take them on.

Part Three Video

And that is where Bank of America would do a world of good for Merrill Lynch, while nearly collapsing their own company. Had markets re-opened Monday absorbing the death of Lehman Brothers, while also believing Merrill Lynch faced a demise of confidence, the counter-party systemic risk would have been monumental. Instead, the markets absorbed a pure investment bank with no real capital backstop being absorbed by a commercial bank with a couple trillion dollars of deposits in its funding base. And not only would Merrill Lynch now have a backstop for their seemingly infinite mortgage liabilities, but Bank of America was also offering them $29 per share (essentially, over $40 billion of value). It was surreal (and even today, remains absolutely baffling). This was 70% higher than its price before the weekend started, and I ask you – would the value have been higher, or lower, after that weekend of utter destruction? The offer was double Merrill’s own stated book value, a book value that everyone on the street knew was going to face more write-downs.

So on Monday, September 15, as the markets went into absolute pandemonium, Merrill Lynch actually rose 1% in value, while Bank of America declined over 21%. By February of 2009, Merrill’s stock would be gone (having been absorbed into Bank of America), and Bank of America would trade as low as $3 per share, reflecting the combined value of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch. The reality is that along the way, Bank of America would desperately try to get out of the deal, but to no avail.

Wall Street and Main Street saw a vaulted brand, rich in history and achievement, absorbed by a Charlotte-based commercial retail banking chain. Merrill shareholders may not have felt like anyone was doing them a favor (there had still been extraordinary value deterioration throughout the crisis, and Merrill’s valuation was pegged to a ratio with Bank of America, so the economics of the deal would only functionally get worse). But the overpayment for the Merrill asset will remain one of the great stories of the 2008 crisis, perhaps as much for what it kept us from ever finding out versus what it did reveal. Could the U.S. economy have actually absorbed the death of Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch in the same season? The Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve certainly didn’t feel so, as we would later find out. Their aggressive efforts to prod that deal along towards closing would become the subject of intense scrutiny and litigation in the months that followed.

The week that forever changed capital markets in the United States is only through Monday, September 15, and two of its most heralded brand names are now gone – Lehman Brothers to bankruptcy, and Merrill Lynch into the arms of Bank of America. And we’re just getting warmed up.

***

PART FOUR – Bailout Bombs Begin

So, we now get to September 16, 2008, the economy in total free fall, the feeling of global credit market collapse in the air, and thus far, the government has not actually become the central player they would eventually become.

But that would not be true by the end of September 16.

Like Merrill Lynch, AIG had been founded in the early part of the 20th century, rich in history, heritage, and brand. A leading life insurance and annuity company, AIG was a respected financial products innovator, known for respectable cost management practices, and a true U.S. success story. When regular folks on Main Street thought about Wall Street, the stock market, securities trading, corporate finance, and the mortgage market, none would have affiliated such terms with AIG. A host of other Wall Street brand names from Merrill Lynch to Bear Stearns would have come to mind, but not old line insurance company, AIG. For most people, AIG just wasn’t at the heart of Wall Street, let alone the U.S. mortgage market.

That disconnect apparently had existed at the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department as well.

I took my son, Mitchell, then three years old, to Disneyland, the afternoon of the 16th. I had promised him and his mother all Summer long I would take an afternoon off to do so, and I had been working 20-hour days for a week straight as this crisis was fomenting. Leaving the office near the end of the market day this Tuesday was not easy. The Dow had actually gained back 1.3% (from its 4.4% loss the day before) as naïve traders began to wonder in the aftermath of the Lehman deal if things weren’t getting a little cheap. But nothing felt stable and the unknowns were overwhelming. I kept my word and went to Disneyland with my wife and son, with a work-issued Blackberry in one pocket and a personal iPhone in the other (the 1.0).

Space Mountain was not as wild as the afternoon of emails, texts, alerts, and news cycle drama would prove to be.

The Federal Reserve waited until the market closed to announce that they were injecting $85 billion into AIG, firing management, and effectively taking over the company. AIG had been asking for a “government loan” of $40 billion on Sunday night, and the government had told them to pound sand. Less than 48 hours later, the government was singing a different tune.

Part Four Video

At the heart of this decision was the reason AIG needed the assistance, to begin with – they were the guarantor of risk for financial institutions all over the globe via the credit default swap market. Effectively, AIG had been the counter-party in an insurance contract on so many of these mortgage instruments that various financial firms had been writing. For an insurance premium, AIG became an insurer of the securities. These premiums were unfathomably profitable for AIG during the boom years, as defaults on these instruments were 0%, payouts were 0%, and the expression “there is no free money” appeared to be laughably untrue. But now with the mortgage market in pandemonium, AIG’s liabilities on the other side of these trades were far, far in excess of their total capital. Their own solvency was not only blown away but the fact that counter-parties all over Wall Street (and across the pond) assumed they had “hedged” certain positions meant everyone else’s solvency was called into question.

To make it as simple as possible, financial firms like Goldman Sachs may have had a $1 billion exposure on a Certain Mortgage Derivative or CDO, but if they sold credit default swaps with AIG on that, they may have figured they had a net exposure of, let’s say, $250 million. But if AIG could not pay, not only was AIG out all of their capital, but Goldman was out the $250 million they thought they had at risk, and the $750 million they thought they had insured. The collateral damage (no pun intended) to each other company around AIG’s insolvency was staggering. If Goldman’s marks on their books were impaired, that meant everyone else’s was, and everyone else traded with each other, too, all based on certain presumptions of financial wherewithal. The domino effect was incomprehensible, not merely because it was hard to measure, but because what could be measured was stupefying.

So just like that, the Republican Bush administration and the Federal Reserve were throwing in the towel on the idea of a financial contraction that would not involve the heavy hand of government. The Fed injected $85 billion (to start), at a very high coupon of 8%, and took warrants for 80% of the equity of the company. In most countries, we call this nationalization. It was not a bailout of AIG, other than in the literal sense that it obviously was, but rather a bailout of the counter-parties of AIG. This was never adequately explained to the American people, in my opinion. All focus had now charged to limiting contagion risk.

And as we will see in the days ahead, this contagion was no longer hypothetical. All hell was breaking loose. Money markets were falling. Commercial credit was non-existent. AAA-rated companies were having a hard time rolling over the debt. And trust in the financial system was at the lowest it had been since the Great Depression.

“Your first bailout will never be your last.”

Disneyland may have been the happiest place on earth that day. They didn’t have any credit default swaps.

***

PART FIVE – Is Wall Street Dead? The Day Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs Looked into the Abyss

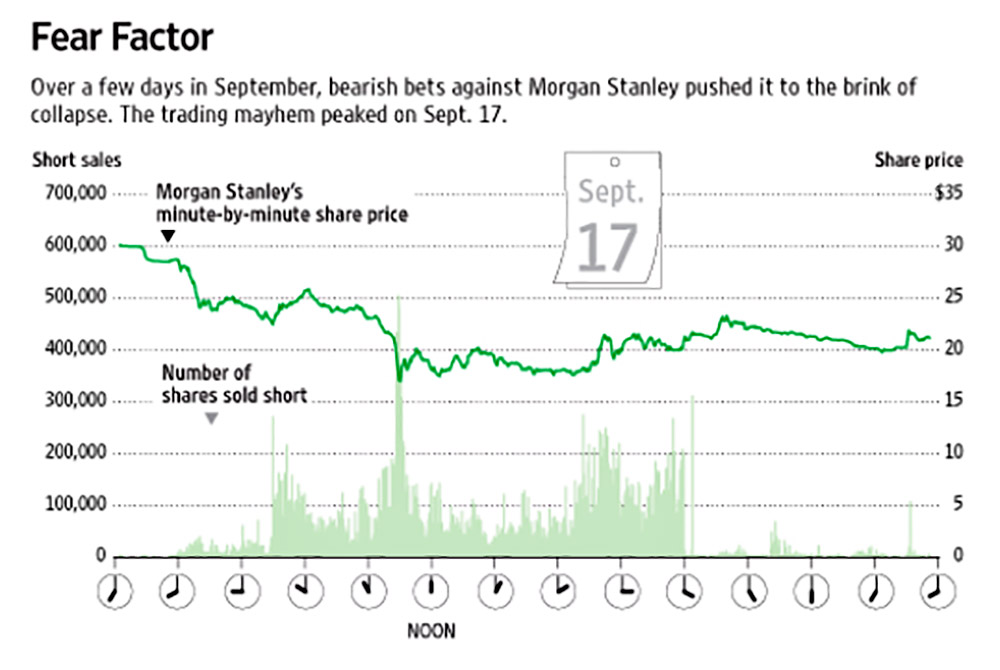

If reading our series so far has given you the impression that September 14 (Lehman’s bankruptcy), September 15 (Merrill swallowed up, market down 500 points), or September 16 (AIG bailout, money markets collapsing) were stressful days, then I am not sure what the appropriate adjective would be to describe September 17, 2008.

My late father, who passed away in 1995 at the age of 47, would have been 60 years old on Sept. 17, 2008. That day always involves a certain degree of emotion. This week and season were obviously producing entirely enhanced levels of emotion and anxiety. And on this particular day, a few things were particularly noteworthy. The stock market dropped 450 points, the second worst day of the year (the Monday, two days earlier, had been worse). This represented the market hitting a 3-year low.

But in addition to living through the onset of this recession (which was growing worse by the day), the macro issues in the U.S. stock market, the clear stress, and uncertainty in all aspects of the financial sector, and the pain and fear clients and investors were dealing with, I was, at the time, a Managing Director at Morgan Stanley, one of the leading investment banks on Wall Street. Until a few months earlier, Morgan Stanley had felt reasonably good about how it had held up throughout the crisis. Its stock had declined throughout 2008, as all stocks had, but compared to Bear Stearns and Lehman even before their combustion and even compared to Merrill Lynch and Citibank, it felt relatively better about its positioning versus competitors (it had large mortgage write-downs, but not at the same level that some other firms had). On September 17, the fears moved from the broad boulevard of “Wall Street” to the actual address of “Morgan Stanley.”

In the middle of the day, the stock dropped fully 24% from its opening level, as rumors persisted that Morgan’s demise was next. Goldman Sachs also saw its stock drop over 15%, both around concerns for the firm’s ability to sustain adequate liquidity. The costs of the credit default swaps for Morgan Stanley’s debt had skyrocketed (meaning, the cost to insure the debt was way up, indicating a heightened fear of a big problem). One rumor circulating was that Deutsche Bank had taken away a $25 billion credit line (this ended up being untrue). Short sales skyrocketed (mostly hedge funds betting against the stock price).

A controversy persists to this day – are the shorts betting on an outcome, or creating an outcome? (the accurate answer is neither – they are “betting” on an outcome they genuinely believe is coming, while also potentially facilitating that outcome if the entity is over-leveraged). We received a company-wide email mid-morning that the firm was a victim of vicious and opportunistic attacks by short sellers. We had a conference call later that morning where that same message was reinforced. Clients were panicked about the safekeeping of their own money. And it wasn’t even 10:00 am yet.

Part Five Video

We now know that many hedge funds were bidding up the cost of the credit default swaps (signaling distress in the credit quality) while simultaneously shorting the stock (creating a self-fulfilling prophecy). John Mack, the CEO of Morgan Stanley, launched a very public effort to ban short-selling, an effort that would succeed, unfortunately for Morgan Stanley (what I mean is that a few days later when the SEC announced a ban on short sales of certain financial stocks, legitimate financial actors who lacked an ability to hedge risk and exposure they had turned to the bond and CDS market to find their protection, creating a negative feedback loop for Morgan Stanley; it also so angered certain high-profile hedge funds that they pulled money from Morgan’s prime brokerage business, adding to market signals and anxiety).

The level of hysteria and panic and volatility and insanity in the market can best be demonstrated by this: One of the large rumors circulating that day was that Wachovia was looking to buy Morgan Stanley. Within days, Wachovia themselves were on the brink of death (a future issue in the series coming) and would themselves be bailed out. The hunter and hunted were trading each other’s hats every day.

By the end of the week, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs announced that they were becoming “bank holding companies.” Their formal structure as an independent investment bank was over. Like Citigroup, JP Morgan, and Bank of America, this means that Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs could now benefit from the capital cushion and funding mechanism of a client deposit base. This move would intensify regulation on the respective firms dramatically and would reduce their leverage levels by over 60% (imagine that!).

The regulatory framework, financial metrics, and culture of the firms would not be the only thing that changed this fateful week. The Wall Street model would be forever altered. The capital structures of the firms, reliance on the repo market for funding, and inter-connectedness to each other for debt funding would all be revealed as a source of monumental systemic risk. Market solutions would not be easy to find due to the lack of understanding surrounding these complex behemoth institutions. A new relationship between government and Wall Street was coming, as was a new relationship between Wall Street and her customers. And her advisors.

Morgan Stanley did end up surviving the financial crisis, and a few months later, were themselves switching hats from hunted to hunter. The days of being “swallowed up” by JP Morgan or Wachovia were gone, and instead, Morgan Stanley was buying Smith Barney from Citi for a tiny fraction of the prestigious wealth management firm’s former value. This would take place in January 2009. Oh, what a difference just a few days makes, eh?

But back to September 17, 2008, months before Morgan was buying other companies on the cheap, they were themselves on the brink of extinction. Reports that the Federal Reserve released years later would reveal that they had borrowed emergency sums of money from the Fed discount window to keep the lights on during this time. They did keep the lights on, and John Mack negotiated a deal to sell 20% of the firm to Mitsubishi, providing $9 billion of desperately needed capital. That phone call from Mitsubishi, coming on CFO Kelleher’s cell phone on a Sunday night at San Pietro restaurant at 54th and Madison in midtown Manhattan, saved the firm.

I will never forget the October Mitsubishi deal that saved Morgan Stanley, but I will really never forget September 17, 2008.

Oh yeah, happy birthday, dad. I assure you, I thought about him a lot that day.

***

PART SIX – By Any Means Necessary: The Fed’s Alphabet Soup is Born

We last left off in this little “mini-series” on September 17, which in 2008 fell on a Wednesday. The four successive days of September 14-17 saw the fall of Lehman Brothers, then Merrill Lynch, then AIG, and on Wednesday, the 17th, the near-death experience of Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. The couple of days off since are not due to a calm, serene couple days back in the corresponding days of 2008. In fact, in the 72 hours after the initial batch of catastrophes, a slew of events took place, each one individually perhaps forgettable, but the composite milieu of which represented a stunning paradigm shift in national policy.

And we must reiterate, these were catastrophes that were caused by the financial crisis, not the cause of the financial crisis, and yet they served as perfect fodder for a negative feedback loop.

On September 18, 2008 (a Thursday that was following three brutal days), the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 410 points (+3.9%) – making back much of the downturn of the day prior (but nowhere near the downturn of the whole week). The market had been flat throughout the day, up one minute, down the next, but trying to figure out its next move after a nearly thousand point drop the first three days of the week. I was glued to my computer screen, resisting all temptation to start heavily buying the market, believing [rightly] that things were just too unstable and uncertain to know exactly what to do just yet. I can’t even recall how many clients I spoke to on the phone that day, and I began sending email updates (bulk delivery) to as many clients as I could, as frequently as I could. I had sent the first of such electronic communiques the day prior as some clients were understandably petrified about what they were seeing on the news regarding Morgan Stanley (where their own funds were being held).

This practice of frequent “email updates” (largely to give more current updates to a greater number of people with greater efficiency) was absolutely born in this very week of the financial crisis, but it simply never stopped. Today, it is called Dividend Café, is a macro commentary covering all aspects of investing, and has over 4,000 subscribers worldwide. 🙂

With less than an hour left in trading on the 18th, markets unable to yet launch a comeback rally in the aftermath of recent bloodshed, Charlie Gasparino, famed markets journalist then in the employ of CNBC, jumped on air to say that he “was hearing reliable rumors of a massive, system-wide bailout being planned by Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson.” By the end of trading, we knew that President Bush had been visited by Fed Chair Ben Bernanke, Hank Paulson, and SEC chair Christopher Cox. The rough idea being floated was some mechanism by which the government could take some bad debt off the bank’s balance sheets. The market rallied violently, despite having no specificity of details, or certainty of passage. That lack of certainty around passage would come back to bite all parties in a couple weeks, and the lack of specificity of details would really become relevant. But for that hour, and into that market close, with credit markets still deeply clogged, and systemic uncertainty around the fate of Wall Street, investors bid up the market 4% out of the hope that Uncle Sam was coming to the rescue. By the week of October 6, the idea of nationalization potentially taking place would no longer seem so rosy – and would actually create one of the worst market weeks in America history. But for now, some signs of life were being perceived.

Part Six Video

On Friday, September 19, markets started to get more clarity on what direction Ben Bernanke was willing to go in his leadership at the Fed. The Fed actually opened a guaranteed liquidity facility for banks and businesses that needed capital but had their “cash” in money market accounts that were temporarily broken. Never lacking for a clever name, the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) was born (it rolls off the tongue). The idea that the banker of last resort, responsible for a stable monetary policy so as to stimulate full employment but stave off inflation, was now providing unlimited capital to businesses having trouble with their money market funds was stunning. It also may have saved the financial markets.

Of course, what the central bank was doing was working to inject liquidity, and the markets needed it, desperately. But what they could not do is inject solvency. At this point, the root of the crisis was the solvency of global financial powerhouses over-levered to an unfathomable degree. Backstopping money markets were not going to work.

From the days that followed, and in continued evolution in the time that passed, the Fed ended up launching a Term Auction Facility (TAF), a Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), and a Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF). They also launched currency swap agreements with several foreign central banks outside the United States. By the end of the crisis, they had also launched a Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF), and the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF). Alphabet soup was alive and well. All of these policy tools were essentially versions of injecting liquidity to banks and financial institutions (legal under the Fed charter if there was adequate collateral) or injecting liquidity directly to borrowers and investors (unheard of).

It is my opinion that in the days that followed Lehman’s bankruptcy, Ben Bernanke and Tim Geithner had an epiphany. Gone was the idea that this was a bad moment, but one that would pass after the market absorbed the loss of a couple of big companies. In was the idea that these were unprecedented times, and would call for unprecedented action. Ultimately, the seriousness of Ben Bernanke’s resolve to place desperation over ideology would be demonstrated time and time again in the months and even years that followed, with “rules-based” central banking tossed aside, and a bazooka-like approach implemented. Good intentions in a time of pandemonium did likely give birth to some unpleasant monetary developments as well (QE3, Operation Twist, etc.).

But for now, in the third week of September 2008, something was happening minute by minute live on my TV, computer screen, blackberry, etc. The leading central banker in the world had gone from vehemently opposing Fed support to Lehman Brothers, to lending AIG $85 billion and taking over their company, to creating an alphabet soup of “facilities” by which questionable assets could get Fed support to keep the lights on. Hank Paulson and Ben Bernanke would begin begging Congress for additional support and powers. The Fed was moving into its own aforementioned liquidity powers. And Bernanke himself was admitting it was a “finger-in-the-dike” strategy.

I am not totally sure that Chairman Bernanke had much of a choice but to just go from one leak to the next by the time this fateful week arrived. Ultimately, the financial crisis was about to go down two different tracks – the fiscal side involving Congress and the taxpayers, and the monetary side involving Federal Reserve policy.

As Washington Mutual and Wachovia will tell us next, we were living in unprecedented times. And Ben Bernanke was now up to speed.

***

PART SEVEN – WaMu, FDIC, and other Four-Letter Words

When Bear Stearns went down in March of 2008, 100% of Wall Street was familiar with the venerable financial giant, but I suspect a very small percentage of Main Street was. And in September of 2008, again, 100% of Wall Street knew Lehman Brothers, but I doubt a large percentage of regular folks did. Both Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers were top 5 investment banks (the others being Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch), pillars of finance, institutional trading, asset management, prime brokerage, and so much more. But they were not commercial banks – branded on Main Street – brick and mortar type shops which people routinely visited or interacted with.

Throughout late 2007 and into 2008, the financial crisis was underway, meaning, the most preposterous of bubbles that our national housing market had become was well in the midst of a violent burst. Housing prices had cratered, real estate and construction-related jobs were disappearing, and the consumer spending boom of 2003-2006 that had been made possible by home equity extraction was collapsing. And yet, the corporate failures of September 2008 were, so far, mostly on the “Wall Street” side of the fence. Lehman, Bear, even Merrill, and Goldman were elite white-shoe firms, and while things like money market failures and TED spread widenings had profound impacts on Main Street, the headline connectivity was not yet there.

Now, before I make the point I am about to make, you will recall that in January of 2008, Countrywide Financial, a significant retail brand name in the mortgage space, had fallen into the loving arms of Bank of America (an acquisition that should go down in history as one of the most cursed, value-destructive deals ever known to mankind). Bank of America would pay $4 billion for the firm which at that time had essentially a negative $45 billion value (based on settlements and fines that would end up being paid). Countrywide was certainly a household name, but their failure was not doing damage to Americans as much as Americans inability to service their mortgages had done damage to Countrywide. Systemically, Countrywide being swallowed up by Bank of America had no impact on the lives of Americans.

Washington Mutual was a different story. This behemoth household bank, heirs of the old Home Savings & Loan brand, particularly known up and down the western United States, was a respected banking franchise, well-branded, and formerly associated with smart underwriting and disciplined banking practices. By September 25, it would be the largest banking failure in American history.

Washington Mutual (WaMu as it was commonly known) had 20% of its loan book in loans with 0-10% down payments. That may seem like a conservative figure, but when multiplied by its volume and the inevitable default rates in this low-quality segment of the mortgage market, it became devastating. The bank earned profits of $3.6 billion in 2006 but took losses of $6.7 billion in 2007. The secondary market for mortgage-backed securities was dead, and WaMu was holding toxic assets on its balance sheet, and in a desperate liquidity pinch. What was keeping it alive was customer deposits.

Part Seven Video

>That all changed after the Lehman bankruptcy. $16.7 billion was withdrawn in the next nine days, a classic “run on the bank” if there ever was one. The FDIC was monitoring the situation, still reeling from the July bankruptcy of IndyMac. On Thursday the 25th, they announced that WaMu did not have sufficient funds to function. The FDIC has a rather tight and defined process for “winding a bank down,” handling the insurance of depositor funds, and implementing a transition. But their experience was not in taking over failed behemoth banks, just small ones. Like everyone else, the FDIC turned to the Fed in this tumultuous time, and the Fed (and Treasury) reinforced that there would be no federal government bailout outside of FDIC protocol. However, they turned the matter over to JP Morgan, and JP Morgan was all too happy to jump in.

I remember seeing the headline come across my screen that the FDIC was seizing Washington Mutual (it was Thursday the 25th and I had arrived in New York City for what would be an unforgettable week in our nation’s financial capital). I can’t recall how much time went by between the first headline of the FDIC’s seizure, and the second headline that they were selling the bank to JP Morgan for $1.9 billion, but it was less time than it took me to unpack my suitcase in midtown Manhattan. The fact of the matter is that JP Morgan between its Bear Stearns acquisition and the WaMu deal did receive some very quality assets, at very low prices, that would represent long-term value for the shareholders of JP Morgan. But at the time, WaMu didn’t even have another bidder (a reflection of the impairment across all bank balance sheets), and JP Morgan (under their famous “Chase” banking moniker) would end up writing down $31 billion of bad debt. They added $300 billion of deposit base but had to inject $8 billion of capital to keep the lights on.

The WaMu failure represented two profound moments in the crisis: (1) It was a retail Main Street name that reinforced how broad the carnage was in this crisis, even well outside of Wall Street; and (2) The bondholders were wiped out. As we will see in the months ahead, besides the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, there was no carnage that was allowed to happen to the bondholders of these firms. From the Fed/JPM bailout of Bear Stearns back in March to the countless deals impacting Fannie, Freddie, and TARP-firms, bondholders got made whole. But not at Washington Mutual. The policymakers obsession with protecting bondholders did not apply to WaMu – a historically significant fact.

The crisis would reel in a couple more banking giants in the days ahead (see tomorrow’s issue), but only WaMu would end up in the pile of massive banking names brought down by reckless lending practices and a run on the bank that no banks in a fractional reserve system could ever survive. JP Morgan’s purchase of Washington Mutual averted the disaster that faced depositors and allowed the Fed and Treasury to re-focus on their next priority: Wachovia. It also allowed the FDIC to stay liquid and solvent, as there would be plenty of smaller bank failures which would have a healthy need for the FDIC’s resources.

Wall Street and Main Street were now inexorably linked.

***

PART EIGHT – What a 20-Block Walk Can Mean to the Fate of a Gigantic Bank

I arrived in New York City on the evening of Thursday, September 25, 2008, in time to take in the failure of banking giant, Washington Mutual. I also arrived without luggage (the one time in over 250 trips to New York City in twenty years that luggage was lost). If lost luggage, a week representing the collapse of capital markets, and the failure of one of the largest banks on the west coast were all not enough, USC also lost to Oregon State late that night in on an ESPN Thursday Night Football game that would end up being our only loss of the season. Yes, things were really bad.

Friday, September 26 was another substantial day in the financial crisis. Senator John McCain announced he was “suspending his campaign” to focus on the financial crisis, a political stunt that won over absolutely no one. I spent the day in various meetings and found myself leaving a meeting at 36th Street and Madison Avenue at approximately 2:00 pm. My blackberry went off as I walked into a little restaurant to grab a late lunch. “Citigroup closer to acquiring Wachovia” was the headline at that time. A beverage and meal later, I began a walk down Madison Avenue where I was meeting people at 54thStreet. By the time that walk was done, I had received three more alerts on the blackberry – one suggesting that a large bank in Spain was looking at Wachovia, and one suggesting that Wells Fargo may jump in the fray. If you will recall, just a week earlier, rumors were flying that Wachovia may buy Morgan Stanley. I actually have this literal progression sorted out in vivid memory:

9/17 – Wachovia to buy Morgan Stanley

9/19 – Goldman Sachs to buy Wachovia

9/24 – Wachovia passing on buying Morgan Stanley and passing on selling to Goldman Sachs

9/26 – 2pm – Citi making offer to buy Wachovia

9/26 – 3pm – Banco Santander considering a bid for Wachovia

9/26 – 4pm – Wells Fargo making offer to buy Wachovia

It was an exciting week in Charlotte, NC! (Home of Wachovia Bank, then the 4th largest bank holding company in the U.S.)

Part Eight Video

As it would play out, Citi formerly offered to buy Wachovia for basically $1 per share, but with the FDIC absorbing any losses in a $312 billion mortgage pool Wachovia owned after $42 billion of losses. The FDIC and Fed announced that this deal was entering the final stages. The deal was not going to include the Wachovia brokerage business (itself a conglomerate of Prudential, First Union, Everyn, and AG Edwards). The Wells Fargo offer came during a period Wachovia and Citi were exclusively negotiating and involved no government backstop at all. The deal was essentially for $7 a share.

(Remember that when I say “basically $1 per share” and “essentially $7 a share,” it is because these types of deals are actually done at an “equivalent” ratio in stock of the acquiring company. So one can compute what the economic value to the seller was at the point of the offer, but the ending economic value fluctuates as the stock value of the buyer fluctuates; the ratio stays the same, but the numbers are not so black and white).

James Gorman, CEO of Morgan Stanley (still today) told us at a closed-door meeting in 2009 that the capital hole in Wachovia’s balance sheet was $25 billion. Well, the cost of their purchase of Golden West Financial in 2006 was, you guessed it, $25 billion. Golden West was a famed subprime mortgage provider known for their use of negative amortization loans. Wachovia Bank had $671 billion of deposits, but the capital hole in their balance sheet from somewhat inexplicable mortgage acquisitions, combined with a run on their bank the day after WaMu went down, had left Wachovia beaten and left for dead. Wells Fargo had the balance sheet to make the purchase without government support, and Wachovia’s board jumped on the deal.

That final weekend of September would encompass some real drama for millions of Americans. Across midtown Manhattan, there was a palpable sense of dread, fear, and uncertainty. The world was now two weeks past the death of Lehman Brothers, and Congress was to vote on Monday on the idea of a “TARP” relief package to re-instill confidence in America’s financial system. If fatigue was setting in on what had become of American capital markets and her premier financial institutions, the weekend would prove to be little aid in addressing such fatigue.

Wachovia became the latest institutional casualty in this financial crisis, and I banked another memory – of a 20-block walk so eventful, I hardly remember the meetings before and after it.

***

PART NINE – This 777 Was A Crash, Not a Landing

I woke up in New York City Monday morning, Sept. 29, dreading what was to come. By now it had been two calendar weeks since Lehman Brothers had declared bankruptcy, yet those two weeks felt like two calendar years – not just for the markets and news calendars, but for me personally. Because my own firm at the time, Morgan Stanley, had apparently calmed their own waters by selling a large portion of themselves to Japanese bank, Mitsubishi, and re-organizing as a bank holding company, the anxiety around my own firm’s viability had subsided (though it would be violently re-provoked the first weekend of October, when that Mitsubishi deal was allegedly falling apart; by Monday morning the deal closed and deep breaths were taken).

But on this Monday morning, September 29, I knew several things: I was meeting with some very nervous and scared clients that day, the House of Representatives was voting on the TARP bill that day – the resolution the Fed and Treasury Department had put before Congress to attempt to stabilize markets – and that dominoes had not stopped falling yet. As part 7 and 8 of this series highlighted, we were still absorbing Washington Mutual and then Wachovia just days before, and I was not getting used to a daily wake-up thought of, “which gigantic U.S. financial institution is going to go out of business today?”

It was a high anxiety period, to say the least, but at the same time, it was my job. I was glued to my various electronic devices because I was determined to communicate with clients early and often as their anxieties warranted. I met with a Manhattan client of mine at 8:00 am for breakfast this somber Monday morning at the power breakfast Loews Regency venue at Park Avenue and 61st Street. I do not recall what my client ordered, but I do recall what I ordered – scrambled eggs, bacon, and a side of fruit. I recall that, because when the server came to clear our dishes, my plate was still completely full – with scrambled eggs, bacon, and a side of fruit. Not a bite of breakfast was eaten (by either of us). The emotional wear and tear were becoming a factor physically.

It is important to contextualize something for you in the midst of this series which has obviously been focused on the headline drama of financial firm failures and large M&A transactions. While markets were dealing with major events like the Lehman bankruptcy and the AIG bailout and the corporate rescues of troubled firms like Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, and Wachovia, it isn’t like the rest of the world had shut down. Other market-relevant news was still coming – news of the “normal variety” – and it, too, was atrociously bad news at each and every step. News of Washington Mutual being shut down by the FDIC was not exactly interrupted with a report of industrial production growth or decent jobs data. The market was absorbing all sorts of extraordinarily bad news, intermittently announced between all sorts of regular bad news. Commodity prices – tanking. Manufacturing – collapsing. Jobs data – no one could predict high enough losses. Auto sales – worse than expected. Consumer confidence – please. You get the idea. The bad news was broken up with other categories of bad news.

I believe it was noon that day that I met with another client for lunch at a patio outside of 30 Rock that we had met at several times over the years (Morrell’s Wine Bar & Café). We had some specific matters to discuss relevant to this client’s situation, but of course, the conversation was overwhelmed by the state of markets and state of affairs. At 1:00 or so when we ordered our lunch we both looked at our blackberries to see the market down 400 points. I put mine down and looked at my other phone: CNBC alert after CNBC alert that the House may not have the votes to pass the TARP bill. I made a couple calls and nibbled on a few pieces of cheese we had ordered on the cheese platter (which would become the entire sum of my food consumption for the day).

“Do you need to go trade this drop?” he asked me.

“Anyone stepping in today to buy or sell is going to get their faces ripped off,” I replied.

In the middle of a market panic, selling exacerbates the problem and indicates a foolish understanding of market mechanics. But panic-buying can be equally reckless. A sober and judicious time to re-evaluate asset allocations would come (for me it would come Wednesday, October 1 in the Admirals Club at LaGuardia Airport wherein four hours I re-allocated one hundred client accounts myself – this was before I had two full-time traders working for me!).

At 2:30 pm the market was down over 500 points. At 3:00 the market was down over 600 points. At 3:30 pm the market was down over 700 points. And by the 4:00 pm-close, the market would be down 777 points, the all-time record drop on a points basis for the DJIA (obviously the percentage drop was worse on Black Monday in 1987). But this percentage drop was not laughing matter either – down 7% on the day, and within a month that had already had plenty of 3, 4, and 5% drops. The VIX (fear index) spiked up 33% – to an all-time high of 46.72 (for context, it sits around 11 or 12 most of the time today). And how did “international diversification” help equity investors? The UK market was down 15%, and Brazil was down 10%. (“Correlations go to 1.0 when you need diversification most”)

Part Nine Video

The market would rally back on Tuesday when the Senate passed TARP and it became clear that the House would be re-voting. But let me make something very clear for everyone: For all the good and bad that can be said about TARP, the idea that it ever calmed stock markets is insane. The TARP bill failed on September 29, and the market tanked 777 points. True enough. But on October 3, the House re-voted and passed the bill (there is nothing like an 800-point drop in the Dow to scare the blank out of elected officials). The market opened on October 3 at 10,483. It went as high as 10,800 that day around hopes for TARP passage. Well, TARP passed, and the market closed that day at … 10,325 – almost 500 points off its intra-day high. We would open Monday, October 6, with TARP now the law of the land and $700 billion to be injected into the country’s financial system, at 10,300. A week later we were at 8,500 on the Dow. History does not seem to recall that the market dropped almost 2,000 points – a stunning 20% more – after TARP passed.

The reasons are actually not that complicated. TARP had been presented as a mechanism to “buy toxic assets off of the balance sheets of our financial institutions.” Within days of its passage, it became obvious that they had a change of heart – they were going to directly inject equity into these companies and take a stake in them – a sort of quasi-nationalization that pummeled their stock prices further. At this point, markets had absolutely no confidence about anything, and presumptions for worst-case scenarios were prudent and commonplace. Fears were rising that even the TARP bill itself had under-estimated the financial hole embedded in banking balance sheets. Some of these fears actually did come to fruition – even after the TARP intervention, Citi would end up needing over $200 billion of additional “government backstop” in November. Bank of America would aggressively look to abandon their disastrous acquisition of Merrill Lynch, only to be told it was in the “national interest” for them to complete it. There were zigs and zags throughout the fall, but no level of market normalcy was achieved in October of 2008 – just continued declines.

Our concluding contribution to this series will highlight when and why the markets did finally begin their stabilization and restoration.

On this September 29, 2008, Monday afternoon, things soon turned into early evening. A city with 4 million people working in it each and every day felt like an absolute ghost town. My night time meeting canceled on me (a money manager who would soon lose his job). I walked up and down the streets of midtown, just listening to the sounds of uncertainty that one could feel in the air. I sat down at the bar at Ben Benson’s steakhouse at 52nd Street between 6th and 7th Avenues. I hadn’t eaten any real food all day, and I had a few hundred emails to respond to and clear out. I nibbled at my steak a bit (even in the midst of global market panics, a medium-rare ribeye is hard to turn down). The mood in this bustling, landmark steakhouse was catatonic. I literally sat there wondering if Lehman’s bankruptcy had hurt their business (the 745 Seventh Avenue headquarters of Lehman were just around the corner).

Ben Benson’s would close their doors a year later. There was no TARP package for midtown steakhouses.

***

PART TEN – Tying It All Together: What The Financial Crisis Meant and Means to YOU.

It would be impossible to do justice to the financial crisis of 2008 in just ten parts, let alone a tenth part that ends on October 2. As a couple previous issues referenced, by October 2 the House had not even passed TARP yet (that was the 3rd). The week of October 6 became one of the worst weeks in market history as a 10,300 open on the Dow that week resulted in an 8,450 close. The stock market drop was becoming unthinkable, and we were now four weeks past the demise of Lehman Brothers!

I have written in each of the last nine articles of vivid memories related to specific instances and milestones in the crisis. The truth is that by mid-October, much of the crisis became a daily routine. The high drama of a new bank or iconic firm failing had subsided, and instead, we were just stuck in, well, a crisis. Markets teetered at 8,500 from all of mid-October to mid-November, going to 8,000, and then above 9,000, but unable to really figure out where a bottom could make sense. One famous Tuesday (the 28th) saw the market rally almost 1,000 points from open to close in one day. No matter how bad things were then, and they were bad, a 1,000 point rally day understandably reinforced the futility of trying to trade around the horror of the market. Those with equity exposure at that time were already in the drama – to try and exit after this multi-thousand point drop seemed silly. Yet that did not mean the markets were done going down. It just meant no one knew. I didn’t know. And no one else did either.

I remember the Friday afternoon that President-elect Obama announced Tim Geithner to be his Treasury Secretary. The markets went up 500 points. Instead of wallowing in the 7,000’s we would spend the remaining months in 2008 (November and December) wallowing in the 8,000’s. November also saw another bout of what I called “before Asia opens” – the Sunday night drama where the financial media is forced to break into special coverage – and some urgent drama is covered as needing reconciliation before markets in Asia opened (i.e. their Monday morning). We had plenty of such moments in the peak portions of the crisis, and then we got a resurgence in November when all of a sudden Citi was on the brink, after receiving $25 billion of TARP money. Only when the U.S. government promised to backstop an unfathomable $306 billion of risky assets in late November did their bonds come back from the dead. Stability was still a ways away.

The first quarter of 2009 may have been more gut-wrenching than the fourth quarter of 2008. Fatigue is a huge factor in a bear market. The shock and awe of quick and violent drops in the market can be brutal for investors, but when it continues with [what feels at the time] like no end in sight, it is mentally and emotionally exhausting. The problem in January and February was that markets still were not clear what the Obama administration planned to do around the financial crisis itself (resolution of the banking industry at large), and full-blown nationalization was not off the table enough to satisfy investors. There were days that President Obama would go on TV, and the market would drop 300 points. Then Secretary Geithner, would go on TV and it would drop 300 points. I recall one client asking me “if they go on TV together (split screen?), does that mean we will drop 600 points?”

Of course, the “real world” ramifications of the recession were dominating the tape (collapse of corporate earnings, massive unemployment, total cessation of productive economic activity). It would have been impossible for circumstances to be much worse. And yet, stock prices in late February (the low 7,000’s) were no longer pricing in a recession, or even a horrid recession – they were pricing in the failure of the American economy. That has never been a very good thing to bet on.

Part Ten Video

Part Ten Podcast

On Friday, March 6, 2009, I sat in an economics conference at The Breakers Hotel in Palm, Beach, FL, trying to listen to the speakers (which included a plethora of elected officials, Federal Reserve governors, Treasury Department personnel, and various economists), but simultaneously working on my laptop. I served as the trader at that time, in addition to being the portfolio manager, and as markets hit what would become a generational bottom (666 on the S&P 500 and 6,469 on the Dow), I just sat there buying – wherever I had available cash to do so. The time had come. I had no idea that was the bottom – none. But I wrote to clients then, “we do not need to know that this is the bottom; we only need to know that we are surely far closer to a bottom than the top; that the risk-reward trade-off has moved in our favor; that our financial goals are better served at this point by buying than selling.”

I was back in my CA office on Monday, March 9, and within days I would never see a 6 in front of the Dow Jones Industrial Average again. And by the end of April, it would never see a 7 in front again. The stock market would end 2009 up 25% in the S&P 500, and up well over 60% from its intra-year bottom in March 2009.

The market had opened 2008 at 13,338. It’s opening day price on January 2, 2008, would be its high for the year.

In 2017, the opening day price would be the low for the year. What a difference a decade makes.

But let’s talk about the decade that was between 2008 and now. Has this been a bull market for the ages? Sure, in the sense that the market has a technically positive return nine years in a row (it appears the tenth year is on track), and that the % return in the market is over 300%. But has it been a straight line higher? Of course not. We had a thousand point drop in a day in the so-called “flash crash” of May 2010. We dropped 20% in the S&P 500 in the summer of 2011 as Europe appeared to be on the brink. The market went two years without advancing at all (in terms of start to finish) from mid-2014 to early 2016. The market dropped violently in August 2015 and January 2016 around China fears. It dropped another 1,000 points around Brexit in mid-2016. It has confounded critics, devastated bears, shocked bulls, and done so with little regard for anything other than the machinations of markets themselves.

Markets are measurements of sentiment in the short term. And they are measurements of value in the long term. Same as it ever was.

The lesson of 2008 in terms of an investor’s life is not how to time the exit from markets or time the re-entry – for no one can do that. It is not how to place huge “big shorts” on bubbles – though books and movies on those who did so are admittedly fascinating. One hedge funder who made about $8 billion shorting subprime mortgages has since lost over half of that – first on gold, then on an over-levered pharmaceutical company. A few billion here and there and soon you’re talking about real money. Easy come, easy go. And never confuse luck for talent.

Look, the financial crisis was the most brutal economic period of American history outside of the Great Depression, and certainly the most challenging period of my career. But the financial crisis was only fatal for one type of investor – the person who capitulated to the fear.

This is not to insult the person who capitulated (though it may be to insult their financial advisor). Human emotion, nature, and psychology were not calling for “measured maintenance of a disciplined asset allocation” when new companies were failing every Sunday night. Markets dropping 20% can hit us, but 50%? And just a few years after the tech crash? With tens of millions of boomers ready to retire? Hell hath no fury like two bear markets in one decade …

But the fact of the matter is that 2008 should be the greatest lesson we will ever get in the downside volatility capacity of risk assets. “Why don’t I have the exact same return of equity markets?” is a question only those who can say, “I am willing to take the exact same downside volatility capacity of risk assets” should ever utter. Asset allocation is a tool to blend the risk and reward potential of various asset classes into a coherent portfolio targeting a desired return, within an acceptable level of risk. It is not perfect. But it sure beats the arrogance that 2008 punched in the mouth – the arrogance of, “I know when the market will be up, and when it will be down, and when it will be back.” No, you don’t. No, I don’t. No, that person doesn’t either.

Those who mocked the possibility of a housing bubble were humbled in 2008. Those perma-bear newsletter writers who mocked the idea of a market recovery were humbled ever since. Humility is the way of a mature portfolio manager. And truthfulness better be – or you won’t be in business for long.

The truth is that I do not know when the next recession will come, but I do know one will come. I do not know what will cause it, but I do know what will solve it. And it is out of that latter statement that we should draw this to an end.

The purpose of risk asset investing is to generate a return that will enable you to meet your financial objectives through time. Because of inflation and time-realities, that generally cannot be done without a risk premium – a return above the “safe rate” of treasury bills (which you will note went to 0% during the years after the financial crisis) – or a denominator of money so high that the investor is willing to just spend down their own capital. The accumulation of capital requires a premium return to beat inflation, taxes, and time – and in the great companies of the country and often the world one can find a growth of earnings and dividends that can play a vital role in one’s achievement of return premium, and through such, the achievement of their financial goals. But that requires human behavior (and more often than that, non-behavior) that can withstand macro events like war, natural disaster, and economic crises. It is a trade-off – we pursue a better return to meet our goals, and invite occasional migraines along the way.

The 2008 financial crisis was not a mere migraine. But it was a reminder about all the other infirmities that markets will give us in our investing lives. We cannot predict the future. Yet we must behave with discipline and faith. Trusting in capital markets to resume their pursuit of efficient, rational use is hard to do when it feels like there is an economic tornado coming. But trusting in your own ability to time your way in and out is an exponentially riskier endeavor.

I hope to never go through an event like the credit crisis of 2008 again, yet I know we will go through bad times again. I am significantly more confident, read, researched, and competent than I was ten years ago, and yet I also am significantly more humble. I can read 10,000 more pages of investment research, but when the madness of crowds kicks in, I will be unable to “think” my way out of it on behalf of our clients. What I can do, and will do, is call on every lesson of 2008, every lesson before that, and every lesson that ever will be …

And they all come down to this:

Free markets work. The profit motive works. Optimism is the only realism. The world doesn’t end. Even bad crises end. The arc of history is on the side of the disciplined investor.

And family, friends, and faith, trump all. Even 2008.