Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I suppose I ended up deciding on the obvious topic for this week’s Dividend Cafe, but as of Wednesday afternoon, I was still undecided as to the direction. The universally pre-known outcome of the FOMC meeting was not especially noteworthy, but then the post-meeting commentary began, and I began to break out in hives at the absurdities being uttered. There is a lot going on right now that intersects with Fed decisions and Fed expectations, so today’s Dividend Cafe will look at all of it – the housing market, the state of inflation, the tariff impact, and some underlying politics in all of it.

We’ve heard it said that the Federal Reserve’s job is to take away the punch bowl when the party is getting to be too fun. Well, my job is often to not touch the punch bowl (and I don’t). Having fun is not our aim in the Dividend Cafe – but it can be a lot of fun. It’s just going to be the sober kind of fun.

And today that means a sober view of what the Fed is doing and why, and what I believe it means for investors in this somewhat murky time. If you want to skip the reading and get straight to the bottom line (or to the punch bowl), I believe investors would be wise to hold on to a properly constructed portfolio now, tomorrow, and for years to come thereafter – and to do so without speculation of what the Fed will do or not do. Fed governors come and go, and Fed governors make mistakes. Our job is not to join them in making such mistakes. And so to that end, we work – delivering our view of what the Fed is doing and why, as well as the far more important takeaway of what investors should be doing and why. If I do my job right, you will see that the latter is not really that connected to the former!

Let’s jump into a very special FED issue of the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

What They Did

Simple enough: The Fed cut rates a quarter point (as expected), bringing the Fed funds rate to a target range of 4% to 4.25%.

He also informed us that the Fed is “rolling off” a whopping $5 billion/month from their balance sheet at present (all Treasuries). So, you can say “quantitative tightening” is still ongoing, but it has slowed to a crawl, and I can’t totally understand why they would be doing any at that level, other than to say they are doing it.

There is $35 billion/month of mortgage-backed securities that are maturing and being “swapped” into Treasuries, but this has a net-zero impact on the size of the Fed balance sheet (easing vs. tightening) and only deals with the composition of the balance sheet.

Bottom line: the first rate cut in nine months, and a snail’s pace (a slow, decrepit snail that makes the other snails look fast) of quantitative tightening. After this cut, policy remains restrictive – not accommodative – and not even “neutral” (yet). The question that I seek to answer below is whether or not the Fed is headed to a neutral or excessively accommodative place.

What They Said

The written announcement only softly addressed weaker jobs data:

“Job gains have slowed, and the unemployment rate has edged up but remains low. Inflation has moved up and remains somewhat elevated.”

But they took away the July verbiage that “labor conditions remain solid.” They also said that “downside risks to employment have risen.” The press conference added more color as Chairman Powell referred to the cut as a “risk management cut.” He was abundantly clear in addressing the risk in the dual mandate and the concerns around price stability (inflation) vs. full employment (economic growth) that “there are no risk-free paths now.” He stated that the Fed is in a “challenging situation.”

About That Balance of Risks?

The jobs data has been the subject of recent Dividend Cafe commentary and a great deal of media commentary, and for good reason. There is legitimate concern in the vast BLS revisions, the major slowdown in ADP payrolls growth, and even some questions about the initial weekly claims data.

Now, the 264,000 weekly jobless claims from last week were followed by a 231,000 number this week, once again seemingly reassuring markets that the bottom was not falling out in at least that data set. I can’t reiterate enough – a general average in initial weekly claims of around 225k per week has been more or less maintained for well over three years now. Bond yields moved higher right after the report came out—a sort of relief move relative to the concern that jobs data was cracking sooner than later.

But does this mean all is well in jobs land? It most certainly does not. To be clear, the four-week average in initial claims has gone up to 240,000 (in the range of the last 3.5 years, but at the high end of it). The aforementioned weaknesses in BLS data, ADP data, and QCEW revisions are impossible to ignore. I would suggest that initial claims “hanging in there” indicates a lack of firing, where a big pick-up in weekly claims would clearly mean that a “hiring freeze” has transitioned to a “firing acceleration.” The latter does not appear to have happened (yet?). But the issue the Fed is talking about, and certainly the one I believe we ought to be talking about, is the hiring freeze. A healthy jobs environment is not merely the absence of mass terminations, but also one in which robust new hirings take place. And that is not the environment in which we find ourselves, hence the “balance of risks.”

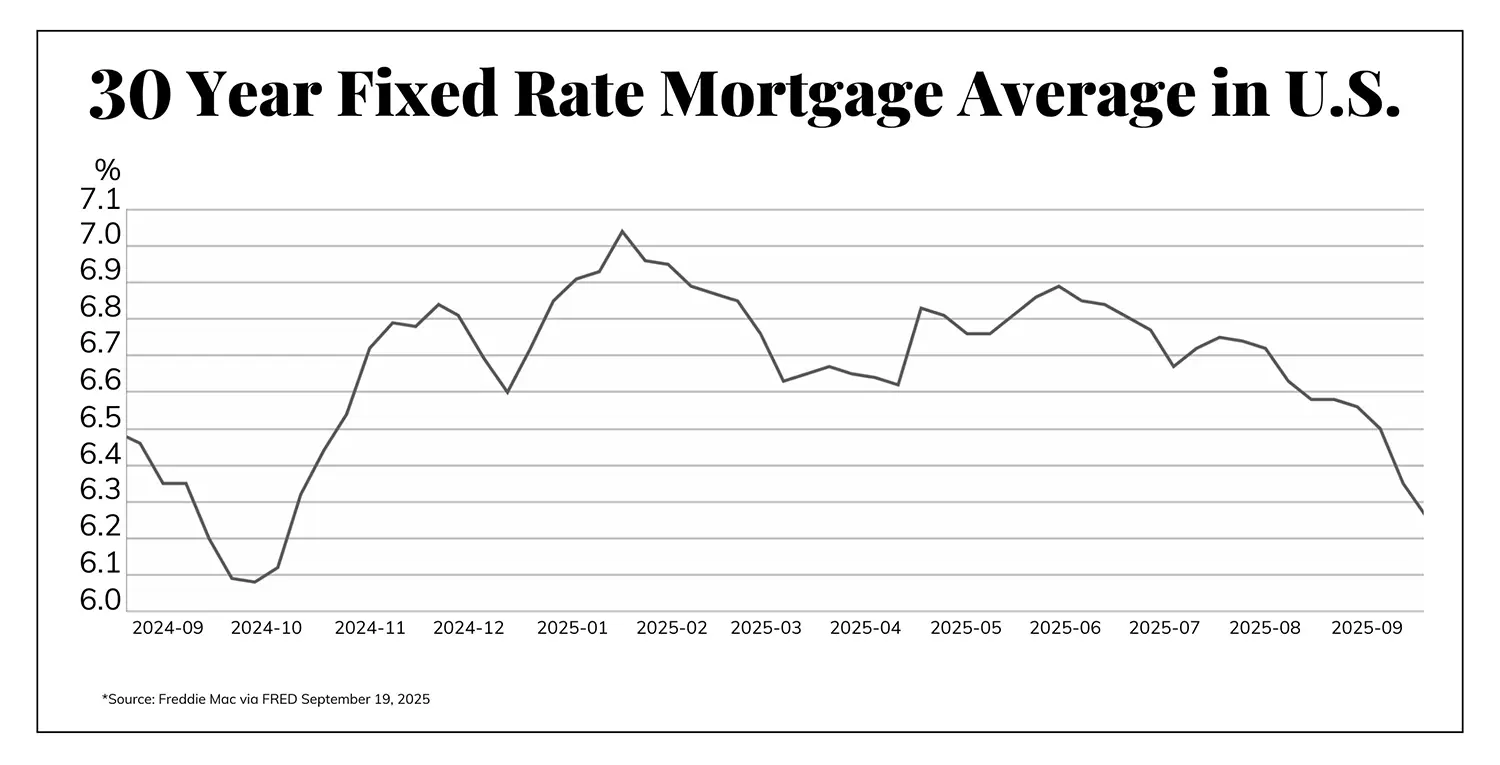

What was not so much said out loud, though intimated on occasion, is the Fed’s concern about the housing market in their rate calculus. You see here where mortgage rates were a year ago before the Fed first cut, how mortgage rates quickly dropped but then quickly went right back up, and yet how over the last couple of months mortgage rates have dropped (from 7% to 6.26%) in advance of the Fed’s cutting (and in line with the drop in the 10-year bond yield).

Market Response

Stock markets were quite mixed, with the Dow up after the Fed announcement, but both the Nasdaq and S&P were down. All three indices were up on Thursday. More notably, bond yields spiked lower for a minute and then moved higher. As of press time, the 10-year is sitting at 4.10%, having hit 4.0% on Wednesday. The better-than-feared initial jobless claims number on Thursday is part of that.

But the major thing to remember here is that, well, there wasn’t one single person on planet earth who didn’t know going into Wednesday’s meeting that they were cutting a quarter-point. Why the immediate market volatility after the announcement, then, and more of such as the Powell presser played out?

Because this. Always. Happens. Always. Say it again, please – always. There are a few factors at play, but none of them are relevant to TBG and our clients. There are hedges on that have to get taken off. There are hedges off that have to be put on. There is a high frequency response to what Powell may say or not say. And there are some of the dumbest gamblers God ever let walk through the door, placing big bets on some six sigma event. Normalized trading takes a minute in the aftermath of both a Fed announcement and a Fed chair press conference, and I do not say that as a testimony to the natural intellect of all mankind. But it is true.

Now, would markets have gone down if the announcement had been, “We are not cutting rates and not going to any time soon?” Yes, they would have. But that was never going to happen. And if it did, I have a sneaking suspicion the Trump administration would suddenly find a problem in one of Jerome Powell’s T&E submissions (if you know, you know).

Why Did They? Why Should They?

The Fed cut rates yesterday because they are unnecessarily restrictive in a time when the economy is vulnerable, when the jobs data is concerning, and when the high cost of capital is burdening certain sectors of the economy needing a looser grip (commercial real estate, housing, small business borrowers, those competing against tariff pressure, those needing to embark upon capital-intensive projects, etc.). The Fed is not wrong that the balance of risks has moved from price stability issues to economic strength (what they have labeled in their mandate as “full employment.”)

Why should they have cut rates? For all the reasons they did. I would summarize my view with these four basic statements:

- The Fed has a restrictive approach right now when it ought to have a neutral one.

- There is a massive amount of commercial real estate debt and smaller business loans that face rate resets in the next year, which the Fed is well aware of, and if resetting at present rates and rate spreads, would be highly restrictive for the economy. This is a huge catalyst for Fed easing.

- The housing market is frozen as would-be sellers are on strike due to the low rates they enjoy on their existing mortgages. The “unfreezing” of the housing market to bring supply and demand into equilibrium and avoid adjacent economic hits from this ongoing housing freeze requires lower rates, and while the Fed Funds rate cannot make the long-end of the yield curve come down, it is supposed to directionally help if the curve does not widen.

- The Fed is right about a “balance of risks,” and those wondering about the strength of the labor market are right. Going from restrictive to neutral is appropriate in the present circumstances.

- That all said, going from restrictive to neutral to excessively accommodative is my concern, and also what history has said central banks tend to do.

Real Housewives of the Federal Reserve

There is a lot of drama happening inside the Fed right now, and the political environment is intensifying the drama, to say the least. We already know that President Trump wants Jerome Powell out (not new news), and we know that he has accepted that illegally firing him would do more harm than good. We also know it is reasonably moot in terms of real-life monetary policy since the chairman’s term ends in May anyway, and the court battle that would take place if the President did fire him would likely last that long.

Please note, when I say it would be illegal for the President to fire the Fed chair, I am merely repeating the same conclusions that the White House has come to. I am aware some people believe the President should be allowed to fire the Fed chair without cause, and there are Constitutional questions in that subject that are perfectly legitimate for reasoned debate. But for my purposes here, I am merely pointing out that as the law is set now, Powell cannot be fired, and all indications are that he will not be. I also believe it is pretty irrelevant for markets … He is going to be replaced by the President in about eight months, and markets know it.

But the more intense current drama is not really about the chair of the Fed; this issue with Lisa Cook, a Biden-appointed Fed governor, is more interesting. She was confirmed by the Senate to a 14-year term with the Federal Reserve Board of Governors at the end of 2023, commencing January 2024. That means that if the courts rule Lisa Cook’s termination at the hands of the President was without merit, she will be there another 12+ years. An appeals court has ruled that Lisa Cook’s firing violated the Federal Reserve Act. The decision will likely end up at the Supreme Court, and candidly, it is a jump ball there. I would have said two weeks ago that the odds were very high that the court would uphold the White House decision to terminate her. However, the news this week that the property tax authority in Ann Arbor, Michigan, ruled that she had not broken any laws in declaring her home there as her principal residence while also obtaining permission to rent it out is likely to complicate things. If the Justice Department brings charges against her (they have not yet), and if they obtain a conviction (they have not done so yet), I am certain that the courts will rule the White House had the right to fire her. But right now, it all appears too ambiguous to determine if this clearly pretextual firing will be upheld by the Supreme Court or not.

But that is just one vote. The far bigger issues are not what will happen with one Fed governor. The disparity of “expectations” amongst Fed governors over what to expect just in the next sixty days is massive. And in fairness, “expectations” about the next sixty days are pretty close to reality since the people sharing their expectations are the ones who will be voting on what they expect (I assure you when I say that I “expect” to have Chinese food for dinner tonight, I am the one with the doordash app open on my phone; this is different than when I say I “expect” my favorite team to win a game that I am not playing in). What Fed governors expect out into the future is irrelevant when Fed governors will change their vote in the future based on what circumstances call for at the time. Right now, these dots on the far left for 2025 are, shall we say, close to “pre-votes.”

What you see here is that one Fed governor is saying he sees 1.25% more in cuts by the end of the year – and that Fed governor has been a Fed governor for two whole days now. So yes, Stephen Miran, the Chair of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors, is content to be out on an island by himself at a place where no one believes they will go in two months. Some people interview for jobs very well. Six whole governors said they see no more changes (LOL), and two see one more cut. But, in what matters, nine governors are expecting two more cuts by the end of the year, which is why the fed funds rate presently has an 80% chance in the futures market of ending the year at 3.5% (two more cuts beyond the one done yesterday). This is quite a wide dispersion for only thirty and sixty days and speaks to a real division within the Fed we have not seen before, at a time when the leadership of the lame-duck chair is highly weakened.

What will happen to Lisa Cook? What will happen to Stephen Miran when his term ends? Who will succeed Jerome Powell as Fed chair? And what will it mean for the functionality of our nation’s central bank that some people are digging their feet in, others going way out on a limb, and yet still a sufficient majority is at one particular outcome?

Might I add when it comes to the job interview that is going on like a reality TV show on the national stage (someone should come up with a concept for a reality show where everyone competes for a job with Donald Trump), Christopher Waller and Michelle Bowman, two Trump 1.0 appointments to the Fed who both have seemed quite eager for the Fed chair position next year, each voted for a quarter-point cut this week, leaving just Stephen Miran as the only half-point cut voter. Miran’s odds more than tripled in the Kalshi predictions markets afterwards.

Like sands of the hourglass …

Get Your Holiday Shopping Done Because the New Year is Coming

The entire Fed focus is moving to 2026, and that would be true even if President Trump were not replacing Jay Powell as Fed chair next year. The various pressures in the economy (labor market weakness and tariff-induced vulnerabilities) are very likely to create greater movement for the Fed to play the rescuer it has been asked to play my entire adult life. Beyond the question of who the next Fed chair will be (more on that below), we have a very interesting question in front of us about the fed funds rate in 2026, and other tools within monetary policy.

Let’s start with the obvious question: Why does the Fed dot plot say that the Fed will end up at 3.4% next year, whereas the futures market (real money from real people buying real contracts) says 2.9%? Why does the market not believe what some of the Fed governors are currently saying?

Because markets know best. And they certainly know the real factors driving Fed decisions right now.

Next Fed Chair

Why am I somewhat flippant about this decision when it comes to investment positioning? Because there are four potential candidates, and all four of them are going to do the same thing in 2026 when it comes to the federal funds rate – reduce it. I absolutely have preferences within this list, but whether it is Kevin Hassett (current NEC Director), Kevin Warsh (former Fed governor and Morgan Stanley economist), Stephen Miran (brand new Fed governor and on leave from the CEA), or Christopher Waller (current Fed governor), the rate policy of 2026 will play out the same under any of these four. Do I believe financial markets will respect each of these picks the same? No, I do not. Do I believe that beyond the time frame, President Trump is President, one of these names is preferable to the others? Yes, I do. But I find it very hard to believe that risk assets believe any credible name who is a candidate to be Fed chair next year will be acting differently than any of the others, at least for 2026.

If you are still wondering, my pick is Kevin Warsh. But that is my “pick” – and not my “expectation.” See above for the difference between the two.

Is the Market Going to Overheat?

My friends, a market at 24-25x this year’s earnings and over 22x next year’s [optimistic] earnings is overheated! Will Fed policy cause it to overheat further? Can a lower fed funds rate really bring us to 26x? Is that what investors should want?

I honestly can’t believe I have to even ask those questions.

The fact of the matter is that if the Fed funds rate is brought too low, it may very well keep boosting risk assets, and I wouldn’t dare invest as if that will happen or if I wanted it to happen. And the Fed may lower rates too much because the economy weakens too much, and I am sorry to tell you that if that happen,s it is not going to boost risk assets. And I will not invest as if that will happen, either.

How are most people talking on television about this right now (even if the gist of their comments is not quite as self-aware as I would like)? Essentially, the implicit hope is that somehow, someway, the Fed manages to boost risk assets with a “pro punch bowl” monetary policy that is “just right” – it keeps the partygoer nice and buzzed but not, you know, sloppy. But then, it also assumes that the Fed’s easing is a by-product of a weaker economy that somehow is just a tad weak, and not too weak. Not enough to impact their stocks.

Should the Fed be easing from these levels? Yes

Should the Fed be easing a lot from these levels? Only if you want to set the stage for a rather substantial bubble burst. So, no (sorry if I almost let that question answer itself).

I do not know if the Fed will let an overheated risk asset environment overheat more or not. I do not know how they will respond to certain developments in the months and quarters ahead. I do know that to alter one’s portfolio because they believe the Fed is going to pull off a Houdini miracle is ill-advised.

But I also know that to alter one’s portfolio because we believe we can foresee the exact opposite is, also, ill-advised. This brings me back to the prudent equilibrium I always, always advocate for: A quality-based portfolio defensible as a matter of risk-reward trade-offs, particular financial objectives, tolerance for volatility, cash flow needs, and relevant timelines. When that portfolio has been created, to try to change it because of a hope or a prediction that the Fed will add more booze to the punch bowl when you’re already getting slurry is, well, lacking sober judgment.

Conclusions

The Fed took the necessary step of [belatedly] beginning to remove some excess tightening from monetary policy.

Whether or not they will cut rates to a prudent level and stop remains to be seen.

The economy’s health is not horrid, but it is not clearly robust either. Ambiguity from the labor data and from tariff policy impact leaves real questions.

Risk asset investors can celebrate a modest easing, but should be careful about celebrating (or rooting for) an excess of easing. That excess may not happen, and if it does, many may find themselves wishing they had been more careful in what they wished for.

We have asked the Fed to do something it cannot do. What prudent investors can do is realize this and recognize that their own investment policy ought not be tied to a perfect economic outlook or a perfect prediction about the Fed’s own actions. Somewhere in the bandwidth of outcomes in the jobs data, economic growth, inflation, tariffs, and everything else going on is a properly constructed portfolio.

Do that. In fact, to that end, we work.

Chart of the Week

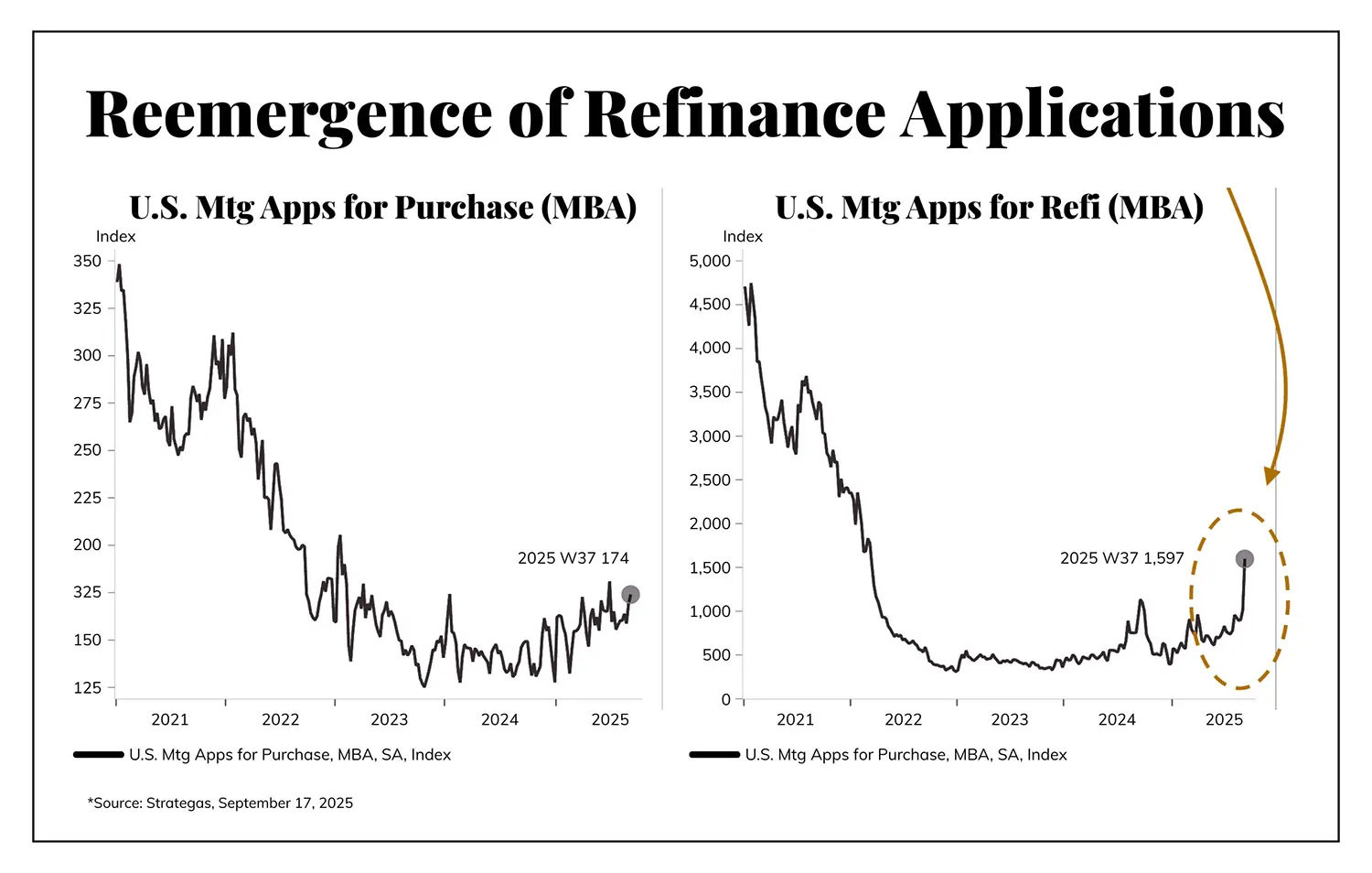

It is going to take a lot less than a 6.26% mortgage rate to get sale activity going again, but just the drop in mortgage rates over the last two months has resulted in a little sign of life with re-finance mortgage applications (undoubtedly from people who bought over the last couple of years at a much higher rate, or those doing cash-out re-finances). It is the chart on the left here that needs to work its way a lot higher.

Quote of the Week

“I think the more absolutely unsubstantiated by anything something is, the longer the craziness can go on.”

~ Cliff Asness

* * *

This went longer than I expected, but there was a lot to say. I welcome your feedback as always and look forward to ongoing coverage of all the Fed fun we will have in the months ahead.

And more than anything else, I look forward to the construction and management of high-quality, dividend-growth, properly-allocated portfolios that do not involve Jay Powell or Stephen Miran as co-portfolio managers. Far more index investors have them as co-PMs than realize they do.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet