Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Today’s Dividend Cafe is sort of the reason the Dividend Cafe started. I didn’t call it Dividend Cafe back then, I didn’t have a website for it, I didn’t post it on social media, it wasn’t re-published on a multitude of financial websites, there was no podcast, there was no video, and it didn’t have nearly 20,000 subscribers. In fact, there couldn’t be any “subscribers” because there was no organized list – just me sending an email from Microsoft Outlook manually to clients I thought would like to hear what I had to say. And the catalyst? A bear market.

The week I began doing this “weekly commentary,” we were not in an “ordinary” bear market. In a ten-day span, Fannie and Freddie had been taken over by the government, Lehman Brothers had declared bankruptcy, AIG had gone down, Merrill Lynch ran into the arms of Bank of America, and my own firm at the time, Morgan Stanley, was in its own existential (but soon to solved) crisis. Mortgage bonds were collapsing, housing prices were utterly collapsing, and yes, the stock market was in freefall.

Today I write to talk about bear markets. Not societal collapse. Not the mother of all credit implosions. Not a deep and unbearable recession (the “great” recession). But bear markets. The kind where stocks drop and investors do one of two things. We are going to talk about those two things, and I hope when you are done reading, you will not merely feel better about this bear market, but even just a little bit excited (as counter-intuitive to human nature as that may be).

So let’s jump on into the Dividend Cafe, as it does what it was always created to do – present the unvarnished truth in matters of macroeconomics and investor behavior, and do so towards the greater end of the very purpose for which we at The Bahnsen Group work.

|

Subscribe on |

Human beings are human

My introduction used the phrase “feeling a little bit excited about the bear market.” I am at a huge risk of sounding insensitive here, and I am totally aware of that. But I am not being insensitive – I am being a truth-teller. Empathetically, I truly do get how tough it is to stomach bear markets. I do get that people see money values at one level, and then at a lower level, and it can challenge their emotional peace of mind. I do not ask people to change their emotions; I ask them to be very careful about acting on their emotions. And if people in my profession do their jobs, yes, investors may end up feeling actually positive about the state of affairs. But that will never be the natural human response; it can only come about if people like me provide the right information, perspective, and truth bombs needed to generate that informed response.

The rules of the game

Why do investors invest in the stock market? Why does one take on the risk of up and down movement in a portfolio when cash savings do not go up and down? The answer is risk premium. The premium return one gets invested in risk assets over time motivates them to invite whatever the “cost” of that premium return may be. Stocks have returned about ~10% per year over the last fifty and one hundred years (as a compounded annual growth rate), where cash has returned closer to 2%. People saving for long-term financial needs not only want the higher return but usually need it.

But I said there was a “cost” to this premium, and there is. There’s No Free Lunch. The cost for equity investors is the reality of volatility – of significant up and down movements around the uncertainty of company earnings, and around the valuation of those earnings. It is entirely manageable and worthwhile (as we shall soon see), but it is a downside “cost” (especially emotionally) to the premium return we want and expect.

Volatility comes from the good stuff

We refer to a P/E ratio as stock investors – that “price” divided by the “earnings” of a company. The “E” can go up and down, and the “ratio” can go up and down. You have two ways to see values go higher (a higher “E”, and a higher “P/E”) – but you have two ways to see values go lower as well.

We don’t buy stocks because we believe the E will go lower. We believe in free enterprise, we believe in the profit motive, we believe in self-interest, we believe in competition, we believe in innovation, we believe in entrepreneurialism, we believe in freedom, we believe in the process of producing goods and services that meet the needs of humanity, and we believe in the human spirit. THAT is the “E” – the earnings – of being an investor in public equities. Some can fail. Some can miscalculate. But diversification solves for that inevitable risk, and the broader aim is achievable through public equity markets.

The “E” is the easier part for a diversified and long-term investor, even though the “E” will have periods of decline and challenge. Companies will underperform, costs will prove higher than expected, customers will respond negatively to a new product, and competition will produce an element of surprise. So there is volatility in the “E” to some degree, but in aggregate, a diversified equity investor rarely sees the “E” across their portfolio decline outside of a broad economic contraction.

The “P-to-E” – the P/E ratio – the multiple – the valuation – now that also impacts stock prices. If a company is generating $10 of profit per share and trading at $100 per share, it has a 10x P/E ratio. But if the same company grows profits to $12 per share, but the P/E ratio goes to 8x, the stock is now $96. So, in that case, a 20% gain in profits led to a 4% decline in stock price. How is that possible? Because the E is one factor, but the P/E is another – and the factors that drive P/E ratios include all sorts of things – interest rates (perhaps the biggest), forward projections, investor sentiment, and so forth.

Separating the two

I care more about the “E” as a portfolio manager than the “P/E” because I believe we can do analysis on the “E” and fundamentally understand a company with a reasonable amount of accuracy, while I believe guessing P/E ratios is far harder than winning in a casino. I believe investing in the “E” is betting on the execution of a given company, and investing in the “P/E” is betting on the madness of crowds. BOTH impact a stock price, but one is far more fundamentally sensible than the other.

What do I mean by the madness of crowds? I mean, sometimes crowds will run a plant-based food products company up to 940 times earnings (a P/E of 940x), and other times that same company will drop -94% in three years. True story.

In a perfect world, P/E ratios can stay within a tight bandwidth and go up or down a little bit based on their comparison to bond yields, or expectations of growth or something, but it is not a perfect world, and valuations get stretched all the time. This will never change. And learning it in the late 1990s as a younger investor and seeing the aftermath in the early 2000s taught me a lot about investing in the momentum of P/E expansion. It is a two-edged sword that has one side I prefer not to touch.

All are exposed

Those engaged in the dangers of speculation or excessive valuation investing are not the only ones exposed to market corrections or bear markets. The beginning of this bear market was mostly taking out the “shiny object” players – the fads, the value-less investments, the real speculative excesses. Much of it was just re-pricing the silliness of believing that what was happening in April of 2020 was ever going to be perfect (by the way, I am sorry our office parking lot has gotten full again; I guess the rest of the world did go back to work again, after all). Much of the carnage earlier in the year were so-called “COVID” stocks getting re-priced to the reality of a non-COVID world. This strikes me as having been an avoidable mistake for investors. But I digress.

But we are not now merely re-pricing excess, or coming to Jesus on the absurdity of NFTs, crypto, plant-based money destruction, and other such Tulips. We are in a bear market. Good companies. Bad companies. In-between. The market is down across all indices.

Why?

The number one biggest reason is higher bond yields. Valuations of stocks get re-priced when comparative bond yields move a lot, and bond yields have moved a lot. Not every time bond yields go up mean stock prices going down. Moderate bond yield increases around the expectations of higher growth can be quite bullish for equities.

But that is not what is happening right now. The 10-year treasury has moved from 1.5% to 3.75% since the beginning of the year. That is sudden, violent, and quite surprising. And it has disrupted lower quality stocks the most, yet higher quality stocks as well (difference in degree but not kind).

But then you get the second-order effect. As rates have come up, already representing a re-pricing and valuation adjustment in markets, then you have the effects of rate changes – lower economic activity, potentially higher unemployment, reduced output, and all the rest. The effects of higher rates then become the cause, after the rates themselves were initially the cause.

Markets right now have a lot to digest, process, and absorb. They do it in the most complex and rapid way imaginable, and they do it taking for granted the aforementioned rules of the game. Long-term investors are not given immunity from the rules.

But what if one needs money?

Up and down movements in a financial asset do not impact the real-life goals of anyone who does not need the money that is going up and down.

Allow me to say that again for the benefit of clients and readers. Up and down movements in a financial asset do not impact the real-life goals of anyone who does not need the money that is going up and down. But what if one needs the money short term? There are two things to be said here.

(1) Principal that is needed within 2, 3, or 5 years ought not to be exposed to the realities of up and down movements. Would you buy a house with money you needed to get to in six months? I would hope not (of course, some did, and then 2008 had to ask them never to do that again). One can speculate if they wish, but we won’t do that at our firm. The timeline for principal access must be correlated to the reality of the asset class, and the reality of stocks is what I have stated above – they are subject to up and down movements.

(2) But alas, some people need the fruit of the tree they have planted – that is, they need INCOME, but not principal. And this is my favorite subject in investing – how dividend growth insulates an income investor (a withdrawer of a stream of capital) from the up and down movements of their investment values, all the while giving them increases in income regardless of the value of the holdings.

Accumulation temptation

For those accumulating assets, not withdrawing, not needing income, it is easy to say “who cares if it goes up and down, you don’t need the money yet, and it will be higher in price when you need it.” All of that may very well be true, and despite the potential insensitivity of it, I suspect it usually is true. But it ignores one other possibility many are allured by – moving in and out of their volatile assets to “game” the system – to avoid the “rules of the game” by wanting to be in the markets when up and out when down.

I won’t re-litigate the case against market timing, per se, here. I will merely make a few points about the laws of the universe that many clever folks forget:

(1) Whatever force may be causing you to think being out at a given time is likely not a force a gazillion others are unaware of. Being bearish can make someone sound smart, but it cannot make them unique.

(2) All points of real market decline notwithstanding, bears live with the upside risk of reality – that is, the fierce and piercing dynamic that is market recovery and market normalcy. Markets drop in bear markets, but the first tranche of their recovery comes so quickly so often that the risk of missing it is asymmetrically dangerous.

(3) Regret then kicks in. And then one is out for even longer. And then they are done. Market timing that missed out on 10% of a 20% drop that now misses out on 85% of a 100% recovery. I cannot tell you how many times I have seen it. And it simply is unacceptable behavior for a disciplined investor.

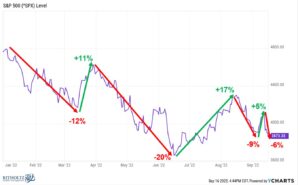

Bear market rallies

The market has not gone straight down this year. It has zigged and zagged, and in the last two weeks, been in a clear zig of downwardness. Bear market rallies happen, too. They only give false hope or false signals to those who are cheating the rules of the game. The zigs and zags, both, are irrelevant. They just are.

History

We are in our 13th bear market since World War II. Thirteen times that the market has dropped -20% or more. The average one lasted a year. The one I started my career with lasted almost three years. The one we all went through with COVID lasted a month.

I do know corporate earnings are up +5,600% since the beginning of these bear markets. And that the market itself is up about 21,000% in that time period. So, yeah. But look, we don’t all have 70-year time horizons, and I get that. So I’ll leave the shock value of the upside math over multiple decades aside.

In one or two bear markets, not merely ten or more, we still have a simple and painful reality for those not acting right … Assets get cheaper than they were and cheaper than they will be.

So why excited?

I believe that in a dividend growth orientation to investing, there are two goals that have to be accounted for, and both are accounted for quite well in a bear market. One is that the accumulator of capital is reinvesting dividends at lower prices, goosing the compounding engine their portfolio represents.

And the other is that the withdrawer of capital is not depleting their principal at lower prices, but protected, and will allow recovery to take hold with all their shares intact, not having had to deplete their capital base for withdrawal needs along the way.

The latter survives and thrives. The former actually benefits from the bear market, and with a better understanding of math and history, roots for more of them.

As crazy as that may be.

Chart of the Week

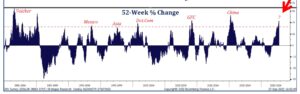

Another reason to be afraid of a potential market reversal to the upside is if you were tempted to cheat bear market rules.

Note the U.S. dollar right now, and note the U.S. dollar in past market disruptions that were attached to big events. Markets can like a strong dollar or a weak dollar in a certain bandwidth, but a strong dollar this strong has historically meant two things: (1) Something bad is happening; and (2) That dollar strength reverts to the mean, sometimes quickly. And when that happens, well, see everything I wrote above about market timing.

*Strategas Research, Technical Strategy Report, Sept. 28, 2022, p. 7

Quote of the Week

“There is a considerable tendency for common stock investors to do the greater part of their buying, both of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ securities, at high levels of the market. They are equally inclined to do the greater part of their selling at low levels of the market, a procedure which is not conducive to successful results.”

~ Benjamin Graham

* * *

Truth be told, I could easily do another 2,000 words on this subject in the next thirty minutes, but I have to get this moving if my team is to have the time to publish today. I love this topic, and I will have more to share in the days and weeks ahead. I do not expect these times to improve quickly. I have “best practices” I can share about managing emotions and temperament through them.

But in the meantime, I am quite sure I am right when I say this – your advisor and all of us at TBG are here for you should you need anything at all. A pep talk. Hand-holding. A reinforcement of your strategy. Discussion of a greater opportunistic approach. General information and education. To all of these ends and more, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet