Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

In this market-shortened week, I thought a shorter Dividend Cafe may be appropriate, especially as we prepare for a long weekend and the Easter holiday. More on that below …

And not only do I think I controlled the length of this week’s Dividend Cafe (within reason), I also took advantage of the week to dive into a topic that is almost entirely avoided by the media and investing public. I can’t really explain why we mostly ignore private equity and private credit when we discuss financial markets. I understand public stock markets have a certain sensationalism to them, not to mention clear pricing visibility that facilitates a lot of noise. But the private markets are just as much the real economy as public markets, and if the heart of free enterprise is where there is human action, I assure you private markets are deep into the capture of human activity (for good or for bad).

But it is not enough to “talk” about private equity and private debt as if they are either “good” or “bad” investments. There is a complexity here that requires a bit of unpacking, and the unpacking of complexity is the business of the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

Why would anyone invest in private investments?

The only reason anyone invests in anything is to earn a return on capital, and so the answer to why one invests in private equity or private debt is because they want to earn a return on their capital. This return can take the form of periodic income (i.e. a stream of interest payments for a private debt investment, on top of the return of capital at the repayment of the debt). It can take the form of a profitable exit (i.e. receiving back more money than you invested when an investment or series of investments are sold). And it can take the form of a hybrid (i.e. dividend or profit receipts for investments along the way to an exit for a higher price than you invested). Of course, if one is receiving a stream of income that they like a lot, they may not want to [even profitably] sell the investment that is creating it, but there are many reasons one may do so (or have to do so).

So the logic of investing in bonds or stocks that have instant liquidity is not altered much when evaluating the rationale for investing in debt or equity that is not liquid. The difference is a “give and take” – and I say give and take – because there is no free lunch.

There is no free … water

The “give” is liquidity – meaning, access to money. So this is easy. If you need instant access to the money you invest, don’t invest in private investments (debt or equity).

But what is the “take”? What does one hope to pick up by giving up liquidity?

The illiquidity premium. And this premium was previously defined as the “extra return required by investors for forfeiting access to their funds. It had mechanical realities to it (i.e. companies may be bought for 8x earnings in the private markets but then sell into public markets for 16x earnings – a sort of financial arbitrage wrapped in illiquidity).

But as I have written over the years, another benefit to the “illiquidity premium” is behavioral. Put as candidly as possible – people are less likely to do stupid things when they can’t do stupid things.

I am sure many people sold really good food and beverage stocks when they shut down our country in March 2020. Those stocks are now up 100%, and much of that recovery came just weeks or months after the shutdown. But the panic sell was enabled by the ability to panic sell.

But what would the “sale value” in March 2020 be for private companies in the food and beverage space? Zero? Something really, really low? I guess we’ll never know, since people couldn’t sell, and normal market conditions returned in time to facilitate a rational valuation.

Private equity controls behavior by eliminating the chance for bad behavior. And there is a premium contained therein.

Sign me up?

But is the mere capacity for illiquidity enough to declare private investments a good idea? What are the risks that have to be understood here in 2022?

What is the impact of rising rates on the asset class?

Are there too many deals out there? Too many fund managers? Too many private companies? Too many transactions? Too many dollars sloshing around?

Do the companies being bought matter? Do the companies doing the buying matter? Are all asset managers the same here? Is it a monolithic space?

Do valuations matter? Does legislation matter? What other macroeconomic or public policy factors may influence the opportunity of private investments?

Let’s briefly unpack these things …

Record Privacy

In 2006 there were $804 billion of global private buyouts (i.e. transactions in the private equity space). In 2020 the number was $577 billion (globally), and then in 2021, the number exploded to $1.1 trillion.

The U.S. also saw its previous high in 2006 (near $200 billion of deal volume), and that number stayed about $200-300 billion per year from 2013-2019. It exploded higher in 2020-2021 as you see below.

But does it matter?

A pretty fair question is – “does high deal volume indicate the end of a cycle?” In other words, is this an indicator of trouble on the horizon in private markets, or in risk assets in general?

It has some logic to it, but I suspect is too simplistic to work as an actionable thesis. First of all, the size of deal flow (dollar volume of transactions) has to be analyzed on an apples-to-apples basis. The size of the public equity markets is a lot larger, and for that matter, so it the size of the economy. The ratio of private markets deal flow relative to public equity capitalization or relative to GDP tells a totally different story than mere absolute dollar levels.

But the other question is: Do mere transactions point to froth? Are we at the end of a cycle of good performance in private market buyouts just because the volume of transactions increased? I would argue that there is a better way to measure these things and that the better way is perhaps more concerning.

Size vs. Valuation

One of the reasons the dollar volume of total private equity deals is higher is because the average size of a deal is higher, and one of the reasons average deal size is higher is because former mid-sized LBO players are now mega-sized LBO players. The top three or four asset managers in the private markets space are now managing a couple trillion dollars amongst them (4-5x what they were even after the financial crisis). Returns have been so strong that capital has not been shy about coming into the space. And massive fundraising has enabled a higher volume of deals, but more so, a higher capitalization target of deals for the mega-cap private equity funds.

None of that concerns me. A very big company is either a good one or it isn’t, and it being big and private no more bothers me than being big and public (and yes, if I had to pick, I could make an argument that being private provides benefits that are surrendered for public companies).

Rationality trumps size. Value creation is the name of this game. Large companies can be under-valued and small companies can be over-valued. Bad operators can ruin good companies and good operators can ruin bad companies. There is no way to avoid the fact that this is a highly idiosyncratic asset class.

Past performance is no predictor, but size and reputation can be

The standard compliance disclaimers about past performance are all true enough, obviously, and many people have learned these things the hard way. But one of the reasons we favor more name-brand private equity managers than “start-ups” is the basic risk mitigation that a track record includes, along with the collective wisdom and culture of a multi-decade operation. Some firms have been buying public companies when interest rates were high and dropping, were low and dropping, were high and rising, and were low and rising. Some have been through recessions and expansions and both sides of the credit cycle. Some have an investor base that adds to their optics in the market and have a multi-asset focus at their firm that gives them private market intelligence from their real estate or peripheral businesses.

Of course, this self-imposed limitation can cause us to miss a real boutique star manager who ends up hitting the ball out of the park on some dynamic private investments. All asset allocators are wise to decide if they are willing to spare some home runs to limit or avoid strikeouts. We made that decision a long, long time ago – and we feel no need to abandon that portfolio commitment in private markets.

Incentives matter

Why do companies pursue the investment of a private markets investor?

Many times they simply need growth capital and private equity becomes the best place to get it.

Some companies are in trouble and need a lifeline (both financially and strategically).

Some are pursuing monetization for their own work and private equity helps them de-risk their own closely-held business without surrendering control.

Some are large enough to cash out in private markets but not large enough to cash out in public markets.

Some need the synergy that a deal in private markets would create (usually another private company merging with them towards the aim of a competitive advantage).

Operators of a business have an incentive to do a private markets deal.

Operators of a business have incentives in what they do within their stewardship of publicly-traded companies.

Operators of a private equity fund have incentives in how they invest and direct the company they have invested in.

And of course, you and I have incentives in the deals we choose to do and why certain [public and private] investments make sense to us.

To invest in private markets without an understanding of the incentives of the actors involved is the biggest danger.

Summary

Yes, hyper-leveraged deals are less attractive when the cost of capital increases due to rising interest rates. Of course, ALL INVESTMENT ASSETS ARE WORTH LESS WHEN THE INTEREST RATE INCREASES. Because math.

Yes, a massive increase of deal flow increases the need for diligence around the quality of deals being done. Are asset managers incentivized to get a volume of deals done, or are they incentivized to get good deals done? Is discipline rewarded or punished in their structure?

Yes, valuations have increased in private markets, and purchase prices are higher making expected returns lower. Is that more true than in comparative public market or real estate investments?

I have witnessed an adult lifetime of real estate investors being able to lie to themselves about what they are doing and what is going on because of illiquidity. Any time there is a lack of mark-to-market mechanism, there is the potential for fantasy thinking. Is one being exposed to fantasy thinking about valuation in private debt or private equity, because they can?

There are investing principles and realities that shape the way we gain access to public markets. If one uses private markets to flee those principles and realities, they are going to get their faces ripped off.

But if one uses private markets to efficiently double down on wise principle and reason, there is a beautiful landscape of opportunity. To that end, we work.

Chart of the Week

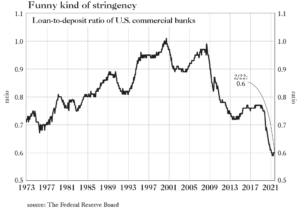

I can only say so often “this is the chart that tells it all” before people stop believing that the charts I post say anything at all. And indeed, I have shown charts of collapsing velocity, as well as collapsing marginal revenue product of debt, that have caused me to previously say, “this says it all!”

But I am not sure this chart is any different than those … In other words, what this “tells it all” chart points to is directly correlated to velocity, and marginal revenue product, and that is – the combined deflationary forces that have weighed on economic growth for so, so long. Here it is simply the evidence of it in the banking system. The misnomer that greater DEPOSITS in the banking system create inflation is part of the problem – it is LOANS that actually had new money in circulation. But then a collapsing ratio of loans relative to deposits does not CREATE deflationary pressures; it ILLUMINATES them. And what we see here is a profound visualization of the diminishing opportunity set in using monetary policy to drive economic growth. Would-be economic actors cannot be forced to borrow money just because capital is cheap. Bad borrowers can receive cheaper financing (distorting the cost of risk in the economy), but good borrowers and good projects to borrow for are not created ex nihilo.

Quote of the Week

“Who steals my purse steals trash … but he that filches from me my good name, robs me of that which not enriches him, and makes me poor indeed.”

~ William Shakespeare

* * *

May you all enjoy “Good Friday” and the extra weekend day it represents this weekend. And may you all have a truly Happy Easter. History has never been the same.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet