Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

“Sell in May and go away” became an adage some people love to say in our business, and I really have no idea where it came from. Whenever people ask me if we follow that adage I reply the same as I do about any other “adage” – things that are made up to offer a cute rhyme may not necessarily be the best way to formulate an investment policy.

Some months, markets go down. Some months, really good investment plans see the holdings in a portfolio increase in price, and other times, they decrease in price. The investment plan is not better or worse in some months than the others—it is all part of the plan, presumably put together.

Various calendar correlations, almanac tidbits, and nursery rhyme poetry are not investment strategies. They are actually not even good at understanding correlations, let alone causations, as most of these things on their own merits and claims are merely 50/50 propositions.

But a real investable philosophy is what you can find in the pages of Dividend Cafe. And for a discussion of all those things and more, we start … now …

|

Subscribe on |

Inconvenient truth

The hardest thing for a certain camp of people to explain in the current moment, and I suspect for a long time to come, is why, in the U.S. inflation moment of 2022 and throughout the two years since the U.S. dollar has continually strengthened? It simply is not consistent with the message that we are constantly being fed – that U.S. inflation is a by-product of all the policy decisions of 2020-2022 versus the supply chain shutdowns (and labor shortages transfer payments and extended unemployment compensation exacerbated). There was certainly fiscal and monetary sugar high in the system, but when countries flood their citizens with funny money the exchange rate is supposed to plummet (I can offer examples beyond Nigeria, Argentina, and Zimbabwe if you’d like). The dollar has RALLIED, and demand from foreign actors for dollars has INTENSIFIED. That, my friends, is not inflation.

Are there explanations as to why we’d have price increases and, at the same time, a strengthening currency? Sure there are. And some may disagree with my own assessment of it (which is certainly fine by me). But the fact that a large portion of the price increases were global in nature, mirrored in countries that had nowhere near the fiscal and monetary response we did, reinforces the supply-side theory of the case I have long advocated. But as for the dollar, at the end of the day the world has continued to vote with its own financial actions that the dollar was the better hold.

While I remain as critical as anyone could be of the parts of monetary policy that matter to me (see next section), the fact of the matter is that the Federal Reserve is deemed to have exponentially more credibility than its vast set of central banking peers across the globe.

What are those monetary criticisms?

(1) The Fed ought not be setting the cost of capital when lenders and borrowers can do so

(2) The Fed ought to have more rules and less discretion when it comes to policy objectives

(3) The Fed should not operate out of a Phillips Curve model that presupposes employment and price stability are at odds with one another

(4) The Fed should not be viewed (or operate) as the chief responsible body in charge of the U.S. economy

Speaking of the Fed

So by now everyone knows the Fed did not raise rates this week (that was never on the table), they did not cut rates this week (that has been off the table for at least a month), and they did not signal any re-thinking about raising rates in the future (my view has been they are not going to do so, and Powell essentially reiterated that this week). What they did announce was that they were slowing the amount of quantitative tightening from $60 billion/month to $25 billion/month. This quantitative tightening cessation was a theme of ours this year, and while this is only one incremental step towards cessation, and possibly eventual reversal back into easing, it speaks loudly to the situation the Fed is in.

Why would the Fed say, “We can’t cut rates yet until we see more downward pressure on inflation,” and then turn around and “ease” policy with a reduction of quantitative tightening? I have three theories, and to be honest, I believe all three at once:

- The interest rate is too heavily watched and understood to visibly mess with that before they get more cosmetic support for lower inflation. The dynamics of quantitative easing and tightening are watched by almost no one (besides super cool, handsome, physically fit financial professionals) and understood by even less.

- Reducing quantitative tightening is not inflationary. Quantitative easing, as a mechanism of putting money into the banking system’s excess reserves, is not inflationary, so reducing the level of tightening is not inflationary, either.

- Slowing the pace of tightening is still tightening. “Less tight” is not “easing”. They are, for now, reducing $25 billion from the balance sheet every month. This is directional tightness, no matter how you cut it.

Volatility is how you look at it?

It seems to many that volatility has picked up quite a bit this year (another theme of ours this year), with big rallies in Q1 big sell-offs in April, and lots of zigs and zags of uncertainty as to where markets stand. Fair enough, and day-to-day moves have picked up a bit, a theme of ours coming into 2024. But it is also noteworthy, that the S&P 500 has not had a down -2% day in over a year, getting close to 2017 records for subdued downside vol. Look, maybe -1.5% days don’t feel any different to you than -2% days, and candidly, none of them should mean a thing to anyone investing like an adult. But for all the enhanced responsiveness around Jay Powell and CPI, it hasn’t led to even a 2% down day in a long, long time. I am old enough to remember spring 2020, when down -2% days sometimes felt like the calm ones!

Economic Growth is a Global Convo

We know that U.S. real GDP growth came in at +1.6% for Q1. What has not been discussed is the +2.2% figure for global growth. On one hand, global growth below U.S. growth has not been the norm for the last 25 years, but on the other hand, global growth was +1.7% in Q4. The sentiment is not good in Germany or China but has picked up in the United Kingdom, South Korea, and Brazil and is downright strong in Malaysia. Also of note – significant upward revisions in Argentina … (now what has been going on there?? #letfreedomring)

Growth vs. Value and the underlying premise

Earnings-per-share growth of that which is indexed or compartmentalized as “growth” has been +5.9% per year for the last fifty years. But earnings-per-share growth for “value” has been 5.4%. A massive valuation premium (an average of a 25% premium in valuation, and right now a 40% premium), for what has been 50 basis points of additional earnings growth? Ay yi yi.

Small Cap Day in the Sun

There was a 10-year period, once, where small cap outperformed large cap, but a 10-year period like this of large cap outperforming small cap? Hasn’t happened. The small cap/large cap trade-off has generally been 5-7-year cycles. Look, these things can vacillate and change and there is simply no scientific law as to what they are supposed to do. And if you think I am down on large-cap indexing, you should hear what I think about small-cap indexing … BUT, the discount of small-cap valuation to large-cap valuation is currently very close to 50%, and that is simply unsustainable. Small-cap stocks have also averaged 8% of the total U.S. stock market capitalization and are currently 4%. Asset allocators should be paying attention, but doing it from a bottom-up perspective.

You Run It. No, You Run It. I don’t want to run it, you run it

773 major corporate pension plans were turned over to gigantic insurance companies last year. 568 were turned over the year before. What is going on here? Companies do not want to manage the assets and they don’t want to keep the liabilities. Insurance companies do want to manage the assets and are willing to pay the companies for the combined assets and liabilities (at a slight discount to the presumed asset/liability value). One party gets what they want and thinks they do well, and the other party gets it all off their books. $135 billion of pension liabilities have moved to insurance companies in the last three years alone.

An annuity (insurance contract) replacing company paternalism – a good trade-off, if you ask me. Now, these pensions then lose PBGC coverage but gain A-rated insurance companies with their own regulatory capital and credit parameters. Why would any pensioner want a BBB-rated company guaranteeing their pension when an A+ level insurer is willing to do so?

But to me, the biggest issue (and I say this as a positive) is that so many large private equity companies (these days, multi-asset alternative managers is a better way to describe them) have acquired these insurance companies, expanding the asset management talent, deal flow, and investment sophistication significantly, all the while maintaining the capital standards and regulatory checks as mainline insurance companies.

Growth catalysts

If there were to be a catalyst to economic growth in the next year or two that lifts real GDP growth above the subpar level, what would it be? A few worthy considerations:

Inventories are low and new orders are picking up, suggesting that many of those new factories recently constructed may soon see a needed increase in output. Manufacturing has shown some signs of light lately, and the general capex-productivity theme has continued to stay promising for several quarters now.

Some have said the “wealth effect” is a catalyst to growth—that high home prices and stock values will keep driving consumption activity. I find this whole theme poppycock and always have. I also think I deserve credit for using the word “poppycock” even though I am a relatively young man, not quite 50.

Fed dovishness is not a catalyst for growth. If the Fed ends up being dovish (IF), it may boost asset prices, but it can’t generate sustainable organic growth on its own.

Of course, technology advancements that boost productivity are always on the table, and you may have heard many believe artificial intelligence will help facilitate some of that. I hope they are right. The actual may take time to catch up to the hype.

The bottom line is that economic growth has been suppressed for a long time by financial repression, excessive government debt, a decline in productivity, misallocation of capital and resources post-GFC, and marginalized capex and capital investment. All these aforementioned issues have been created. Should there be productive investment in productive projects then, yes, we could see a catalyst to better-than-we-have-had intermediate growth. That remains the best theory of the case, in our view.

A belated tribute

Many have written better tributes to Daniel Kahneman than I am capable of writing over the last month or so. But as one who has devoted much of his life to behavioral economics and whose career is almost entirely intertwined with the reality of human psychology applied to financial decision-making, I have to make a comment about the Nobel-winning genius who profoundly informed our understanding of fundamental investor mentality. I could make this a very elaborate or detailed paragraph, but truth be told, it can be summarized quite easily: Investors hate losses more than they love gains. It isn’t rocket science. Loss aversion drives decision-making, and that is true even when the investor doesn’t realize it, themselves. And to make matters worse, the behavioral response out of loss aversion generally comes after the negative event, not in front of it.

The insistence we have on proper portfolio construction is largely informed by Kahneman’s observations – loss aversion snowballs to worse behavior. Investors can say that all they want to know is “how much am I up?” (or to a hot manager, “how much were you up last year?”), but in the end, “being down” drives poor decisions because of human emotions that then jeopardize what the answer will be to “How much am I up?” Nothing hurts how much people are up, then what they do when they are down.

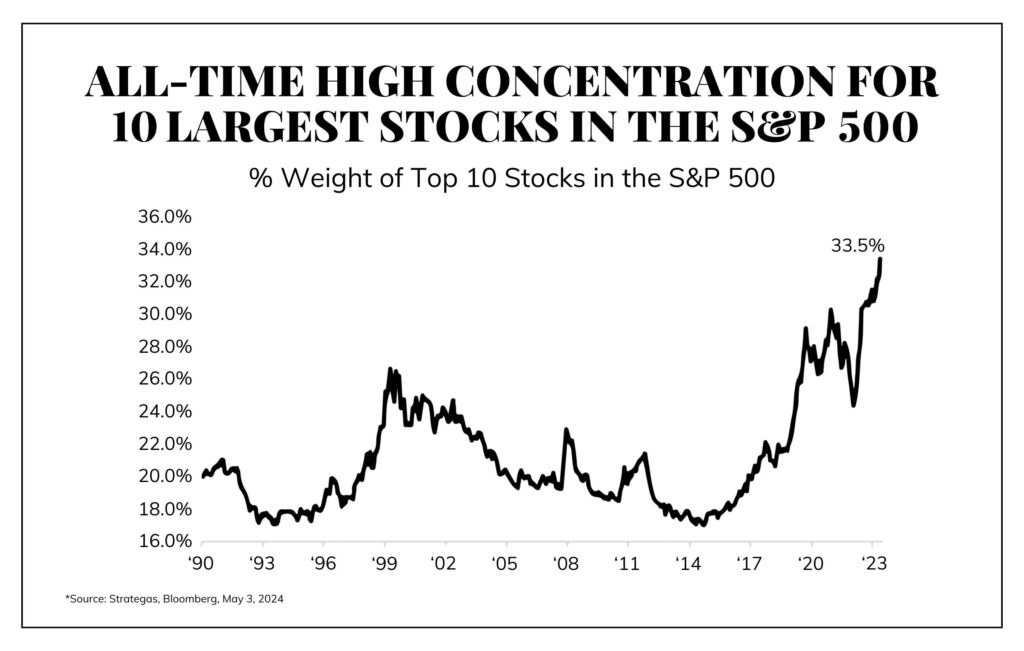

Chart of the Week

This chart doesn’t need any commentary from me.

Quote of the Week

“Only fools, liars, and charlatans predict earthquakes.”

~ Charles Richter

* * *

May is here and we’re sticking with what we believe. As adorable as 7-month plans, or 9-month plans, or 11-month plans may be, we are focused on 12-month plans that are a part of multi-decade plans at our firm. Some may say we take a #fulltime approach to this … To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet