Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Before we dive into this week’s Dividend Cafe, I first wanted to take advantage of this moment to hype our pending SPECIAL EDITION ELECTION ISSUE of the Dividend Cafe. At this point, I will commit to that coming out two weeks from today (Sept. 27) in the Dividend Cafe.

The intent will be to produce an extensive commentary on as many ramifications for investors as I can come up with regarding the November election, from outlook to perspective to commentary, to sector attention, to history, to so much more. It will not be partisan, it will not reflect my own wishes (none of you want to know what I actually wish for in this year’s election), and it will not be offensive to anyone (okay, I obviously can’t make promises on that last part because these days I find that the most benign of statements may end up being offensive to someone, but what I can say is that there will be nothing which should offend anyone).

Mark your calendars for the Sept. 27 SPECIAL EDITION ELECTION ISSUE of the Dividend Cafe.

In the meantime, this week’s Dividend Cafe is worth your click and attention. Too many investors think the wrong way about something, and too many money managers are very happy to let them think the wrong way as long as they keep getting paid. I think you will find some of the information this week on the market, on manager conviction, on housing and culture, and even on immigrant employment, to be, well, worth the price of admission.

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe!

|

Subscribe on |

Moral authority and conviction

I attended a meeting on Thursday this week in midtown Manhattan with one of our portfolio managers. I really do believe him to be one of the smartest growth managers on the planet. While we use him only in our Growth Enhancement portfolio sleeve, where he oversees a dedicated emerging markets strategy, he and his firm run many billions of dollars in other growth strategies covering all global markets (U.S. and developed international, in addition to the emerging markets we use). He has recently curtailed his exposure to U.S. technology companies a great deal, resulting in a significant underweight to technology relative to index benchmarks. In our discussion with a small circle of other portfolio managers and investment professionals Thursday afternoon, the following question was posed:

With technology such a large weighting in the S&P 500, it seems that if you own it at the same proportion to the S&P and it drops, you just drop in tandem with the benchmark, and everyone will forgive you; but if you don’t own it or have a big underweight, and it continues to rally higher, it seems investors will not forgive you for not owning it. How can you outperform your benchmark by not owning what is such a high weighting in the index?

I could have cried upon hearing the reply (to paraphrase):

That is why people under-perform. Everybody is afraid to act on their own conviction and have their own point of view. Managing to career risk has resulted in an active management industry full of closet indexers that charge a lot more than index funds do. You only ‘outperform’ when you act on your convictions, and if the risk that comes with that is uncomfortable for some, I do not care.

All at once, there is a great moral authority in what he is saying: The pragmatics that justify closet-indexing from a career standpoint can never morally rationalize doing what one does not believe in or not doing what one does believe in. If this sounds familiar to you, it’s because it should be. But there is also a profound mathematical truth to what he has said. The person asking the question apparently couldn’t appreciate the irony of his question’s premise. He essentially asked, “How do you expect to outperform if you don’t do what everyone else is doing?” Like the famous factoid of 90% of people in every room believing themselves to be of “above average” intelligence, there is an internal contradiction in saying that one may not outperform if they do not exactly perform in line.

Every investor has different goals, objectives, and needs. Every manager employed in the pursuit of managing capital towards the goals, objectives, and needs of investors has different mandates, burdens, and criteria by which they want to be judged. I may disagree with the objective of passivity, but I do know a way to achieve it if that were the objective. It may turn out that an underweight on technology or an overweight on technology is a smart thing, but I do know that the way to act on one’s convictions about that topic is not to wonder, “What will make clients more mad?”

Fiduciaries do what they believe is right, and they tell the truth. To that end, we work.

Concentration reality

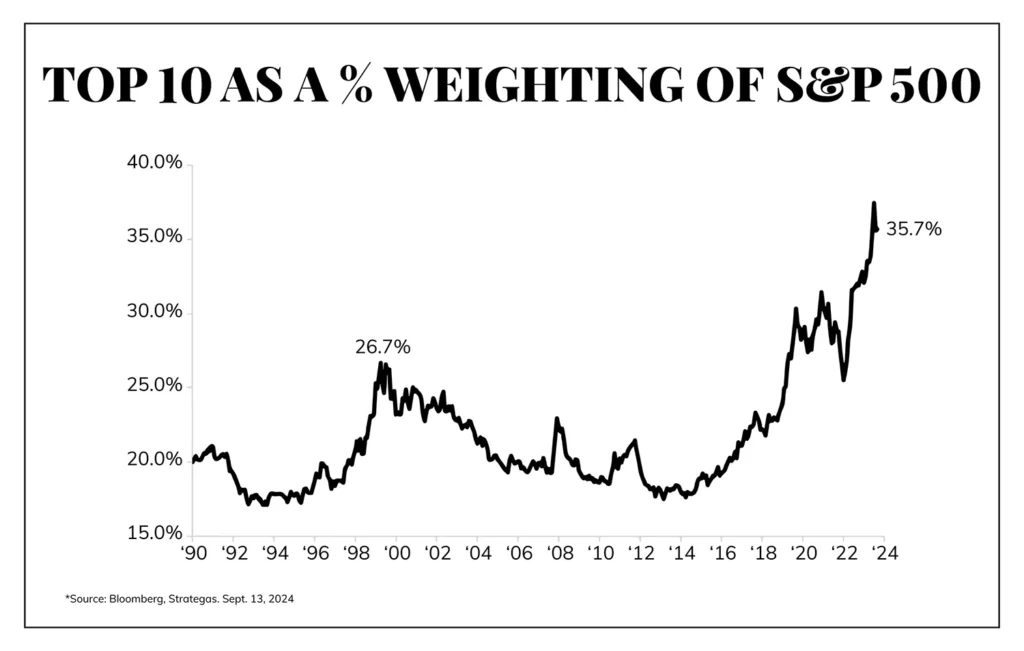

Ten companies in the S&P 500 are 36% of the index right now (2% = 36%, yep). So for those who think the purpose in managing money is to tell your clients that you “beat” the S&P 500, you have three ways to do this in such a circumstance:

- Make your exposure to those ten companies much higher than 36% and hope they go higher at a rate above the growth rate of the rest of the S&P 500

- Make your exposure to those ten companies much lower than 36% and hope they go down (or at least go up much less than the rest of the S&P 500)

- Have a 36% weighting in those ten companies, and then have 64% of your portfolio so different from (and so superior to) the rest of the S&P 500 that you do well

One can see from the testimony of history where ten companies have essentially averaged 20% of the index, not 36%, that one’s weightings of those ten companies were much less important when it comes to “out-performance” than it is now. At this weighting, your choice to over-allocate here or under-allocate here and how these ten names do are essentially going to determine the “relative” outcome mathematically.

But I have a question. Am I seriously supposed to care about this? Does this really matter to any actual person in a given quarter or given year? Does someone really serve their clients by saying, “I am going to FIFTY PERCENT weighting to a few big tech companies because I am determined to outperform a market that has 36% weighting?” Does that sound smart to you? Does it sound prudent or responsible?

What about an approach like this?

“I believe in dividend-growing companies that will sustainably grow their dividends over time, and believe that some years things like popularity and size will do better than cash flow, profits, and value, and over time I believe cash flow, profits, and value will deliver the outcome I am committed to for clients. The raindrop race along the way runs counter to my fiduciary duty, and I will not be sucked into it by a culture that has lost its mind in so many ways besides this.”

I may need to update our mission statement.

Facts in evidence

I saw the following five points listed as a summary of an investment report I read earlier in the week:

- Tech stocks are in technical trouble.

- Tech flows/positioning reached an extreme.

- Tech stock valuations are extremely expensive.

- Rotation opportunities are gaining traction.

- Recession risk is rising.

I would add this chart to the mix:

*CNBC – September 13, 2024

The two-year treasury bond has rallied like crazy the last six months, as yields have dropped from 5% to 3.5% – a violent drop that doesn’t exactly scream “economic growth.” Considering that the Fed Funds rate remains at 5.5% (for another few days), it is also screaming, “Fed, cut rates, now!”

But all of these five points have to be taken in tandem. I do not believe a recession is coming, even as I buy the economic slowing narrative. But that tech valuations are extreme even as flows have been extreme, and now both technicals and fundamentals are vulnerable is all indisputable and all problematic. See the aforementioned sections in this commentary for how we recommend addressing this.

Only sort of a housing problem

When the silent generation turned thirty years old, 55% of them owned homes. When baby boomers turned thirty, 48% of them owned homes. When my own Gen X turned thirty, 42% owned homes. Today, 33% of thirty-year-olds own homes – a new low. (h/t Apartment List Report, Peter Boockvar). Now, as much as I am confident this is a statement about home affordability, it must be said that it also is a cultural commentary, as well. The silent generation were all adults at age 19; today we give people a ten-year pass after college to “find themselves” (I kid, I kid, sort of). The entire life cycle of young adults is different now (marriage, kids, career, etc.), and naturally, that alters the economic decision-making involved in a home purchase. This is a classic example of the nexus that most motivates me – culture and economics feeding off of each other in human formation – for good or for bad.

Always more than meets the eye

Many of my friends have made a lot of noise around the labor data showing a disproportionately high number of NET new jobs in the past couple of years being held by foreign-born versus native Americans. Some suggest, perhaps with prima facie support, that this indicates a job market where only immigrants (and maybe even illegal ones at that) are finding jobs in this economy. I am all for trying to find political hot takes wherever it will grow someone’s Twitter followers (okay, I am not really all for that), but this is actually not a good take upon further reflection.

The problem with this narrative about immigrants in the jobs data (and I have studied this very, very thoroughly) is that it ignores the PRIMARY numerical factor:

Baby-boomers retiring

Nearly all retirees right now are essentially NATIVE (there were very, very few immigrants coming in 1946-1964). So now those of retirement age are disproportionately native-born, so as they leave the workforce, it increases the proportion of new jobs for those who were foreign-born. In a nation of 44 million legal immigrants where very few are leaving the workforce, but native-born boomers are retiring en masse, it is logical that the data would skew towards a high foreign-born net new job creation without really saying anything about the current immigration crisis.

I know this is not the narrative many want to hear right now, but I am convinced it is the truthful one. I may be a bad messenger here …

Chart of the Week

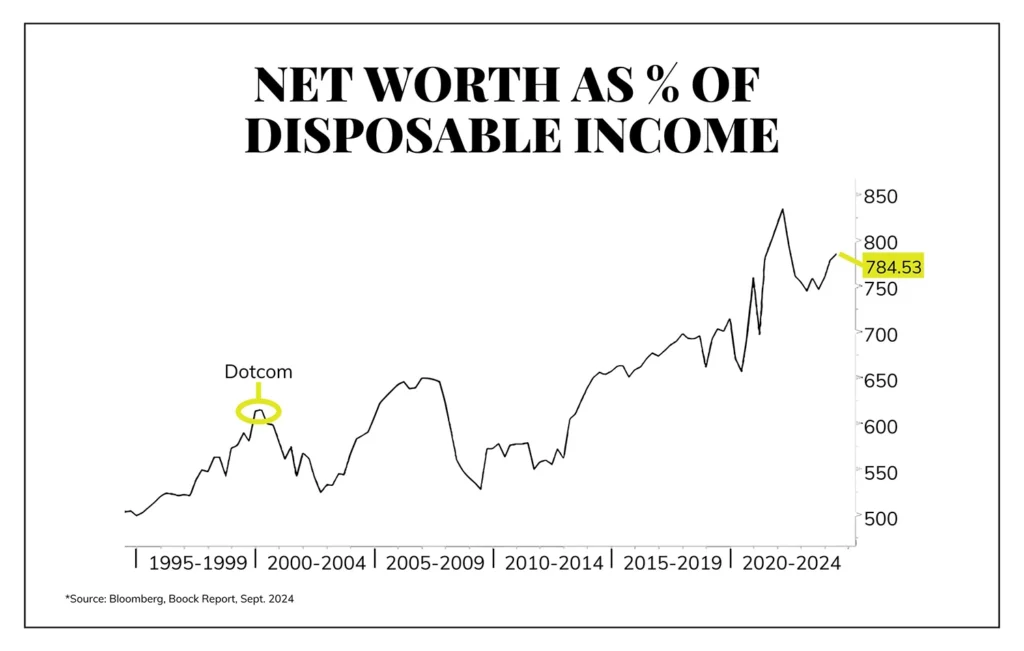

American household net worth got to be 614% of disposable personal income at the dot-com peak in March 2000 (stock prices were way up; housing prices were okay). It hit 650% in 2006 when housing prices hit their pre-crisis peak, and stock prices had been appreciating for four straight years. It obviously collapsed during the GFC as both housing and stock prices collapsed. It hit an all-time high of 850% when shiny objects, stocks, and house prices were all at astronomical levels. It now sits at 785%, lower than 2022 because income has risen over the last two years while house prices have leveled and shiny objects got cleaned out two years ago – so not at the level of 2022, but well above historical averages. Is this predictive? Not necessarily. But it is interesting. Net worth grows more than income when asset prices are growing.

Quote of the Week

“You never see further than your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

—E.L. Doctorow

* * *

USC has a bye week this week before a big test in Ann Arbor, Michigan next week. My beloved Cowboys started strong as the NFL kicked off last week and have a fun game themselves this weekend. It’s a beautiful fall (still warm) weekend here in Manhattan. And God is good to me. Thank you all for your trust (clients) and attention (readers), and have a wonderful football-filled weekend, yourselves!

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet