Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

There is no shortage of investment symposiums to attend in my business. Whether it be events put on by the big firms I have worked for over the years (UBS, Morgan Stanley), or symposiums sponsored by various money managers and asset management firms, or just independent groups putting on their own show, I am quite sure I have attended over a hundred such events in the last two decades or so, and probably spoken at a couple of dozen myself. While there is always something to be learned at every event, some are surely better than others. The quality of the events, the quality of the speakers, and the candor of the speakers in the message they deliver can vary a great deal.

I consider myself an incorrigible consumer of information and perspective and have been obsessed with growing my capacity for investment and economic thought since the turn of the century. These events can be a waste, or they can be utterly thought-provoking or somewhere in between. One develops an instinct over the years for which events and organizations and speakers will be worthwhile and which will not. And this brings me to the subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe …

Before I unpack what I am talking about and why you should care, I just want to say that this week’s Dividend Cafe is basically about the three most important things happening in global economics right now. One is of short-term concern to people, one is more intermediate, and one is longer-term. This is not an “industry report” about a conference – this is a practical, actionable, investor-focused Dividend Cafe on the major things on my mind right now. Yes, I am using a conference to tee it up, but dive into the Dividend Cafe for what may just be the most interesting set of topics I have addressed in a long time.

I have already revealed where I am going with this the last couple of weeks, so there’s no need to hide the ball. The Mauldin Strategic Investment Conference took place (virtually) in mid-May, and it most certainly represents one of the truly spectacular conferences I have ever been a part of in terms of content, speaker quality, and diversity of thought. I chose to turn my major takeaways from the conference into a Dividend Cafe because I basically think Dividend Cafe exists for me to share what is most on my mind with our clients … And I assure you these takeaways from the conference are what is taking up most of my headspace these days.

The bad kind of diversity

But let me first explain an earlier comment. “Diversity of thought” is not always a great thing, even if it is generally uttered to always sound like a great thing. There are always points of view that are essentially imbecilic and lacking prima facie credibility when it comes to a given topic. There are points of view that are conflicted and even corrupt. There are also points of view that lack epistemological self-awareness (if you don’t like that vocabulary, blame my dad) – meaning people who are promoting a certain view without any understanding of the actual premises and foundation that underlie it. There are fringe views that constitute a certain radicalism that often is not worthy of shelf space. With scarce real estate, one has to be choosy.

The classical liberal appreciation for pluralism is a good thing, but it can be taken too far. Diversity of thought does not have to mean “universally exhaustive.” But my view has always been that I learn a great deal about what I believe and why I believe it from studying and understanding opposing or contrary views. Any serious student of ideas will drink from a diverse well of perspectives.

The genius of the Mauldin SIC is that there are limits and barriers for who gets a microphone (fringe/radical views don’t seem to me to be represented at the conference), and present company excluded; there is a real barrier to entry for the credibility, gravitas, reputation, and capacity of those speaking. And yet, in that selectivity and selection, there is a real diversification in point of view that is absolutely invigorating intellectually. The conference almost forces you to re-think your assumptions on many issues and to wrestle with various ideas (since so many speakers and panels are, themselves, wrestling with each other).

This year’s conference featured well-known market bears, well-known market bulls, and a variety of positions in-between. It featured inflation fears, deflation fears, and a hybrid of both. There were China doves, China hawks, and China “can’t put me in a box.” This particular conference did not exist to convince the attendees of a given house point of view. It almost existed to make people with strongly-held views re-consider them.

I also was introduced to new subjects where I had no pre-conceived thoughts or leanings. Some of these things have provoked me a great deal and have not yet been resolved. I’ll share what all this looks like to the best of my ability.

Live from [wherever] …

My final introductory comment is that I do hope and pray the conference will be live and in-person next year. Hearing Louie Gave speak on my computer screen about the strength of the Chinese renminbi is one thing; sitting down in the hotel lounge and talking shop is another. The “supplemental” conversations that take place at these events are the parts that a virtual format can’t replace. And while Zoom and Teams and Skype and all the digital tools that have gotten us through the lockdowns have served their purpose, I am at the top of the list of folks eager to resume using such tools “only as a last resort.” Normalcy means live events. And normalcy is coming.

(To that end, we will be hosting our normal client events in California and New York later this year, with myself and Larry Kudlow speaking at both; more info to come in the months ahead).

Categories for Discussion

I have pages and pages of notes, slide decks, outlines, and takeaways from the conference, but not only would it be drinking from a firehose for you if I “dumped” all that on you, but it would also be the same for me to try and organize it that way. To make this as easy a read as possible, I am going to divide this into three categories or topics:

(1) Inflation/Deflation Redux

(2) China

(3) The Fed

There will be some supplemental odds and ends to close us out. Here we go.

Did a speaker guess the market’s direction?

Okay. Let’s talk markets. The bull vs. bear debates are not especially new, and I think Dividend Cafe readers know where I stand in these things. I am pretty much always market-agnostic in the short term, and that view comes from the humility of history and its punishing posture on those who dare to take high conviction views about what the market is about to do. Those who are sure the markets “look good” for “smooth sailing” in the near term will often get their faces ripped off. And God knows those who are “just sure” that “markets are headed for real turmoil” have become the classic broken clocks of our business. I don’t go into either camp because I think both camps have almost no chance of being sustainably correct, are dependent on unreliable conjecture, and candidly spend most of their time explaining why their last prediction was wrong versus why their next prediction will be right. My view is that investors are better served by short-term market movements not mattering to their portfolio than foolishly trying to speculate what those movements will be.

The advantage to hearing some credible market bears like David Rosenberg is not, for me, formulating a short-term market viewpoint (it is worth noting that David was really, really bearish on markets a year ago, about 10,000 Dow points ago). Rather, the advantage is the data and economic backdrop he brings to his work. I have no interest in applying these things to “what the market will do next month.” Still, I do benefit from seeing how bank lending remains brutally depressed (classic deflation), where Americans spent vs. saved their stimulus checks and the state of wages within all the labor data. This is a great example of where one can learn from the premises of someone whose conclusions they disagree with.

The talk about where the market is going from here is good banter at a conference. It is almost intolerable in the media, but in no context is it a good investment policy. But the various arguments on both sides of the inflation/deflation debate are invaluable in formulating a longer-term investment approach.

Inflation Camp

The major points of the pro-inflation crowd are not necessarily surprising, but they are quite thorough and well-presented. Peter Boockvar pointed out that Services Inflation (ex-energy) was already up 2.8% per annum for five years pre-COVID – that it was just goods inflation that was holding such data back.

*Boock Report, Mauldin SIC, May 2021

Peter believes the disinflation in Services from COVID will wear off, and inflation will resume there, only this time with goods prices inflating as well. He points out the various places where core goods are seeing price inflation now, and he uses the dry Baltic index and shipping/container costs and food prices and used car prices, etc., to make his point. Indeed, his data comes not from one or two anecdotal categories but rather a plethora of reinforcing areas and economic data points.

The challenge with the various inflation arguments is that none of them are necessarily inconsistent, with those who believe some of these forces will prove transitory. Pointing out that lumber prices or copper prices are higher now, even after adjusting for base effect, does not solve for whether or not these price increases will prove “sticky.” Peter believes it is wages that will see price inflation and that those will prove “sticky,” ergo, inflation. It is an unfair burden to Peter to expect him to “prove” what will happen, but he certainly made a compelling case for what is currently happening, and he doesn’t lack conviction in his case for its sustainability.

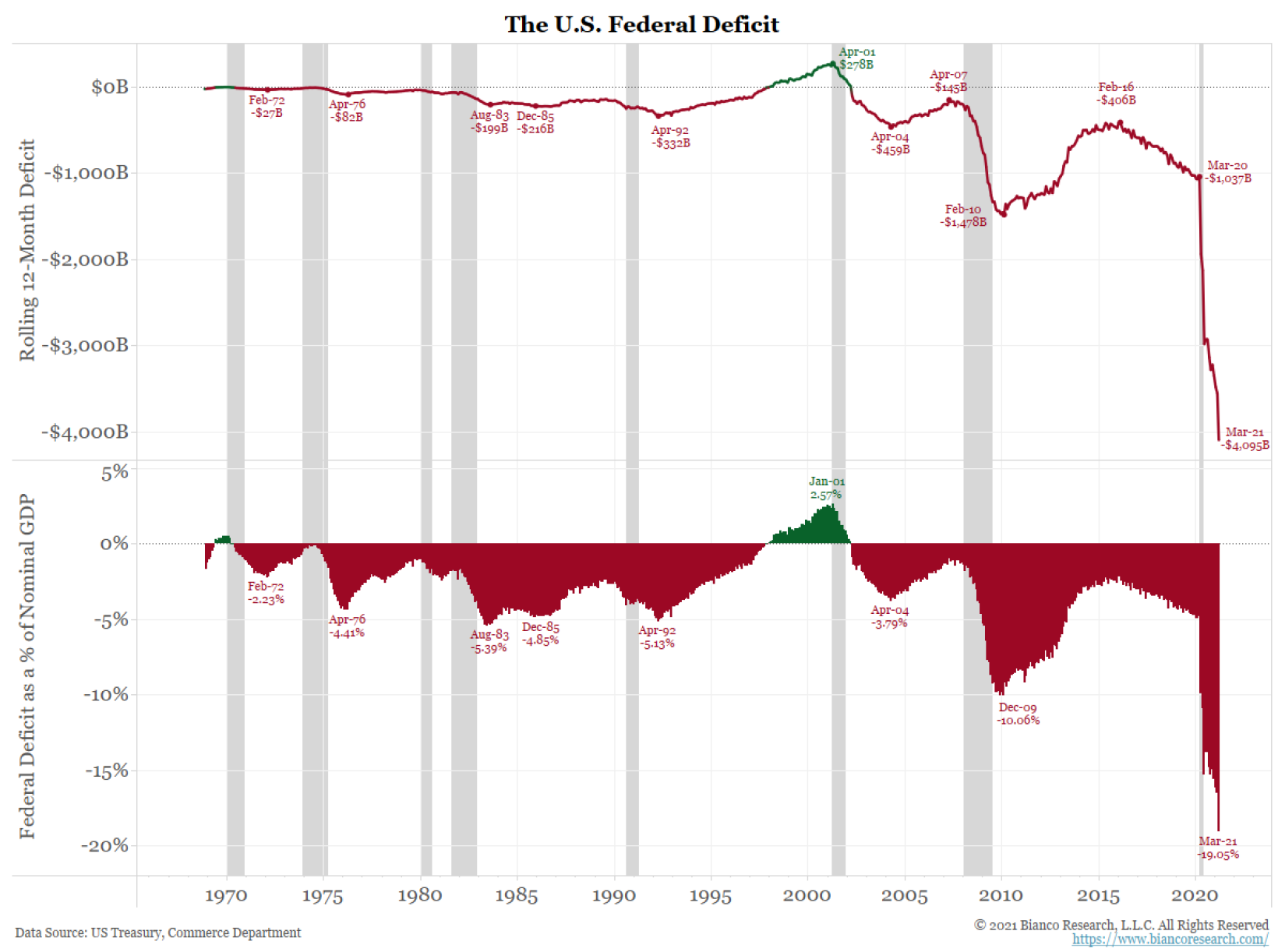

Jim Bianco is an interesting case because he is a long-time proponent that the over-arching pressure has been deflationary and yet has reversed his outlook as of late to the more inflationary camp. He also cites commodity price increases and CPI forecasts to make his case and provided one of the ugliest graphic illustrations of deficit spending that I have ever seen:

Boiling it down

Again, the empirical support for how a plethora of economic data reflects cyclical inflation right now is overwhelming. The arguments that much of these dynamics reflect base effect (prices recovering from distressed levels), and/or supply chain disruptions (prices move higher when goods manufacturing is constrained), are not disproven by these data points; it just leaves the heart of the matter TBD.

And what is the heart of the matter?

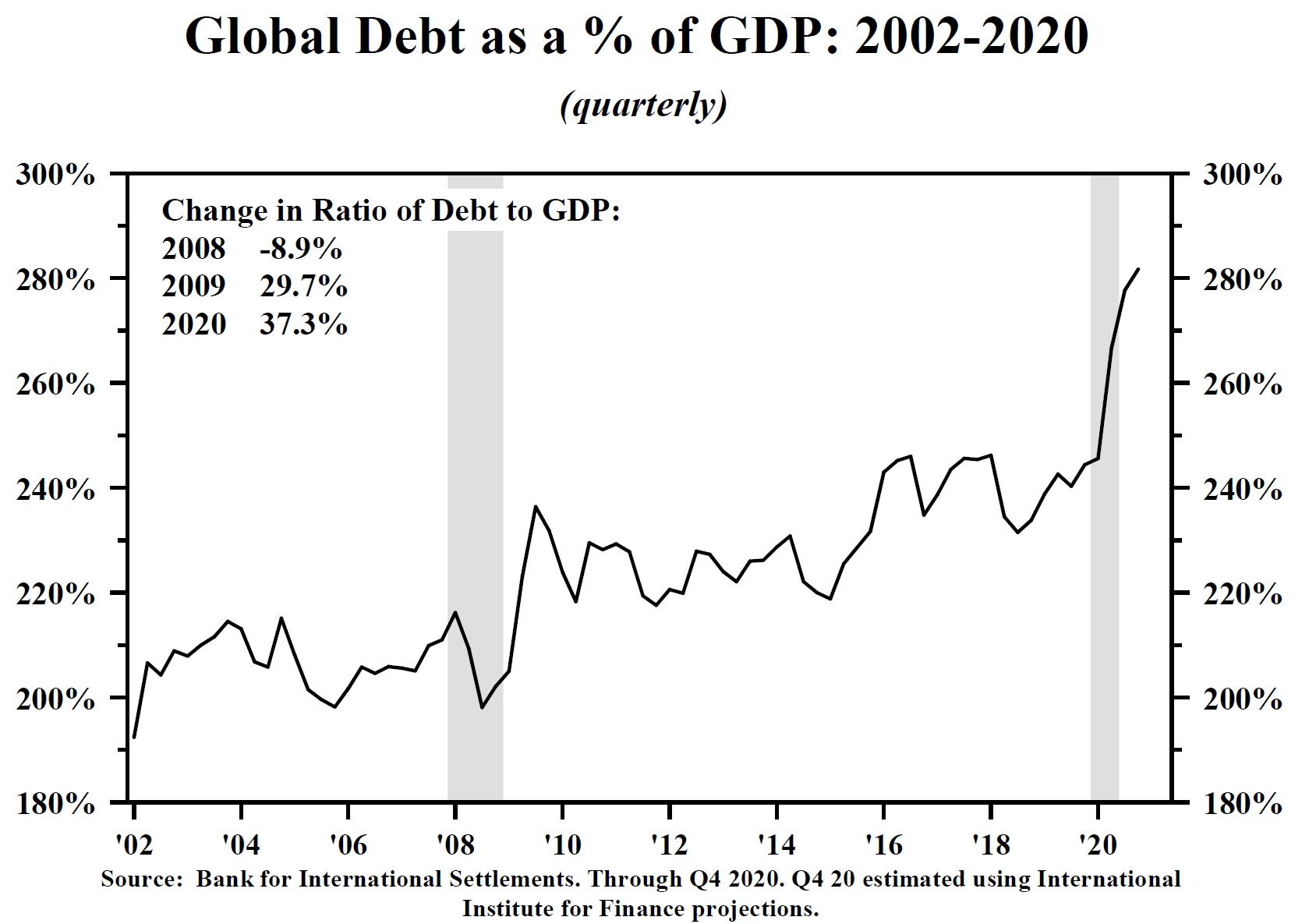

A philosophical difference of opinion as to whether or not excessive government debt is fundamentally inflationary or fundamentally deflationary.

There is no debate about the reality of government debt, its trajectory, its ratios, its severity. The question is what that means to the future – not just this summer but for years beyond. Some truly outstanding minds at this conference believe it will prove inflationary; others believe it will prove deflationary.

Introducing the Master

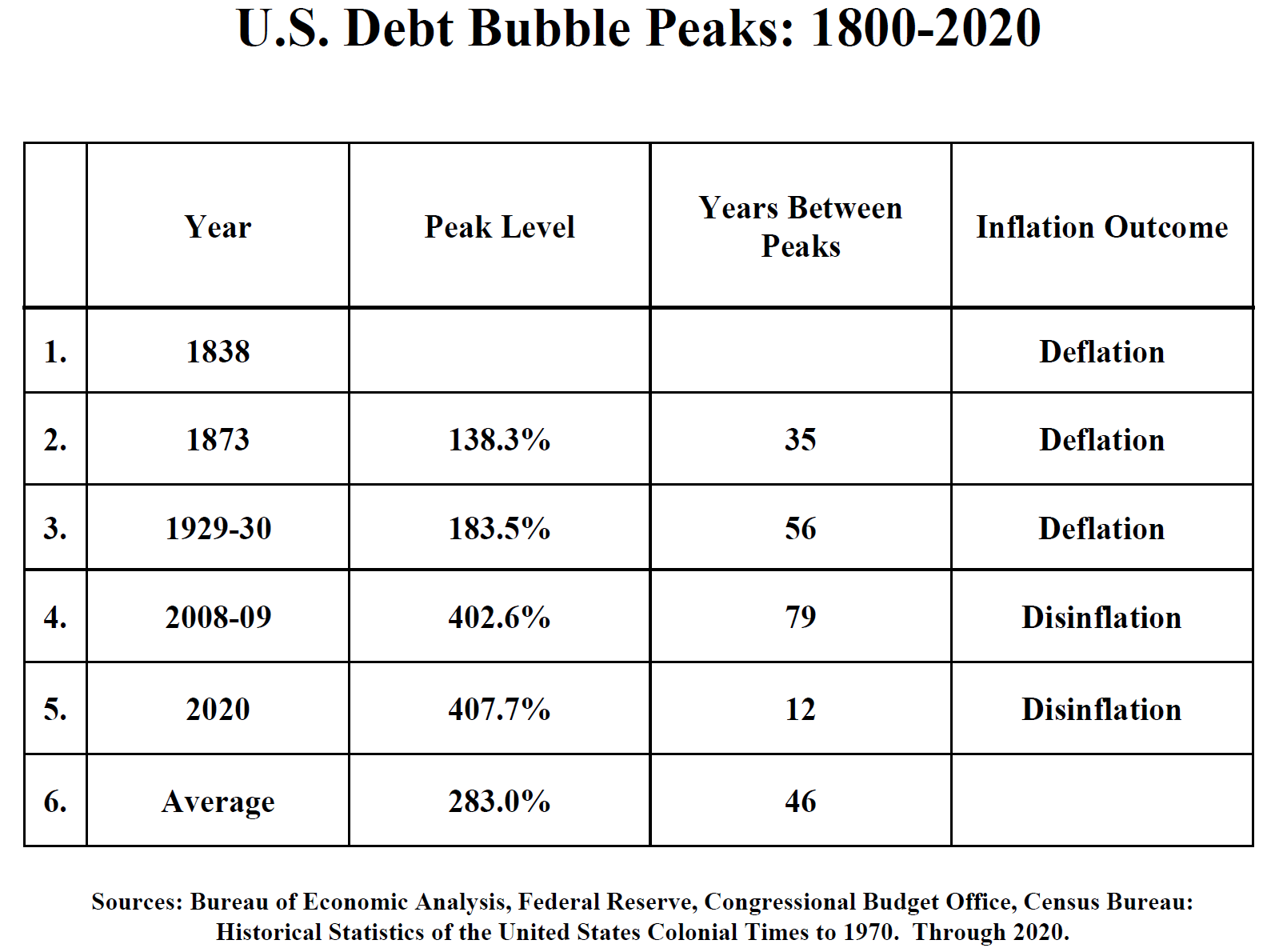

One of those speakers is Dr. Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investment Management Company, one of the most profound influences on my monetary economic understanding of the last decade. He also pulls no punches on the level of government debt we are taking on:

And yet, the testimony of history is clear to Lacy. Even apart from the modern evidence in Japan and other deflated over-indebted developed economies, our own history with excessive debt plays out the same sad outcomes: Deflation.

I have provided other charts to this effect already, but the basic thesis here is that inflation comes from a high velocity of money combined with increases in the money supply and that velocity of money is suffocated by (a) Growing national debt, and (b) The deterioration of loan demand that comes with it.

This remains my view as well.

Can’t we all get along?

So are these two views totally incompatible? I am not convinced they are. I believe the four or five speakers at the conference who mostly hold to an inflationary view right now could very well be proven right that the primary pressure point for the remainder of 2021 will be rising prices, and that the four or five speakers who mostly hold to a deflationary view could be proven right as well-meaning, that the secular forces of downward pressure on growth will resume on the other side of this, and the build-up of government debt in this period will exacerbate deflationary pressures for years to come.

These two groups of speakers may not see their views as super-compatible with one another, but I believe it comes down to timing expectations. And the beauty of this is, they get reflected in the term structure of the yield curve. The short end of the curve may not reflect short-term inflationary pressures because of Fed policy (ZIRP, for one), but the longer-dated parts of the yield curve will answer these things for us over time.

Moving on … to China

Beyond the extensive back and forth around the inflation/deflation debate, by far the most invigorating part of the conference for me had to do with China.

Louis Gave, who is obviously an economist I rely on heavily for his macro research, laid out an incredibly important historical context for how we understand China in the 2020s. His basic thesis is that the key economic event of the early 2000s proved not to be 9/11, but rather the entry of China into the World Trade Organization. Global productivity picked up wherever businesses could outsource production (and for the U.S., that was a lot of businesses).

This led to China’s industrialization, unleashing 500 million new workers in the world. We then picked up the iPhone, saw technology move 500 years in about one year, and between globalization and digitization, witnessed a hyper-productivity boom that put great downward pressure on inflation but also elevated China’s role on the world stage.

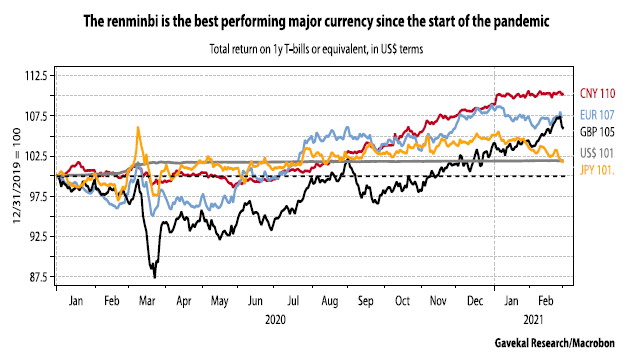

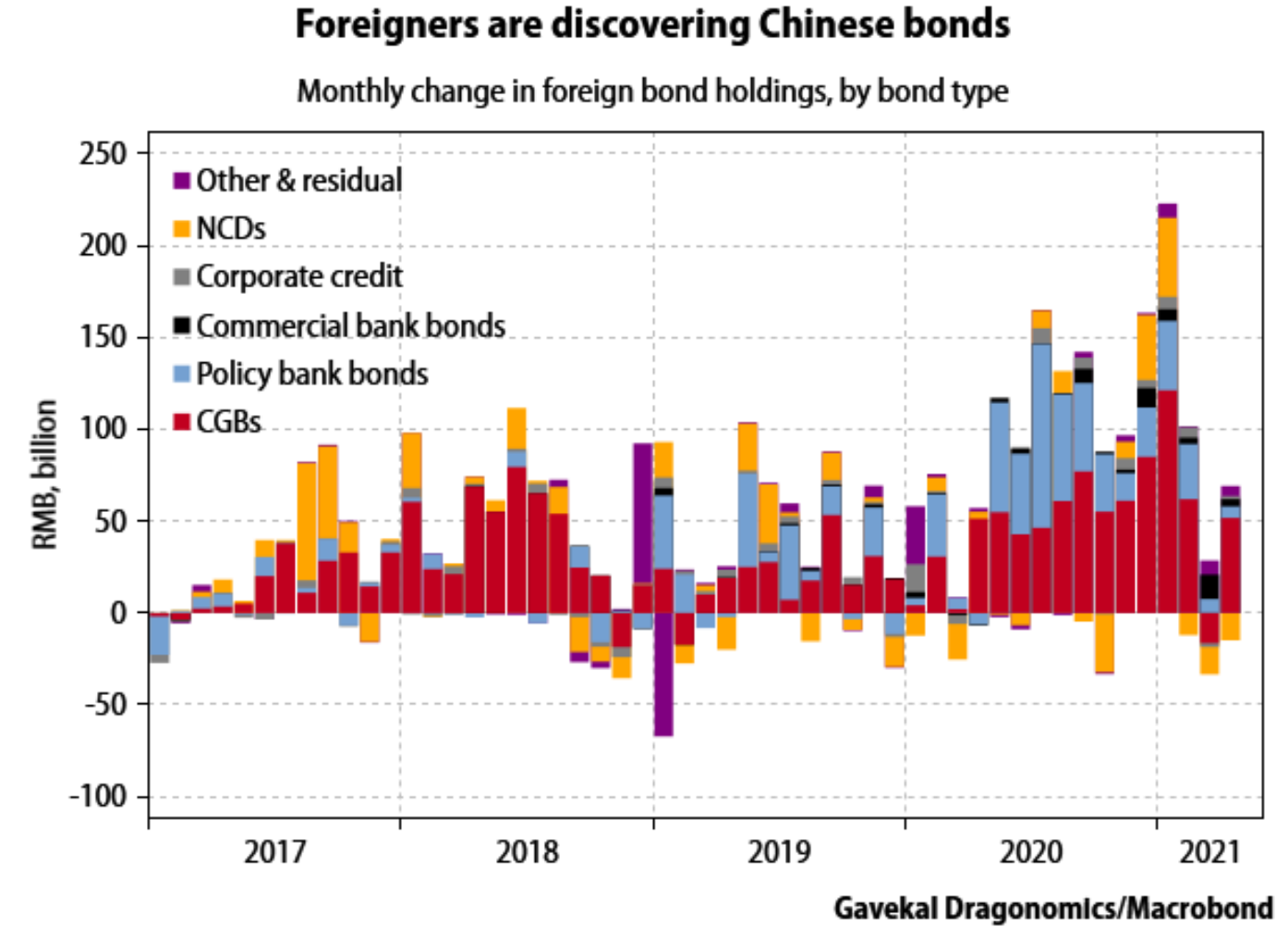

Today, the U.S. is plagued with the decisions it has made after the last crises. Trillions of dollars of debt will handcuff policymakers (few safety net options) and the private sector (lower growth expectations) for the foreseeable future. Investors wanting a “carry” are pouring into Chinese fixed income (over $100-200bn RMB per month, to be precise).

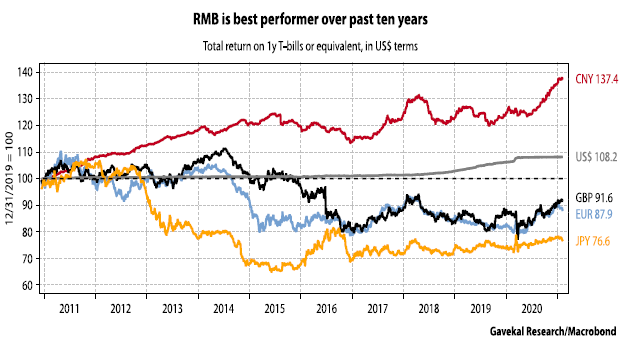

That the renminbi has been the best performing currency since the pandemic started (in the country where the pandemic started) is surprising enough.

But that it has been the best performing the last three, five, and ten years is absolutely shocking (remember when candidate Trump used to bemoan China weakening their currency to compete?).

But that it has been the best performing the last three, five, and ten years is absolutely shocking (remember when candidate Trump used to bemoan China weakening their currency to compete?).

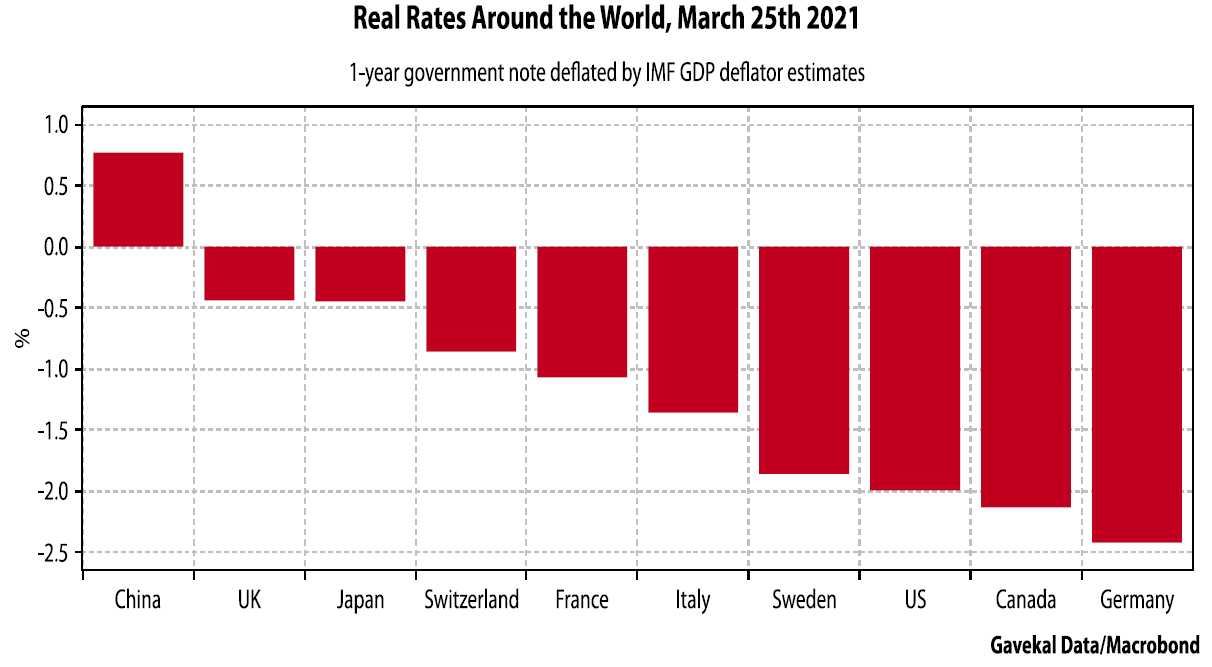

The explanation is so simple, it hurts. Plenty of countries offer a NEGATIVE rate of return, NOMINALLY, on their sovereign debt. But EVERY country, besides China, offers a NEGATIVE REAL RATE (that is, net of inflation).

They run record trade surpluses at the moment (I am less convinced that this matters). And they are finally opening to foreign investment. The U.S. and Europe are all in on excessive monetary accommodation, growing fiscal stimulus, a weaker currency, and trying to create inflation. China and other Asian neighbors are pursuing the opposite policies in each category.

Some conclusions on China

Much of Louie’s thesis promotes the idea of a portion of fixed income allocation to China/Asia (ex-Japan), and I am heavily looking at this. But even apart from this conclusion, it suggests a weaker U.S. dollar, stronger performance in emerging markets equities, stronger performance in energy/commodities, and most importantly, less historical delivery of “risk hedges” where they have normally come. If U.S. Treasuries are where investors “hedged risk” before, are Asian sovereigns where that will happen in this next global economic era?

Not letting the Fed off the hook

John Mauldin, whose weekly Thoughts from the Frontline newsletter I have not missed once since he began writing it, is one of the most astute economic writers of our era. John and I may disagree on some things here and there, but not without five hours of back-and-forth dialogue first. I hosted a panel to finish the conference with John, former Fed governor Richard Fisher, BIS economist Bill White, and strategist Felix Zulauf.

A huge theme of our dialogue played off of what had been a huge theme in about ten-speaker and panel presentations – and that is the risks that are building in the financial system as a result of current Fed actions and policies.

John fears that the Fed may lose control of the narrative. Others (Liz Ann Sonders, for one) say, “Don’t fight the Fed” remains the rule of the day (I am pretty much in her camp – I can disagree with much of what they are doing, and recognize the price to be paid for it, without believing the right thing to do is invest as if they aren’t doing it).

Most of this comes down to a very simple thing: Central Banks today exist as if their role is to stabilize the business cycle. Once you open up that box, it is pretty much impossible to put anything back in it.

Will the Fed one day forgive the United States treasury of its debt? Richard Fisher says, “no way in hell, ever, will that happen.”

Will the Fed take other creative approaches to “backdooring” such a thing, even apart from overt forgiveness? Yours truly says, “I wouldn’t bet against it.”

Both Fisher and I are likely right here. We live in an era where under-estimating the Fed’s creativity is a bad idea, but assuming the craziest of things in your investment actions will create undesirable outcomes.

I will write more in a future Dividend Cafe of what I do and do not believe is in store from the Fed in the years to come. There is no room for arrogance on this, as we are in uncharted waters. But the key takeaway for me was that the Fed right now has more power, more control, more influence, and more burden than ever thought imaginable in economic history, and certainly than 99% of investors understand. Some future crisis is inevitable unless you believe the second coming will arrive first. What you believe the Fed can and cannot do at the time of the next crisis will dictate much of your investment outlook.

So we have more work to do.

Some odds and ends

I’ve run out of time, and I didn’t cover a lot of the peripheral “stuff” I wanted to, which means you’ll get more odds and ends on housing, on crypto, on equity valuations, and more in the weeks to come. You can’t cover a five-day conference in ~3,000 words. But the applications of all that was presented will be thoughtfully considered for some time to come.

Chart of the Week

Early innings?

Quote of the Week

“Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.”

~ Harry Truman

* * *

One of the presentations I did not cover at all was my own, where Ed Yardeni provided some macro commentary, and John Mauldin asked me to comment on how the present state of economic conditions should be applied to a real-world portfolio for a real-world client. I had the distinct advantage of not having to present hypothetically since all of this intellectual mumbo-jumbo is, for us, actually a real-life, real-person, real-goal, real-action scenario, every single day.

My view continues to be that passive investors are playing with fire, and disengaged financial advisors make up the lion’s share of our profession. Our Operation Magnify was intended to proactively, directly, and thoughtfully engage the challenges of the moment. Dividend growth, alternatives, a more nuanced way of using fixed income – these are all solutions and strategies, not products. And they are solutions to real-life problems, the kinds of problems we exist to solve. To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet