From the beginning, the intention of Thoughts On Money has been to take complex topics and simplify them to a short and palatable read. The goal is to help us all become better investors by incrementally improving our own knowledge base. Sometimes this means teaching you the vocabulary of investing and sometimes it means helping you connect the dots around how it all fits together. In today’s discussion, our very own Kenny Molina pushes those boundaries and tackles one of those more esoteric financial textbook topics. Kenny gives you a snapshot of how an analyst thinks and gives us some insight into the relationship between risk and reward.

Without further ado, here is O Captain! My CAPM!

– Trevor Cummings

*****************************************************************************************************************

I recently had a conversation about why a multi-asset portfolio is necessary if you could buy a stock index. Why dilute returns with assets that may, at times, relatively under-perform when you can just buy ‘the market’? (an argument that has been lent credibility with roughly a decade worth of market highs). My answer, of course, was ‘well, what are your return expectations and what are you willing to undertake in order to achieve them?’. I must admit that this is a somewhat vague answer that doesn’t help the individual, who may be unlikely to have the necessary relevant information on hand to create a proper response, to formulate a coherent argument to why they simply hold an index (commonly accessed through low-cost ETFs). However, the conversation got me thinking about the very basic fundamental relationships regarding risk and return, and I thought it would be a fun exercise to breakdown a very basic function that will help investors better understand how portfolio construction is undertaken.

A popular and simplistic, if not slightly idealistic, relationship between risk and return can be found through the ‘Capital asset pricing model’ (CAPM).

Author’s Note: CAPM makes multiple assumptions regarding an investors risk-utility profile, market efficiency, historical returns, among others. CAPM is not used to form investment decisions at The Bahnsen Group. It is used in this article primarily as a framework to help us think about a security’s return relative to the market.

In a nutshell, CAPM attempts to breakdown the relationship between broad market risk, and an asset’s return (commonly equities). For the purposes of our exercise, we will suspend other variables (ceteris paribus for you scholars) and take assumptions as given in order to view a theoretical approach about how an investment professional looks at an asset or combination thereof.

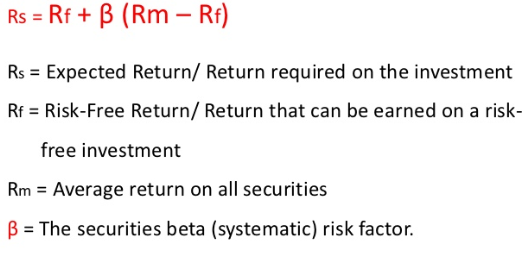

CAPM’s formula and components are as follows:

Source: Investopedia

Firstly, CAPM assumes that, at a minimum, for an investment to be worth considering the investor must make the risk-free rate (Rf), think a treasury bill or the yield from a money market account (let’s use 2% as our risk-free rate). Finally, CAPM attributes the remainder of an asset’s return to a combination of its volatility/risk (ß) in relation to the ‘market risk premium’ (Rm – Rf), what the ‘market’ is expected to return above the risk-free rate (we’ll use 7%).

Putting it all together: Rs = 2% + ß (7% – 2%)

Right away it’s apparent that what can be controlled (input) is the assets relative risk. This is where the question of ‘well, what are your return expectations and what are you willing to undertake in order to achieve them?’ can be quantified. The market, or an index through an ETF, should have a beta of 1, thus no scaling effect of risk. An investor is simply taking on any and all risk implied with broader markets and accepting the returns that may come with that risk. There’s the rub …

Not all investors have the same return requirements, and thus should not take on the same level of risk.

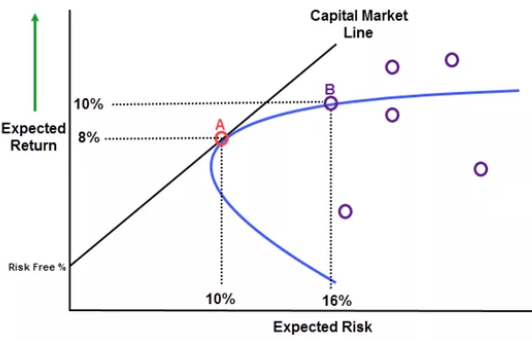

The assumption that a low-cost vehicle and annualized returns of (x%) is all an investor needs to be concerned about when investing is a gross over-simplification. Now I know that we are all extremely rational actors, at least according to more borrowed fundamental economic tenants, so we’re all capable of understanding that just as we would not advise a small child to skydive or a motorist to drive at 15mph on the interstate we should not advise a ‘cure-all’ regarding investments. The implied risk (volatility) of markets may be too great for an investor that needs to cover monthly bills, operate a foundation, etc. It may also be too small for an investor which may need to fund a large expected future liability (e.g. a 25-year-old saving for retirement with a long time horizon and contribution period). It can be helpful to think of an investors return objectives as a field (such as the plane below-modeled according to CAPM) rather than a destination.

Source: Investopedia

There are infinite possible portfolio combinations so attempting to create an ‘optimized’ portfolio through brute force would be prohibitively expensive and thus, impossible. Investors can instead focus on controlling the relationship between risk and return. Theoretically, whichever portfolio can fall on the Capital Market Line is optimally positioned to attempt to achieve the expected return for the given amount of risk. It is, unfortunately, not a possibility for anyone to be on ‘the line’ as the aforementioned ‘suspended’ variables are in fact ever-changing, but let’s brings it back to indexing. Where is the investor if they’re not controlling risk: above, below, diagonal, opposite, in the upside-down? (please don’t sue me Netflix/Stranger Things)

An advisor takes into consideration your idiosyncratic situation, expectations, time horizons, and objectives when attempting to guide you through the changing waters which comprise systematic market risk. With the ultimate outcome of attempting to help you achieve your investment objectives with the appropriate amount of exposure to risk assets. When there are unforeseen moments in the investor’s life or markets in general, an advisor takes the time to re-evaluate the whole of the portfolio and any updated situation and objectives. The ‘market’ meanwhile cannot be adjusted or scaled, simply taken ‘as-is’. So the next time you come upon the same conversation I did, hopefully, you understand that just as nothing in life is simple neither are markets.