Things rise and fall, start and stop, expand and contract – it’s a fact of life. School children take a recess, middle-aged men get receding hairlines, and business cycles have recessions.

Are we going to have a recession? Yes. Should I be concerned? No….not if you’re a prudent investor.

Being a smart investor requires a complete understanding of how business cycles work so that you don’t fall victim to the “sky is falling” fears that come with inevitable economic recessions.

This week’s TOM provides you insights into how to view the next economic downturn and how to survive it.

And off we go…

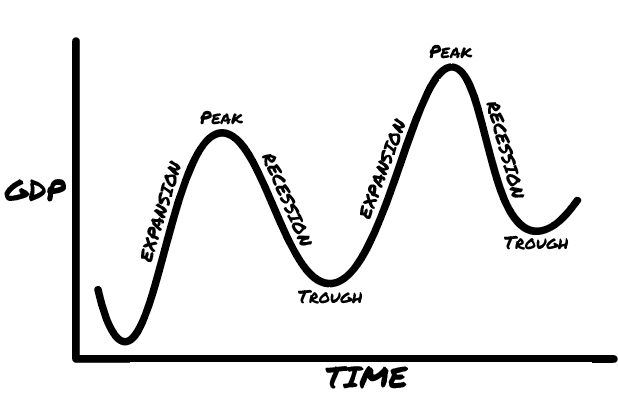

This is what a business cycle looks like:

In the last 166 years, we’ve had 33 expansion/recession cycles and are currently in a prolonged expansion since June 2009 – that’s 117 months and counting. The longest expansion recorded by NBER is 120 months (March 1991 – March 2001).

These cycles are as natural as breathing. As I inhale, my lungs expand and as I exhale my lungs contract. Same concept.

Regardless of its inevitability though, people are still anxious to know when the next recession will hit. Yet this is unknowable. Here’s what we do know:

- They can’t be predicted

- They’re born out of excess

- The next one won’t be the same as the last

- The economy isn’t the stock market

They Can’t Be Predicted

“The function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable.”

– John Kenneth Galbraith“The rule of thumb is that unless you predicted the expansion would last this long you don’t get to predict when or how it will end. Which means basically no one gets to predict when or how it will end.”

– Morgan Housel

According to the American Gaming Association, 40 million Americans filled out 149 million March Madness brackets last week. To create the perfect bracket you’d need to predict the outcome of all 63 games. If you flipped a coin to make each of these predictions you’d have a 1 in 9,223,372,036,854,775,808 chance. That’s 1 in 9.2 quintillion or 263. As of this writing, the NCAA says that one bracket remains perfect through the Sweet 16 and this is the first time this has ever happened. Could this be the year of the perfect bracket?

Some things are not impossible to predict, but they are improbable. This is as true for predicting the perfect bracket, as it is for predicting the next recession. In case you were wondering, 1 in 9.2 quintillion is not good odds.

Although the odds of these predictions are slim, the sharing of opinions are vast. If you are looking for someone to tell you exactly when the next recession will hit, you won’t need to look far. Philip Tetlock, author of Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction describes it this way:

“Open any newspaper, watch any TV news show, and you find experts who forecast what’s coming. Some are cautious. More are bold and confident. A handful claim to be Olympian visionaries able to see decades into the future. With few exceptions, they are not in front of the cameras because they possess any proven skill at forecasting. Accuracy is seldom even mentioned. Old forecasts are like old news—soon forgotten—and pundits are almost never asked to reconcile what they said with what actually happened. The one undeniable talent that talking heads have is their skill at telling a compelling story with conviction, and that is enough. Many have become wealthy peddling forecasting of untested value to corporate executives, government officials, and ordinary people who would never think of swallowing medicine of unknown efficacy and safety but who routinely pay for forecasts that are as dubious as elixirs sold from the back of a wagon. These people—and their customers—deserve a nudge in the ribs.”

Truth: Recessions can’t be predicted with perfect accuracy.

They’re Born Out of Excess

“Bull markets are born on pessimism, grown on skepticism, mature on optimism, and die on euphoria.”

– Sir John Templeton

In Aesop’s Fable, The Dog and his Reflection, we read about a content pup who’s jaunting along with a fresh piece of meat he got from the butcher. When he comes to cross a bridge, he sees his reflection in the water. Mistaking his reflection for another dog with a larger piece of meat, the hound unclenches his portion to bark and overtake the portion of his foe. As he opens his mouth his piece of meat falls into the water and is lost.

An unhealthy desire for more than we have is the impetus of many recessions.

– In the late ’90s, during the dot com bubble, people stopped caring about valuations because they believed stock prices could only go up. Talking about your stock gains at every social endeavor was the thing to do and nobody wanted to miss out. This excess could only last so long.

– In 2007, pre-financial crisis, people stopped caring about valuations because they believed housing prices could only go up. Talking about your real estate gains at every social endeavor was the thing to do and nobody wanted to miss out. This excess could only last so long.

Each of these examples was not only a case of consumer excess but a culture of excess. In 1999 investment banks continued to underwrite IPO’s for technology companies with no earnings and in 2007 mortgage lenders continued to issue mortgages to consumers without sufficient income.

Eventually, the excess leads to too many folks barking at their own reflections and their treasure ends up under water.

The Next One Won’t Be the Same as the Last

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes,”

– Mark Twain

Perhaps better stated as, “The Next One Won’t Be Exactly the Same as the Last.” Each recession is unique, and it will have its own contributing factors. We will innately want to believe the next recession will look just like the last. Human beings are full of these cognitive biases that lead us to make conclusions based on a limited amount of data. Very much colored by our own experiences. We anchor to memories that are front of mind and especially those that were painful.

I remember when our cat Scout was just a kitten and he jumped on to our kitchen table curious to know what I was eating. I happen to have soup and it had not yet cooled down enough to begin eating. That confident little kitten marched right up and took a taste of my soup. He immediately retreated, shaking his head, pawing at his mouth, and taken back after burning his tongue. Scout never attempted to taste my food ever again.

Some investors will never buy a tech stock after what they experienced during the dot com crash. Other investors may never buy a bank stock following the financial crisis. It’s not the industry or sector that dealt this blow, but rather the perversion of excess that surrounded it at the time.

Each recession will have its own story to tell.

The Economy Isn’t the Stock Market

For this final pearl of wisdom, I would encourage you to read David Bahnsen’s piece on Market Epicurean from December of last year: Will Business Confidence Undermine the Trump Economy

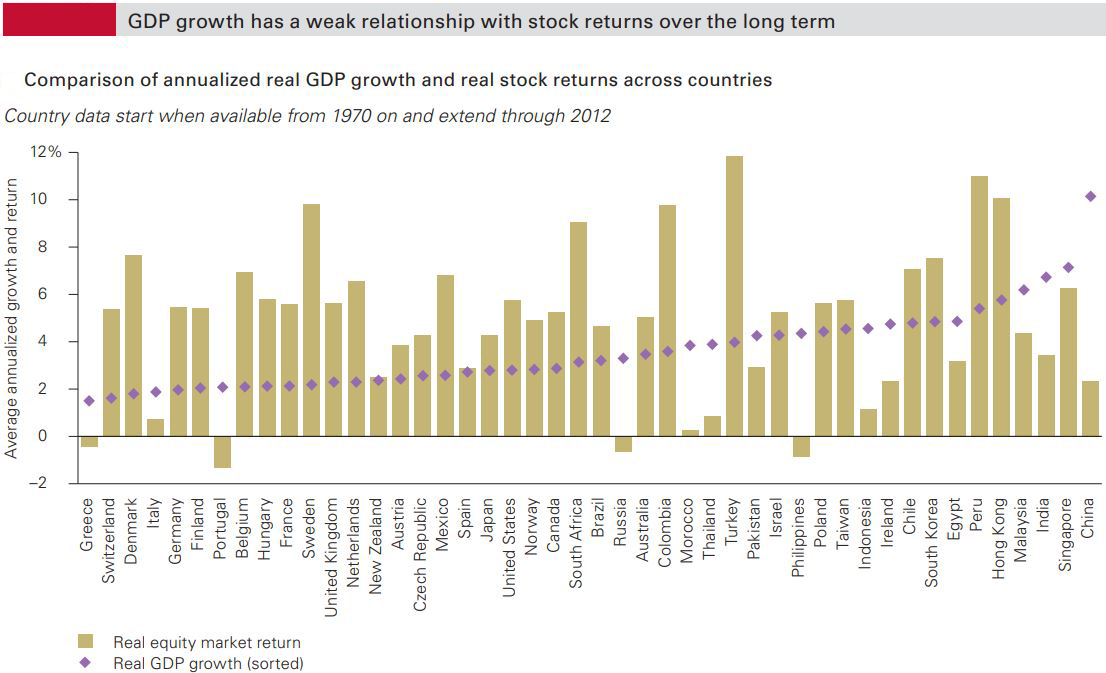

This graph below should also prove to be useful:

Source: Vanguard

The key takeaway is that GDP growth and equity returns do not have a strong correlation. The market and the economy are not one in the same. If you were to look at historical stock market returns leading up to and during a recession you will find some of those returns are positive. Ben Carlson, author of the blog A Wealth of Common Sense found that “stocks have actually risen during 4 out of the last 9 recessions. And stocks were positive 6 out of the past 9 times in the year leading up to the start of a recession.”

Essentially, these facts should bring you peace of mind. They allow you to divorce your fears about a recession from your assumptions about what it might do to your portfolio.

The Sky Isn’t Falling

Today we are one day closer to a recession than we were yesterday.

When that next recession arrives, I hope you are not surprised or fearful. I hope you remember the truths that we discussed today and that you’ll feel equipped to stay the course.

Just remember, business cycles are as natural as breathing.

With that said, I wish everyone a great rest of the week and this is TOM signing off…