All Hands-on Deck

In 1997, Hands on a Hardbody was awarded the best documentary by the audience at the Los Angeles Film Festival. A documentary following the annual Hands on a Hardbody competition in Longview, Texas. A city name [Longview] fitting for a competition that entails 24 contestants challenged to keep their hand on a pickup truck for as long as they can. No leaning, no squatting, and the last contestant standing with a hand on wins the pickup truck.

In 1995, the competition covered in the documentary lasted 77 hours.

SEVENTY-SEVEN HOURS! Over three days! I have trouble missing a few hours of sleep in a night. I could not imagine how these contestants must’ve felt after three long, sleep-deprived days.

In this competition, the winner need not be the fastest, the strongest, the tallest, or the most athletic. The spoils go to the contestant that can endure the longest; time is the key to success.

Investing is similar. Wealth isn’t always determined by income, family, fame, or IQ. The spoils go to the investor that can endure the longest; time is the key to success.

Back to School

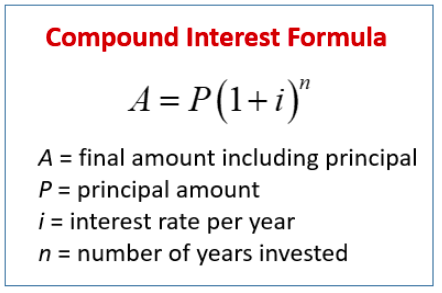

Let me take you back to your first college finance course – day one, chapter one. The compounding interest equation:

Source: OnlineMathLearning.com

Three variables will determine the final amount in this equation: principal amount (what you start with), interest rate (your return), and the number of years you stay invested. I’d like to break our discussion into three sections and discuss each of these unique variables and their impact on your financial plan and your portfolio.

Why this equation specifically? Well, compounding interest is the magic formula that builds wealth. Albert Einstein is often credited with saying that “the most powerful force in the universe is compound interest.”

So, let’s take a deeper dive into the components of this powerful force that is compound interest.

A Matter of Principal

As the old adage goes, “you get out of it what you put into it.” The first step to letting compound interest do its magic is – putting something into it. In the beginning, your contributions matter most.

Later on, I will note that “time” is the most important variable in this equation, but for time to do its magic, it first needs a good base, a strong foundation. Your contributions, the money you save today is what creates this base that will grow over time.

Imagine the proverbial snowball rolling down the hill – it grows and grows and grows, but all of this starts with snow sticking onto that original base, then new snow sticking onto that next layer, and so on. In the beginning, your returns will just be calculated based on what you contributed; down the road, you will see the power of your interest-earning interest. Or, as Benjamin Franklin so eloquently put it, “Money makes money. And the money that money makes, makes money.”

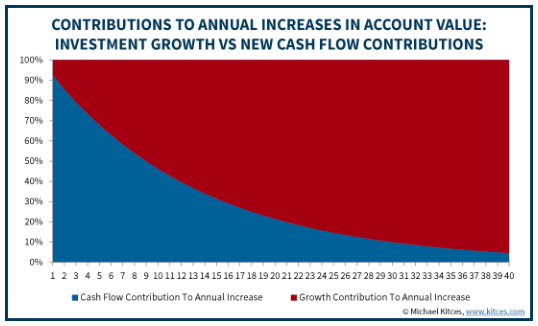

Financial blogger, Michael Kitces, provides a very helpful visual of what this looks like over time:

This graph depicts a saver contributing $3,600 annually with an 8% return. Most of the account growth is attributable to the contributions or savings (blue) each year in the beginning years. Over time, this shifts, and the primary driver of growth becomes the growth of the portfolio (red).

The moral of the story, the more you set aside (save) today, the greater future wealth it will create for you in the long run. 97% of Buffett’s wealth was accumulated after 65 because of this very principle depicted above.

Of Great Interest

We talked about your contributions, what you save. We will talk about time, how long you stay invested. And both of these variables are what I would categorize as “controllable.” You have a great influence (control) over these two inputs. Your rate of return is a bit more out of your control; no matter how hard you “try,” you can’t always manipulate the results to your exact liking. Some decades will provide generous results, and some decades will be stingy. The results are lumpy and unpredictable. Yet, our “returns,” the uncontrollable factor, tend to garner most of our attention. Returns are a fun thing to chase and a fun thing to brag about.

Although returns are unpredictable and, in some seasons, disappointing, some best practices can help position you to receive healthy returns over time. Note, the difference between a 2% return and an 8% return over time is meaningful. A million dollars compounding at 2% over 30 years won’t even double in value, while an 8% return multiplies your original investment by 10 – that’s the difference of $1.8mm vs. $10mm.

Here’s the key, when picking out investments and designing your investment portfolio, you should always ask this very simple question: what is the expected return on this investment? Accurately determining the expected return in the short term will often be impossible, but forecasting the return of broad asset classes, like bonds or stocks or real estate becomes much more predictable over longer periods of time. There are simple valuation formulas and historical data to give you the needed context for making these forecasts. I am not saying that these assumptions would be accurate down to the decimal, but rather that the range of variation – the dispersion of possible outcomes – shrinks when measuring longer holding periods.

Now, this may seem silly and simplistic to just ask, “what’s the expected return?” but I will tell you that most investors don’t. Imagine an investor owning a portfolio made up of 50% bonds yielding 2% and 50% stocks. Let’s say this investor has an expectation of getting a 10% return. Well… if half the portfolio gets 2%, then the other half will need to produce 16% (all after taxes and fees) to accomplish this net return target. Is that realistic? Is there historical precedence for this assumption? Most don’t get this far in the thought exercise; they just stop after declaring their expectations.

Time is on Your Side

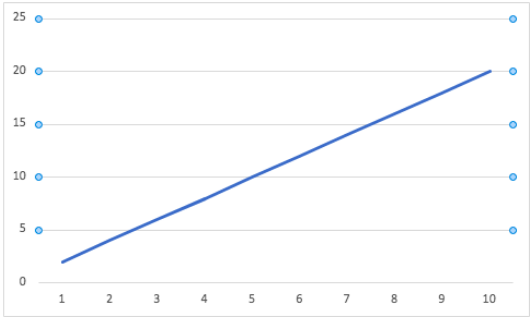

Looking at this compounding interest equation, at first glance, what do you notice about the “n” (number of years) variable? It sits on a pedestal, above the other variables, a font modification we call superscript, and it is “super” indeed. In math, this elevated variable is referred to as an exponent. When you graph out two variables being multiplied by each other, you get a linear graph, something like this:

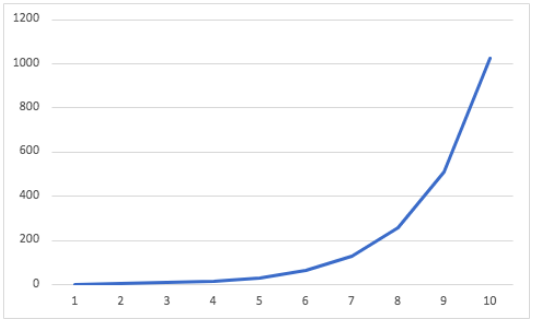

When you see two variables, one being an exponent, the graph takes on a new shape:

This mathematical shape is where we derive the adjective parabolic, often used to describe something with a compounding momentum, seen in this curve with an ever-steepening slope. Viruses go parabolic, gossip goes parabolic, and over time portfolios can benefit from parabolic growth.

All of this hinges on one simple variable: time.

Time, a fleeting resource, scarce in our culture, treasured yet not respected. We’ve become wired for instant gratification, which is the antithesis to successful investing. So, what’s the answer to the test? What’s the key to building significant wealth? Staying invested for a long time.

Charlie Munger, the business partner to Warren Buffett, puts it this way, “The first rule of compounding is to never interrupt it unnecessarily.” Here’s the hard part, our investments don’t always behave the way we want them to, and our emotions can lead us to be shortsighted with our decision-making. Investments tend to take one step backward and two steps forwards – it’s in their very nature – but we often fiddle in the midst of this dance and settle for one step backward and one step forward, or worse.

Look back at that second graph I posted above, the depiction of an exponent. Regarding investments, what part of the growth curve looks more attractive, the beginning or the end? The end, where the curve is steep, of course. What’s the difference between the two? More time. That is what exponential growth looks like, and its treasures are reserved for the patient and enduring.

I cannot overstate the power and impact that time has in this equation. If you desire to build significant generational wealth, you need to have a generational perspective and a generational time horizon. What happens this week, this month, or even this year, will be a blip on the radar over a lifetime of investing. Yet, let me ask you this, what captures more of your attention and instills more anxiety, the daily news cycle or your long-term financial plan?

One of my favorite finance writers, Morgan Housel, summarizes it this way:

The time component of compounding is why 99% of Warren Buffett’s net worth came after his 50th birthday, and 97% came after he turned 65.

Yes, he’s a good investor.

But a lot of people are good investors.

Buffett’s secret is that he’s been a good investor for 80 years. His secret is time.

All Contestants Welcome

My intuition tells me that it would be hard to predict the winner of the Hands on a Hardbody competition each year. I feel like my eyes would deceive me. I would be quick to assume some attributes or qualities would correlate with success.

Investing isn’t much different. I could tell you about countless professional athletes – extremely high-income earners – that went broke. I could also tell you about janitors, librarians, and secretaries – real people – that left millions of dollars, significant wealth, to charity in their will. Why? Because the attributes of investing success aren’t always obvious, but they are simple – save, grow, wait.

That’s it. That’s the secret sauce. Save, grow, wait.