Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Market volatility is on a roll, with the VIX now double the level it started the year at. This week saw the biggest up day we have had all year, followed the very next day by the biggest down day of the year.

A lot is happening, and we can and will unpack it in today’s Dividend Cafe, but we will not leave it there. The takeaway today will be what to do about it (or not do about it), and that is why you should enter the Dividend Cafe. Knowledge followed by action. To that end, we work.

|

Subscribe on |

The root cause

There are two contexts I believe worth covering about recent market volatility. One is a general and high-level reality that speaks to the nature of markets and sentiment. The other is a more specific and technical consideration of what is actually going on and what some believe could happen later.

In the most generic of senses, market volatility is enhanced by the uncertainty of what the Fed will do and by the removal of Fed support. That last section has to be qualified.

Tighter is not the same as Tight

A Fed Funds rate of 0.75% and a $9 trillion balance sheet is still hyper-accommodative monetary policy. The Fed is removing support, but it has not removed support. Where it is, where it will be for some time, and where I reckon it goes, all still land on the side of “easy” or “loose” or “accommodative” monetary policy, relatively speaking.

But that is not all that matters here. The direction of monetary policy matters to market sentiment, and directionally, no one sees the Fed about to cut rates or ramp up liquidity in financial markets; and directionally everyone does see them doing the opposite (higher rates, less liquidity). So yes, while I do not believe we are in a universe that can be considered “tight” and “restrictive” – we are directionally moving tighter, and that exacerbates volatility.

Certainly uncertain

As a general rule of thumb, marginally, market valuations stand to decline when interest rates increase. I have explained how stock prices work before. The key problem here is that one does not know the real magnitude of the impact to valuation – just that there is an impact to valuation. So that uncertainty of where rates go and how much magnitude it creates in equity valuation becomes a source of uncertainty – or as we call it when manifested in stock prices – volatility.

At a high level, markets are dealing day by day and week by week with the broad uncertainty of where rates will go, what impact to valuations will be (or ought to be), and the reality of macro conditions.

I do want to make a very important clarification: The particular uncertainty of particular Fed actions around a particular economic framework of liquidity, interest rates, monetary policy, etc. – is unique right now; most of the other uncertainties people refer to are what we call “being awake.”

Is manufacturing up or down? Did GDP do this or that? Are there enough jobs? Are there enough workers? Sorry, but even geopolitical disruptions -Russia, Saudi, China. All of these things are there every single day, forever and ever. Sure, sometimes the answers are different. One week or one year a box is checked and another week or year a box is unchecked. But economic macro particulars have always been unpredictable, have always been wrongly forecasted, and have always been riddled with a good thing here and a bad thing there.

I would love to tell you that there is a way to predict the next durable goods order and the next BLS jobs data (there isn’t) and that there is a way to take that economic data knowledge and translate it to a portfolio win (there isn’t). But I can’t tell you either thing, and that’s okay. There are ways to make money as an investor without knowing the next PMI print.

The unique uncertainty of the moment is Fed-driven, and this is a direct by-product of how important they have made themselves in the financial markets. We care so much about what they do with liquidity and rates because they have done so much with liquidity and rates. We live and die by the sword, in that sense.

Takeaway #1: Volatility is generally enhanced because uncertainty on Fed actions is generally enhanced.

You’re cut off

The other element I brought up is fear of removal. Has the Fed provided a backstop to markets that is now going away? The best way to answer this is with three answers because why make things simple?

(1) Yes, the Fed has provided a backstop in financial markets, for a long time

(2) No, that backstop is not going away

(3) Yes, marginally, there is less backstop coming than there has been

Market investors concerned with REAL problems in the global economy, where a lender of last resort is REALLY needed, where a “left tail risk event” REALLY happens, should want the Fed to have backstop tools in their toolbox. But the idea of a “permanent” assist to markets with permanent intervention is absurd. It leads to a bad drunken episode and then a bad hangover.

Right now, part of market volatility is markets reacting to the proverbial punch bowl being taken away (that analogy is old and tired, but nevertheless common and well understood). I didn’t make up this analogy, but if we are going to use it, I am going to really use it.

Punch Bowl Explained

This analogy is used to imply that the concern is the punch bowl being taken away – that is, the “party stops” and the hangover ensues (so in financial markets, the good times of easy money get taken away, and then the hangover of tighter money begins – less liquidity, higher credit spreads, compressed activity, less exuberance, etc.).

My problem with the analogy is this: It implies that the “party” (punch bowl) phase was great, and the “hangover” (sobering up) phase is terrible. But I ask you: Do you think it is fun to be around someone who has imbibed too much?

I have never found someone getting too loud, too obnoxious, too physical, too whatever, all that fun. In fact, I always found them getting sent home to sleep it off a good thing.

I get exactly what the analogy is trying to convey. I just want to offer my two cents: People paying absurd prices for assets is NOT my idea of a good time. And prices coming back to a framework of reality, IS a good thing, in the end. I know pain happens in between. But punch bowl analogies always miss the mark in this one thing: Someone sobering up is actually good.

Takeaway #2: The Fed is, to some degree, curtailing a period of excess, and yet that is a good thing in the end, period.

Okay, back to the market

So volatility from macro “stuff” is normal.

Volatility from Fed uncertainty is enhanced right now, and the inevitable consequence of the Fed playing too big of a role in financial markets.

And some short-term pain to sober up the markets is perhaps what is needed.

That’s the high-level state of affairs. But what is in the weeds here? What are the real granular economic concerns that people don’t talk about at parties right now, either because the subject is too complex, or because they spent too much time at that aforementioned punch bowl?

Room to invert

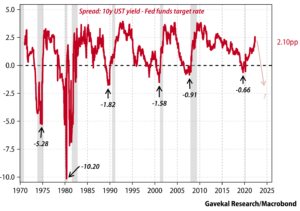

The 10-year bond yield right now is somewhere around 2.25% higher than the Fed Funds rate (3.0% vs. 0.75%). The Fed could raise the Fed funds rate 225 basis points and still not invert (and that assumes the 10-year doesn’t move). Markets wonder if the Fed has to invert this and do so significantly. When that happens, it is usually recessionary. Note below – COVID, the GFC, dotcom, savings & loan, and the big daddy of when Volcker went after inflation.

In that 1980 case, we saw a ONE THOUSAND POINT inversion of fed funds to the ten-year. Right now, we are 225 points UNINVERTED. I mean, be concerned about this all you wish, but these analogies to Volcker are just so idiotic I lack the words.

Can it change? Well of course it could. Powell even mentioned Volcker’s name this week and, wait for it, said a nice thing about him! Are we entering a new regime of Fed discipline that looks to a hyper-tightening of financial markets that uses a deep recession to purge our excesses?

Nope

I do not believe we have a Fed governor on the planet who has Volcker DNA. I do not believe the government’s debt profile, the significant focus on corporate leverage as a source of economic growth, the political revulsions against recession, and all the other different realities of today vs. then allow for this as a serious consideration.

Can rates go higher than people think? Sure. I already have had to adjust my expectation of where they will go higher from where I was a few months ago. I continue to believe (with great precedent) that rates fall short of what consensus expects them to be, and I would be a buyer of the 2-year Treasury here, but I certainly accept the possibility of a Fed that surprises on the tighter side relative to my own expectations.

But what I believe is that when the Fed brings the return on invested capital below the cost of capital, they will blink. Rising labor costs, declining inflation expectations, or any number of things could bring that outcome to bear, and that process as well as fear of that process is where we are now.

Takeaway #3: The worry is that the Fed goes full Volcker, and I don’t think that’s a very smart worry

What to do

The environment now favors value over growth, a focus on valuation over anticipated rising multiples, and high credit quality. These things are abundantly clear. But long-time readers and certainly clients of TBG know that this is not merely tactical for us; these are pretty evergreen practices in our portfolio management (creating relative outperformance and underperformance, gladly, at varying times in the cycle).

How much dividend growth and value and so forth continue to outperform does, to some degree, depend on what the Fed does, how market sentiment plays out, and how much excess has to get purged from the period of excess we have been living in. Dividend growth investors face less of a hangover because they didn’t drink that much at the punch bowl. Shiny object investors may need more time to detox. You get the idea.

Behavior

Am I daring to suggest people with a GOOD portfolio need to ride out bad times, even prolonged ones? Of course, I am because the moral authority on which we dispense advice (and expect clients to follow it) is rooted in trustworthiness. And anyone who tells you otherwise does not deserve trust.

You don’t sell long-term assets because of short-term dips.

You don’t invite ways to be wrong about an exit and a re-entry – you minimize chances to be wrong.

You don’t invite a cycle of regret about when you sold and when you didn’t buy back in and all that kind of stuff.

Takeaway #4: Have the right portfolio, the right plan, and avoid the wrong behavior.

Chart of the Week

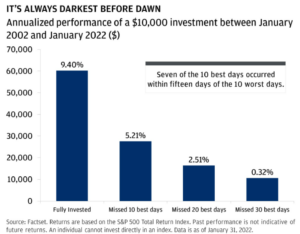

Market timing doesn’t always work out well, and the costs are high.

Quote of the Week

“People who are unable to motivate themselves must be content with mediocrity, no matter how impressive their other talents.”

~ Andrew Carnegie

* * *

It’s not going to be an easy period for a while. I doubt we go in a straight line down, but I also doubt we have seen a market bottom. I believe a market transition is happening that will be volatile itself, and we will come out of it grateful that we did not violate our principles.

Two people will come out unhappy. Those who lack principles of investing. And those who do not follow the principles they have.

We won’t be guilty of either. We won’t let you be guilty of either. To those ends, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet