Dear Valued Clients and Friends –

Who would have guessed that at the one-year mark of the worst market drop since the Great Financial Crisis, one of the hottest topics in financial markets is whether or not we are in a “bubble.” Am I the only one that sees a tiny bit of irony here? A year ago, the conversation was entirely focused on whether or not millions of American people were going to die, how long the entire American economy would be shut down for (hint: it lasted longer than 15 days to bend the curve), and whether 18,000 in the Dow would prove to be low enough.

Painful times, painful memories.

Fast forward to Q1 of 2021, and tell me if any of these buzz words sound familiar?

Bubble. Mania. Valuations. SPAC craze. Robinhood. Euphoria. New highs. Inflation. Hyper-inflation. Excess. Runaway growth. Overheated. Frothy. Bullish sentiment.

So I ask you – would any of those words, phrases, concepts, or emotions have made any sense in the context of the unprecedented contraction/recession/lockdown/market crash just one year ago? It is not just that these words and fears and thoughts and ideas would not fit with the narrative of a year ago; they would have been the polar opposite of what was happening a year ago, right?

Today I want to look into the very idea of bubbles, evaluate as intelligently and objectively as I am able what is going on in markets right now and what is not going on, and see if we can’t offer a little clarity into a subject that I think gets quite polluted by poor punditry. Of course, if it weren’t for poor punditry, wealth advisors like us would have a lot less cleaning up to do.

Join us in the Dividend Cafe …

Weather forecasts that vary, dramatically

There is a tinge of irony in the fact that so much of the fear of yesterday has been replaced by a fear that falls into the exact opposite category today. Predicting a snowstorm one day and a heatwave the next is not inherently impossible, but it does take a pretty wild flexibility in how one views the world. Now, in fairness, Keynes was right to say that “when the facts change, I change,” and perhaps that’s all this is. Perhaps the folks a year ago who practically guaranteed us that the 36% drop in 31 days, the 18,500 level Dow, the sheer pandemonium in markets, would all prove to be a mere opening act to the horror that awaited – that lower and lower lows awaited those who stayed long equities – perhaps these folks (in many cases, the exact same people) who now forecast “runaway inflation” and “the mother of all bubbles” simply changed their tune in response to changing circumstances. They had every right to be wrong a year ago, and they have every right to have a new opinion a year later – whether that opinion set proves to be right or wrong itself.

By the way, who cares?

It really is not the job of the Dividend Cafe or the fiduciary advice granting task of the Bahnsen Group to keep a report card on various weather forecasters out there. Regardless of the motives of various pundits, and regardless of their batting average, our job is to call balls and strikes ourselves and to align our client portfolios with our view of the world. Someone who called X a year ago wrongly is not necessarily wrong about Y a year later. So we have to look at Y on its own merits, separate from all other factors and past happenstance.

The only reason I bring up X vs. Y in the way I do here is to generate appreciation for the tidal shift in what we are talking about. In less than a year, we went from the predominant conversation being “how low can we go?” to a predominant conversation of “how high can this go?” It’s odd. It’s fascinating. It’s abnormal. And yes, I do believe the motives of some are sinister (I only question their motives because I think that is less insulting than questioning their competence).

But really, we have work to do to understand what is going on, and that is the work I want to do.

A rally is not a bubble

It is entirely possible to be surprised by the level of market advance off of the COVID bottom, and the rapidity of the market advance, without believing it to be a bubble (or the adjective form of bubble, “bubblicious.”) I suspect this is the most conventional view, and more or less reflects my own when talking about the broad market … the events of March 2020 were over done … they reflected a “national margin call” of forced selling that was bound to result in capitulation … they were met with shocking levels of monetary accommodation that included lifeline levels of support to corporate credit that resulted in de facto support for equities … the virus became a more infectious disease than initially thought but a much less fatal one … the fears of overrun hospitals did not come to fruition … the ability of large portions of the economy to absorb remote work and life proved more resilient than thought … the relative valuation of risk assets were all boosted substantially by ZIRP and QE (zero interest rate policy and quantitative easing) … international market conditions were no competitive threat to U.S. market options only boosting the relative attractiveness of our markets … fiscal stimulus juiced consumer spending and household disposable liquidity … other peripheral fears like housing pressure proved totally unfounded as superior equity now vs. excess leverage in 2007 made a world of difference … etc, etc.

In other words, there were a lot of good reasons that markets tanked a year ago, and there were a lot of good reasons markets rebounded since. Fair enough.

The question now is what to make of the present state of affairs.

Grab a dictionary

I am not convinced that we have the terms tightly defined enough to really do this topic justice, but I am not sure that there are dictionary definitions for some of these concepts. Justice Potter Stewart once said he could not define pornography, but knew it when he saw it. Perhaps there is some of that dynamic at play with bubbles – they lack a quantifiable definition, but there is a sort of subjective, qualitative reality attached to them that is hard to deny. But I do think some filtering can be done.

A big rally, is not in and of itself a bubble.

An increase in value, is not in and of itself a bubble.

Even “excess valuation,” is not the same thing as a bubble.

Allow me to offer a few “differentiators” on the concept of bubbles.

Debt vs. Equity

Something entirely funded with equity can be really over-priced. One can pay $100 for something that is worth $50, and that “mark to market” loss can be severe. But that poor investment paid in cash by an over-anxious investor is limited to that person’s poor judgment or anyone else who joined in, in this example. But let’s say the masses come in – and all pay $100 for something worth $50 – is that a bubble? The difference is that once you describe the masses coming in, you have almost certainly switched from an equity issue to a debt issue because the “masses” don’t do anything with their own money.

The historical reality, and more importantly, the systemic risk exposure, is always encapsulated by debt financing of whatever the over-priced asset is. Long Term Capital Management hedge fund blows up on overpriced bonds in 1998? They were levered 90-to-1. The dotcom bust of 2000? Unprecedented levels of MARGIN buying. The mother of them all – the nastiest bubble the world has ever seen – the Great Financial Crisis out of the U.S. housing bubble of 2003-2007 – Loan to Value ratios exceeded 90%.

I guess a sort of simplistic way to say this is that equity-funded corrections can be “severe mis-pricings,” but BUBBLES are debt-funded – both in their historical description but also in their systemic impact.

Semantics?

If someone pays $100 for something worth $50, does it matter if I call it a “bubble” or not when they take a 50% loss on their purchase? Probably not. But there is a reason why this vocabulary matters. As a general rule, equity-funded (unlevered) mal-investment has an expiration date to its impact – once one marks down the asset, the pain ends. Whereas in a “bubble,” there is a negative feedback loop at play. I don’t want my friend to lose $50 on his purchase, but his $50 loss on a single bad investment (with losses isolated to the capital purchase he already made) do not lead to losses in what I am doing, or you are doing, or the society is doing. They do not set off a chain reaction where other assets have to be sold to meet the debt requirement of what someone else was doing, bleeding over into other asset classes. They do not threaten the solvency of the lenders themselves, or counter-parties, or inter-connected financial players.

In short, a “bubble” is never really isolated. A mere “bad investment” often is.

Productive vs. Unproductive

One of my very favorite economists and influences, Louis Gave of Gavekal Research, wrote a piece a month ago delineating between productive and unproductive bubbles. The aftermath of excessive prices in assets that produce something (he uses railways and broadband lines as an example) is much different than excessive prices in non-productive assets (perhaps crypto fits that bill; certainly 13 years ago, subprime mortgage bonds did).

In other words, a group of pundits looking at assets and indiscriminately saying “that is overpriced” or “that is overpriced” does not tell us if we are in a bubble or what such a bubble really means. The funding of the asset (debt vs. equity) and the nature of the asset (productive vs. unproductive) matter a great deal. Pundits will have to do what they hate doing more than anything else – actually work.

State of affairs

There are high valuations across the globe in most risk assets. There are unprecedented low levels in comparative risk-free assets providing prima facie rationalization for much of that boosted valuation. There are reasonable valuations in many risk assets – but few that are “cheap.”

One will not know if current crypto prices prove to be “bubblicious” until the gift of hindsight comes. If the only reason to buy something is that others are doing it, or there is a momentum wave to be caught, that strikes us as poor rationale. But many things that seemed overpriced at the time (leading electric car makers) became more understandable in their valuation metrics years later.

Hindsight is always 20/20.

So what to do?

I will be concerned about a “bubble” when I see a system-wide disregard for risk and logic. Right now, I see plenty of governors against that. I see a rotation into value from growth. I see air coming out of the tech tires. I see stupid unicorn valuations being rejected. I see discrimination in the IPO market. I see some form of logic being applied to buys and sells.

Do I see over-valuation? Of course. In certain securities or arenas, there is froth.

But the cultural milieu does not feel like a bubble; dare I say, it feels afraid of a bubble.

What to do? Be discerning, be selective, and do not be afraid of missing out. Not buying something that goes from 50 to 100 is a whole different reality than buying something that goes from 100 to 50.

Invest and select inside a plan – inside an allocation – inside a rules-based portfolio construction that honors the big picture of goals and objectives, and outcomes.

Just the facts, ma’am

The aforementioned Louis Gave shared this quote recently (from a small-cap money manager he knows): “Should an investment narrative become particularly disputed, the best course of action is to identify the camp that is more emotional, and bet heavily against them.”

This is perhaps one of the most useful ways to view all of this. There should not be any emotion when it comes to discussing valuations. When heavy levels of emotion are required to defend a valuation position, that might just be indicative of a bubble.

The simplest way to sum it up

At the end of the day, I think the term “bubble” is almost a MACRO term – one that applies to a broad set of assets or asset classes, that reflects an almost society-wide psychology. The BUBBLE of dotcom/tech was a cultural phenomenon as much as an economic price one. It was defined by an utterly systemic disregard for risk and callous dismissal of mathematics and economics laws. It was memorialized by commercials and celebrity endorsements that infantilized the concept of investing. It reflected a mentality that I couldn’t define, but I knew it when I saw it. And it was bubblicious.

A few years later, the housing crisis was no different, though it suckered more people in because dotcom just involved bragging at cocktail parties about how much money you had just made. The housing bubble involved a 24/7 display of your bragging – you lived in your trophy, which fed the envy and covetousness necessary to accelerate the negative feedback loop. The “bubble” was not merely the ungodly amounts of leverage, the silly underwriting, the disconnect from cash flow feasibility to payment expense – the “bubble” was in the society-wide mentality that real estate never went down in price, that protective equity was a concept for dinosaurs, that there was no reason to care about principles of logic, math, and wisdom.

On the margin, one can overpay for an asset without it being in a bubble. Overpayment is often a bad investment (or an “early” one, in the fortunate cases). But a bubble speaks to a cultural mentality of mindlessness. It’s the best delineation I can offer.

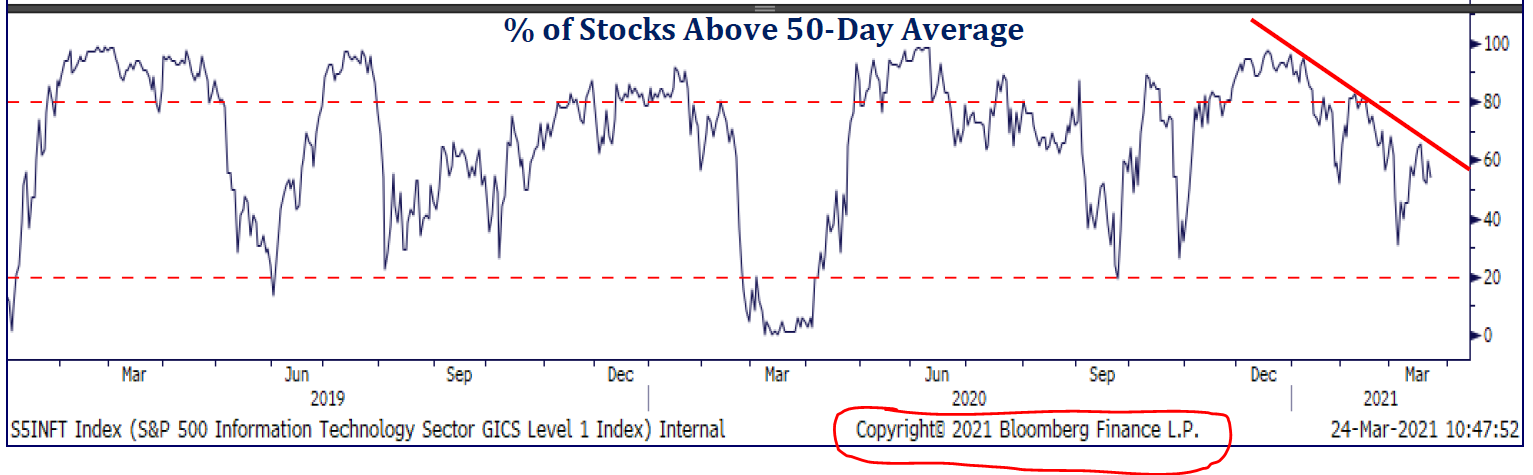

Chart of the Week

Even within the tech sector, selectivity matters. All tech stocks are good in a period of thoughtlessness. Some tech stocks are good in a period of discernment. Be discerning. And do not be afraid of missing out.

Quote of the Week

“A mania first carries out those who bet against it, and then those who bet with it.”

~ Jim Rogers

* * *

I hope this topic has been practically useful for you. Reach out with questions and comments. Watch some college basketball this weekend. And be discerning. To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet