Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

There is a strong possibility that many of you reading Dividend Cafe this week will be completely unaware of the subject I have chosen for this week’s topic. I do not mean you will be unfamiliar with the concept or will find the investment vocabulary tricky, or other such things that may very well happen from time to time in the Dividend Cafe. I mean, the actual event that I am writing about may be totally foreign to you, despite the fact that it has dominated financial news for five or six days now. There is a good reason for this if, indeed, it is true for you. The “news” story of which I write has proven to be a really weak “news” story in my mind (not for lack of trying), but even apart from the broader news hype, it has further proven to be a weak “financial news” story, and that really, really comes not for a lack of trying.

So why would I choose a failed news story and failed financial news story as the subject of the Dividend Cafe?

Well, of course, for many of you who are cursed with following the day-by-day hype machine of financial media, it will be a story you have followed closely, and a story that warrants some truth-telling and practical application. But even for the wider audience of Dividend Cafe that has no idea what I am talking about (yet), this story begs for us to address the subject of “contagion risk” – the general concept of something in financial markets that seems to have nothing to do with us whatsoever, yet via the concept of contagion – of one person’s risk spreading to others – poses a threat to us nonetheless. This week’s melodrama posed no contagion risk whatsoever, yet you wouldn’t know it from following the news all week.

After reading today’s Dividend Cafe, you will know so much more.

What in the world happened?

Last Friday afternoon, after the market close, I was receiving some pop-ups, alerts, texts, and tweets about significant market distress, about huge selling pressure, and referencing real market price distortions. I assumed I was reading something wrong because my screen showed the Dow having closed up +450 points that day, which was accurate. It had been a huge up day in markets, across all three major indices, and generally speaking there wasn’t a sign of distress anywhere.

Over the weekend, it became more clear that there was some heavy volume of selling in a few select names (not ones that are totally obscure and unheard of, but not names anyone would think of as indicative of the broad market). And certainly the volume of quick selling in some of those names, in the context of a big UP day in markets, indicated some pretty isolated and idiosyncratic issues. Well, if I hadn’t received another report, another Bloomberg headline, another alert, or another piece of news, I would have known right then and there what was obvious for the world to see …

Some over-leveraged sucker got his face ripped off. Or in less academic terms, a hedge fund had been margin-called. Period. Simple enough. Huge, massive selling into a down tape on a stock with no event-driven news to accompany – let alone while the rest of the market is humming along just fine – simply doesn’t happen unless someone is unwinding a position, and by “unwinding a position” I mean, “having a position unwound for them.”

But here’s the thing – I DID receive more headlines, more alerts, more texts, more news, etc. And all of it DID confirm exactly what I just said. Only this time, the focus of the entire weekend was not on the isolated hedge fund (or whoever the financial actor was suffering from the margin call), the focus in all media communications was:

(a) The impact to the underlying banks who were selling out the leveraged positions, and

(b) The threat this posed to the overall market

I am going to come back to both A and B in just a moment, but I first need to actually explain what really did happen to this isolated financial actor, and better answer the headline question above.

Archegos Who?

Allegedly, a private investment firm of a family office in New York office was at the heart of this escapade. The multi-billionaire proprietor of the firm (Archegos Capital) was a former hedge fund manager at one of the largest hedge funds in history, Tiger Management, and a known philanthropist in New York who I have actually met and spent a little time with on a couple of occasions. That virtually no one had heard of the individual or his investment firm is basically at the heart of why this story is the subject of Dividend Cafe. For how in the world could a man and a firm no one has heard of actually represent a systemic risk to financial markets? How in the world did this represent the possibility of mass contagion?

Well, the answer is, it didn’t. And it doesn’t.

But while I believe the attempts of the media this week to make the travails of this over-levered financial player a contagion risk story to all of us to be an utterly silly failure, it obviously was a story of deep financial distress for this entity. And we can’t know the exact details of the financial positions and sizes and losses here, because these things are not a matter of public record. What we generally know is that a couple of large U.S. media company positions and a few large Chinese internet companies were held in size – meaning, huge, huge positions – levered significantly (lots of borrowed money supporting an out-sized position relative to what had actually been paid for ) – and as the positions experienced some downside pressure it led to forced selling, and that forced selling led to more downside pressure, which led to more downside pressure, which then blew a hole in the bottom and led to this investment firm’s blow-up.

The story is a tad more complicated than just that because like most brilliant psychopaths, the use of generic huge leverage is never good enough. One must surround their rank irresponsibility in a cloud of obscurity and complexity as well, so much like the mortgage mess of 2008, straight leveraged buying is inadequate. We need complicated derivates and swap contracts to really beef up the drama, to make sure my readers’ eyes glaze over, and to ensure that no one will really ever know exactly what happened when a few billion dollars of borrowed money disappears from thin air.

But at the heart of this was something called a CFD swap, a “Contract for Difference,” where one can use a derivative for exposure to an underlying stock without ever owning the stock, have massive leverage in the position, put up collateral with their counter-party as needed, and not have to disclose the position in quarterly 13F filings (because the actual underlying company is not really owned). These derivatives are not exchange-listed, meaning they trade privately “over the counter” between parties, quite opaquely, and frankly, are a tiny part of global financial markets.

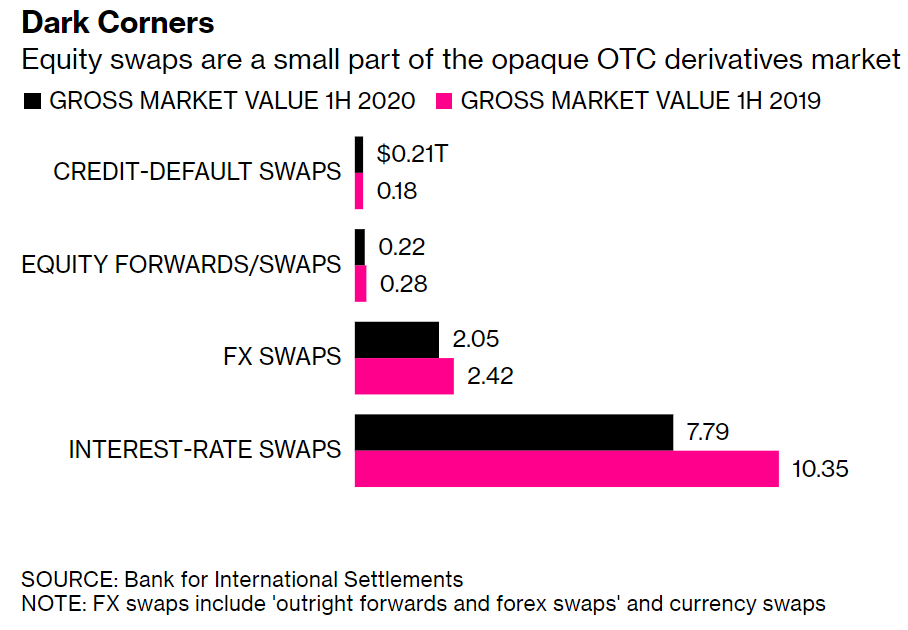

There are over $10 trillion of global swap contracts linked to interest rates, and $2.5 trillion of swaps linked to currencies, as various financial actors hedge rate risk and currency exposures all the time. But there is not even $300 billion, soaking wet, in equity swaps, worldwide.

The numbers being thrown about by media reports suggest losses from $5 billion to $20 billion, and because the banks were forcing the selling and are talking about some losses they will take, that suggests (well actually, it requires it by definition) that if the bank who loaned money to a leveraged purchase is taking a loss, the investor themselves suffered losses of 100% (and then some). So whatever the total “equity” was (the paid for part of the trades in question), that money is gone, and then even some of the “debt” portion (the borrowed money to pay for the rest), was lost.

We likely will never know how much money was lost, and even by whom. Meaning, to the degree some of this investor’s counterparties (large Wall Street firms, some local but apparently the two largest being a European bank and a Japanese bank) did suffer losses above the value of their recoverable collateral, I do not think they are going to advertise to the street the specifics of their losses.

But we know this. A private investment firm blew up, and now has a negative net worth. Some lenders to this investment firm took losses.

And the world continues to turn.

I am not making light of this, the market is

I mentioned already that on the day this was going down, the market was up 450 points. After a weekend of hand-wringing and headlines like, “Traders gripped to their screens Sunday night awaiting painful market opening” – the market was up a hundred points on Monday. It’s been flat to down a hundred points or so since, and as of my press time here on Thursday morning is pointing to a positive open in markets today. So we no longer have to speculate as to whether or not there is a systemic risk in what is going on, or what the contagion effect to this hedge fund’s demise is. That has been answered for us – it was a nothing-burger – a big donut – a complete joke of a week of media coverage, strong on click-bait, and devoid of real substantive coverage.

In other words, it was their business model just playing itself out. A normal week. Nothing to see here.

But could there have been a problem for us?

I actually did make this the subject of Dividend Cafe for a bigger reason than merely informing you of the events of Archegos Capital Management. I do want my clients to understand how contagion risk does actually work. Don’t get me wrong – there was not contagion risk here. A private party took really risky bets and suffered for them. Another private party (or two) facilitated those risky bets and will experience some degree of suffering for them. And that is what makes a market. I do not mean to be non-sympathetic to the families of employees of the investment firm that has experienced this blow-up, but it is not contagious. I PROMISE you – a HUGE portion of the money lost by this fund was previously made via the same leverage that did them in. They knew what they were doing. It blew up. I would add more to the story if there were more to the story, but there isn’t.

But this is not the same as me saying I do not believe in contagion risk. I certainly do. This just wasn’t it. And, there are two levels to “contagion risk” that are really quite different from each other. We need to delineate those two.

Contagion A and Contagion B

The media is never going to do you the favor of separating these two things, but they need to be separated for you. For our purposes, Contagion A is when things happening in one corner of financial activity substantively erode the value of things happening in other corners. It is real. It is painful. It is fundamental. Of course, it is always and forever linked to excessive debt and leverage, but be that as it may, the solvency of the U.S. mortgage system was a pretty darn contagious event. The set of dominoes involved and how deep and wide they went touched the vast majority of global financial actors. I hope I don’t have to re-visit that for you. And frankly, there was pretty real contagion risk in the European debt crisis of 2010-2013. Those concerns made a lot of sense, too. Again, I can unpack that more if you wish.

But Contagion B is where there is “noise.” Where the events of one actor lead to some volatility in another actor which leads to a few days of market funkiness in a bunch of areas but doesn’t erode balance sheets, doesn’t impair P&L’s, and simply doesn’t last. The Gamestop/Reddit/meme stock hubbub of late January maybe reached this level. Noise. Headlines. Some algorithms triggered. A little action. But nothing else.

A whimper without a bang.

Media malpractice

This story was neither Contagion B (temporary market volatility as headlines ran their course) or Contagion A (substantive losses that domino throughout financial markets). This story was isolated and silly. But even in the case of a real Contagion B story, the media will never make any effort to differentiate it from a Contagion A story. That is our job. And investor decisions in Contagion B stories are the things that derail financial plans. Avoiding that is our job. Obfuscating these things is the job of the press.

Where it could have gone but didn’t

So a very wealthy private family office gets way, way, way over their skis in a leveraged trade. Their banks lose money. It’s a few billion dollars, which for our family budget is a lot of money, but for the purposes of global financial markets is not even couch money – it is lint. This private investment firm, as best we know, didn’t even lose other investor’s moneys – just the money of their own family office.

Regardless, these losses, while unfathomable to most of us, and inexcusable for responsible adults, are not systemic, contagious, or even relevant to the rest of us.

But Long Term Capital Management in 1998 was (sort of). And other domino capital events have been. Why is this different?

Size – it isn’t that big

Exposure – there is limited counter-party risk

Diversity – it is multiple banks, not all the risk on one

I would suggest that MOST events politicians say need further regulation or the media says “could tumble financial markets” are, in actuality, private events where the reward potential and the risk potential is borne by the actors involved in the transaction(s). I don’t merely suggest this – I declare it, because it is true.

Worst case, there are “contagion B” events that merely create noise in markets – create volatility – allow for hype and activity – yet in the end, do not alter the health of financial markets, do not change the profit-making capacity of well-run businesses, and do not sustainably impact credit markets or spreads.

In other words, here is your exposure to events like what happened this week, or even potentially worse ones:

(A) None, or

(B) A test of your resolve for a few days

If anyone of us fails in B, we are the bearer of that risk. Just like the levered family office is the bearer of theirs.

The crisis of responsibility comes to investing. We intend to win it. To that end, we work.

Chart of the Week

A little context on the size of the worldwide swap market

Quote of the Week

“Having a large amount of leverage is like driving a car with a dagger on the steering wheel pointed at your heart. If you do that, you will be a better driver. There will be fewer accidents but when they happen, they will be fatal.”

~ Warren Buffett

* * *

We hope you will join our national call on Monday to discuss all things Q1 in markets. In a lot of ways it has been a boring year so far, but in other ways, there’s needle-moving things happening that need to be discussed.

DC Today next Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday (I will write the first three from NYC and on Thursday Brian Szytel will deliver the goods). Next Friday’s Dividend Cafe topic is TBD, but I am predicting something captivating.

I truly do wish you and yours a very Happy Easter weekend. History has never been the same.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

dbahnsen@thebahnsengroup.com

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet