Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

As I am out of the country these last few days with my family on a brief trip as the kids enjoy a week out of school, returning today, I am doing this week’s Dividend Cafe “old school” – which is to say, jumping around topic to topic and answering a handful of questions along the way. I love the “single topic” Dividend Cafe writings each week, but every now and then, it is fun to mix it up a little, especially from a top-secret overseas destination!

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

Fed rate estimations

Has the recent “less than anticipated” disinflation with the Consumer Price Index and the Producer Price Index changed the outlook for what the Fed will do in its next one or two meetings? Is an actual half-point rate hike on the table again for the next meeting versus the quarter point widely anticipated? As of press time, the futures market has a 79% chance of a quarter point and a 21% chance of a half-point, and with bond yields having moved modestly higher in the last couple of weeks, I think some of that short-end tightening was done for the Fed by the market. The 6-month yields and 1-year yields (Treasury bills) hit 16-year highs last week. The two-year is right in that range as well.

We have had a couple of hawkish Fed governors saying they wanted 50 basis points (Bullard and Mester, both of whom do NOT vote in the FOMC), but the rhetoric from the Fed has been pretty clear that they are looking at 25 basis points at the next meeting.

There is currently a 73% chance of another quarter-point rate hike at the May FOMC meeting (which would bring the Fed Funds rate to 5%, where I believe they will stick once at that point).

Bitcoin vs. the Dollar

A thoughtful reader asks:

“When speculation goes up, Bitcoin goes up. When speculation goes down, Bitcoin goes down. Point taken. But the Eisman example of the store owner’s trust in the dollar still doesn’t seem to hold weight. Isn’t the store owner’s trust in the government which backs the dollar? When that trust fails the dollar will become worthless to him. Now of course I understand it isn’t at all probable that the US government will disappear overnight and that makes Bitcoin way more of a speculation at this point in time. I’m still struggling to understand why Bitcoin is a shiny object-Austrian pipe dream vs real private currency. Do you think private currency is possible?”

The store owner’s trust in the dollar is a trust in the stability of the medium of exchange. If one accepts $100 of dollars for a product today, they would like to believe it will be worth $100 five minutes later and probably even five days later. That confidence in the medium of exchange is, whether self-conscious or not, a reflection of the government that backs the dollars, and I am quite sure it is almost always not self-conscious. That government, in the case of the dollar, has the power of the state, the legal monopoly on violence, and the largest military in the world, as it goes about with legal taxing authority on the largest economy in the world. So yes, I believe most feel pretty confident that the dollar, as an extension of the faith and credit of the 250-year default-free U.S. government armed with the military, taxing authority, and the biggest economy in the world, will continue to function as a medium of exchange. But your question is whether or not a private currency is possible, and my answer is: As long as the government with the military and taxing authority are willing to let it exist, it can exist. But if a currency’s private existence is dependent on the government allowing it to exist, is it really private? And as a medium of exchange, if it lacks the preconditions of stability, it remains a speculative trading vehicle and a tool for rank criminality, but it is not a currency.

As for it serving as a hedge against the inflation and erosion of purchasing power we experience year by year, we got our answer the last year as to how bitcoin functions as a hedge against inflation, and we got our answer as to how gold does in that context for the last 43 years. Those things were empirically, not theoretically, answered.

Finally, I want to correct one other assumption in your question: It is not an Austrian price dream. I understand some who claim to be Austrian have drunk the kool-aid, but the Austrian logic on these matters always believed in an underlying asset of value (contra fiat money) be used as a medium of exchange (that is, that money itself was a commodity to help facilitate the exchange of other commodities, hence the heavy bias towards the gold standard in many Austrian camps). Bitcoin is a non-governmental fiat whose differentiator is that it is held in a ledger. So I am sure some may like the technology better, but that has nothing to do with it being Austrian in any form of true ideological application. I have many sympathies with the Austrian school in terms of praxeology and basic economic methodology and commitments and yet have always rejected bitcoin as a medium of exchange out of hand.

Producing more without people

Some have asked questions in recent weeks about the “Japanification” thesis that we are seeing economic growth suffer behind excessive debt and now adding demographic challenges on top of that. The basis thesis (more or less a tautology) is that G = P1+P2, that is, Growth (economic growth) equals population growth + productivity growth. Produce more, have more people, and see more growth. That algebraically means there are two variables at play towards economic growth. One reader asked:

“But my question is this: while this nation’s debt, deficit, and socialistic ideology seemingly require perpetual and exponential population increase; on a purely economic level, could it be posable to have economic growth simply by increasing production via technology? And naturally consumption would take care of itself via elevated living standards?”

And so the answer is all at once, “yes” in a mathematical sense – if you got a higher P1, it would offset a decline in P2, but over time a declining P2 hinders your ability to get a growing P1. Do we all agree that we have had a pretty dynamic twenty years of technological innovations? Like, the most advanced, accelerated advancements at the most rapid rate in human history? Yet economic output is stunted, and we have seen Japanified growth for 15 years. Now, it is unfathomable to think about how much worse it would be without the benefits to productivity much technology has offered, but the point is that it is not able to overcome a burden as large as what we face.

I believe the data is clear that technology made us more productive and efficient in the 1990s, but that afforded us the ability to get “the same with less” as opposed to “more with the same.” Improved productivity from technology-facilitated less effort, which is a standard part of the utilization and adjustment cycle.

At the end of the day, the answer comes down to how heavy ankle weights we want to wear while we run. Can a runner just pick up the pace to account for the extra weight he or she is carrying? I guess so. But isn’t there a pace that becomes impossible to maintain once a certain weight is being carried?

What would you do?

One reader chimed in:

“I’m curious, given that Japan hasn’t been able to dig itself out of its own mess, what solutions do you have for that problem? What would be the better way to run their economy?”

I suppose I would rather answer this applied to the American economy than the Japanese one for the simple reason that I am an American, I live here, my economic interests are contained here, and my economic legacy for my family is largely here. And most of all, the client capital I steward is almost entirely domestically domiciled. American economic dynamics are my professional and personal interests. And yet, I have used Japanification as a crucial global precedent to set the table for what is playing out in America, so I see the parallels in how one looks at these things. But, what Japan ought to do now, and what the U.S. ought to do now are not entirely the same. Their respective positions, resources, cultural realities, and economic situations are different enough that a policy prescription must look different.

That all said, they both face excessive debt-to-GDP ratios. I would recommend, in both cases, balanced budgets going forward, which can only be done at severe political costs. In the U.S., it would mean people losing elections. In Japan, it would mean people becoming unpopular. But it is what I would do. It is just the basic starting step to the entire deal – “when you’re in a ditch, quit digging” type of thing. That is table stakes to start the process of reform.

Before I did that, or the next ten things I would do, I would never, ever, ever, ever, ever stop talking about the fact that re-achieving economic growth is the only cure to our problems and that there will be some pain as we sort through this to avoid a worse pain later. I probably wouldn’t use the analogy of how a hangover after one night of drinking is better than a hangover after a 5-day bender, but I may whisper it for others to use the analogy.

I should point out this can’t really be answered from the vantage point of politics. All of the things that need to be done will be unpopular, and unpopularity is incompatible with politics (get unpopular enough, and you get unemployed in politics). I do not know if the question is meant to appeal to my ideological and economic prescriptions (all I care about) or political and practical ones (a domain I will never, ever, ever be in).

But with all that on the table, I would generally create a resolution strategy around:

- A rules-based monetary policy that was not overly restrictive but not so easy as to exacerbate the problem would HAVE to be implemented

- Amendments to central bank objectives that restored their role to “lender of last resort”

- A balanced budget to stop the bleeding of debt-to-GDP explosion

- This balanced budget will not happen without spending cuts across the board

- This balanced budget will not happen without entitlement reform

- A growth agenda that leans into creative destruction, not away from it

- Full expensing of all capital expenditures

- Flatter tax rates on earned income

- Earnest and grown-up aspirations for deregulation – responsible, prudent, needle-moving deregulation

- An unending focus on price discovery and capital allocation that pushed and incentivized capital into its most rational use

- I strongly suspect a Value-Added Tax (VAT) is coming on the other end of all this if we are to reduce the principal of debt overhang

The journey to a place of higher growth and restored fiscal sanity is NOT going to happen the way I would do it in Japan or the U.S., so I have always hesitated to provide even a high-level framework like this. The central banks WILL become more interventionist, not less, and they will pursue more creative ways for central banks to soften the fiscal edges of budget imbalance, not less. There will be MORE yield curve control and MORE quantitative easing, not less. And there will be other creative interventions no one has currently thought of, not an unwinding of current interventions I do not like. Any number of things can and will play out in the future, and I have written at great length as to why I believe those things demand greater portfolio quality and stability, not speculation or “dependence on the generosity of strangers.”

Population Deflation = Price Inflation?

One reader wanted to know if a reduced population would be deflationary (as it has obviously been in Japan) or inflationary (because there would be less production).

“From what I’ve understood, declining populations across the West should have a negative impact on growth through reduced productivity of the smaller workforce and also reduced savings/investment. However, wouldn’t this have an inflationary effect if there’s too much money chasing too few goods (reduced productivity)? Or should I see this as reducing the money supply to the extent that there will be less consumers and more goods, therefore resulted in disinflation/deflation?”

The issue is not just top-line demography but the specifics of the age group alterations. A population with X and a population of 2X also have to be evaluated for their composition – that is, their make-up of seniors (mostly consumers with limited production), their prime working age (mostly producers with limited consumption), and their very young (most consumers with no production).

We call this the dependency ratio, and it deals with those dependent on the production of others for their consumption, divided by the total population. Look at it this way – those > 65 and those <18 divided by the total population is a good way to do a back-of-the-napkin dependency ratio. A higher dependency ratio generally means lower tax revenues, higher government spending, and, therefore, larger deficits. And I believe deficits misallocate capital and stunt productive capital formation – ergo, prove to be deflationary over time.

There are very legitimate debates about how this impacts the supply side relative to the demand side and intersects with inflation vs. deflation. I lean to the disinflationary side because (a) It has historical support, and (b) I am more confident in the ability of technology and entrepreneurs to grow production than I am in a declining population base to increase their consumption (let alone their savings rate needed to capitalize the production that will be needed for a shrinking working-age population).

P.S. – My focus on demographics goes beyond population size but looks to labor participation force, productivity, able-bodied people working vs. receiving transfer payments, training and vocational development, marriage age, fertility, divorce rates, household formation, and more. All of these issues intersect with economic growth.

Long-term goals don’t work with short-term solutions

A reader asks about the current market conditions and nice yields for short-term treasury bills.

“I have a question in regards to CDs and Treasury bills. I’m wondering with the instability of the stock market if CDs and/or T-bills are a reasonable short-term investment at this time to diversify a portfolio?”

And for this, I will save my word count in this edition of Dividend Cafe and merely point people to this popular edition of the Dividend Cafe from last year, where I walked through the need for growing income year by year, and this edition where I explained the pros and cons in higher yields in the bond market.

If the objective of the investor in the above question is to “wait until stock markets no longer go up and down,” they will be waiting for all eternity. If it is to wait until stock markets go up in price, that strikes me as counter-productive. If it is a question, though, about short-term needs for cash, yes, I would never put capital in the stock market where the principal is needed back in the short term.

Some quick other takeaways

- Appreciated Louis Gave of Gavekal Research (I always do) pointing out last week – there are ample reasons investors are mad they exited their Chinese investments last year (it was the politically right thing to do last year, and much of China’s situation and tech crackdown seemed un-investible). Yet now their currency, tech stocks, and more are rallying, and there is seller’s remorse, yet the stigma of being in the world’s most controversial market is troublesome, just as not being exposed to the largest macro story of 2023 (China’s re-opening is). How does an institutional investor reconcile this tension? Copper, other Emerging Markets, Japan, European exports of luxury goods, etc. China-adjacent for that investor who knows it sounds bad to say, “I am invested heavily in China”

- In a short-term or mid-term period, it is never good enough to assess a boom, a bust, or a flattish environment – one has to assess the reasons for the boom, bust, or flattishness if they attach a bona fide investment thesis to the forecast. A disinflationary boom is different from an inflationary boom, and the same can be said about busts as well. The “four quadrants” at play here with booms/busts and inflation/deflation are useful for thinking about appropriate solutions in each, though “flat” eras require different solutions all together. You will be shocked to know that there is nothing that proves to be more “all-weather” than dividend-growing equities in each potential scenario, which is helpful given the sheer impossibility of calling correctly in each era, both the boom/bust/flat diagnosis and the nature/causation of it.

Chart of the Week

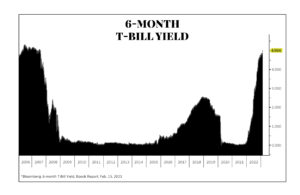

I guess I just picked this chart to show you how messed up things have been and are. This is the yield of a six-month Treasury bill going back to a few years before the financial crisis. It almost perfectly tracks the Federal Funds rate (the Fed has great but not direct control over the short end of the yield curve). Things had gotten pretty high pre-crisis, and before the GFC launched and credit markets were clearly breaking, rates began their descent, eventually getting to zero and staying there for what felt like a lifetime. Then the Fed began to normalize before chickening out in late 2018. Then they started heading lower again, and then COVID came, and they really went back to zero. And now here we are again, back to the pre-GFC high-level mark, having gotten there with a bang, not a whimper. You will note the lack of subtlety or gradualism in any side of this. Whipsaws higher and lower, like a boom and bust cycle instead of any semblance of monetary stability.

Quote of the Week

“I mean to live my life an obedient man, but obedient to God, subservient to the wisdom of my ancestors, never to the authority of political truths arrived at yesterday at the voting booth.”

~ William F. Buckley

* * *

I will be back stateside by the time you are reading this and am already excited for another week in the office (California Monday/Tuesday next week and NYC for the rest of the week after that). February comes to an end next week. In the meantime, reach out with any questions whatsoever. Heck, they may even end up in a future Dividend Cafe! =)

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet