Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

“Bubbles” are not easily defined in financial parlance, but as Justice Potter Stewart once said about something else, we “know it when we see it.” The hard part of knowing that we see a bubble, though, is often that we are having the conversation after a bubble has burst. That is weird, right? A bubble is easier to identify when it is no longer a bubble but rather a pile. In nature, a bubble is air trapped within a thin layer of water. When it bursts, the bubble is no more, the air is freed, and the liquid evaporates. Financial bubbles are a little different because something may still be there to identify when the bubble bursts (but not always).

Perfect parallels between molecular bubbles in the physical sciences and the language of financial bubbles are not possible. But what is possible is to understand the history of manias, the role of human nature in such speculative excesses, and how investors ought to think about the risks and rewards of this whole subject.

Today, the Dividend Cafe jumps into one of the most important subjects in all of investing – and I do not just mean in the modern era. Bubbles did not start in 1980s Japan or the 1990s dotcom incident. Rather, speculative manias have existed since time immemorial. This is because human nature is immutable. What can change, though, is our understanding, preparation, behavior, discipline, and anti-fragility.

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

Never as Silly as My Beanie Baby Analogy

I use Beanie Babies a lot to illustrate the magnitude of insanity that can be involved in financial manias. A $5 toy that cost a couple dollars to make was selling, in some cases, for thousands of dollars, behind the novelty of EBAY, the easy-to-manipulate realities of supply and demand, and the fact that a whole lot of people in the world should not be listed as your emergency contact, if you know what I mean.

But it is a “reductio ad absurdum” of an analogy, meant to take one of the most extreme cases of human irrationality to make a broader point. It is not the norm of human excess. Now, human excess is the norm – that is, irrationality and greed and euphoria are all incredibly common. The immeasurable rage people feel when they see someone else getting richer than they are drives a significant amount of human activity. But if I am being fair to most “bubbles” in finance history, many of them started with a more plausible story than an ugly stuffed toy. Well, not all of them, I suppose. But it is not helpful to make the point I want to make in this commentary if I treat all speculative manias like Beanie Babies. Human nature is immutable, yes. But sometimes the product involved is more commercially attractive than others. Fair enough.

The South Sea Bubble story centered around vast trading profits between economic superpowers. The prices being paid and the uncertainty in the endeavor became unsustainable, and the final result was insolvency for as brilliant a mind as even Sir Isaac Newton, but at least the project itself started off as something that could make sense.

The dotcom story of the late 1990s is easy to caricaturize today, and cultural laughing stocks (pun intended) like Pets.com and other absurdities of that era are certainly deserved punching bags to mark dotcom imbecility. But let’s not forget that the basic idea did prove to be correct – that we were in the early innings of a paradigm-shifting moment in world history, where a substantial amount of personal and commercial activity would move to an online world, and where trillions of dollars were going to be made. Should companies with no revenue and a business model designed by a few drunk kids in college command multi-billion valuations, and take over Super Bowl commercials for a few years? Obviously not, but there was a real industry story at the beginning of this and the end.

The perversity of housing costs from 2002 to 2007 is all the more ironic now in that virtually all of those homes now trade more than they did in their bubble peak. Granted, that was made possible by the forced liquidation of the debt behind it, and two decades of easy monetary policy, government subsidy, a multi-trillion dollar takeover of the world’s largest mortgage lender, and about six other interventions that drastically changed the story. But my point is, no matter how over-priced Vegas condos or Florida houses were in 2006, they were, you know, real places to live.

My first point is that a bubble is not defined by the preposterousness of the underlying asset. Bubbles can materialize out of that which is brilliant, average, and yes, utterly asinine.

In Fact…

Technology, in particular, is highly likely to present extremely attractive, investible, and exciting opportunities. That is because human beings are capable of extraordinary innovation. We were created with a boundless capacity for productivity. This manifests itself in extraordinary technologies at times that change human living, and present an abundant return on invested capital.

Sometimes great technologies become obsolete. Sometimes they do not hold competitive advantages. Sometimes they fail. But oftentimes, true benefit to society is achieved, and yet the investible universe of the space becomes highly precarious from an investment standpoint. How can both of these things be true at once?

Supply. Demand. Valuation.

The less supply of capital to exciting technology, the more attractive the future returns. The greater the supply of capital without a proportionate increase in investible ideas, the worse the returns. Supply and demand intersect and move up and down their respective curves, impacting valuation. And the entry point of an investment (valuation) is a significant factor in the return of that investment.

In All Thy Making, Make Money

Companies cannot become long-term attractive investments if they cannot make money. A demo of a product that is jaw-dropping will not become commercially viable if there is no path to profits. Show-and-tell is not a monetizable event. Now, stock prices can reflect the hope or promise of a future profit path, but that just reinforces my point. Profits are the point of the investment, and if a company will never achieve a point of profitability, and furthermore, a profit level (and growth of profits) that rationalizes its market valuation, it will not matter how “cool” the product is. Markets, always and forever, eventually punish companies that lack coherent business models.

The dotcom world was highly plagued by the co-mingling of companies with cool websites that had no way to charge for their coolness besides obnoxious banner ads (most of them in the late 90s) and other companies that had entire ecosystems that oozed future money-making (Google, Amazon).

The post-2010 technology world has a lot of questions around it (valuation, future competition, regulatory apparatus), but it surely does not have the 1999 questions of the business model. To ignore the revenue-generating abilities of Apple, Google, Meta, and Nvidia would be insanity. That was not the case with the dotcom bubble. It was a double-whammy moment of excess valuation (to put it mildly) connected to companies that really couldn’t exist apart from primary equity capital. The primary equity capital was not a bridge to revenue; it was a substitute for revenue. All of that was one big “wait” moment for gravity to take hold. And take hold it did.

But the Real Point is not about Business Planning

We now have to start getting to the real heart of the matter for investors. It would be extremely naive to assert that the dotcom bubble was a case of investors doing flawed fundamental analysis. It isn’t like the average day trader in 1999 did a discounted cash flow analysis on Webvan and just underestimated costs or competition. No. One. Cared. At. All. It was pure, unadulterated FOMO. It was a hype machine wrapped inside a media bubble tied into an euphoric enigma. Webvan went bankrupt because it had no revenue. But Johnny did not lose his 50k ETrade account because Webvan had no revenue; he lost it because he was gambling with his 50k on something that he believed would go up for no other reason than:

- He hoped it would

- His friends said it was for them

- It had been going up

Other companies far more reputable than Webvan also set tens of billions of investor capital on fire. Yahoo was hardly Pets.com. But in 2017, Yahoo and AOL, put together, sold for $5 billion to Apollo – well less than the $220 billion they were once worth (and less than the $8 billion Webvan was once worth – ouch!).

The issue, whether it be low-quality companies or high-quality companies that become darlings of the public, is that investor decisions become divorced from analysis, value, and common sense. This is, always and forever, a beginning precondition for a bubble.

As the incomparable Howard Marks said in early 2000:

“People look to the share price for an indication of how the company is doing. Isn’t that backwards? In the old days, investors figured out how the business was doing and then set the share price.”

Symptomatic Behavior

I wear the label “fundamentalist” as a badge of honor when it comes to my fiduciary duties as a professional investor. The notion that an investor’s job is to “find a company that can be sold at a 1,000% profit” as opposed to “finding a company that grows earnings …” is not mere semantics – it misses the chicken and egg, badly. Too many believe that stock price gains are sustainable apart from fundamental operating performance, and they are wrong. Can one buy a stock low, not see the company execute over a long-term basis, but still exit at a high price? Of course. Can this trading-casino vision of public equity markets work in any sustainable sense? Of course not. Where this vocabulary and mentality surface, we see symptoms of the underlying issue that gives birth to bubbles: A cognitive disconnect from what creates wealth. Value is created out of high returns on invested capital and free cash flow that comes from well-executed business models. Believing that math is irrelevant, that discount rates do not matter, that earnings do not matter, that all of these things are obsolete – that investing returns are the aim and not the result of an actual company’s aim – these are the symptoms of a bubble about to be.

But This Time it’s Different?

One rationale for avoiding the tediousness of company fundamentals and embracing the excitement (and circularity) of “stocks that go up when they become popular” is that one can avoid the risk of being in a bubble when it bursts by … wait for it … selling before the bubble bursts. It is all so simple, you see! Ride the momentum to the promised land of riches, and avoid the carnage by exiting before the silly masses hold on too long. What could go wrong?

In reading an old Howard Marks piece, I came across this quote from the late Wall Street legend, Barton Biggs, whom I adored:

“The technology, Internet and telecommunication craze has gone parabolic in what is one of the great, if not the greatest, manias of all time … The history of manias is that they have almost always been solidly based on revolutionary developments that eventually change the world. Without fail, the bubble stage of these crazes ends in tears and massive wealth destruction … Many of the professional investors involved in these areas know that what is going on today is madness. However, they argue that the right tactic is to stay invested as long as the price momentum is up. When momentum begins to ebb, they will sell their positions and escape the carnage. Since they have very large positions and since they all follow the same momentum, I suspect they are deluded in thinking they will be able to get out in time, because all other momentum investors will be doing the same thing.”

Barton wrote that on November 29, 1999. I do not believe something more prescient has ever been written.

It is not different, then, now, or in the future. Buying on the madness of crowds, believing that you will be the exception to the madness of the crowds in time, is hubris that leads to portfolio calamity. I have seen it more times than I care to count.

Is Mag-7 or AI or Big Tech or Whatever a Bubble?

I want to make two things very clear about the two major bubbles I have lived through in my lifetime:

- As I said above, the dotcom bubble was a valuation/FOMO/atrocity, but it was also a fundamental disaster around a gazillion companies that had no business trading at a million-dollar valuation, let alone multiple-billion-dollar valuations.

- The housing bubble that led to 2008 was debt-fueled, period. It could not have existed apart from leverage. Excess credit led to excess asset prices, and the inevitable decline of those asset prices (without an underlying drop in absolute debt) led to a debt-deleveraging spiral.

And as critical as I often am about the valuations in today’s big tech/AI world, I do not believe either of those conditions applies to the current state of affairs.

Now, I am done yet. But let’s at least make these two points very clear:

- The Webvan/Pets.com level bubble of the dotcom era does not apply to Mag-7, because you may have noticed that these companies are not Webvan or Pets.com.

- The debt/leverage/credit conditions that have made up most bubbles in history are not visibly present in this current Mag7 moment. Do I believe the crypto world is reliant on debt fuel (borrowed money to drive asset prices)? You bet. Does some margin buying play into Mag 7 valuations (particularly with hedge funds)? Sure. But is there anything comparable in the leveraged nature of Nvidia ownership compared to Japanese real estate in 1987 or Vegas condos in 2005? No. Comparison.

So no bubble? Is it safe to proceed?

Not quite.

Here is the issue that makes this moment in time so difficult:

- The fundamentals of the businesses are amazing (cash flow generation, marketplace moats, competitive positioning, etc.).

- Yet, a half dozen companies making up over 30% of the S&P 500 is unprecedented, in fact, DOUBLE past precedent!!!

- The tech/telecom bubble of 2000 saw seven companies equal 22% of the market, right before they crashed and burned. 32%? It is hard not to raise your eyebrows.

- There does seem to be an “irrational exuberance” around this current AI moment.

- But Greenspan said that in late 1995, the dotcom crash came in March of 2000

- The biggest driver of investor behavior right now seems to me to be the worst possible thing imaginable: Fear of not owning something that your friends do own. “There is nothing so disturbing to one’s well-being and judgment as to see a friend get rich” – Charles Kindleberger. I have never seen or studied a period where this investor psychology, so heavily tilted to the greed and euphoria side of human nature, did not end badly.

- Many of these points I am making were true a year ago, or two years ago, though. And here we are.

I believe that objectivity and rationality are in short supply these days when credible investors try to rationalize current valuations. Our psychological leanings become flexible to accommodate what we want to be true of our portfolios. This is historically “bubble” zone thinking and behavior.

So, What to Do?

Is it possible the Mag 7 and AI world will crash and burn? Of course it is. That would be bad.

Is it possible the Mag 7 and AI world will not crash and burn, but will be subject to prolonged subpar or mediocre returns? Of course, and in fact, that may be a higher probability. And this also would be bad.

Is it possible that this world will continue to see above-market returns for years to come? Possible? Yes. Likely? No. A poor risk-reward trade? You bet.

And is it possible that they will rally hard from here and then enter the bubble crash environment we have seen in history? Blow-off top followed by carnage. Absolutely possible.

There are no scenarios listed above that I like.

A Wise Man Once Said

I have quoted the great distressed debt investor, Howard Marks, several times already, but allow me to do so again so as to capture some guiding principles that I think are crucial to the subject at hand:

- It’s not what you buy, it’s what you pay that counts.

- Good investing doesn’t come from buying good things, but from buying things well.

- There’s no asset so good that it can’t become overpriced and thus dangerous, and there are few assets so bad that they can’t get cheap enough to be a bargain.

If all there was to it were these three principles, I would have made a classic value case for buying well and offered a general mathematical warning about today’s nosebleed valuations in big-cap growth. But I think I am saying more than that. I’ll bring this letter to a close with my summary takeaways.

My Conclusions

- The current environment has “necessary but not sufficient” preconditions for a bubble. What is going on in investor psychology right now is always there before a bubble, but that is different than saying it assures us of a bubble.

- There is little regard for the fact that right now, competition and disruption are a two-way street. Market leaders do not always stay market leaders forever. And even if they do, an 80% market share that becomes a 70% market share is a significant downtick, despite maintaining impressive leadership. Our dynamic economy barely ever sees top companies stay top companies. ONE company in the Mag 7 today was even in the top 20 of companies just 25 years ago. 14 of the top 20 companies today were not in the top 20 then. That is how our system works, PTL.

- Appealing to the “facts of the case” is irrelevant when ascertaining investment merits. The tech and telecom predictions of the 1990s did happen. The investor results were atrocious. Great stories taken too far become bad investments. There are five hundred years of support for this.

- The Mag7/AI world has benefited from the index nature of ownership on the way up. Those exact same factors could harm them in equal proportion on the way down.

- There is only one principle I am more sure of in investing than the principle that “valuation matters” … And it is that when people start telling you that valuation doesn’t matter, it is time to remember how much the principle of valuation matters

- I do not know if we will one day consider this period to have been a “bubble” or not. I believe my Cisco/Nvidia example is worthy of note, as well. Fear of a bubble burst is a good reason to be cautious with this space, but it is not the only reason to do the right thing and construct a proper portfolio. The risk-reward trade-offs I describe apply even if we simply have muted returns or “valuation adjustments” in the space.

- I have seen crazier and frothier and more bubblicious moments than this. But that is hardly a ringing endorsement.

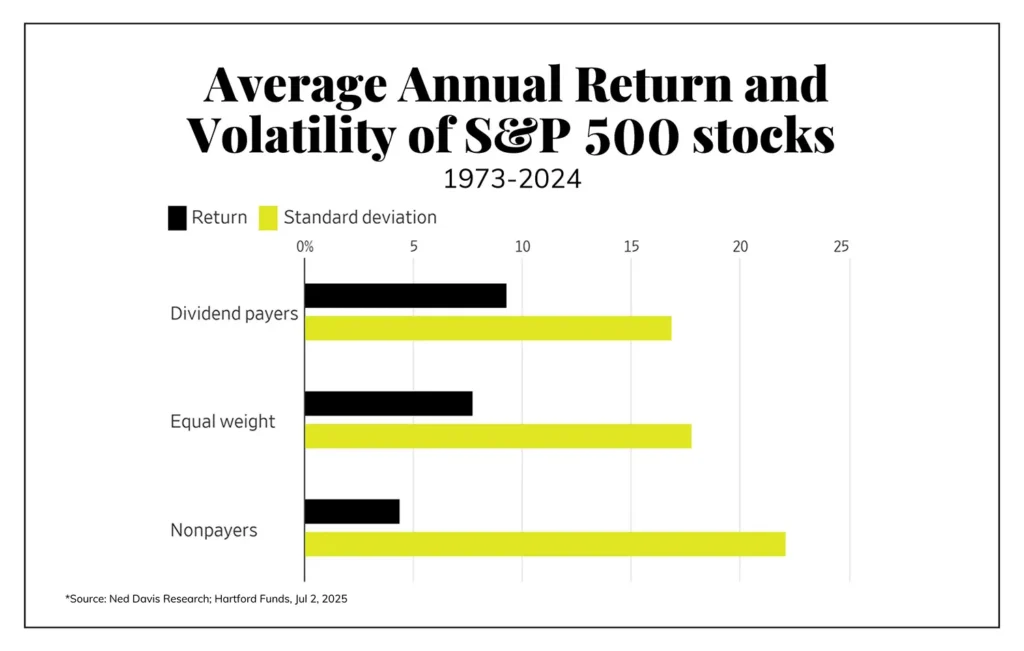

Chart of the Week

It would seem to me that this chart requires no additional commentary.

Dividend growth is not about what you give up for its superior attributes; it is about what you pick up.

Quote of the Week

“We are in the business of making mistakes. Winners make small mistakes; losers make big mistakes.”

~ Ned Davis

* * *

This Dividend Cafe went out on Thursday because tomorrow is July 4th, one of the greatest holidays of them all. Our nation celebrates 249 years tomorrow, and we all live off the fruits of that great tree, one that declared life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness to be the unalienable rights needed to sustain a nation. To these ends, we work. Enjoy your long weekend, and Happy Birthday, America!

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet