Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

On August 1 of this year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed at 35,630. As of early this morning, just a tad over two months later, it was trading just below 33,000 (note: by press time, the market had rebounded intra-day Friday). This is a -7.5% drop in about nine weeks, which we will discuss more in today’s Dividend Cafe. If -7.5% in nine weeks doesn’t seem like that big of a deal, it’s because it isn’t. However, what I didn’t mention is that almost all of that drop has been in the last three weeks (-6% of the -7.5%). The Nasdaq has fared a tad worse with similar timing in the numbers – a peak at the end of July, a slow drip down since, with an accelerated downturn the last few weeks.

The right thing for me to do in this period is probably not write about it. By addressing it, I enter the unavoidable territory of contradicting best behavioral practices around market downturns. And yet we exist to offer perspective, point-of-view, commentary, and conviction, and so to not address key market or economic activity would also be problematic.

The reality is that a -5% or -7% drop in markets (or more, for that matter) is a par for the course, standard, status quo, always-to-be-expected part of equity investing. I shouldn’t (and won’t today) write as if it is an urgency or source of panic in any investor’s life. The behavioral realities around market volatility should (and will be today) constantly reinforced. And at the same time, there are particulars in this stage of the cycle that I think are worth unpacking.

So today’s Dividend Cafe does it all today – it holds in tension the two things I most struggle with on these pages: the macro commentary of current events and the behavioral wisdom of how not to react to such.

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

Say everything three times

I wrote in last Monday’s DC Today that I believed there were six different reasons bond yields were flying higher and that isolating it to just one lacked nuance and due thoroughness. Others have chimed in with similar perspective. I stand by that analysis (of five whole days ago) and reiterate those six factors here.

- I am convinced that Quantitative Tightening is finally taking a toll on the long end of the curve. Every time QE has ended, the initial response was for declining long bond yields before eventually moving higher. That has played out again this time (four out of four); not only has QE stopped (no more increase of balance sheet), but QT has begun (decrease of balance sheet via non-reinvestment at maturity). $1 trillion later (reduced bond holdings), I believe we are seeing the impact at the long end of the curve

- Certainly, the surprise addition to the budget deficit is a factor. Markets price in what they know of treasury issuance needs to finance deficits; this is not about the deficit but the surprise increase in such.

- The U.S. didn’t go into a recession as so many predicted. Bond yields collapse in a recession. Bond yields were held lower by the expectation of a recession. The lack of one pushed yields higher. If recessionary expectations change, so will bond yields.

- Japan’s Yield Curve Control changes (marginally) put upward pressure on global bond yields

- Declining Chinese exports means China is recycling fewer dollars into Treasuries

- At the risk of confusing or boring you to death, the “basis trade” is very likely a factor – a short position in the futures market combined with a long position in the cash market (financed with repo borrowing). Repo activity is declining, which means the basis trade is unwinding, likely putting upward pressure on yields (for a brief time).

And what we have playing out in stocks right now is certainly a by-product of what is playing out in bonds. But there is more to say than just the empirical observation of high correlation between stocks and bonds.

There’s the rate, then there’s the rate

The federal funds rate is currently set to a target of 5.25%-5.50% (they generally set the target in a range of 25 basis points). They have paused the last couple FOMC meetings, with the futures market presently implying a 73% chance of another “pause” (no move) at the November meeting and a 58% chance now of the same in December. The fed funds rate is the major policy rate in our country, and a million economic inputs and borrowing costs are directly or indirectly derived from it.

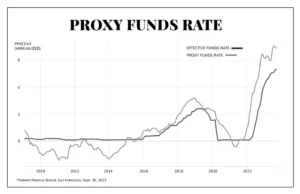

But market activities, other borrowing rates, and the wide variety of complex monetary conditions in our economy cannot coordinate the intentions of the fed funds rate perfectly. This occasional “disconnect” from the target of the fed funds rate and the reality of monetary policy intentions is measured in what we call the “proxy funds rate.” The Fed’s own words are that the proxy funds rate was created to “use public and private borrowing rates and spreads to infer the broader stance of monetary policy.” It uses twelve variables, from treasury rates to mortgage rates to credit spreads, to measure the real or “effective” policy rate in the economy (simply and descriptively titled the “proxy rate”).

Well, it is currently 7%, basically 150 basis points above the Fed Funds rate.

*Federal Reserve Board, San Francisco, Sept. 30, 2023

What does this mean? It means market conditions have tightened more than the Fed has, and that if the Fed did nothing, 150 basis points (six more rate hikes) already have been effectuated in the economy.

This is both the issue and it is the issue (that grammatical device is getting old). On one hand, the market is absorbing very tight monetary conditions, even tighter than the ones the Fed has imposed. But on the other hand, this holds the Fed in check (or at least rational people believe it should, and most prediction markets assume it will).

A 7% rate should be killing us though?

For reasons I have explained previously, the primary (but not exclusive) impact of the current hyper-tightening landscape has been more about inactivity than outright defaults, The cost of capital has kept new transactions from happening, and nowhere is that more evident than residential real estate. But businesses have mostly been able to absorb the increase of funding costs, and many businesses had rates locked out for another year or two. The “maturity wall” of significant corporate and personal debt in 2024 and 2025 is a very different story.

So, you face two issues in the current environment:

(1) The lack of activity (especially in commercial real estate new development) that the current monetary conditions are creating

(2) The forward-looking default risk and credit impairment that we face if the current monetary conditions persist

So if the train is coming, shouldn’t we move?

As a general rule, and I will try to say this slowly and clearly, I do recommend moving out of the way of a blazing train. But of course, that presupposes that one knows a train is coming and doesn’t have a million reasons and precedents for believing the train will stop, go a different direction, take a different route, pick up new passengers, and generally not ask you to get on and give you a first-class cabin.

This is the problem. The train coming at you one second could very well take you to a nice destination instead of running over you another minute.

All things being equal, I prefer not to formulate investment policy around the potential activities of a wild runaway train. In fact, I think dividend growth allows for a reasonable (but not perfect) agnosticism about things like bond yields and runaway trains. But even in the distorted and unpredictable world of interventionist central banks we live in, I can’t say with a straight face that I think the odds are better that the monetary regime rips creditors faces off in 2024 and forces a severe recession than some polar opposite set of circumstances.

This is the dilemma of the Fed put I discussed last week. You know what history teaches you. You know what permabears tell you. You know what the headlines say now. And you are supposed to predict the future around you with such distorted vision?

Oil prices for what they are

I think portfolio managers like me, who are long energy and bullish on the economics of a midstream and upstream U.S. energy story that many other investors have abandoned for non-financial reasons, have a tendency to see oil too much as an investment indicator at times and forget the broad significance it has as an economic input (if this sentence is a run-on, I don’t care; if it isn’t, I knew it wasn’t). The thing that history is unbelievably clear about is that: (a) All the short-term movements and gyrations up and down that really drive trading markets are completely irrelevant; (b) A sustained move in oil prices (up or down) has profound impact in an economy.

More or less, I am convinced that nearly every inflationary indicator has been going south for about a year now and that there will be continued disinflationary moves (albeit at a slower pace) for quite some time. But oil is the fly in the ointment.

Should oil hold below $75, it presents huge bullish scenarios. Should oil hold below $60, it likely means there has been significant demand erosion, and things are breaking. Should oil hold above $90, it eventually (again, the keyword is “hold”) puts downward pressure on the dollar and becomes inflationary. Should oil hold above $100, it eventually becomes very erosive of demand and does real damage in other parts of the economy.

We have not encountered a period like this in some time. Demand has stayed very high. There is a war going on. There is an OPEC+ who is tired of the marginal buyer of oil settling the accounts with the marginal producer in a currency they control. There is the leading economic superpower of the world that refuses to be the marginal producer even though it easily could be dealing with cultural forces asking it to surrender its leverage.

I don’t know how stock or bond markets, let alone twelve men and women in a conference room, could price in what to expect from this dynamic. It is a surreal and unpredictable set of circumstances. My very sincere advice – own in your equity portfolio both things that benefit from higher oil prices and things that benefit from lower oil prices.

Conclusion

Decades of fiscal and monetary insanity have not, contrary to popular belief, created an apocalypse. They have created a wildly unpredictable set of conditions that are not going away in your lifetime or mine. The current conditions are not apocalyptic – they are “par for the course” stock market volatility – not even close to above average. Yet bad policies create more bad policies, generally speaking, and in the meantime, one decision in monetary intervention usually leads to another intervention. And these interventions create zigs and zags that become very unpredictable and also create moments (a month, sometimes less, sometimes more?) of “re-pricing.” Utilities have gotten hit this month. Commercial real estate cannot get funded right now. Bonds are down, but new bonds look really, really juicy. Tech valuations are still very, very high, but they could go higher from here, or they could go way lower. The Fed may pause. The Fed could even hike (I really doubt it). And they most certainly could end up cutting (and will, at some point).

Your portfolio and financial well-being depend on not believing you know how it will all shake out. But also, you owe it to yourself to understand that they don’t know either (the Fed, Congress, expert hedge funds, MIT economists, etc.). And you owe it to yourself to understand that the factors we have discussed today are known by markets and reflect some of the risk premiums priced in.

The good news is, with discounting mechanisms like markets, trains everyone knows about generally do not run over you.

The bad news is there are always trains no one sees.

Dividend growth is your ticket to the optimal destination

Chart of the Week

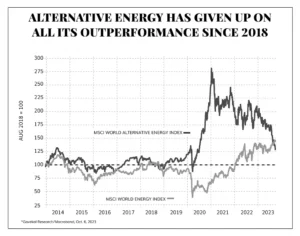

We can talk about the crypto bubble burst, the shiny objects of SPACs and IPOs, the “unicorns” of the last decade, and all the other froth and speculative insanity laid to rest on the ash heap of history. But the implosion of the alternative energy bubble has to be part of that same conversation, apparently.

Quote of the Week

“What does it take to be a great President? It’s easy. You come in after Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter.”

~ Ronald Reagan

* * *

Back to New York City this weekend and ready for our annual due diligence meeting with over a money managers and hedge funds the week after this coming week! Lots and lots happening right now, and earnings season kicks off in a few days. Markets never sleep, but Trojans do fight on.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet