Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Before I get into this week’s wild fun Dividend Cafe on the subject of government debt, I want to make sure I do one final push around the [annual] Year Ahead, Year Behind White Paper that we published last Monday. Because of its depth and length, I imagine some of you printed the chart-filled PDF and plan to digest it this weekend. So don’t worry – if today’s Dividend Cafe is coming on top of your white paper reading, I assure you the data I cover this week about our fiscal position in America will not be going stale in the days ahead! If, for some reason, you missed Monday’s delivery of the Year Ahead, Year Behind edition, the paper is here, the video is here, and the podcast is here.

But now we re-dive into the standard Friday routine of our weekly Dividend Cafe. And this week’s is a very cheery one if you are cheered up by massive government spending and debt (hey, “we’re all Keynesians now,” right?). A fundamental component of our macroeconomic view going out ten years and longer is a belief in an internal tension in the American economy – that is, the extraordinary engine of growth and innovation that the greatest Western democracy the world has ever seen is and has been for 250 years, VERSUS the significant headwinds for growth created by excessive government indebtedness. The story is more nuanced than that, and I will get into those nuances and more in this week’s Dividend Cafe.

Don’t think of this week’s Dividend Cafe as a position paper on how to solve for the national debt. It is not a policy paper but rather a reaffirmation presentation of the state of affairs. Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe!

|

Subscribe on |

Did someone say nuance?

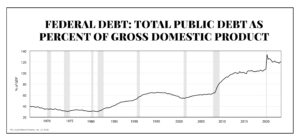

I am going to use this week’s Dividend Cafe to present the empirical facts about federal government indebtedness in our country as well as provide some data that speaks to the challenges of taxing our way out of it. But I want to be clear about something I have asserted for years: The dollar amount of debt is not my concern; it is the debt as a percentage of the size of the economy.

At the end of the day, this should be very obvious. Billy Basement Boy has $9,000 of credit card debt, and Apple has $111 billion of debt. Who do you think is in a stronger fiscal position – a kid without a consistent paycheck in a garage playing video games, paying for his DoorDash and “pharmaceuticals” on a credit card, or the most profitable business with the most cash assets in history? The DEBT is best understood in the context of its relationship to income, to assets, and ultimately, to productive capacity.

And that leads me to the second nuance. I care about this debt-to-something ratio because I believe it limits future growth and opportunity. Period. It is not armchair stuff. It is not political. It is not academic. It matters because it impacts something real.

I was vocal about the spending that took place from 2000-2009 in our country. No matter what anyone believes about the wars in Afghanistan, the Bush tax cuts, the No Child Left Behind spending bill, the prescription drug (Medicare Part D) bill, etc., while deficits went higher and national debt expanded, the ratio of that debt to the size of the economy didn’t move much. That all changed in the financial crisis (as seen in this chart).

This gave way to a tea party movement and a fiscal fight between the White House and the Congress in 2011 that gave us a sequester and a few other cute little interruptions to things, but at the end of the day, post-crisis life in America has been one of expanded debt, expanded deficits, and most importantly, an expanded percentage of debt relative to our national output. And this has led to a declining growth of output. Rinse and repeat.

Bipartisan

I shouldn’t stop my analysis at the post-crisis moment of debt-to-GDP expansion. That could give readers the impression that I am blaming this on the period of time that President Obama happened to be President. My own view is that there have been four Presidents in a row who have overseen a huge expansion of governmental spending relative to economic output – two of those where Republican and two Democrat. This is not a partisan criticism. Objectively, how could it be? And in fact, I will add that in the post-Obama years (see the chart above again), the debt increased significantly, even before the COVID moment explosion. I have had plenty to say about this from Bush to Obama to Trump to Biden. Just sayin’ …

That isn’t a mere virtue-signaling comment about political objectivity, though. It is an important part of the fact pattern here. Embedded in the economic prognosis is a view (supported by the testimony of history) that each side seems to be only concerned about expanding spending and debt when the other side is in charge of the White House. If there was some bipartisan consensus – a mutual agreement about addressing it (even if there was understandably stark contrast in how each side wanted to address it) – that would be a different story. But I am convinced that the politics of this are irresolvable. Debt, deficits, and spending only matter when the other side occupies the White House.

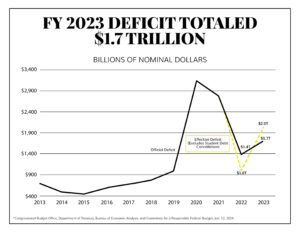

We are not to the point of solving when we are still at the point of rapidly making it worse

The most sobering thing about our state of affairs is beyond, well, the state of affairs. It is that we do not have a bad problem with no clear path to fixing it – it is that we have a bad problem that we are making much, much worse, quickly.

A family with $100,000 of credit card debt that can only afford to pay $2,000 a month on the debt has a big problem – they face a real challenge to their quality of life for many years while they try to pay that down. However, a family still adding $2,000 of debt each month to their credit card debt is in an entirely different category of problem.

Where are we as a country?

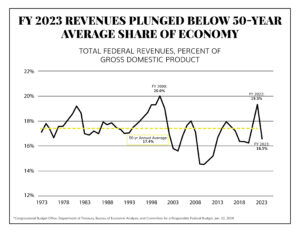

The solution that isn’t

So you say we need more revenue. Simple enough. How is that going? With higher tax dollar receipts than ever, the share of tax revenues to the economy is shrinking, even as the share of spending to the economy is exploding.

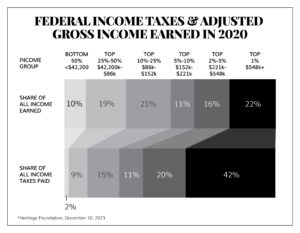

No problem, you say. Raise taxes on the rich! The top 1% of America’s income earners earn 22% of all income earned and pay 42% of all taxes paid. In other words, if they earned 22% of income and paid 22% of taxes paid, it would be tough to say they aren’t paying their fair share. But the highly progressive nature of our tax code means that it is actually exponentially true the other way. Now, some may feel this is unfair, and some may feel it is a good thing – my point here is not to get into the ethical propriety of a progressive tax code.

My point is pragmatic to the point of governmental fundraising: You don’t actually have a lot to gain by asking 1% of people paying 42% of taxes to pay more. The segment below earning a much higher share of income than the share of taxes they are paying is 85k-150k and 42k-85k segments (textbook middle class). Good luck with the politics of that!

A little more piling on

Social Security and Medicare’s unfunded liabilities are not really even addressed here. As it stands now, the outlays for these various transfer payments in our safety net are the largest part of government spending. But it isn’t going to merely stay “as it stands now.” It has to get worse, or payments get missed. I do not predict that payments will be missed. I predict something else. But my prediction should not be thought of as the “half-full” vs. “half-empty” side of things – I think my prediction is worse. I think they will deliver promised social security checks, and it will come at the cost of greater fiscal indebtedness. That would put us near 180% debt-to-GDP (to fully fund social security obligations) – not the 108% we live with now (108% is debt held by the public and excludes inter-governmental debt).

So what are you saying?

It’s best to make clear, first, what I am not saying. I am not giving a doom and gloom prophecy, and there are two reasons:

- There are objective and more substantive things to say that paint a more complex picture than paperback apocalypse (more on that after point #2);

- The doom-and-gloomers are always, always, always wrong. Like embarrassingly wrong. Pitifully wrong. Totally lacking any self-awareness wrong.

So, no, I won’t attach myself to the chicken little worldview.

The other reason I am not talking “doom and gloom” is that I believe Japanification is a more realistic consequence than a sudden “end of the world” moment. The whimper and not the bang is still, well, not good. Yet the “Japanification” message of low/slow/no growth over long periods of time as a consequence of debt, with intermittent periods of crisis that all of a sudden force action, is to me a more realistic scenario than those predicting the end of the world (for the fiftieth time).

The risks we face in this excessive indebtedness can be summarized in the category of “suppressed economic vibrancy,” – but that itself requires an explanation. Why should you care about “suppressed economic vibrancy” if you have a job and some money in the bank? Because:

- It makes the financial system more fragile so that when bad moments come, they are worse than they otherwise would be

- It means less growth and productivity, which means fewer jobs, wages, and profits in the future if you care about that kind of thing (kids, grandkids, posterity)

- It means cuts in some parts of government we may need (military) to fund the parts we have committed to but not funded (transfer payments)

- Declining economic strength and leverage hurts our geopolitical advantages with potential enemy states (China, Russia, Iran, Saudi, North Korea, etc.)

- It incentivizes policymakers to combat a bad situation with a worse one! It fosters more intervention, distortion, and instability.

All of that “suppressed economic vitality” is demonstrated over time in a suppressed quality of life, both in opportunity cost and absolute standards.

The reality is that I am reasonably optimistic about pockets of cyclical growth opportunity (a new capex cycle is one big example) in the midst of the larger structural debt challenge. This debt challenge is not likely to be met by 330 million Americans getting on the same page or politicians saying and doing hard things. Investors must prepare accordingly with thoughtful, fundamental, rational, and disciplined solutions.

To that end, we work.

Quote of the Week

“The whale is never harpooned until it spouts.”

~ Edward Thorp

* * *

I am optimistic for a guy living in a 108% public debt-to-GDP country. I am optimistic about my Cowboys chances in this week’s playoff game, too, though, so what does that tell you?

Do enjoy your extended weekend, and we look forward to a special DC Today on Tuesday the 16th!

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet