Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

As we proceed through the one-year anniversary of the end of Credit Suisse (globally) as well as Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and soon First Republic (domestically), it is worth stating that not a lot has gone the way anyone predicted a year ago. Permabears and conventional economists alike did not get their universally-anticipated recession. The Fed did not capitulate by quickly lowering rates. The Fed also did not go to Volcker-like 6, 7, or 8-handle interest rates. Unemployment did not surge to 5%. Inflation did not persist at surreal levels. Corporate profits did not drop. Oil production has not slowed. Electric vehicles have not taken off. Regional banks have not failed en masse. The GOP did not nominate Ron DeSantis. President Biden has not been replaced as a candidate by Michelle Obama. Travis Kelce did not propose to Taylor Swift at the Super Bowl. And perhaps most tragically, USC did not have a good 2023 season (but alas, we fight on).

Predictions are fun. They are not, though, at the heart of the investment business. They can be very important in the methodology and process of some speculators, and they can even be marginally additive for some investors. But “predictions” are not quite the same as “calculations,” and they are categorically different from “belief systems.” At the core of all good investors lies a philosophy. I find it an unimprovable joy in life to study the investing philosophies of great investors. I never, ever, ever find one who relies on “feel” or “just has that Midas touch.” That very thinking is for simpletons and know-nothings. Great investors execute well off of a cogent philosophy. Bad investors either fail to execute or have an improperly formed philosophy (or, worst of all, options; they have no discernable philosophy at all).

The Bahnsen Group embraces being defined by our investment philosophy, and we embrace being known by the role dividend growth plays within that philosophy. Dividend growth is not new. In fact, what is [relatively] new is NOT viewing the receipt of cash flow from the risk investments you make as a key objective in your investing and a significant part of your anticipated return. In today’s Dividend Cafe, we address the history of investor distraction from dividend monetization and the reorientation that we believe is about to shift the focus back to where it belongs. We are not talking a “new normal” but rather a “return to normal normal.”

So jump on into a very normal Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

History trumps Business

I have long been fond of Daniel Peris, a dividend equity manager at the Federated Funds who has a doctorate in modern Russian history. On one hand, I realize some may have a hard time connecting the dots, but on the other hand, I cannot imagine and less-equipped person to professionally manage money than one who has no grasp of history. The specifics of the Soviet empire may not directly correlate to fundamental equity analysis, but I absolutely believe the capacity for understanding history – the training that evaluates history analytically and carefully – is directly advantageous in both the art and science of portfolio management. Peris has a new book looking at the historical and cultural artifacts surrounding changes in investor demand for cash flow, and what it teaches us is profoundly important.

In the Beginning

The history of dividends as paramount evidence of the success of a public company is thorough and exhaustive. It may strike some readers as kind of boring, but it isn’t vague or incomplete. For a longer period of time than you would believe, dividends were assumed to be the value of public company investment or at least a vital consideration within the total value proposition (to investors). The listings of public companies often showed a par value with a dividend yield, the latter being the instrument that reflected profitability and value (not the boring par value). If a company did not pay a dividend, the assumption was that it was in distress. This was “par for the course” for centuries (see what I did there).

And I should add there was way more capital intensity through most of the 20th century than there is now (that is, companies were paying dividends because investors demanded them, despite the fact that companies needed to reinvest far more of their capital (including self-created capital via profits) into the ongoing operations of the business. Industrials, Manufacturing, Utilities, and so forth were profitable activities, but they were capital-intensive. Dividends were a prominent reward for investors in a period of higher capital intensity. We seem to have moved the other way. Investors have been less demanding of demands despite the companies needing much less of their self-created capital for reinvestment? What is going on here?

A blast from the past (of one week ago)

I wrote last week about the underlying issue of relevance when it comes to dividend payments (versus those who errantly claim a dividend staying in the company coffers is the same thing). The fungibility argument suggests (prima facie) that it is irrelevant to an investor if they receive the dividend or a company holds on to it, but that argument dies upon further analysis (to put it mildly).

Money is not fungible from the vantage point of business ownership. The minority owner of a business with no operational control does not have a “potato-potahto” luxury when it comes to the return of capital. As Peris puts it, “the natural mechanism for sharing in the success of the enterprise” is the dividend.

I love the analogy he gives. 2+2=4. And also (18*235)*(2^2)/((SQRT(400))*15)-((3^3)*2)-20 also equals four. Does everyone agree they do not exactly get there the same way?

The dividend is a check in the mail, and once sent and received, the risk is gone (for THAT portion of monetization). Attempting to hold on to unrealized capital gains (or realize them) MIGHT get to the same place, but in each case, multiple new risks become a part of the process each step of the way. Unrealized gains do go away. Using companies that have gone up in price and not down to compare to dividend ownership is survivorship bias. What about dividends received from companies that struggle later? Harvested capital gains will be lost; dividends substantially mitigate that loss. 2+2 really does equal four.

(I should point out that if companies that gave up 70-99% of their unrealized gains in recent years, like Peloton and Beyond Meat and Zoom and Lyft – I could go on and on had been paying dividends it is not just that the losses would be less; they wouldn’t be down 70-99% because it would have meant they had actual profits to pay out). But I digress.

Resistance

Peris’s book showed that a paradigm of not understanding dividends or their superior role in practical investment strategy did not necessarily begin in the cool era of the tech 90s – that there were various academicians attempting to throw shade on dividends in the 1970s, as well. Tax regimes were once a culprit. Investor naivete made its way into the literature. And through it all, dividend growth kept chugging along, confounding the critics who were simply unable to grasp one of the most basic of concepts – the tangibility of the received dividend.

The modern era

The number of companies paying a dividend within the public market indices did begin to drop in the 1990s, as did the payout ratio from the companies who did pay (i.e., the portion of earnings paid out in dividends). This, over time, reduced the investible universe for dividend growth investors like us but also placed a premium on the value of the well-behaved companies that stayed faithful to their investors. Peris posits a few explanations for the changing paradigm within the broad market about dividends:

(1) What perhaps belongs at the top of the list is the secular decline in bond yields that began in 1981 or so in earnest. Companies that previously competed with a federal government that was paying 10-15% to investors in the bond market began competing with 9%, then 7%, then 5%, then 3%, then 1%. The “reference rate” that investors had as a basic benchmark for income went lower and lower and lower, which enabled companies competing for capital to follow suit. This is top of my list in explanation.

(2) And, of course, stock buybacks became another way for companies to return cash to shareholders (SEC rule 10b-18 passed in 1982). Peris addresses the issue in his new book, and I addressed it in my book, as well, but this vehicle became a bonanza for corporate managers who were paid off of earnings per share so much that they reduced the denominator of shares in the earnings-per-share formula. Low rates incentivized companies to borrow money (debt, making the company less valuable) to buy stock (making the shares more valuable), all without doing anything – nothing -zilch – nada – to the operational, strategic, organic, competitive reality of the business. So stock buybacks, when used properly, became a competitive (and popular) alternative to dividends in terms of capital return but came with numerous qualifiers (or outright downside) that were frequently ignored in the positive trendline of the great bull market.

(3) The general social and cultural reality of Silicon Valley should not be ignored, either. The last decade of the last century saw an explosion of technological growth fueled by the innovative use of silicon technology that generated extraordinary growth. The R&D and growth culture of the Nasdaq world was not dividend-centric, and this became increasingly embedded over time (to the detriment of investors, as full CAGRs over multiple decades make clear). Money-losing enterprises are common in the Nasdaq, and money-losing enterprises do not pay dividends. Investors became more tolerant of money-losing enterprises (think about that sentence) than they historically had been because of the promises of great riches on the other side of the scale. In isolated cases, the growth focus of certain tech companies paid handsomely well. In many cases, it set money on fire en masse. For investors, there was (and is) a casino-like culture to it, but it served as a substitute for the dividend-based fundamentals of minority ownership in public companies for quite some time.

Where are we now

Bond yields are still much lower than they were in 1981, even though they are higher than they were in the post-GFC period of zero-bound. Stock buybacks are still prevalent but increasingly demonized by the left (and now many on the “right”).

Additional taxation is threatened constantly as stock buybacks become the bogeyman for class warfare.

And the hipness of Silicon Valley deals with booms and busts that, all at once, reward casino players who time their exits well and devastate those who don’t. Where unrealized capital gains do accumulate they face the issue of monetization, risk compounding, and misalignment with management and shareholders. And the Nasdaq, no longer a new shiny object, has a multi-decade track record of booms and busts that are clear for asset allocators who have, well, studied history.

Cash-based investing will never wipe out speculation-based investing entirely because cash-based investing cannot defeat human nature. But the failed investor that is human nature can be tempered by a few things, behavioral modification being one of them. And I can think of no modification to behavior more efficacious than to rely on consistent and growing cash payments from one’s investment to drive one’s investment plan. A gazillion investors are entering an extended period of needing cash. The long-term arc of history and, more importantly, cogent financial philosophy dictate the same thing: Dividends are the reward minority owners in public companies want, deserve, and need.

To that end, we work.

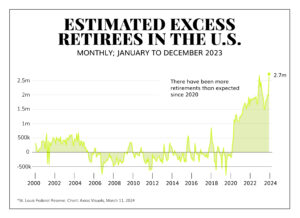

Chart of the Week

Does this chart tie into the subject of today’s Dividend Cafe? You tell me.

Quote of the Week

“The beauty of investing is you don’t have to make money back the same way you lost it.”

~ Bill Ackman

* * *

I will leave it there for the week. I love this topic. I love this endeavor. I loved Daniel Peris’s new book. And I love managing a dividend growth portfolio for the betterment of our client’s lives. And yes, I love March Madness. But I will say speculating in my bracket did not seem to work well so far. I wish there was a way to find solid dividend payers in that!

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet