Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Dividend growth investing is counter-cultural. It goes against the grain of “hot dots” and “shiny objects.” It functions outside the fads and fashions of the moment. And it insists that ancient ideas like “cash flow matters” are still relevant today (amongst many other ideas). It seeks performance and productivity but not popularity. It flows from a belief system and not a crowd. It is, indeed, counter-cultural.

It also is not always understood correctly. Several misnomers persist that, if better understood, could jeopardize its counter-cultural status. One of my great fears in life is that dividend growth investing recaptures its status as “the known way to do equity investing.” All things being equal, if dividend growth investing became a consensus understanding of the masses, I still wouldn’t change my belief system one iota, but I prefer running a portfolio at 15.2x forward earnings when the market is trading at 21x … the “non-shininess” of the strategy adds value.

Nevertheless, when it comes to the Dividend Cafe, it is my sworn duty to inform, educate, equip, and edify, so clearing up misnomers is not just allowed but required. If enough people read and adopt the truth, I may have to sacrifice the counter-cultural status of dividend growth, but I’ll know I did the world some good. So today, we shall clear up a couple of things and even dig into some recent history.

And as is always the case with financial markets, the more you understand the past, the better prepared you will be for the future! Jump on into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

What does it profit a man

I have written before about the heart of the matter when it comes to company policies around returning capital to shareholders. The underlying truth that can’t ever be forgotten for dividend growth investors is that all we are talking about is what a company does with after-tax profits. The dividend is a post-profit activity – in other words, the dividend payment presupposes there are profits to pay out. A company has to do something with profits.

One thing they could do is, well, not have any. And, of course, companies with no profits can still see their stock prices go up (heck, for some, it is a badge of honor). And many VC-funded companies plan not to have profits for a period of time because they are ramping up for the future. At some point, on this side of bizarro land where 2+2=4 and E=MC squared and all that jazz, a company’s path is still supposed to be towards, wait for it, profitability.

But the investor objectives associated with a dividend growth strategy are generally growth of capital with a certain bandwidth of downside volatility, and/or current income, and/or future income, and/or current and future growth of income. Dividend growth is the strategy we have devoted our lives to around various combinations of those investor objectives, with varying degrees of bandwidth for investor comfort with volatility. It is not in the same category of “venture capital” type investment, which has its place, just for a different goal, outcome, and risk profile.

So what we are talking about here is companies that have profits and what to do with them. It is worth conceding the point that if a company has $10 of value, adds $1 of profit, and holds on to that profit, it is now worth $11 to the investor, and if a company has $10 of value, adds $1 of profit, and gives that $1 profit to the investor, it is now worth $11 to the investor. That is the easy part. But if 10+1 equals 11, whether the company has the extra $1 or the investor does, what is the fuss about when it comes to dividend growth?

Why it matters

The basic assumption that a dividend returned and a dividend retained is the same thing (in terms of theoretical value) is not the underlying issue. Profits are profits, and cash flow is cash flow – we have that part down. The fundamental issues are:

- What we know about the types of companies able to pay (and GROW) a dividend year-over-year, AND

- What we know about the INVESTOR mechanics needed to monetize an investment, AND

- What we know about the MATH of investor returns (and volatility) when a dividend makes up a higher share of it

Profits may be profits, whether retained or distributed, but the problem for investors is that profits don’t help investors (who need them) when they own public companies because they don’t get them unless paid managers say so or if they sell shares. One can say, “I will just sell shares to receive my profit,” but it should be rather obvious that they become exposed to timing risk and negative compounding – and I would say, profoundly so. And since stocks can go down for 2-3 years at a time (2000-2002, 1973-1974, and has had a plethora of negative years), and since stocks experience drawdowns that annually average down -14% in the middle of even positive market years, and since stocks are down almost as often as they are up on any given day, and since stocks trade not purely around profits but rather sentiment … the “I can sell a share” versus “I got paid the dividend” are just not even remotely comparable. It is an intellectually indefensible argument.

The dividend smooths the profits for the investor, provides mechanical automation of risk monetization in a way that is always positive and assures that they will never negatively compound. When roughly half of the return comes from something that is ALWAYS positive, vs. 95% of the return coming from something that goes anywhere from -25% to +25%, the VOLATILITY of the return is categorically different. Add in the fact that companies that manage their business to annual dividend growth have better balance sheets, better debt profiles, better M&A discipline, and more aligned management. This idea that the mechanics of returning profits to shareholders do not matter is absurd.

Arrogance in the C Suite

There are companies that will say, “Why would we give our shareholders their money back? We can do better with the money than they can!” This isn’t just arrogant, it is incoherent.

First of all, any investor who needs income (i.e., cash flow) from the investment has to be removed from such consideration. What the return will be with the capital (retained earnings) in question is immaterial if one needs it for groceries, living expenses, boat payments, taxes, college tuition, USC football tickets, Chinese food, or annual foundation grants. “You can’t eat retained earnings” is an expression I just made up right now, but it works (I stole it from “you can’t eat IRRs,” which is also demonstrably true – internal rates of return in private investments do not easily translate to groceries).

Secondly, if it comes down to the return of the company in question, the dividend the company pays can be, and very often is, reinvested in the underlying company. In other words, if what one means is that the return of the company’s stock price will be so good that paying out a cash dividend decreases the investor’s access to that return, then it is just patently false. The vast majority of accumulators of capital reinvest their dividends in the company paying the dividends. It is akin to apartment owners who use rent checks to buy more apartment units, and it is textbook mathematical compounding.

No one is talking about the return of the stock with the portion of profits paid (or not paid) as dividends. If you need cash flow (as all investors do eventually), it is immaterial who will do more with the cash in question, and if you want to accumulate more of the profits of the underlying business in question, you can absolutely do so via share reinvestment.

The issue is WHAT TO DO WITH the fruits of the strong returns. If an investor wants to reinvest their dividends in more shares of the tree bearing the fruit, they can (and should) do that. But there has to be fruit from the tree. This becomes an issue only if the COMPANY NEEDS THE FRUIT to keep generating more fruit. Exxon can’t pay out 100% in dividends because to generate ANY dividends, they need a CONSTANT amount of NEW CAPEX. Many companies have very low capex needs. Yes, SOME profits must be reinvested into the company, and a company should be growing equity via the fortification of its balance sheet. But when a company is generating profits, they do not generate MORE of such by NOT distributing their profits unless they have opportunities they are NOT investing in that are outside what they do to generate profits, to begin with (i.e., their core competency). THAT is where companies go astray,

C is for Conflict

There is no precedent in human history of a company compounding on the very capital generated from earnings at an escalating rate forever. The incentives are terrible for a C-suite to be in competition with shareholders in a scenario like this. Bad deals get done, and money gets set on fire. The C-suite stays humble by dividend payments – they do not become god-like in the amount of retained earnings they are expected to reinvest at an equal or greater return than that which created the return you begin with.

Risk compounds over time. Periodic dividends de-risk the investment. And, return opportunities diminish marginally over time. Corporate executives who do not know this are the embodiment of arrogance. Stewards of shareholder capital know it and hold in tension their perpetual fiduciary duty to monetize shareholders while retaining enough capital to grow the business.

Performance trade-off myth

The empirical reality is that dividend growth does perform better for investors than broad index ownership (for decades at a time). Academic studies pontificating whether this should or should not be true miss the point that it is true.

A more recent thesis I routinely see is that dividend growth does outperform the index (and especially so during bad or flat markets), BUT that it isn’t because of dividends, but rather because of other factors (“value” and other considerations). Trying to debate the cause of why something did better is odd when the thesis was supposed to be that it doesn’t do better. Like someone arrested who says, “I didn’t do it, and also, I had a good excuse why I did,” I think there are some shortcomings here. =)

Recap

There are a plethora of reasons why investors do not want companies to retain all earnings they generate from their underlying productive business activity:

- Profits are needed for other purposes than reinvestment (i.e., cash flow needs of the investor).

- Dividend reinvestment gives the investor the ability to maintain the same value position in the company and even build an internal compounding machine around the flow and reinvestment of dividends.

- Risk mitigation.

- The testimony of history.

- Something has to be done with capital—the question is, what? If the answer is to “perpetually have the company re-allocate,” I have to know what these companies are that have a never-ending, infinite need for capex and reinvestment opportunities never subject to the law of marginal utility.

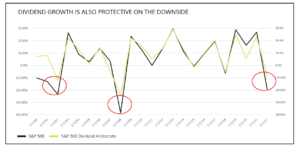

Chart of the Week

I am sure I have shared this chart before, but it warrants sharing again. The mechanical, philosophical, mathematical, logistical, operational, and financial benefits of dividend growth notwithstanding, the downside protection in severe market distress is noteworthy, too. Even using passive dividend indices (which are themselves sub-optimal, as our own experience makes clear), the improved downside buffer caused by the dividend payment itself, the superior balance sheets, and more defensive business models is inescapable.

*FactSet, December 2023

Quote of the Week

“The market may be crazy, but that doesn’t make you a psychiatrist.”

~ Meir Statman

* * *

I thought I would spend some time this week talking about the reasons dividend growth became more counter-cultural this week, but other themes took all the time and attention. Next week I will delve into this a bit more. Dr. Daniel Peris, a dividend growth portfolio manager, and friend, has a new book out on this very subject, and I want to break out some of his findings, both in the lay of the land of the last forty years and expectations for the next forty. His podcast comments here were intriguing, and I think the overall subject warrants more discussion in the Dividend Cafe.

So in the meantime, get your brackets ready, prepare for the Madness of March, and stay focused on the dividends of what is real and tangible. To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet