Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

The first thing I will say is that by popular demand, we will be adding back the “What’s on David’s Mind” to the Tuesday/Wednesday/Thursday email blasts starting next week for Dividend Cafe subscribers (and on some days, “What’s on Brian’s Mind”). By and large, the feedback to the newly revamped Dividend Cafe has been overwhelmingly positive, and a few knobs turned on the daily programming will continue to fine-tune. Thank you all for your feedback; we are very excited to have one property, one brand, and one medium to deliver the TBG thought leadership to you.

This week we are going to look at the history of yields from the market today, the history of market drawdowns, the state of commodities, the future of national debt, some global debt to avoid, expectations for Chinese economic growth, the energy sector, and finally, some Presidential conspiracy theories. That’s a lot to pack into one Friday. No one said this would be easy; we only said it would be fun.

Let’s jump in to the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

Telling the truth on capital return to investors

The dividend yield on the S&P 500 in the 1940s, the 1950s, the 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s was around 4-5% (with a little vacillation up and down around that range). The yield today is 1.25%. Many have tried to explain that away by saying stock buybacks were legalized in the early 1980s, and if you add that to the dividend yield, you get something similar to the historical average of dividend yield (a so-called “dividend + buyback” yield).

First – this is not true, even if it were true, because you can’t eat buybacks, you don’t have anything new in your checking account, and the buybacks do not account for new share issuance created on the other side of the pool. Buybacks are not dividends, no matter how hard people bastardize math and the English language to say otherwise.

Second – it also just isn’t true. WITH buybacks added in to dividends, the combined yield is currently 3.1%, almost two percentage points below the dividend yield average of the market for the fifty years prior to buybacks becoming a thing.

Figures sometimes lie, and liars often figure.

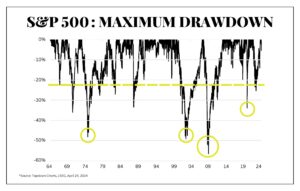

Drawing the drawdown

As of Friday, April 20, the S&P 500 was down -5.5% from its March close, which was then its all-time high. The S&P was up over +2% this week (as of early trading Friday morning) so that drawdown is already vastly reduced. The index is still up +7% on the year and still above its 2021 closing high (which it was not above enter 2024 even after the huge rally in Mag7 that drove 2023’s strong returns).

But lest we forget, -5% drawdowns don’t even get to half of the normal, year-by-year standard par for the course intra-year drawdown. Look, the COVID, GFC, dotcom, and 1970’s REAL market fiascos are circled below, and there are plenty of “corrections” and “bear markets” that go -10% to -25% besides those doozies. But the -5% to -10% drawdowns are really an annual affair.

Commodity Consistency

One thing that is consistently true of commodity prices – people who trade commodities or are otherwise engaged in a long approach to commodities are always certain that “a new rally era in commodities are upon us.” The reason and rationale will sometimes change, but the consistency of optimism around commodity prices that commodity buyers have is a sight to behold.

Of course, this does not mean they are always wrong. The decade of the 2000s was a golden era for commodity investors (along with emerging markets investors, dollar bears, value investors, and more). 2011-2020 was a pretty slow but non-stop reversal in commodities, moving down and to the right throughout the decade. A surge in prices took place in the COVID re-opening and subsequent inflationary period, and prices have essentially come down ever since that supply/demand imbalance surge that took place in 2021. Well, now, there are a lot of commodity bulls screaming, “This is it – we’re back!” and I do not disagree that better-than-expected U.S. growth (for now), geopolitical volatility, and the possibility of a dollar eventually softening and emerging markets getting their due would help the long-commodity devotees.

But as long as there are operating businesses in the world, there are better ways to get exposure to these times than investing in the raw materials of the world. What we do with raw materials is more profitable than speculating on the prices of the materials themselves. Consider this a creational normative.

A Debt-to-GDP Question for the Ages

I am frequently asked if I believe the government will default on all the debt they have accumulated (a debt that is growing year by year as spending has exceeded tax receipts every year for nearly 25 straight years) OR if I believe it will solve for the debt-to-GDP crisis by raising taxes? The presupposition in the question is that one of those two options is the only two options. It is not so.

There are many alternatives to default, and we could go through those any time you’d like. None of them are great, but imagination is important here. But on the flip side, I am never quite sure why people believe raising taxes would solve the debt-to-GDP challenge. High tax states have learned the lesson of Laffer’s Curve the hard way, that higher tax rates paradoxically reach a point of lower tax revenue as people move, leave, or otherwise find ways to pay less. But more importantly, you cannot raise taxes at this point without reducing GDP. The ratio would worsen as economic growth would suffer behind the movement of money from productive use to non-productive use. And we must remember, tax increases are off the table politically for the middle class (according to both parties).

I do not believe higher taxes will or can be a solution. And I do not believe default is the likely end run. Sadly, I believe the end run is years, if not decades, of anti-growth distortions, central bank monetization (or, more likely, quasi-monetization), and downward pressure on growth that whimpers rather than bangs as long as possible.

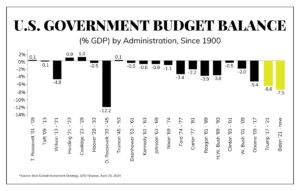

Deficits divided by the economy

Speaking of which … the amount the budget deficit represents as a percentage of the economy (expressed as a negative because, well, never mind) has – shall we say – picked up in recent years. Hopefully, you can look at this chart and see why I am less excited about this upcoming election than many of my friends on the right and the left are.

Dissing a whole asset class

There was a period of time when we were allocating to emerging markets debt at our firm. Within taxable fixed income and later within our specially designated Credit sleeve, EM debt offered high coupons (in a U.S. zero rate environment), and we felt we were being compensated for the credit risk and currency risk the asset class embedded. Additionally, the secular thesis in our emerging markets equity conviction (reserved for clients seeking Growth Enhancements in their portfolio) seemed consistent with ownership of EM debt (that is, significant structural growth rates in the underlying economies, demographics, the emergence of a middle class, and more). What we eventually decided was that the bond-like returns with equity-like risk of the asset class were a bad pair. A ~5% yield could be obtained in less volatile aspects of the credit spectrum without the volatility that geopolitics, trade dynamics, debt dynamics, and especially currency risk provided. I continue to study the EM debt world because it speaks to monetary theory, forex, and global macroeconomics, but it has been un-investable for many years at TBG.

The Chinese Conundrum

As previously reported, China’s GDP number for Q1 came in at +5.3% y/y, compared to +5.2% in Q4 of 2023. Exports have remained strong, prompted by the economic strength of its trading partners. The property sector continues to weaken, but other offsetting factors have kept growth in place. The challenge Chinese policymakers have is to determine whether or not inviting the collateral damage of more policy interventions is worthwhile if other industrial, trade, and manufacturing metrics are going to hold solid. Attempts to reallocate resources to construction and real estate financing all at once risk not working and may very well be unnecessary if other parts of the economy offset the property sector deterioration anticipated. The one thing we do know – government attempts to prompt one sector over another come at a cost. We are about to find out if Chinese policymakers believe that cost is worthwhile.

Sign of the times

U.S. Energy trades at 70% of Apple’s market cap (like, the entire U.S. energy sector), but is generating free cash flow that is 120% of Apple’s.

Debunking a conspiracy myth

A client reached out this week, shocked that the GDP number for Q1 came in so much lower than expected. “In an election year, isn’t the incumbent trying to boost these kinds of numbers, not see them print lower than people anticipated?” (was the gist of the sentiment). And all things being equal, I think we might be on to something politicians prefer good economic numbers to less good ones when running for re-election (you can fact-check me on that one).

But can I just ask a question, please? What exactly is a President supposed to do to “goose” the numbers in an election year? I mean, I suppose last year he could have sought to pass big tax cuts or deregulation, but I have good sources who tell me that there wasn’t a lot of talk about doing that. There are other more cynical or crass things one can do that may curry favor with particular voting constituents (just spit-balling here, but student debt transfers and strategic oil reserve releases could foot that bill), but those things don’t generate broad economic growth – they are more targeted (and candidly, more ambiguous about their political benefit since they alienate one group while making happy another).

But when it comes to general “GDP optics,” other than more conspiratorial beliefs that they can just flat-out cook the books and get 2,000 government workers to keep their secret (“ssshhhhhh, don’t tell anyone”), there is not a lever a politician can push to just, voila, make economic growth happen. Believing there is comes from two problems that I consider among the most distressing things in modern times:

(1) A messianic view of the Presidency that bestows upon it magical economic powers it does not (and should not) have

(2) A total economic ignorance as to how economic growth happens. The production of goods and services flows from human action – from risk-takers putting capital investment, time, and manpower into activities that generate output. Optimism, confidence, and financial conditions all play in. There also is a cyclicality to it all. But I have almost never met an entrepreneur who said, “I have this great idea, but I am waiting to see who is President.” It can happen, but not often. One of the great joys of life is how non-partisan, organic self-interest and creative impulse are.

GDP goes up, goes down, stays up, stays down, disappoints, outperforms, and whatever else it does, as a measurement of a gazillion things happening in the economy. And the amount of those gazillion things that are on a string held by the President, I could count on one hand.

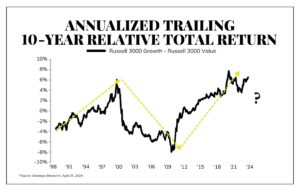

Chart of the Week

A decade of growth over value, a decade of value over growth, rinse and repeat, cycles play out … It is not merely a three-decade trend of such alternation but really has played out for quite some time. Do I believe the decade we are in will be a decade for big cap growth going from quite expensive to even more so? Well, no, I do not. And many companies, trends, and re-pricings are already playing into this reality (some, not yet). But our bias towards the quality of reasonable valuation (in the context of dividend growth, of course) is not merely a current-year position. There is a decade at play here.

Quote of the Week

“If it sounds too good to be true, you can bet your bottom dollar that it probably is.”

—Ian Morley

* * *

I will start the week in the Newport Beach office on Monday, head to a symposium with our custodial partners from Fidelity in Florida on Tuesday and Wednesday, and end up back in New York City on Thursday/Friday. April will soon be complete, and the glorious month of May will be upon us. Enjoy your weekends, let us know any way we can be of assistance, and enjoy your weekend.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet