Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I hope you will find this to be a special Dividend Cafe. No, this week’s Dividend Cafe doesn’t dare to bring the vast military sophistication of people who tweet all day long to you, but maybe we do one better.

We don’t talk about Russia/Ukraine at all.

Actually, there is some true connectivity between much of what I discuss today and how it interacts with current events, but at the core of the present market story, is the challenge of growth. Military conflicts, elevated uncertainty, spikes in commodity prices, and other undesirables do not help the growth story. But they are peripheral pieces to the story, not the story itself.

And today in the Dividend Cafe we are going to talk about growth, and all we are doing to make sure we never get enough of exactly what we need.

|

Subscribe on |

Russia/Ukraine and COVID Similarity

It may seem odd to write about anything other than Russia/Ukraine right now, but much like the COVID moment of a couple years ago, I am increasingly convinced that much of what comes out of Russia/Ukraine in markets will prove to be an exacerbation of trends and realities already in place, not new dynamics altogether. Energy prices were going up out of a supply/demand imbalance before Russia invaded, and that imbalance was merely exacerbated by the invasion.

Inversely, two years ago we had excess supply in oil markets as demand was slowing, and COVID served to exacerbate the slowing of demand (is that the biggest understatement of the year?).

Two different pre-existing conditions, and two different circumstances that poured kerosene on the pre-existing condition. But an accelerant, not a reversal, in both cases.

The world we were in before

Prior to COVID, and prior to Russia/Ukraine, we had a world experiencing the hangover of living above its means. Extended periods of excessive spending had compressed growth (see below), created mal-investment (see below), and forced a fiscal and monetary policy regime that perhaps added a short-term sugar high, but structurally made us more vulnerable (see below).

The two major news events of the last two years are classic accelerants, not paradigm shifts. Massive QE. Zero-bound interest rates. Trillions upon trillions of dollars of additional spending. Risk asset valuation increases. What was old was also new, only a lot more of it.

But inflation was new?

Indeed, as one would be hard-pressed to not hear or see, prices that had been quite moderated for quite some time (besides in housing, college tuition, and health care) suddenly spiked. Actually, those three price categories spiked more as well, but they were used to spiking. Pricing on goods and services moved higher as well over the last year, and the inflation narrative re-entered national consciousness.

Velocity by any other name

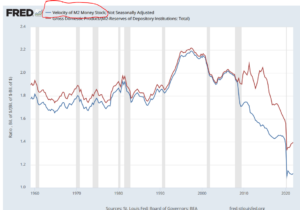

As energy prices skyrocket higher in the aftermath of the Russia/Ukraine war and supply chain bottlenecks continue to exacerbate the delta between demand and supply, the two leading inflationary challenges the economy faces, one factor serves as inflation’s great headwind structurally, despite the growth in M2 money supply of the last two years – collapsing velocity. A positive number multiplied by a negative number does things mathematically.

By the way, Japan’s money growth has been 10% per year forever, with 0% inflation.

Be careful what you wish for

This fact will prove to be the driving force of disinflation when the energy waters and supply waters clear. And no one is going to like it. This collapse of velocity is the textbook response of an overly indebted society. And it is not good. And it is counter-inflationary. The problem is, it is also counter-growth.

Household, government, and corporate debt is now 270% of GDP, not the 170% it was 25 years ago.

Sometimes I think Japan exists to warn the United States what happens when asset bubbles burst, when a debt-deflation spiral occurs, and what happens when a society stops having enough babies.

When Capital is Too Available

I have written forever of why excessively accommodative monetary policy is NOT the good thing many investors believe it is. I certainly understand why perpetual borrowers believe perpetually accommodative monetary policy is a perpetually good thing. But I actually think even they misunderstand economics.

I want readers of today’s Dividend Cafe to come out with a little more nuanced understanding of this subject than they had before they read it. We are living in a caveman understanding of monetary economics (“low rates good; high rates bad”). We can do better than talking (and reasoning) like cavemen.

What do you think happens if there is more capital available than there are good opportunities to put it to work? A better way to word it may be this – “what are the options of what could happen?” And before we look at those options, let me also nuance the phrase “good opportunities” to say “good borrowers.” Debt contains risk for more than what is done with it but also who is doing it (and the same is true of equity). So let’s try this again:

“What are the things that could happen if there is more capital available than either good opportunities or good actors to put it to work?”

- The excess capital is put into bad opportunities (i.e. mal-investment)

- The excess capital is given to bad investors/borrowers/actors (i.e. mal-investment)

- The capital ratios are altered across the whole economy (i.e. the more of other people’s money there is to invest – debt – the less equity that gets deployed; over time higher debt than equity alters behavior)

Back to Algebra

Savings = Investment (S=I). You cannot have a dollar invested that was not first saved. This is a tautology.

Investment (I) is a pre-condition for Productivity (P). And Productivity is a pre-condition for Growth (G).

Low yields discourage savings. But if S=I, and I is needed for P, and P is needed for G, then the algebraically unavoidable fact is that low yields compress growth.

Biting off your nose to spite your face

How do you get a continually increasing standard of living? By deploying capital where there is a higher Return on Invested Capital than there is the market rate of interest. This is where you get capital in pursuit of real projects, real growth, real productivity, and therefore, real improvements in quality of life. When Return on Invested Capital is below the market rate of interest you get pursuit of financialization – gamesmanship – front-running – but not productivity-enhancing growth.

The above concept is not really up for debate. Indeed, I know of no serious economist who would take exception to it. However, I do know some “serious” policymakers who have suggested the way to enact that economic truism is to artificially hold down the rate of interest. This begs the question about the “market rate of interest” – but worse, it delays the inevitable. Artificially low interest rates do allow for a Return on Invested Capital above the interest rate, and low rates also allow leveraging up this phenomenon to boost asset price returns even more. But there is a problem. Low interest rates kill the incentive to save. And over time, a lack of savings means a lack of investment (again, this is a tautology). This kills productivity, which kills quality of life.

Prove it!

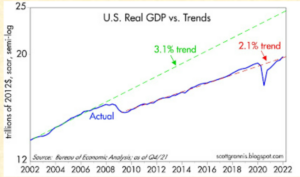

Do I have empirical support for the theory that low rates have stifled growth?

Chicken or egg? Yes.

This is the ultimate negative feedback loop – the defining hallmark of modern economic policy. An interruption to growth comes (business cycle, external circumstance, etc.) – and the treatment for such (excessive government spending, excessively accommodative monetary policy, etc.) put further downward pressure on growth.

Rinse and repeat.

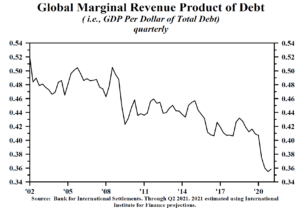

The diminishing return of excessive spending is empirically visible. Debt loses its multiplier effect over time.

Same song, same dance

The monetary side of the equation is not different from the fiscal one. Too much use of a given tool has neutered its policy efficacy, and now the need is there to reverse the policy tool, not use more of it. An interest rate that goes from 5% to 1% becomes massively stimulative in the aftermath of that movement. But as the disincentive to savings from such a move soaks in the piper has to be paid (unfortunately there is less savings to pay the piper with). And the further use of the tool to its desired end does the same thing that excess debt does in the above chart – it becomes counter-productive.

How to know what the Fed is going to do

The general narrative right now is that the Fed must tighten monetary policy (true). Some are willing to understand that the real problem is that they didn’t do it earlier, but for some, that is a bridge too far. But now the consensus thinking is that we face really unfortunate circumstances because (a) The Fed must act to relieve inflation pressure, and (b) Tightening when there is uncertainty like a war going on is problematic, and also, see A.

Well, I believe the Fed must act. I just believe they must do it for a different reason. But I will put that aside for the time being.

And I believe it is extremely convenient for people to say, “oh, it is awful to have to tighten when there is a war going on,” because it enables them to not have to say what they were going to have to say, which is essentially: “it is awful to have to tighten when __________ is going on.” In other words, there was always going to be something in that blank; for now, it is a war. But no matter what, the very thing Jerome Powell warned about when he was a QE3 skeptic in 2013 was always true: It is one thing to start excessive monetary accommodation; it is another thing to end it.

Signs for the Fed blinking

I believe the Fed will hike rates a whopping 0.25% next week, and I will be very surprised if they cannot get at least 50 more basis points done this year. Perhaps it will be more. But at some point, I expect one or more of these circumstances to be the catalyst to the Fed blinking …

- A yield curve inverting

- Corporate bond spreads blowing out

- The dollar strengthening too much

- The VIX increasing too much

As I have written before, the public cover for blinking will be disinflation, but the private catalyst will be the above circumstances. We have seen this movie before.

Back to Russia/Ukraine

The U.S. has exposure in this conflict as energy prices continue to rise, but also agricultural commodities have skyrocketed in price. And whenever you start weaponizing your currency towards a foreign policy aim you invite potential risk (which is not to say I oppose the sanctions – I am all for them – but I recognize the trade-off in signaling to other nations that we can freeze U.S. dollar assets in our geopolitical aims). The dollar has enjoyed a bid now (as it generally does in periods of risk-off), and that hurts multi-national businesses (who might also be facing the double whammy of lost revenues as they cease business in some pockets of the world, most notably Russia).

Global skittishness about commodities, the dollar, and multi-national business lines. In other words, some modest hair on the story of …

Growth.

Conclusion

I do not believe (at this time) that Russia/Ukraine represents a huge chapter in the book on stagnating U.S. economic growth. I believe the major components of that story are embedded in the remedies we have attempted – excessive debt and overly accommodative monetary policy.

I think we have saved too little to drive investment, and then further disincentivized savings with zero rates.

I think we have kept zombie companies around that divert resources and allocation of capital from good growth opportunities to themselves, further hurting productivity.

And yes, on the margins there are potential headwinds to growth out of Russia/Ukraine.

And in the end, the solution to all that ails us economically will continue to be the one thing we are most struggling with: Economic Growth.

A recovery of economic growth gives us geopolitical leverage (China, Russia). It gives the Fed bandwidth to start normalizing and restoring protective capacity. It adds to the tax base to start reducing debt. It even solves many of the social, cultural, and political dysfunctions we face. It solves for inflation. It solves for deflation. It solves for so, so much.

And it is so much easier said than done.

Chart of the Week

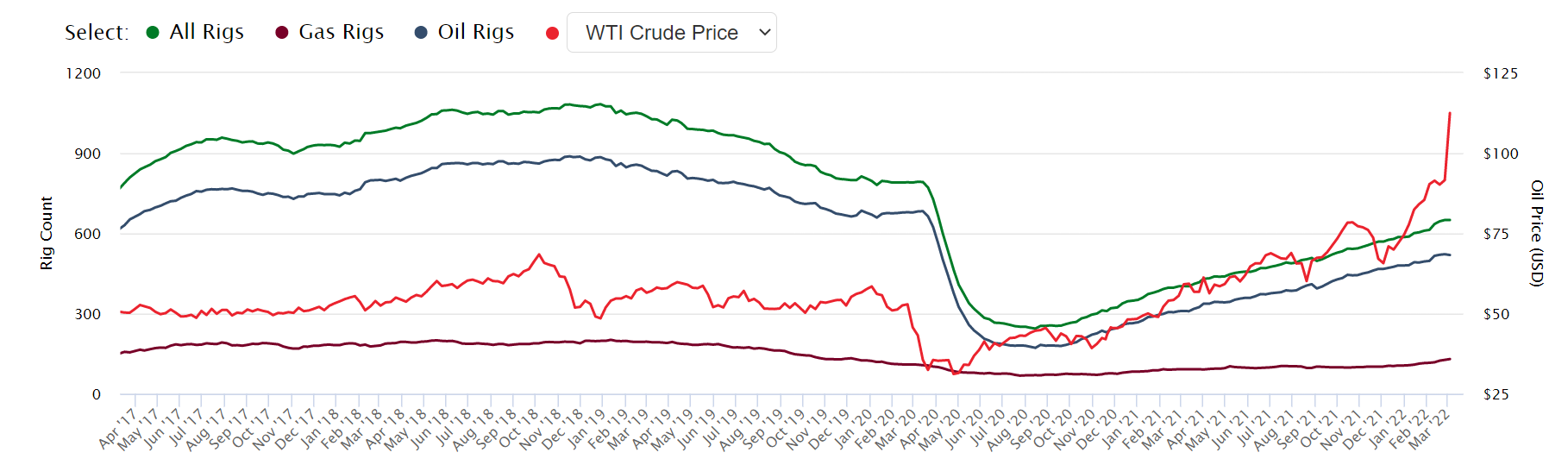

The relationship between oil prices and our rig counts may have been too liberal five years ago, but that the rig count contracted way below a sustainable level for needed supply is indisputable. And then to see the inversion of oil prices to rig count (vs. historical relationship) is screaming for a cure to the imbalance. I vote for growth.

*OilPrice.com, March 11, 2022

Quote of the Week

“Every investment price, every market valuation, is just a number from today multiplied by a story about tomorrow.”

~ Morgan Housel

* * *

I hope today’s Dividend Cafe brought some information and perspective that enhanced your understanding of the market and the economy. And I welcome your comments, questions, and interaction, any time.

As we enter the glory of March Madness this coming week, perhaps the greatest sporting event ever concocted by mankind, may our economic focus be on growth, even as we root for the underdogs in our brackets. Underdogs are the story of March Madness, and you know what? The underdog mentality has been the source of some great growth triumphs in our economic history as well.

Be of good cheer.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet