Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Last week, I wrote about investors’ reality (especially professional investors) being a by-product of the era in which they came to be. The intent was to set the table for how much of my investment worldview was formed. I live with a deep fear of excess valuations, and I live with a deep cynicism of the madness of crowds. Both of these things come from years and years of abundant research. But at the foundation of that research was the experience of living through something that provoked such impulses.

I won’t re-hash all of it this week. What I want to do this week is go beyond those two topics (i.e., valuations and crowd madness). We will look at these two things and seek to understand something about both concepts, but more importantly, we will seek to apply what it may mean to the present investing landscape and what it doesn’t mean.

This week’s Dividend Cafe wants to analyze a handful of present investing landscape realities, consider the lessons of history, assess where certain things are clearly different right now, and apply what it ought to prudently mean for real-life investors with real-life goals and real-life emotions, right now.

It is, indeed, our thesis that a rotation is in motion within investment markets. But I believe that means something very different than what many are saying it means. This week’s Dividend Cafe seeks to provide clarity around what is a truly important subject in 2021.

First things first

When I wrote last week of cyclical reality that value and growth have alternated taking turns as the market’s leadership sector for over forty years, I was sharing something that I assume all investors know. Growth has substantially outperformed value in recent years, and growth and value have performed in line with one another longer term. This alternating of the leadership mantle is the rule, not the exception. Growth’s outperformance of value in recent years has been deserved. Easy monetary policy has put a justifiably higher valuation on higher growth assets, allowing P/E expansion (multiple growth) to drive higher prices in growth assets. But it is a cop-out to credit the whole thing to declining interest rates. Stunningly successful innovation, maturing business models, captive revenue streams, business execution, and more have led to spectacular returns. Those two things an (embedded increase of valuations and successful business enterprise) combined with the technical reality of market indexing to form a perfect storm for mega-capitalization high growth companies.

This is the precursor to what we write about today. Our objective is to evaluate the present and the future.

Trying to Get the Measurements Right

With technology now representing just shy of 40% of the S&P 500, yet only accounting for 6% of nominal GDP and 2% of the labor force, it does seem prima facie acceptable to believe some of these ratios require adjustment. Now, there is no reason to believe the weighting of a sector in the stock market should be or ever would be proportionate to its weighting in the economy, as growth expectations, sentiment, profitability, and all sorts of other metrics blur the lines between the two.

The question is not whether there should be a delta between the two – there should be – but rather, whether or not that delta is over-stated or subject to compression.

Are market levels expensive?

On the one hand, if the S%P 500 gets to $170/share of earnings (and that is an ambitious but do-able target), that puts the S&P 500 at 23x earnings (forward multiple). So in best case earnings scenarios, the earnings multiple is really high.

But on the other hand, that multiple drops to 19-20x earnings apart from technology (h/t Yardeni Research). In other words, the multiple of the entire market is being elevated by 2-3 points (i.e., over 10%) by the tech sector alone.

Regardless of how one dissects all of this, markets are not cheap, and their relative expensiveness is primarily concentrated in the robust, high growth, impressive technology sector.

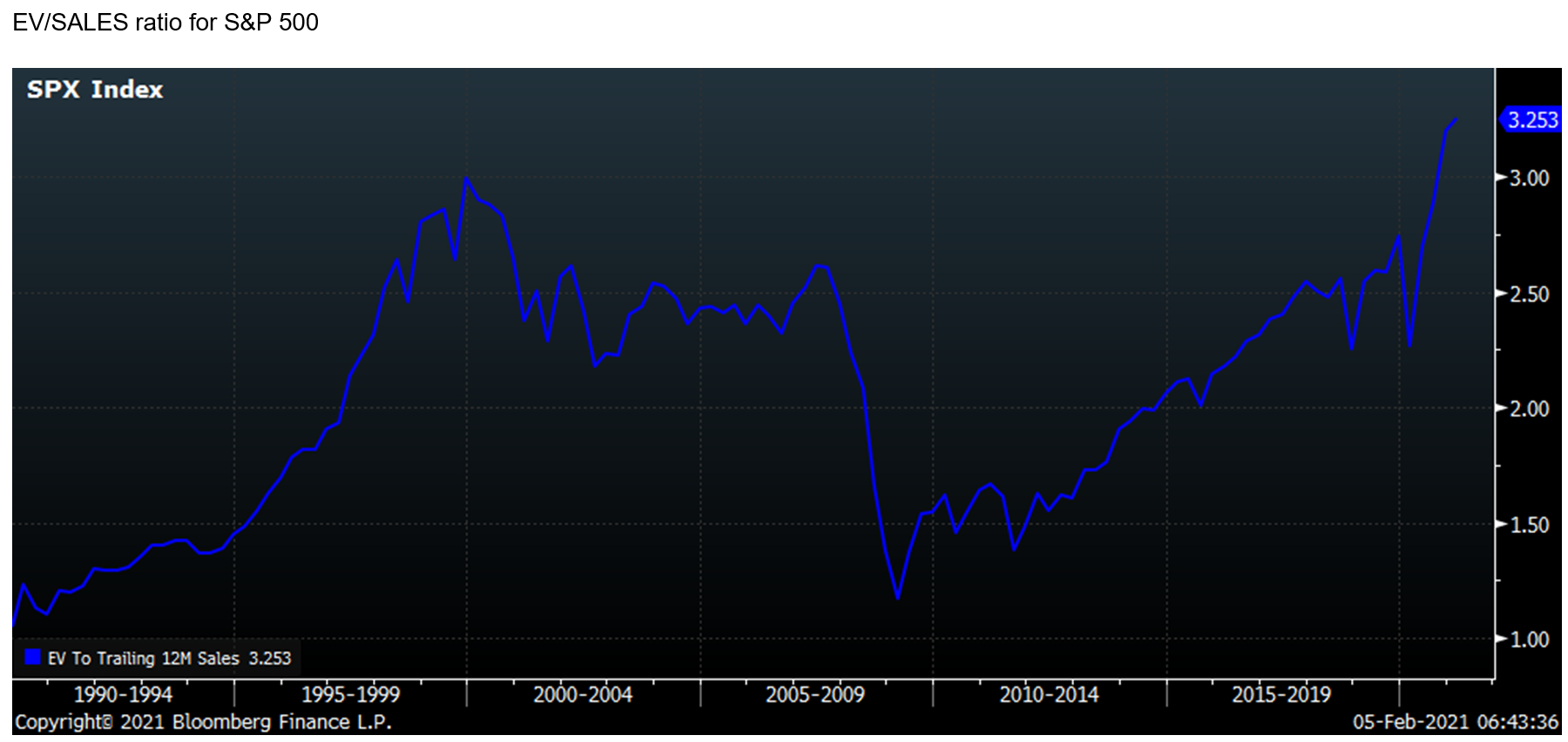

(This metric looks at the enterprise value of S&P 500 companies divided by gross revenues; it is a bit more useful in that the proper discounting of bottom-line earnings is made harder by such incredibly low-interest rates).

The Message of High Valuations

We know that valuations are high. And we know part of the high valuations are justified by low-interest rates.

We know that valuations are high. And we know that valuations have never been a useful timing mechanism.

I believe every comment I have ever, ever made about concerns regarding big tech, FANG, large-capitalization “growth,” or any other variation of these various themes has been chock-full of caveats regarding what I am saying and what I am not saying. I would summarize my view this way: The risk of significant value erosion is greater when valuations are higher than historical or sustainable levels; and, timing the onset of such value depreciation is impossible.

All of investing is the art and science of measuring trade-offs between risk and reward. An investment can return 2o% per year for a decade straight and still be a wholly inappropriate investment for most investors. One’s tolerance for value depreciation has to govern the decisions they make in pursuit of return. I believe investments trading at five standard deviations above their historical valuation can trade at six standard deviations above their historical valuation (which would result in further value appreciation for those holding those investments); I just don’t believe that can happen without the risk of a mean reversion whereby that investment gets pulled back to its historical valuation (even if that historical valuation itself is gradually moving north). It is the risk of that value recalibration that investors are wise not to ignore.

Volatility vs. Capital Erosion

The general worldview we invest with is one of avoiding permanent capital erosion, period. Yes, the historical era in which I grew up as a professional investor matters here. Up-and-down volatility in broadly diversified portfolios does not concern me, primarily because I know the lengths to which I go to obsessively explain to clients the reality of volatility.

But the Nasdaq crashing ~70% and staying underwater for over fifteen years is not something I should ignore. It is not possible to interpret that event of 2000-2015 as mere “market volatility.” And it is arrogant and dismissive to assume that every single thing is different than this time.

A lot is different. History doesn’t, and won’t here either, perfectly repeat itself. I get that. But there is a perfectly logical and coherent reason to at least look for similarities, and be wary about repeating various mistakes (or things that rhyme with past mistakes).

Excess on the margin?

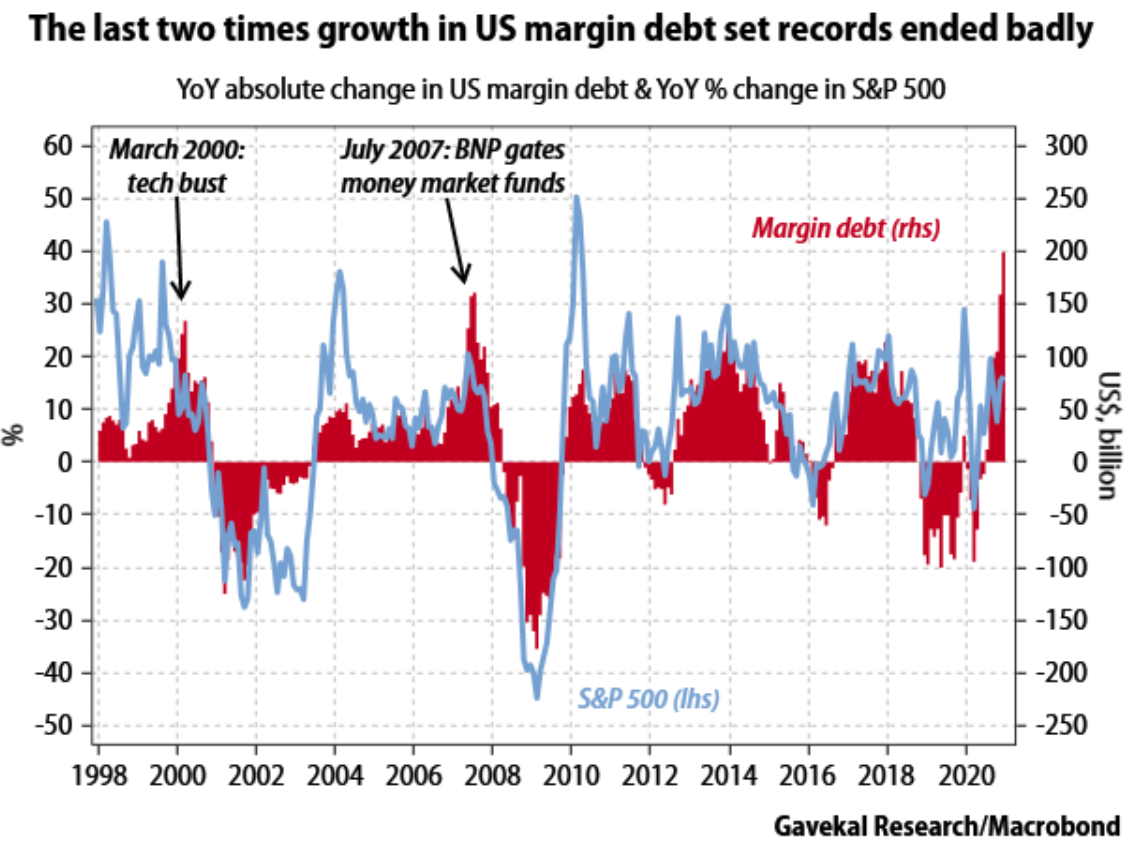

One of the measurements most connected to evaluating past periods of “froth” or excess – an indicator that was quite historically prevalent in advance of the last two significant market corrections – was growth of margin debt. And we certainly are seeing explosive growth of such now.

However, there is a huge caveat right now that I believe warrants further analysis before over-doing this application. Past explosions of margin use were almost entirely for the purchase of the very securities collateralizing the margin debt, but I am not at all convinced that is the case now. The advent of margin debt as a non-purpose lending vehicle certainly distorts the comparative benefits of the data. Comparing the use of margin debt to buy more Pets.com with margin debt to re-finance mortgage debt is textbook apples-to-oranges.

So, we’re left with the worst kind of data dilemma – where we know there is a data point that matters, that has to be factored into our understanding and concern, yet has enough hair on it that it does not give us the clarity we may be seeking.

Apples-to-typewriters?

Additionally, the Fed was raising rates even as margin balances were rising in 2000 and 2007 (that was a real commitment to froth). In this case, people’s margin debt is as close to free as ever – meaning, while that being purchased may be a reflection of euphoria and excess, it is certainly in line with the low cost (no cost?) of capital made available by a 0% fed funds rate. In prior times it was in the face of a high cost of capital – a pretty different tale.

Where can that clarity be found?

I do not believe there is anything more useful in understanding the skewed risk-reward relationship in today’s growth positioning than the one-sidedness of the euphoria behind it. Put differently, if this is a time where the “crowds” have gotten it all right, and it is going to sustainably stay that way for years to come, it is the first such event of its kind in history.

If no one calls the cops, can’t the party continue?

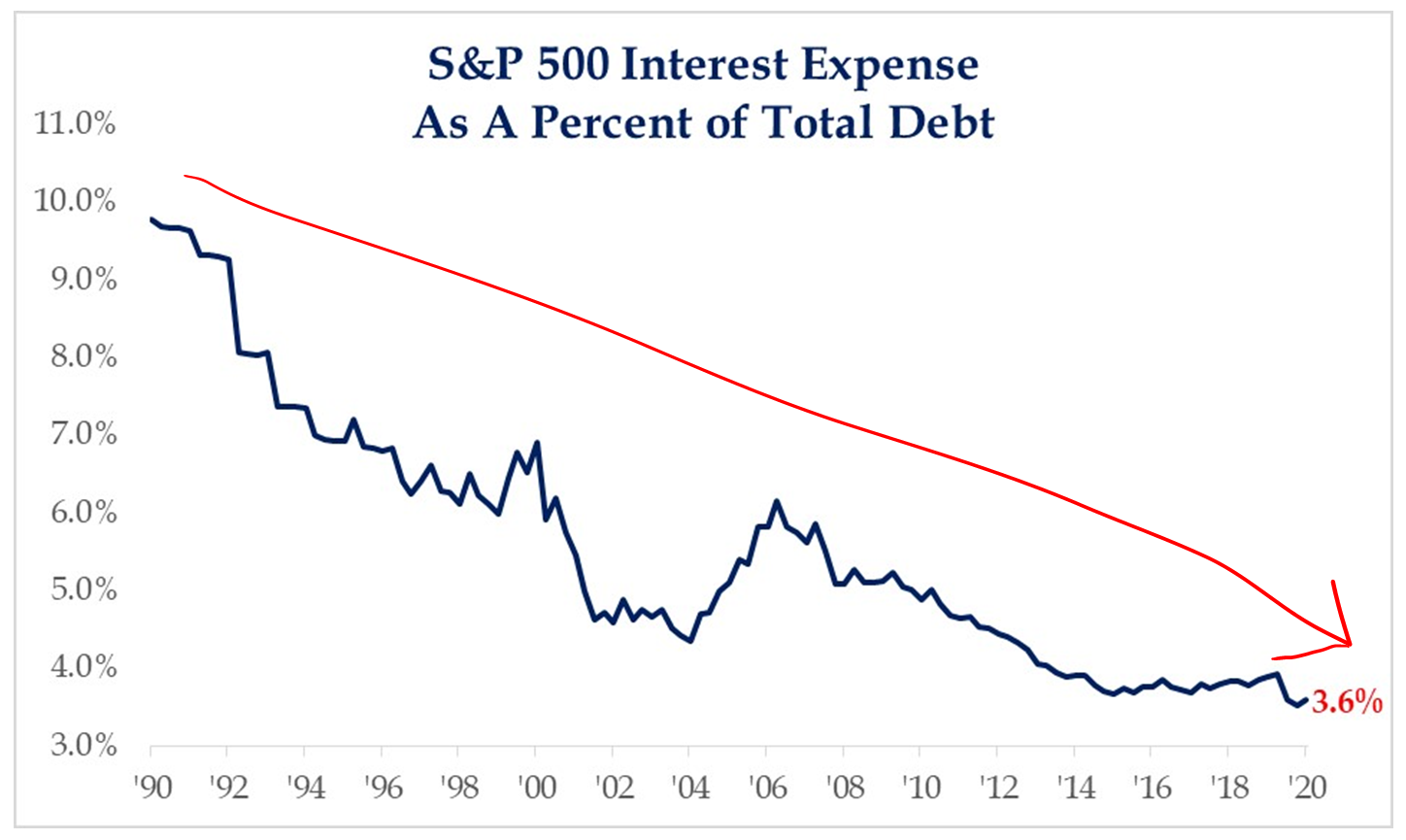

It is so important to understand some of the tailwinds equities have enjoyed that they simply cannot continue to mathematically enjoy going forward (because of, well, math). Interest expense as a percentage of company expenditures have gone lower and lower and lower for the better part of thirty years now (even as debt levels have increased 400%!!!), due to the decline in interest rates. Now, those rates may very well stay very low (in fact, I fully expect that they will do so), but what they can’t do is continue to decline as a percentage … This represents a lost tailwind, on the margin.

*Strategas Research, Investment Outlook, Jan 28

What is “value investing,” anyways?

If we use really traditional and basic definitions to set the table here, value investing is … (a) Buying something only when it trades at a ‘discount to its intrinsic value’ (i.e., a “value”); (b) And defining the intrinsic value through the company’s cash flow generation (current and future). Discounting those future cash flows into a present value provides one a number, and that number is either higher than or lower than (or equal to) its present market value. The “Buffett” model discounted future cash flows to define value (still does). This is all easier said than done.

Buffett’s mentor, Benjamin Graham, tended to look at companies trading at a discount to their “book value” as the definition of value investing (less cash flow and income statement centric, and more balance sheet and liquidation value-centric). I love this concept in theory and believe a sum of parts analysis of a company’s balance sheet can tell you a lot about its value. As I learned the hard way during the Great Financial Crisis, the problem is that “book value” is all well and good until it isn’t. The mark-to-market valuations of key assets on complex balance sheets make such an “asset valuation” hard to define. It is easier with companies whose assets are more factory, inventory, real estate, and lease driven; it is much harder when valuations are more, shall we say, subjective.

Whether one takes the “cash flow” approach to valuing a business or the “balance sheet” approach, I this basic summary that Charlie Munger used is as good as any I have ever seen to defining Value investing:

“Great businesses at fair prices.”

Simple enough, right?

Getting practical and personal

I am very comfortable with the concept of “value” investing as defined above, even though I believe some parts of this conversation are unhelpfully ambiguous. And I will unpack in a moment how I have solved for that ambiguity in my own process … But here is where I believe “value investing” offers universally helpful criteria for investment selection:

- The price paid for a business matters

- What is being bought is actually a business, not a trading card or paper

- Whatever a company’s real value is, it is defined by some fundamental metric, not totally incoherent platitudes devoid of any limiting principle (more of this in a moment)

- A process and discipline are needed to stay in the category of “investing” versus the category of speculation/gambling. Hoping and cheering are not investing behaviors.

Taking the fun out (or back in?) of fundamentals

Truly outstanding managers like Buffett have always been able to transpose to their reading of fundamentals an appropriate weighting on competitive advantages. Management talent is hard to quantify, but few things matter more than management talent when one assesses business execution economics. Creating earnings growth is at the core of free enterprise, but assuming it happens in a spreadsheet model is different than affecting the decisions necessary to make it happen. Some businesses have more inherent and stable advantages than others. Some have more uncertainty and risk than others. These things get factored into valuation, multiple, ratios, and so forth. Markets price these varying uncertainties and realities is based on upside and downside calculations. But really, what we are talking about here is allegedly the distinction between Growth and Value, when in reality, it is clearly a difference of degree, not kind. What ends up as a market price is supposed to be an investor’s assessment of the company’s earnings capability, and some companies offer a lot more variance as to what that earnings capability maybe than others.

But but but …

I hope you are following me so far. High valuations on high estimates of high future earnings power is one thing. But that is categorically different than saying no valuation of future earnings power is needed because everything is different now. Saying a price will go higher because prices have been going higher is incoherent, it is demonstrably false, and it has decimated investors for years and years and years. Prices go higher until they don’t. But if prices are not going higher because of some reasonable (and hopefully accurate) assessment of future earnings power, it is a glorified Ponzi scheme, or greater fool theory, or at best, wishful thinking.

Limiting principles deja vu

The most spectacular “unicorn blow-up” of the last few years featured 90% or so of the value being written down of a massive shared office space company that was heavy on brand and heavy CEO charisma, but really, really light on earnings, or a path to earnings. There was a lengthy period of time where investors were willing to invest based on a kumbaya nonsense about peace in the universe in such. I guess it is harder to calculate the intrinsic value of peace in the universe than it is rental income. But my point is this – once one says, “everything is different” or “profits don’t matter” or, God forbid, even “future profits don’t matter,” they may as well invest in “peace in the universe,” because there is no limiting principle to that forfeiture of common sense and rationality.

Some things are different

It is harder to assess value in a fast-moving and technology-forward world than it used to be. I do not believe investors need to forfeit the search for truly special businesses that can create future earnings which discounted into the present are tremendous growth companies, even the present multiple seems uninvestable. I do think that needs to be done within the context of risk tolerance, cash flow needs, and specific investor goals and liquidity profile, but I fully believe that there is more room for “broader bands” around the way we look for competitive and special companies now than there ever has been.

But, but, but again

If we are being honest, though, applying much of the present phenomena of “growth investing” to “searching for special innovations, talent, and long-term earnings bonanzas” is NOT REALLY what most people are doing. They are shopping for momentum, period. They are looking to own today and tomorrow something for no other reason than what it did yesterday. That is not value investing, but it isn’t growth investing either. It is rearview mirror investing. And it is a grotesque violation of our fiduciary duty.

So what we do and don’t do

Whether you call it growth or value investing, an investor does business analysis. A gambler obsesses over “price action.” I will take any distinction between growth and value one wants, and compare advantages around book value and P/E ratios and historical returns and all those things any day of the week, as long as we divorce those healthy and necessary processes (whether they lean towards “growth” or “value”) from momentum speculation.

People did not buy the Nasdaq in late 1999 and early 2000 because the CEO of [fillintheblank].com was a new Thomas Edison and the magical sunlight of the company’s destiny was sure to bring nirvana to the morning dawn. They bought that horse manure because they were tired of it going up in price without them.

And then they got their faces ripped off.

Conclusion

We have a very potent portfolio approach at The Bahnsen Group we call Growth Enhancement that incorporates “growthy” investments. The focus is on companies. We abhor the concept of momentum. It goes into emerging markets. It goes into small-cap. It is innovation-driven. It strives to not overpay in the present for what it hopes to get in the future. But it is “growth” oriented and not cash flow or dividend or value-oriented.

It also is not for everyone. It will be more volatile. And it will suffer disappointments. But it is a fundamental way to INVEST for growth, not hope or gamble for momentum.

It is a complementary investment strategy, not a core one. At the CORE of our investment methodology is our version of seeking Growth AND Value – dividend growth. It puts less burden on guessing who the next Thomas Edison will be and more burden on analyzing cash flows and what management is telling you about their company from those cash flows. It is biased towards mature companies, which implicitly means it is biased towards stability. Guilty as charged.

That is what our clients ask of us.

Sometimes companies with a low valuation deserve such. Sometimes a really superior (and subjective) judgment is needed to assess what can not be computed in traditional ways. Dividend Growth gives us a way to do this without the constraints of value investing and the randomness of speculative investing.

Some valuations today are cartoonishly excessive. Some will prove to be perfectly justifiable. One’s tolerance for being wrong in those assessments sits at the heart of the risk/reward trade-off. Through all of these complicated processes, our goal for our clients is to compound the capital of those accumulating their wealth and create uninterrupted cash flows for those withdrawing from their wealth.

We do not want to be wrong about guessing when superior growth rates are already priced into a stock or not. We humbly recognize the historical consequences of getting that wrong.

We keep an open mind about Growth Enhancement while delivering on our CORE INVESTMENT OBJECTIVES through real businesses delivering real dividends.

To that end, we work.

Quote of the Week

“There is a fool in every market. If you don’t know who it is, it is probably you.”

~ Warren Buffett

* * *

Please join us for our next national video call at 11:00 AM PT / 2:00 PM ET Monday, February 8th. We will be recapping January’s market action, looking at some of the recent craziness and volatility in niche parts of the market, and offering perspective on the economy and market outlook as we get deeper into Q1. I really welcome your questions and thoughts on all of this, and we will devote our Monday call to this subject.

Can Tom Brady do it? You talk about the perfect definition of a growth stock and a value stock … That guy warranted a very high P/E in 2001. But that was still because of fundamentals. He was a deep value and a high growth pick.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet