Dear Valued Clients and Friends –

I did something today I have not done with Dividend Cafe, ever. I just wrote it. I just sat down and started typing, and wrote it, all the way through. I didn’t cover ten or fifteen or twenty topics like I usually do. And I didn’t write some parts on a Saturday and other parts on a Tuesday, adjusting for new market action on Wednesday, etc. I wrote in one sitting an entire treatise on what I believe is the great paradigm to understand in the years to come for investors. Don’t worry, I went back and added some sub-titles to “break it up” a bit, but it really is one topic all the way through.

I really hope it will inform you, guide you, challenge you, and to some degree, edify you. I also hope it will provoke you to reach out with any questions you may have. We invest for the world that is, not the one we want. And some years, the delta between those two seems wider than other years.

Jump on in, to the Dividend Cafe.

The new normal in six words

There is a principle at play in all aspects of the economy right now – from fiscal policy to monetary policy to regulatory policy to state and county medical policy to nearly any category of public life – and that operative principle adopted by virtually anyone with any power or influence is, “don’t just stand there, do something.” Even in a multi-month situation where no “fourth” stimulus/relief bill has been passed, there is no credible person who believes the lack of legislation (yet) means anything other than a delay until after the election so the prevailing party can get more of what they want in the package and less of what the other party wants. The point is, policymakers plan “to do something” (in this case, to do something, for the fourth time).

Why do we care?

What will most inform investors is if they can understand the connection between this reality and the economy, the things that impact the investment landscape, and their portfolios themselves. The principle of “doing something” – heavy intervention – is primarily a fiscal and a monetary and a regulatory reality. Understanding the micro and macro impacts of the fiscal, monetary, and regulatory domains of society will give us great intelligence into how to think about portfolio positioning for many years to come.

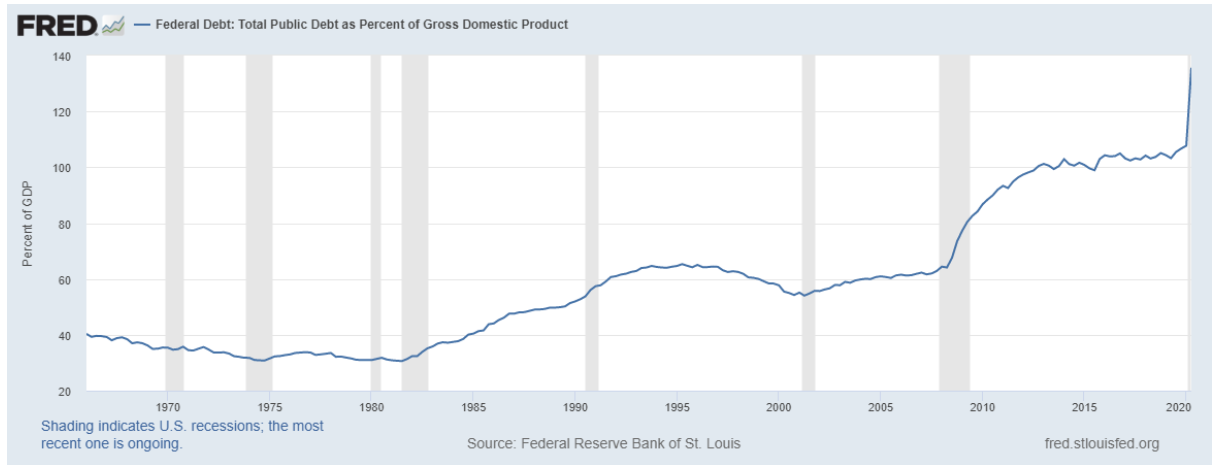

A necessary truth inside fiscal reality

Heavy intervention (fiscally) may be useful at times, it may be defensible at times, and may be unacceptable at other times – but it is not my purpose (at least here) to draw conclusions around what fiscal interventions are good and useful and when. My only intent right now is descriptive (what is), not prescriptive (what ought to be), and descriptively, it is my assertion that significant fiscal interventions means greater budget deficits and greater size of government as a part of the overall economy. Therefore, the inescapable conclusion is that there is a decidedly deflationary bias in the economy because the government’s greater role can only come from one place and one place alone – by “shrinking” the role of the private sector. Why is that? The government’s only source of money is TAXATION (money taken from the private sector today) or BORROWING (money taken from the private sector tomorrow).

None of this is to say it is a good thing or a bad thing (again, at least not here). And in fact, all sane people know the government has some legitimate role in society. I am merely explaining that there is a necessary feedback loop at play here. Government spending grows as part of fiscal policy decisions (COVID/Cares Act, ObamaCare, Financial Crisis stimulus, war decisions, etc.) – and the private sector’s percentage of the total economy shrinks.

How the pie is cut

This is why the size of the economy is not the primary relevant data point in an understanding of headwind or tailwind pressures on growth. Merely saying that we have a $21 trillion GDP does not tell you what percentage of that economic engine is government spending vs. private sector activity. The ratio between the two is far more important than the overall size to gauge where an economy is headed.

Connecting the Dots, Part I

So as the increasing fiscal policy takes hold (“don’t just stand there, do something”), the increased government spending removes moneys from the economy where it can be argued they will be more productively used. Of course, many government expenditures are a necessary cost of business – a cost of having a functional society. The statements here are not arguing for anarchy, or even in this context for a more limited government (though I certainly believe in the latter). They are just establishing economic truisms, that as we move money from “best and productive use” (defined by the laws of free exchange in a market system whereby rational actors pursue their own self-interest) to those areas that are “policy-driven,” we do sacrifice some productivity. This is why the multiplier effect on money in the private sector is so much higher than money for a government program – it doesn’t mean the government program is not needed; it just means it multiplies into less than does the alternative.

This is why the growth of government spending has proven to be dis-inflationary in Japan, Europe, the UK, and the United States for thirty years – because money has been re-directed and done so via debt spending, not only limiting the productive use of capital but spending the productivity of the future, today.

Connecting the Dots, Part II

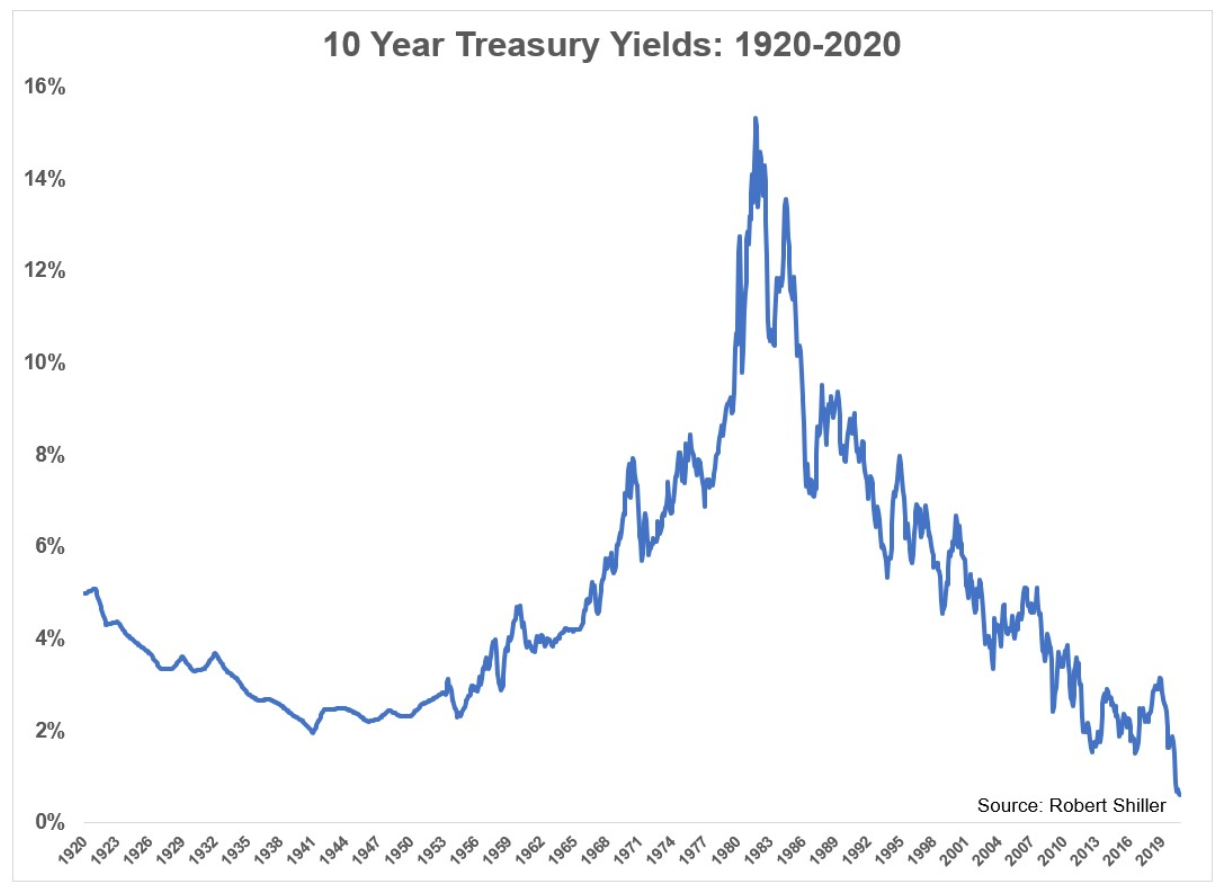

And therefore, with this fiscal dynamic lingering out there, another opportunity to “not just stand there, but do something” enters the fray – monetary policy. Central banks have had ample opportunity for intervention and action in the last 20 years. First, central banks turn knobs to help accommodate the economy during times of concern (i.e., in advance of alleged Y2K fears, Greenspan turned the liquidity spigot on; then again after 9/11; etc.). But central banks can’t just respond to the ad hoc moments of crisis in the news cycle – they must also set the rate terms by which the whole economy can function, and after the financial crisis, it was deemed to be rule numero uno that borrowers have access to (a) Lots of liquidity, and (b) At a really low cost.

And then there is the reality of government borrowing, where new borrowing means more expense unless the cost of debt is brought down as the amount of debt is brought up. $10 borrowed at 4% costs the same as $20 at 2%. This principle is alive and well in our economy, with one small detail that may not get a ton of attention … either the money has to be paid back, or the borrowing can’t go on forever.

Actionable Conclusions

What this means is that the “must do something” world of policymakers is forced to do something, and then do something about what they have done. And then again. And then again. Heavy periods of monetary intervention exacerbates a boom/bust cycle, and each bust requires interventions that create more boom, and each boom makes the next bust more painful. Rinse and repeat. What would I conclude from this multi-decade reality of feedback loops and policy commitments?

(1) Asset-rich members of society fare better

(2) It becomes harder to see and decipher real value in risk assets through the noise of interventions, but that real value is the greatest protection one has from the pain of bust cycles

(3) The only remedy for the challenges these policies create is more of the same – if heavy monetary accommodation creates certain mal-investment in the society, the antidote to the pain of mal-investment is … wait for it … more monetary accommodation.

Deja Vu all over again

The “monetary accommodation to treat the consequences of past monetary accommodation” is only one side of the coin. Remember a few paragraphs ago when I talked about fiscal policy, too? Well, it turns out, the same dynamic is at play there – more fiscal intervention begets more fiscal intervention just as it does on the monetary side. Plus, as we have learned from COVID, the “must do something” mantra has a hard time finding a limiting principle. There is plenty of room for debate as to what exactly should be done right now above and beyond the $2.2 trillion CARES Act that has already been done, but regardless of whether or not one supports additional spending for state and local fiscal relief, targeted support to airlines, targeted support to restaurants, a re-load and re-purposing of the PPP program, greater resources for schools and hospitals, direct payments to taxpayers, enhanced unemployment, etc., does anyone doubt that more of some of these things (if not all) is coming? It may be before the election, and it may be after, but the principle at play is – your first government intervention will not be your last.

It cost a lot of money to try and help the economy from the top.

One more thing not yet covered

If it sounds like I am arguing that we live in an age where we will see more fiscal interventions, you are correct. There is very little pressure on policymakers to “don’t just do something, stand there.” The expectation from voters is that there will be interventions, and as I have argued, interventions beget more interventions.

And yes, I am arguing the same on the central bank/monetary side as well. The policy experiment to heavily reflate markets post-financial crisis with liquidity worked, meaning, it reflated capital markets. But it also did something else – it made the economy more vulnerable to the impact of a reduction in liquidity in the future. Credit markets are fat and juicy right now thanks to post-COVID monetary action, but that also has emboldened the patient to take more medicine, upping the ante for when the patient might be medicine-less in the future.

So it behooves us to understand that the great paradigm shift of the 2020s is not merely more fiscal policy or more monetary policy, but primarily, the integration of the two – an accord between the fiscal and the monetary, the likes of which the world has never seen.

Some could wisely and accurately point out that Japan has integrated the two explicitly for quite some time, but Japan is (a) A $5 trillion economy, not a $21 trillion economy; (b) Not the world’s reserve currency.

At the nexus of coordinated fiscal and monetary policy will be the decisions that most impact the economy for decades to come here in the United States. This eliminates some volatility (divergence between fiscal and monetary policy) and exacerbates other volatility (the two are now aligned, so stakes are higher).

If at first, you don’t succeed, try, try again

Abundant levels of government spending that do not create the desired results never ever means reduced government spending; it always means more government spending. Extraordinary monetary measures that do not achieve desired policy objectives never means less of the prior measures; it always means more monetary measures – more aggressive acts – more experimentation.

Businesses that spend the moon on a given plan and do not succeed run out of funds; they hit a point where “doubling down” is not an option. Come to think of it; the same is true for the blackjack player where the expression “doubling down” comes from. But when you think about fiscal and monetary policy into the future, the tax-collecting authority and money-printing authority of the U.S. federal government and the Federal Reserve puts them theoretically outside the finite limits that most individual, business, and private actors would be subject to in this regard.

Yes, there are supposed to be limits such as the world’s confidence in the dollar, but that presupposes other country’s behaving differently than our own.

So what to do about all of this?

#1 – Abandon Indexing

For the foreseeable future, standard indexing is going to be an inferior way to invest risk capital. It is going to ensure that you are buying more of the larger companies and less of the smaller companies (because indexes are cap-weighted), and therefore that you are buying more of yesterday’s great performers and less of tomorrow’s great performers. The timing of when this inevitable law of nature takes hold is totally impossible to say, but what is not impossible to say is that laws of nature are hard to replace.

#2 – Recognize the Limits of Boring Bonds as a Risk Mitigator

With interest rates up and down the yield curve at or near the zero-bound, the ability of rates to “hedge” severe market volatility is limited. They can maintain their capital preservation characteristics without providing a spike in value to offset large decreases in value that risk assets will suffer in times of severe distress. This is relevant to a total asset allocation.

#3 – Appreciate the Role of Alternatives in Balancing Risk

Equity volatility is real and a fact of life for the long-term equity investor. The severe, sudden, and unsettling capacity for equity drops requires a part of one’s portfolio to be diversified in such a way as to limit that equity downside risk exposure. Alternative investments are needed, not just to the equity dynamics that concern investors, but to the bond market – where the current environment offers less utility in balancing equity risk than ever before.

#4 – In line with #1 and #2 above, but taken a step further, embrace Dividend Growth equities as an optimal alternative to indexing for the next ten years, and as a vastly beneficial alternative to bonds

A coupon from a bond is assured, or the bond is in default. But a dividend from a stock is not assured – a company can cease paying it if they so choose. A 0.5% yield on a bond and a 4.5% dividend yield is a spread of 4% between the two – meaning, an 8x increase in income from one to the other. Would you argue that an 8x increase is pretty good compensation for the risk of companies not paying you a dividend versus a boring issuer assuring their bond coupon? Put differently, would you argue that an 88% reduction in pay is a little steep for the benefit of knowing the coupon is coming?

And is that dividend really at jeopardy? Or can a diversified set of dividend-paying companies be invested in that have decades upon decades of a track record of not just paying their dividends through COVID and the financial crisis and 9/11, but growing the dividends as well?

#5 – Think Global

Whether it be income or growth, there must be an increased menu from which to order when investors are looking for the risk and reward attributes they want in their portfolio. While much of the developed world suffers from the same disinflationary pressures, the U.S. does (Europe, Japan, etc.), a broader world of equity, debt, real estate, and alternative possibilities offers more opportunity in the challenges of the decade ahead. The emerging markets are noteworthy here, of course, but are also not without risk, especially if dependency on ever-growing globalization is the investment thesis.

Conclusion

Be of the mindset that all you do in your portfolio is affected significantly by the decisions to “do something” that others make both now and in the future (and candidly, what they do now and in the future is affected heavily by what has been done in the past). Much of what gets done may prove beneficial and wise, and some will prove problematic. But investors are dealing with a world of intervention, not laissez-faire, and the implications suggest very different actions than broad market indexing and reliance on traditional bonds. We hope this has MAGNIFIED our thinking for you.

Politics & Money: Beltway Bulls and Bears

- There is no question that polls are increasingly showing a likelihood of a Joe Biden win next month, and it is entirely possible that markets are responding favorably at the possibility of a non-contested, non-controversial outcome. My instinct says that a close race is still possible and an election night concession from either candidate is highly unlikely, but I do remain of the opinion that markets are more concerned with “no outcome” or an “uncertain outcome” than either of the particular outcomes. More or less, the election is shaping up right now to essentially be a test of whether or not polling is worth anything anymore or not.

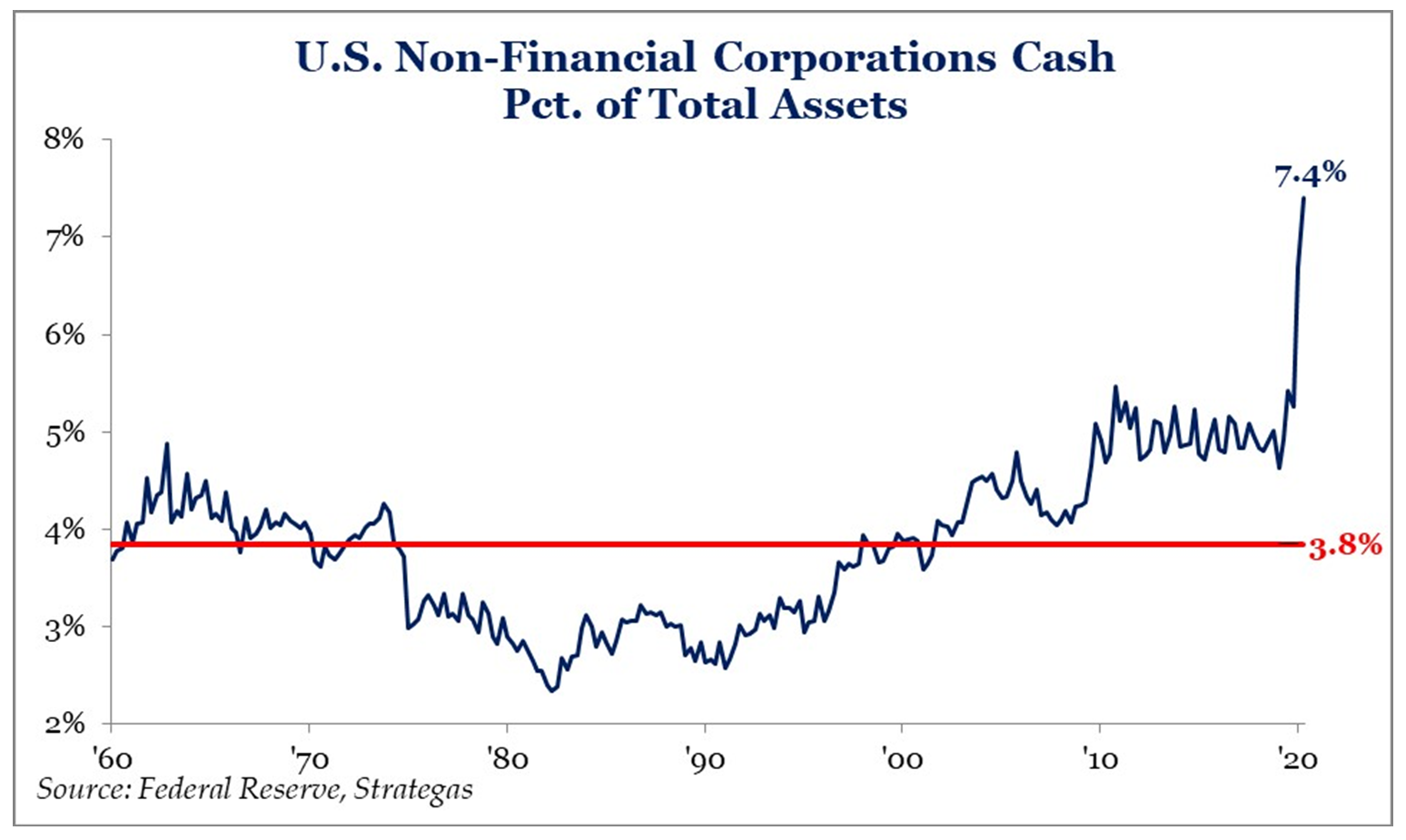

Chart of the Week

If a major part of our market thesis is that it will take a resurgence of business investment to drive economic activity and the profit cycle higher, it stands to reason that there will need to be a way to pay for that capex. The stunningly high amount of cash on company balance sheets, often a by-product of new debt issuance made possible by COVID era monetary policy, provides a reason for optimism. It is not that companies have to spend this cash on capex; it is more a question of what else could they do right now? A cash hoard has been rewarded; now, it is time to put it work.

Quote of the Week

“October. This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February.”

~ Mark Twain

* * *

Please do reach out without any questions you may have about this week’s commentary. I expect it will require more explanation and dialogue in the future. These things require contemplation and discernment. It is to that end that I work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet