Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I have written about excessive indebtedness many times in these Dividend Cafe pages, including a piece nearly two years ago that I think has held up quite well. Lately, I have written about Japanification, which is not quite the same topic (though there is certainly heavy overlap).

I have long believed in treating the disease, not the symptoms, and I didn’t even go to medical school (in fact, if I had, it seems these days I’d be less likely to believe that). That may be an overused cliche, but it has utility when it comes to how we think about our personal lives, our health, our finances, and so many other things. And when it comes to the issue of Japanification, I think the overall subject will be served to look with more granularity at the nature of the excessive debt to which I refer.

This is a seriously action-packed Dividend Cafe, and if you do not agree after reading it, you are entitled to a full refund of your subscription price.

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

How we get from A to D

The basic sequence goes something like this:

- An asset bubble forms from some combination of circumstances – call it excessive government stimulus, a prolonged period of easy money, investor euphoria, human nature, etc.

- The bubble eventually bursts, and great economic damage is done – profits collapse, wages collapse, jobs collapse – and in really serious situations, a debt-deflation spiral forms (that is, the attempt to reduce debt and leverage fails because the value of the assets/collateral is dropping at a rate faster than the assets can be sold to pay off debt; when asset prices are sold and debt is lowered, the borrowers have higher leverage than when they began this painful process because the denominator that is their asset base is reduced).

- To treat the problems of a bubble burst, whether they be mere contraction/recession or a more severe debt-deflation spiral, governments use the Keynesian tool of fiscal spending to offset this damage (a “counter-cyclical fiscal punch”), and central banks use monetary policy to soften the pain and accommodate an economic activity, primarily with a lower cost of capital.

- The lower cost of capital incentivizes more borrowing.

- The additional borrowing puts more of a drag on growth.

- More borrowing and spending means less savings and investment.

- All of these things facilitate downward pressure on growth, and all of them have their roots in excessive debt and leverage.

Someone has to pay

My treatments of this subject in Dividend Cafe have always tried to popularize the subject in a way that is readable and comprehensible, and that makes certain nuances difficult. For example, is the leverage in an asset bubble private sector debt or governmental? Is it corporate or household? Does it matter? Well, yes, it does. And it is entirely possible (as is my belief) that some events in history have been one more than the other.

A very conscious and deliberate belief post-GFC was that the balance sheets of American households were so impaired by the housing bubble burst (and secondarily by a corporate credit glut) that the balance sheet of the United States government needed to step in to “plug” the capital hole. It is not a wrong theory, but it lacks the more significant nuance of the specific balance sheets of the banking system, which was the real capital hole the government was trying to plug (with real ramifications for both household and corporate sectors).

But these things do not happen in isolation. It isn’t like from 2000-2007, U.S. households were on a borrowing binge while the federal government was attending a Dave Ramsey seminar (some of you know what that means). Put differently, we are not talking about one sector drinking too much and the other staying sober; everyone was sloshed, but when it was time for the patient to dry out, only one had a functional liver left (and even that only because of taxing and borrowing authority that most binge drinkers don’t have).

My analogies are getting confusing, but I think they work, so bear with me.

U.S. households binged on debt, mostly in the mortgage sector, into a housing bubble from 2001-2007. In that same time period, the U.S. government went from $5.6 trillion of national debt pre-9/11 to $9 trillion of debt before we got to the great financial crisis. So one actor grew their debt level by 61% in that period, and they were the more responsible actor called upon to save the world. Dear Lord. It is surreal to even think about.

Back when the national debt was peanuts

Now, that 60% increase in federal debt is not quite as bad as it sounds because debt-to-GDP only went from 56% or so to 62% or so in that time period – a by-product of the GDP growth (denominator growth) that was taking place as households were levering up and the government was spending extensively. You know what households were spending on – bigger houses they couldn’t afford and TV’s to put inside of them – the important stuff in life.

But what was the government spending on? The Afghanistan War and the Iraq War, yes, and everyone can have all kinds of opinions on those two wars and the way they were prosecuted. But of course, No Child Left Behind and Medicare Part D also went into effect in that time period, and again, people can have all kinds of opinions about those two pieces of legislation (passed on a bipartisan basis), but they were really, really expensive.

Left pocket and right pocket

So we get to the financial crisis with $9 trillion of national governmental debt, a 62% debt-to-GDP (in a thriving economy), and a household sector levered out of its mind. What does the household sector proceed to do from 2008 to 2013? Bring its total debt level from $13 trillion down to $11 trillion, and bring its debt service as a percentage of disposable income from 13% down to 10%.

And what does the federal government do in that time period? Bring its debt from $10 trillion to $17 trillion. $2 trillion of reduced debt in one hand, $7 trillion of increased debt in the other. Good trade?

We’re not all Keynesians now.

Just getting warmed up

The $17 trillion of national debt we would have in 2013, by the time the economy was ready to really “recover” and the initial few years of post-crisis efforts were complete, would prove to be child’s play for the decade to come. The number would be $20 trillion by the time President Obama left office (it was $10 trillion when he arrived). Then before COVID came, the national debt would go from $20 trillion to $23 trillion. Are you doing the math here? We basically added $1 trillion per year to the national debt between the time that we were “done” dealing with the financial crisis and before the time that COVID became a thing (from the end of 2013 through the end of 2019). No economic event. No geopolitical event. No Keynesian stimulus. No pandemic. No national emergency. No global circumstances. Two Presidents – one Democrat, one Republican. And more national debt accumulated in those seven years than we had accumulated in the first 225 years of our country’s existence.

But then, COVID.

$23 trillion became $28 trillion in a year. And now we sit at $31 trillion. And we talk about another $1 trillion per year as if it is a given.

No emergency. No Keynesian stimulus. No crisis. Just another $1 trillion per year, sometimes more. You get the idea.

Pretty soon, you’re talking about, well, $31 trillion.

The “everything is fine and normal” spending

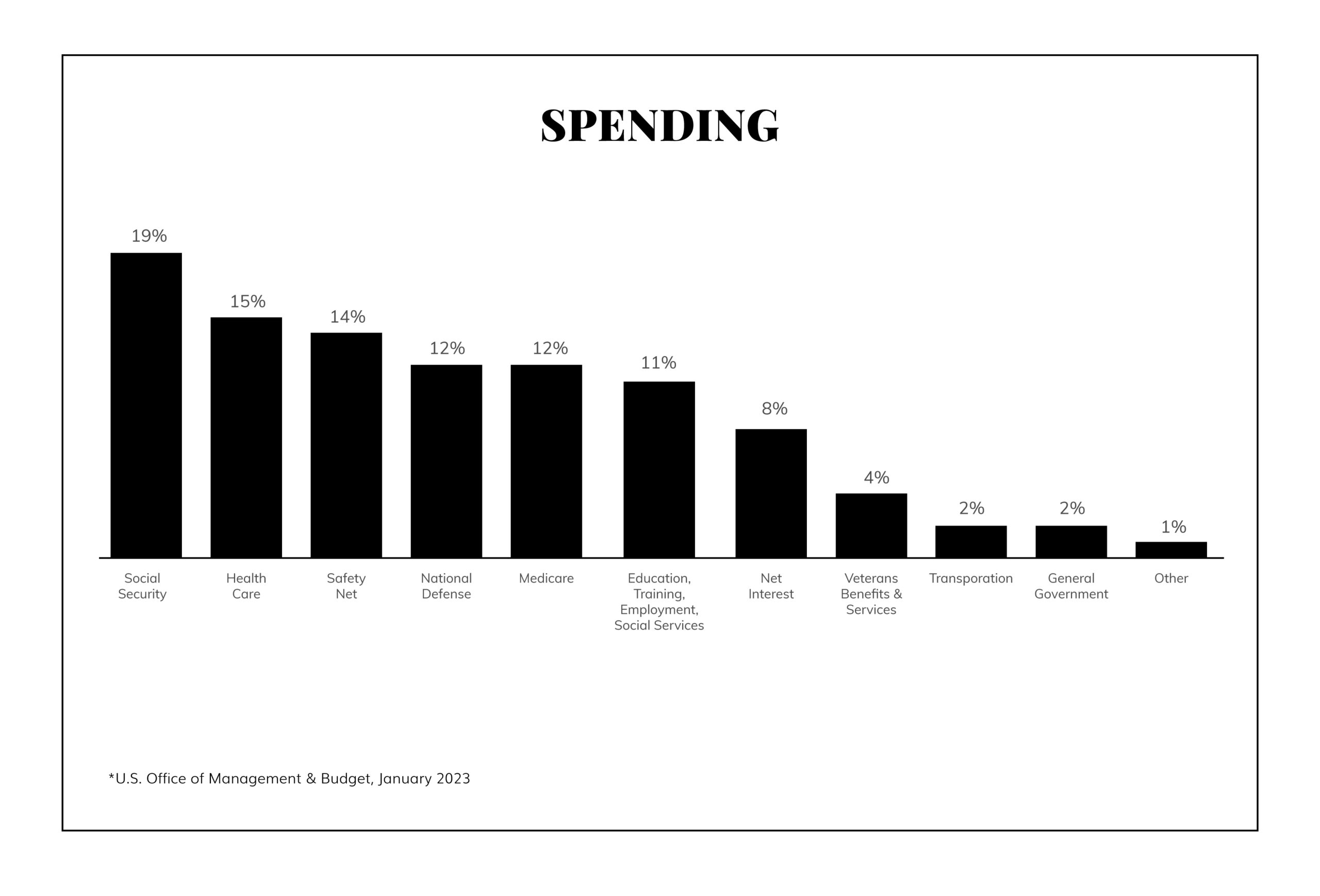

Here is what we spend money on right now, without a stimulus, a crisis, an emergency, or any of that kind of stuff:

So 60% of our outlays go to transfer payments. Does that sound politically easy to lower?

12% goes to the military while we sit with massive wildcards in NATO-adjacent Ukraine and Chinese threats to Taiwan. Does that likely (or wise) to go lower?

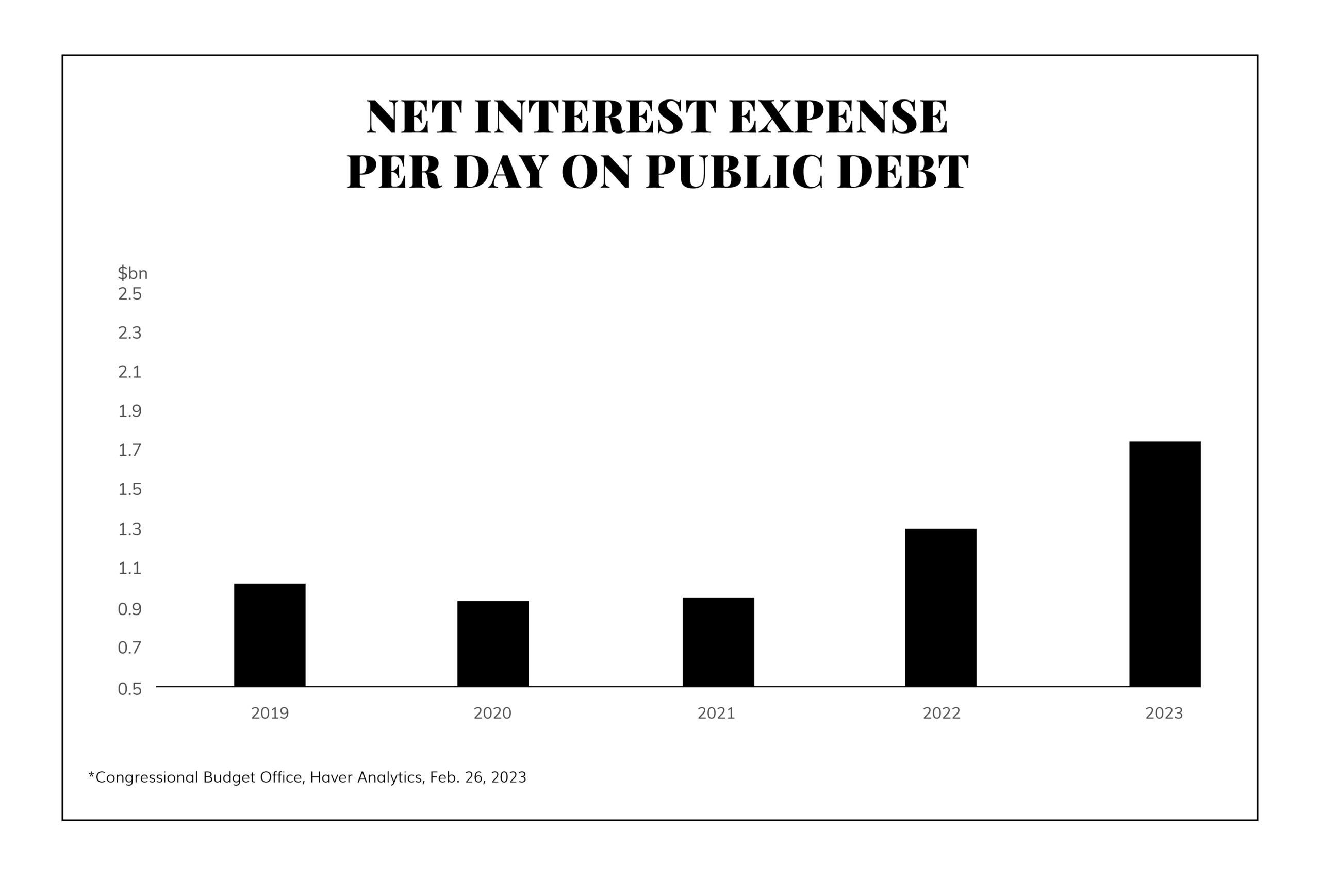

8% of our outlays go to mere interest payments on the debt (see Chart of the Week).

Everyone wants to reduce spending. No one knows where they ought to do it. And both parties have said “entitlement discussions” are off limits (the real meat of the national outlays).

I haven’t even started Dividend Cafe yet

None of the above are the heart of the cause of Japanification. That level of spending is entrenched in good times. The $31 trillion debt is the current number. The issue we have to think about as it pertains to Japanification is the future – what happens when we have a real recession, a real crisis, a real provocative event, etc.? In other words, my criticism need not be over the war spending of 2002-2006, or the GFC stimulus spending of 2009-2013, or even the COVID spending of 2020-2021, all of which I AM critical of. Rather, the real issue is the indebtedness in NON-crisis moments that serve as a baseline from which we can only get into serious trouble from. All of which serve as unsustainable numbers that strip away present and future growth and leave policymakers worse and worse options in the moments that the public is most screaming for intervention.

I can argue against Keynesian stimulus during crises (in fact, I do, for a variety of reasons). I can argue against a zero-bound interest rate policy during crises (in fact, I do, for a variety of reasons). But the real challenge we face is the spending we do outside of those moments and the lost efficacy of these [flawed] policy tools in real bad moments.

So where are we going from $31 trillion?

Tax collections are slowing down as the economy is slowing down. With or without a recession, revenues are not growing as projected by the Treasury.

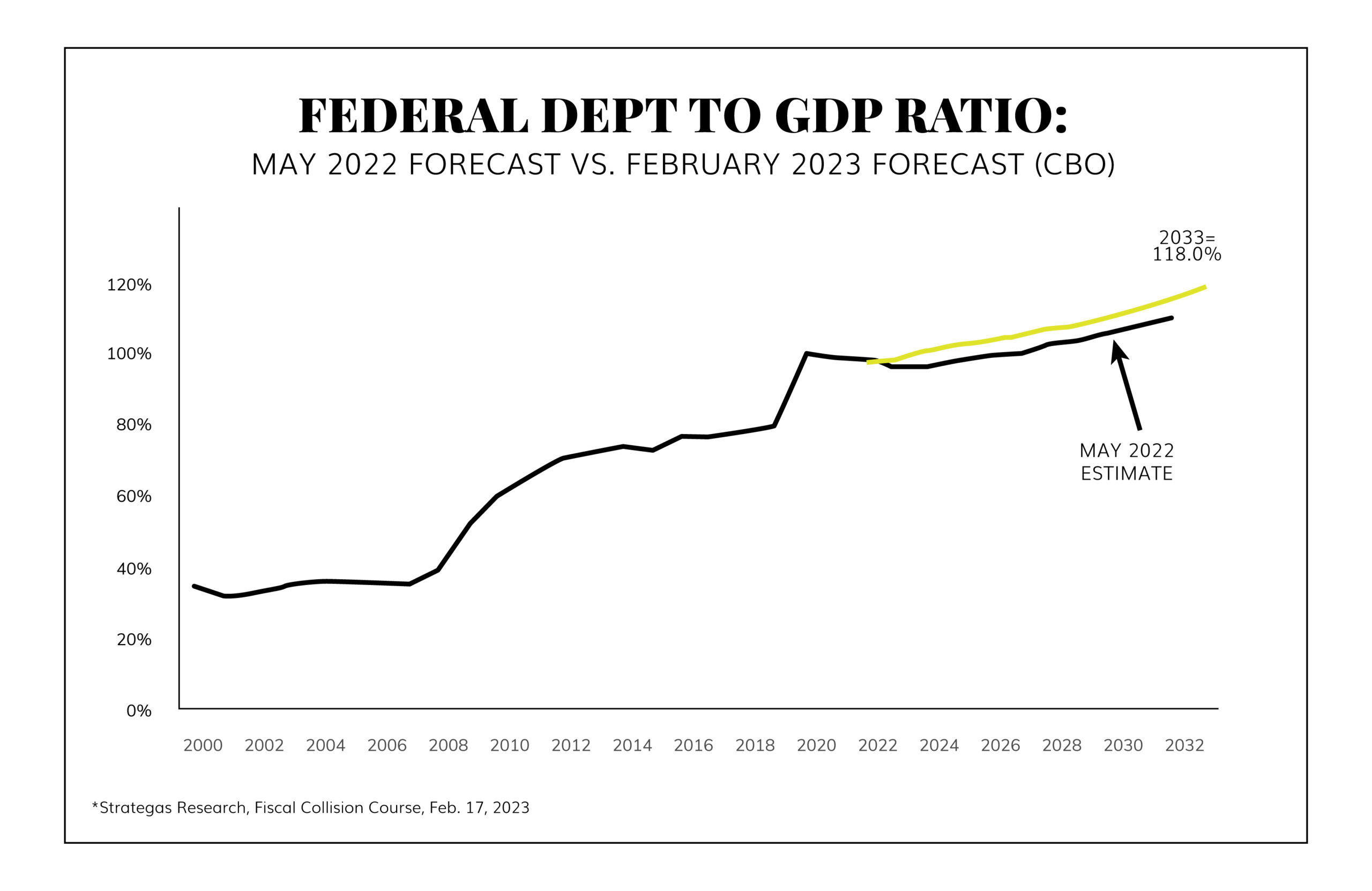

In the meantime, that 30-60% debt-to-GDP range we averaged from World War 2 until this new century is long gone, as is the 80-100% range we averaged from the financial crisis until COVID. We are now over 120%, and we are talking like that is permanent, baked in, and oh, that is if nothing bad happens.

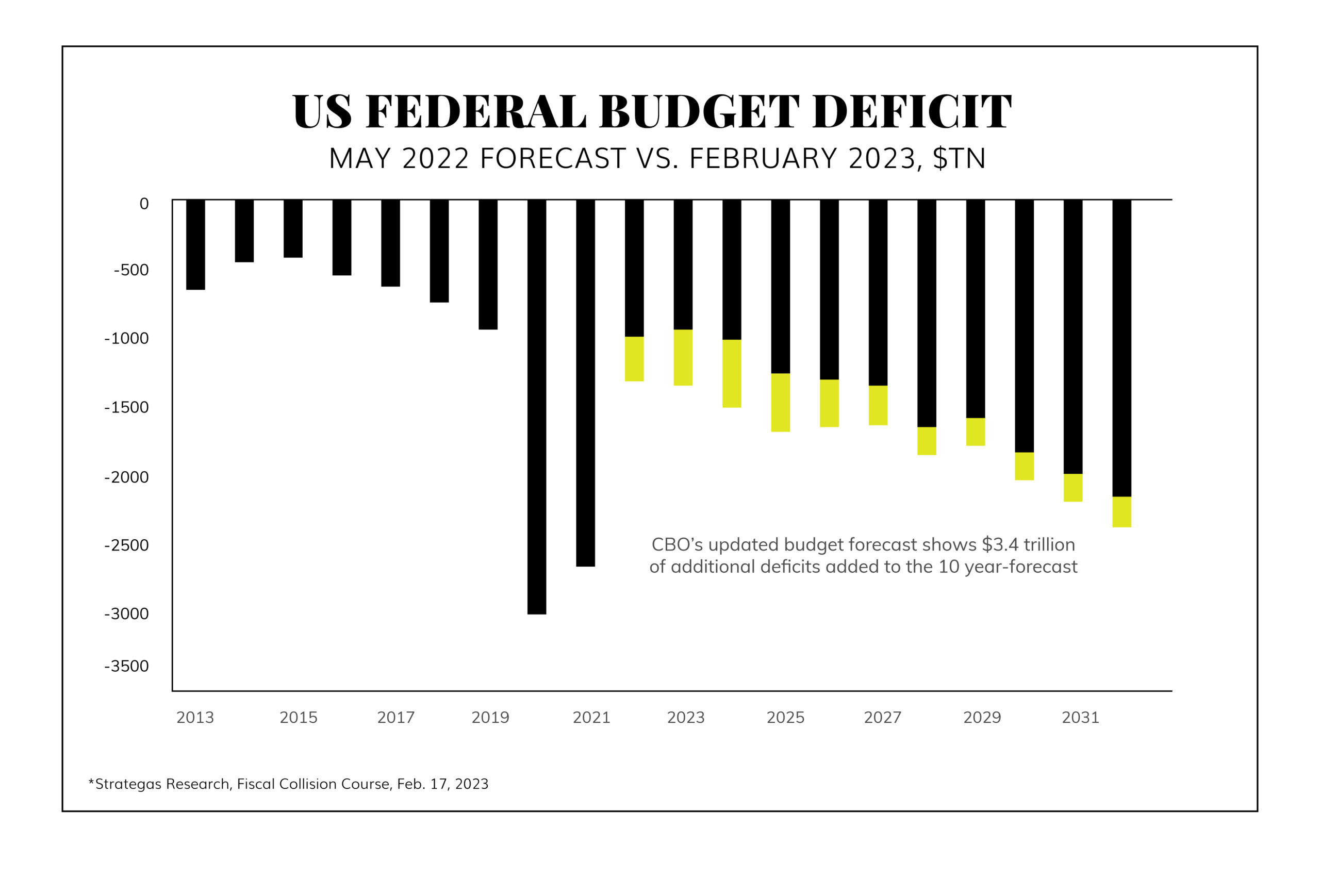

The spending is not going down. The deficits are not coming in. The only thing we are debating about is how much worse it gets and at what speed.

These numbers do not assume anything other than what we know. Interest costs could worsen. New spending packages could be passed. Revenues could decline more (they will decline more if there is a recession). You get the idea.

Well, actually, it can get worse

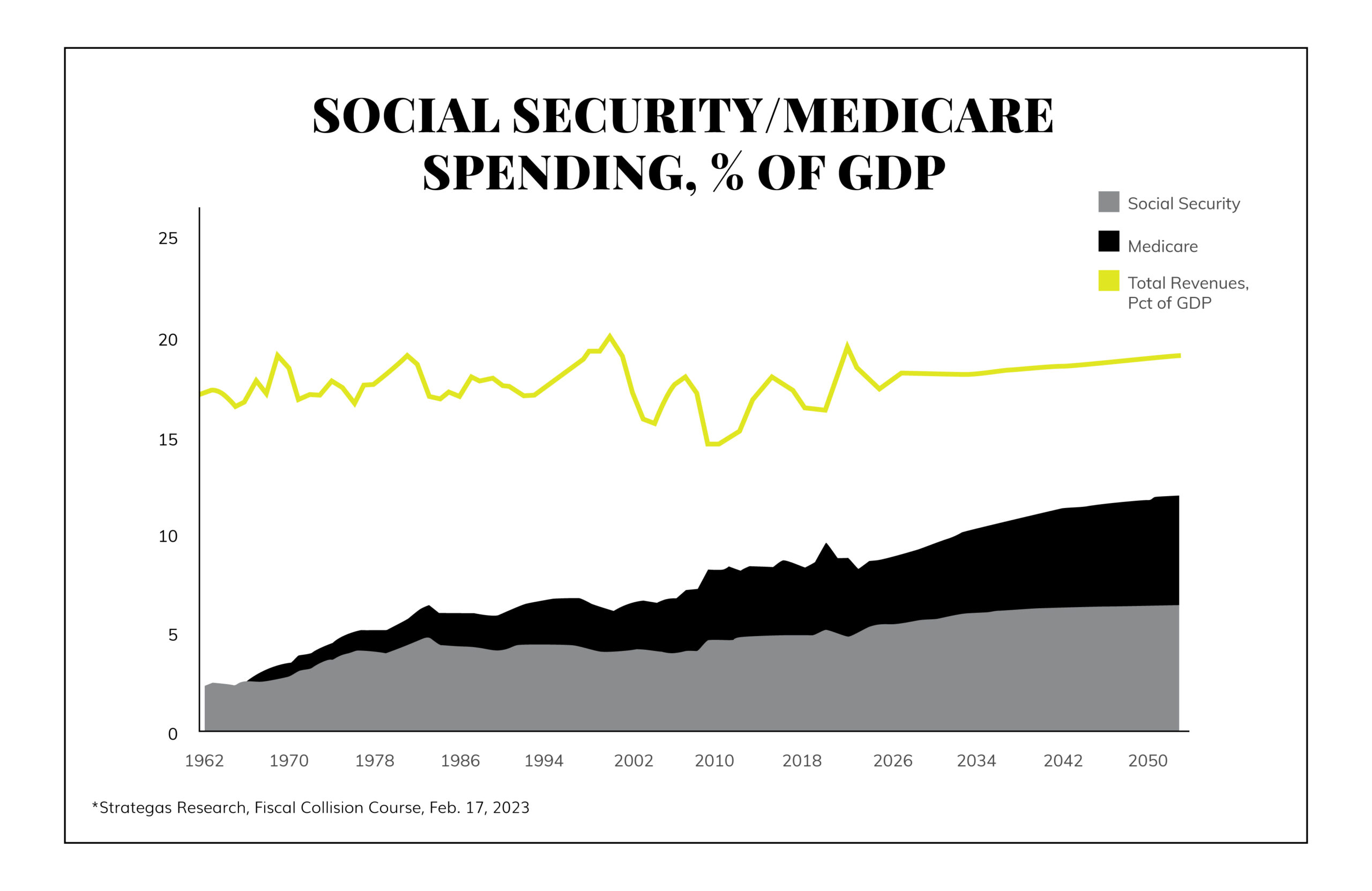

The unfunded liabilities of our Social Security and Medicare obligations are not factored in. The cost of these annual outlays is over 10% of the GDP, and they are committed to the people of the United States. Revenues into Treasury are the same percentage of GDP they have been for sixty years, but these expenses have tripled as a % of GDP. You get the idea.

Piling on, then I’m done

All of these numbers are FEDERAL debt obligations – national spending. They do not factor in states, counties, and cities. State tax revenues are now coming in softer than expected (after the boost of post-COVID re-opening and the huge COVID moment transfers from the federal government). Unfunded pension liabilities for states and municipalities are also above and beyond everything covered in this Dividend Cafe.

Sooooo ?????

There is no way to sugarcoat these numbers, and there is no way to pretend they don’t exist. There is room for debate about how much worse it could get, what should be done about it, or what parts of the cause were “worth it,” but there isn’t much debate about the fact that we have a current debt level that is massive, that most of it has come very quickly in the context of our own history, that annual budget deficits are adding to the debt number greatly, that this has been a very bipartisan issue in its causation, and that there is very little room in the reality of the present budget to do much about it.

So what happens next? A default? No, I very much doubt it. A societal collapse? That is a great thing to predict for book authors and subscription newsletter writers, but it hasn’t been a great call for those trying to do real economic projection and capital stewardship. Inflation? Hardly. Developed market history says the opposite. Political agreement on a rational and compromised plan to reduce debt? Now I am just toying with you.

I am left with only two conclusions about what happens from this point …

(1) Japanification, because it’s the only historical precedent we have – low/slow/no growth for an extended time, AND

(2) Surprises (that is, instability). Rates go higher than one thinks before going way lower than one thinks. The Fed enters a new market or enacts a new tool no one expects. Some shoe drops. Some shoe looks like it will, but it doesn’t.

Expect the unexpected.

Chart of the Week

We were spending $1 billion per day on the interest expense of our national debt before COVID. We are spending $2 billion per day now. The total debt did not double (though it went up a lot), but the interest rates did, and the short-term nature of our debt profile means the debt is getting rolled over into higher rates.

Quote of the Week

“Nothing is more responsible for the good old days than a bad memory.”

~ Franklin Pierce Adams

* * *

I will be in New York City through most of next week with a fun update to offer at the end of the week! In the meantime, reach out with questions, and they will be responded to! And, of course, welcome to the month of March, where by the end of the month, the federal government will have spent $1.5 trillion year-to-date … Yes, pretty soon, we are talking about real money, indeed.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet