Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I had a significant amount of research time this week, which led to a significant increase in subjects I want to cover in this week’s Dividend Cafe. I am confident you will find it to be worth your while to open this one, read it, and take it in. I am quite pleased with this week’s edition, mostly because as a writer, I love the dedicated focus I got to put into it this week (the eastern time zone always helps).

Yes, we cover the market action of the week (at least up until press time) this week. And yes, there are plenty of thoughts and ideas around the present investment environment … But I also think you will find this week’s Dividend Cafe to feature some longer-term reflections on the economy, on long-term challenges, on government debt, on corporate debt, and yes, on the interest rates that drive so much economic behavior.

So if you’re in the mood to get smarter this weekend, or to at least take in our best thoughts on these fascinating topics (I am not being at all sarcastic – if you can’t get excited about what drives world economies, that’s on you!) then jump on in to the Dividend Cafe!

Deja Vu in the Markets

Markets advanced significantly Monday and Wednesday this week, with a flat day (Tuesday) in between. As of press time, we are looking at a 150 point drop Thursday morning, so still a 250-300 point move higher on the week (thus far). There was not a particular or clear catalyst to market action this week, which makes things normal – in that markets rarely have a clear catalyst for why they advance or why they decline.

A funeral for Mr. Phillips

As the Phillips Curve continues its long-awaited funeral in the world of economics, the employment data continues to defy critics and pundits. Phillips Curve proponents have long held that an inherent tension exists between labor and inflation, that strong employment and wage conditions would create inflation and weak labor conditions would pull inflation down. The “curve” speaks to the alleged sweet spot at which inflation is not too hot, but employment not too cold. The theory is wrong because, well, it is wrong. Strong employment is not inherently inflationary (see: the last three years), and weak employment is not inherently deflationary (see: the 1970’s).

Last week’s jobs data saw 225,000 jobs created in January, nearly all in the private sector, and well above the 150,000 or so expected. The labor participation force growing to 63.4%, the highest in seven years, is by far the brightest note from the report. Wage growth at 3.1% continues to outpace expectations, put money in consumers’ pockets, and yet, not remotely indicate pending inflation.

There are those who fear that wage growth cuts into corporate profits, and a slowdown in corporate profits undermines the whole recovery. What has played out, and what many evaluating this miss, is that when wage growth is coming from higher growth, the impact of higher wages to profit margins is offset by that underlying growth, creating a pro-cyclical virtuous cycle. Mistaking higher wages for inflation is caused by a failure to appreciate the concept of productive growth.

Economics 101 – or 1.6%

How does an economy like ours have a ten-year bond yield at 1.6%? In what planet is a bank lending money to a homeowner for thirty years at 3-4% a good deal for the bank? In what planet is an investor lending money to the federal government for any period of time at just around 1.6% a good deal? In other words …

Why are interest rates so low ???

This requires a couple economic understandings that flow together. The answer is government debt, and it is highly contrary to conventional reasoning (to see government debt as causing rates to go lower, not higher).

What drives bond yields is inflation expectations. This is intuitive. The more one expects the purchasing power of their money to decline in the future, the more interest income they need to compensate for that erosion of value.

Velocity drives inflation expectations. The more the same dollar turns over in the economy, combined with more dollars in the economy, the higher inflation will be (Irving Fisher 101).

Over-indebtedness crushes velocity. The more debt in the economy, the less activity, the less money turning over (Irving Fisher 201).

High debt = low velocity = low inflation expectations = low bond yields

Ergo: Over-indebtedness leads to low bond yields …

The current budget deficits are pushing yields lower despite us being in a period of economic health. When, not if, economic conditions worsen, deficits will expand even more. And this is not just true of government debt but corporate debt, too. Each additional dollar in 2019 total debt added forty cents to GDP – but that number used to be fifty cents! And that marginal decrease in return on debt is even worse in Japan and the European Union.

So excessive debt creates diminishing returns (i.e. weaker growth) which combined with lower inflation expectations leads to collapsing bond yields.

When we understand this chain of events and causal interconnectedness, it allows us to better assess how to globally allocate capital and set expectations around these events.

A quick point about “growth” and “value”

Not a day goes by that I do not either hear someone say, or say myself, that the large decline in interest rates has already provided a big boost to bond prices, and that the major purpose in holding bonds now is far more defensive than offensive (yes, rates can drop further, and yes such deflationary risks warrant a fixed income allocation as a defensive hedge, but it would take an odd outlook to suggest that bonds are intended to be an offensive, premium money-making asset class in our portfolios this year). However, just as declining interest rates have been the mathematical driver of returns for bonds, declining rates have clearly fed the lion’s share of this monstrous run in what people oddly call “growth stocks.” The disintegrating comparable risk-free rate has re-rated and re-rated growth stocks over and over again to a higher valuation. So the question is: If one believes at this point the lion’s share of that decline in underlying interest rates is over, or mostly over, wouldn’t a down-tick in one’s exposure to an asset class that relies on continually declining rates make sense? Now, with bonds, as we just said, there is a defensive hedge objective in maintaining exposure. Do people own high P/E growth stocks for defense? I would think not (I would hope not).

I am the first to argue (including in this very Dividend Cafe) that low rates are here to stay. But rates that got low and stay there are different than rates that have gone low and are continuing to go lower and lower. Much of the so-called growth stock space seems to require continually declining rates. This changes the risk-reward paradigm a lot. Is it finally the “value” turn?

Did someone say value?

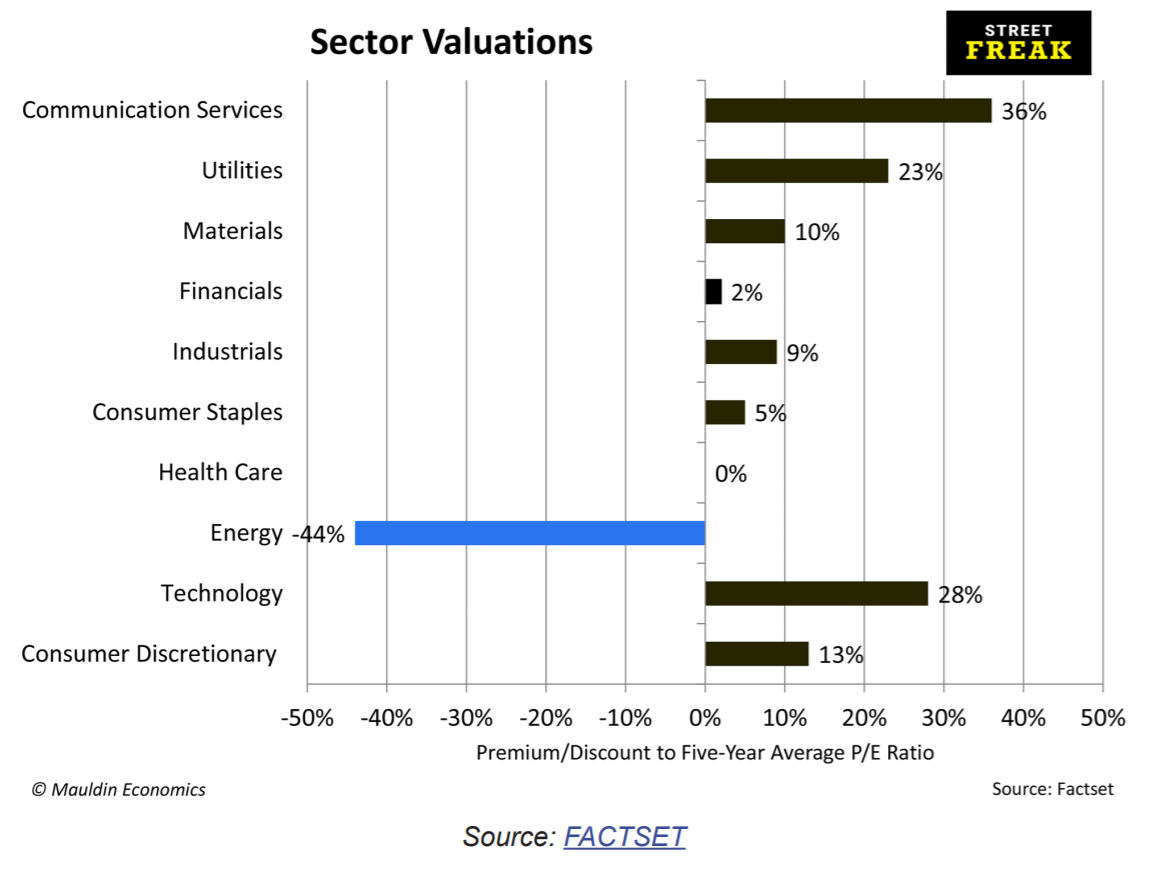

Those weeping and gnashing their teeth over the S&P 500’s P/E (price-to-earnings) ratio must surely be buying energy stocks with both hands, right? Indeed, if P/E averages are a sign of value (or lack thereof), what is cheaper in the invest-able universe than something trading 44% below it’s 5-year P/E average, and something that now makes up less than 5% of the total market index (a 40-year low)? Hate the energy sector or love it, but if this isn’t value …

A short term headline that matters

Earnings were expected to be down modestly in Q4 (consensus was for an earnings decline of -0.3%). Where we stand today is that earnings appear set to gave grown just over 2% on the quarter, and forward guidance looks quite strong as well (company expectations for their full 2020 results). Earnings were especially better in Utilities, Financials, and Health Care for Q4 (relative to expectations).

Party like it’s not 1999

There were a lot of analogies I made coming into 2019 out of 2018 that were parallel to how we entered 1999 coming out of 1998. As markets lived up to much of what I anticipated in the context of that analogy, some review of those parallels is in order based on how the 1999 story ultimately ended.

It is important to note that the Fed is continuing to support markets. That may or may not be a good thing, and it also may not be something that continues, but it is at least one categorical distinction. The Fed tightened substantially in 1999 (after big and inexplicable easing in 1998). Some tightening post-2019 equivalent to the 1999 tightening may very well come, but it is not yet.

Additionally, valuations were the highest in history as 1999 ended, and bond yields were higher. Today, valuations are lower, and even more importantly, the comparative risk-free rate is much, much lower.

Finally, the “retail” ownership of the stock market 20 years ago was a major catalyst to its fragility. This current bull market has been perpetually disbelieved by regular investors; that late-90’s bull market was the subject of Super Bowl ads … In other words, the hands were even weaker then that were holding it together.

My friend, Jason Trennert, of Strategas Research, also likes to point out that today’s Tech Sector, whatever one thinks about its valuation, is real – it is profitable – and it is filled with positive cash flows (contra 1999). And it is worth noting that 1999 saw oil prices explode to the upside which created significant economic distress as well. Fair points. But at the end of the day, there are ample differences between where we are now and where we were 20 years ago, and where there are similarities, dividend growth investors should feel grateful now just as they felt then.

A problem you see but so far away

One of the hardest things I face day in and day out is my belief that we face challenges in our corporate credit markets, yet believe those challenges may not surface for a long, long time. I see virtually no chance that they never surface, yet investing as if the challenges are imminent leaves money on the table our clients expect us to pick up. And yet, calculating risk/reward trade-offs is a big part of our job, and I see throughout the credit markets spreads that do not properly compensate investors for the risks they are taking. This “froth” can boil over in short order, or it can last for a long time.

Our solution has been to focus client bond portfolios on “bonds that act like bonds,” and to under-weight High Yield substantially. Other credit asset classes may be exposed to the same dynamic, but we prefer approaches that emphasize bottom-up underwriting diligence (i.e. private credit, middle market lending, etc.). We do not expect spreads to stay this tight forever, and we do not want them to. But investors buying entire indexes or funds are making a bet on a macro spread tightening, and taking a risk they do not know they are taking, and are not getting paid well to take.

Not just wonky economics any more

Long-time readers know that I very much believe that the Federal Reserve is headed towards some form of monetization of the U.S. debt (with the debate over the degree and obviousness of it more than anything else). This is not a conspiratorial view; it is not a doomsday view, it is not a pollyannish view, it is just what it is – a mathematical view.

And yet it is also not particularly helpful to investors to know that this is where we are headed (markets intuitively know it anyways), because the details matter. When. How much. How. In what way. There is not enough specificity in saying “monetization” to draw actionable conclusions.

What the Fed says about its continued money operations at the short end of the curve in the months ahead will tell us a lot about their candor and intentions. A “few months” of technical bond-buying (“non-QE, QE”) to offset some of the irregularities in the repo market and liquidity issues in the banking system is one thing; a perpetual and seemingly permanent intervention in such will serve as a huge signal to Fed watchers about what inning of the monetization exercise we are really in.

Right said Fed

Let me summarize two things I want my clients and readers to understand about our view of the Federal Reserve’s present posture: They currently have a balance sheet of assets in excess of $4 trillion. They had reduced that balance sheet down to below $3.8 trillion, and yet since last September have added $350 billion and counting to it. Why is the balance sheet being added to rather than subtracted from? Unemployment is at historical lows. GDP growth is fine. Economic conditions are good if not great. Why are we seeing monetary actions that you expect in the midst of a crisis?

The answer is two-fold. (1) The patient is addicted to liquidity, and the Fed takes seriously to give their patient what it needs. (2) The debt needs of the United States are severe, and the Fed takes seriously their responsibility to keep that debt wheel turning.

Is this wrong? Should the Fed be doing differently? I am not saying that, though I am not saying the opposite either. What I am saying is that a better discussion of what the Fed should do, and what the Fed will do, and more importantly, what we should and will do, can all take place once we have an understanding of what the Fed is doing, and why.

The Fed has some crisis-level monetary actions going on right now, and we are all acting normal. The economy loves free-flowing credit. The government loves low-cost unlimited debt-issuance. Both things require a cooperative central bank. And a cooperative central bank we have. Boy, do we ever.

A bull market reminder

The present equity experience (shaking off coronavirus, expanding multiples in already-rich tech sector, poor reception to competing asset classes, etc.) has all the ingredients necessary for real complacency to sink in. Ironically, there is a vast amount of investors who, rather than being complacent about standard market risk, have missed the bull run all together. But for those who are properly allocated, have not allowed greed or fear or major financial mistakes to starve their outcome, an important reminder should be maintained in the pages of Dividend Cafe until kingdom come … Bull markets come with volatility, too. The shake-up in late January will not be the last period of fluctuation before this bull market ends … And as this chart reminds us – it wasn’t the first either – not by a long shot!

Politics & Money: Beltway Bulls and Bears

- The New Hampshire primary did not necessarily do a lot to clear up where the Democratic Primary is headed, as the following things happened:

- Yes, Bernie Sanders won, but by a far smaller margin than had been anticipated.

- Mayor Pete Buttigieg came in a close second, and combined with his close first finish in Iowa is the overall leader in delegates after the first two states, and has a high momentum going into South Carolina and Nevada.

- Amy Klobuchar had a strong third place finish, picking up over 10 points from where the polls had her just days before the primary … Whether or not she has the money and infrastructure to parlay this strong third place finish into better momentum in future states remains to be seen.

- It seems laughable to think Elizabeth Warren or Joe Biden can continue after their disastrous showing in both Iowa and New Hampshire, but they may very well wait through a few more states for more humiliations to confirm this.

- Michael Bloomberg’s path continues to be the hope that he will perform so well on Super Tuesday that the delegate count gets fuzzy. The idea of not having a nominee until the convention is increasingly possible, if not likely. But Bloomberg’s path benefits from the fall-off of Joe Biden, but is challenged by the strong showing of Klobuchar and Buttigieg.

- The division within the pool of Democratic candidates seems to be intensifying, and it will be interesting to see what distinctions candidates are willing to draw between themselves and others in the days and weeks ahead

- The Federal Trade Commission announced it is investing a handful of big tech M&A deals done over the last decade, for reasons unbeknownst to me.

Chart of the Week

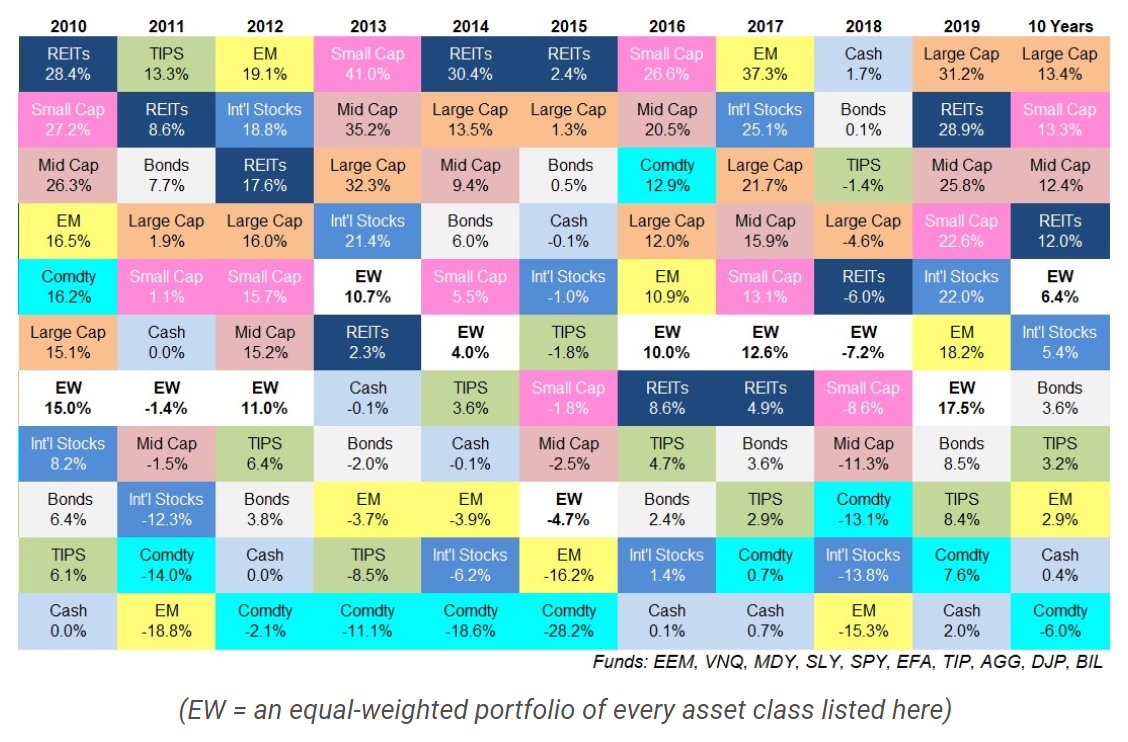

Just a friendly reminder on why we asset allocate at The Bahnsen Group (and why good investors everywhere do the same) …

* A Wealth of Common Sense, Ben Carlson, Jan. 16, 2020

Quote of the Week

“The only permanent wealth is what you carry around in your head.”

~ Felix Rohatyn

* * *

I really did enjoy writing this week’s Dividend Cafe, and I hope you got a lot out of it. I understand some of these topics may warrant additional questions, and I welcome any such inquiries that may be on your mind.

We do not believe the headlines of the week will drive long-term investor outcomes. The short-term noise that captures 90-99% of investor attention, and certainly media attention, is among the least relevant in understanding what will drive actual financial success (or lack thereof). Broader, more structural economic considerations matter a great deal, though. How investors behave through noise (ignoring it) matters, and how investors are positioned around great structural themes (wisely) will also matter a great deal.

Those two arenas are what we do at The Bahnsen Group. Behaviorally guiding our clients through the things that don’t matter and intelligently allocating client capital through the macro things that do matter. To these ends, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet