Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Bring up the issue of “off-shoring” American manufacturing, and you will get a wide variety of responses, many of them highly emotional. Today’s vernacular talks about “on-shoring,” “re-shoring,” or “near-shoring” – various synonyms or adjacent concepts to the idea of reversing certain trends of globalization, primarily the ones dealing with American activities in manufacturing and the supply chain.

As is the case with almost every topic I could ever address these days, the subject is complex, requires nuance, and doesn’t come close to one of the two simplistic boxes we are supposed to fit all of our thinking and analysis into. My interest in this Dividend Cafe is less political and more economic. It is less about making a statement and more about doing some analysis. It is less about finding a campaign message and more about finding an investment thesis.

So to those ends, we work. Let’s talk about expectations for America’s supply chain management in the years ahead.

|

Subscribe on |

From left to right

For years opposition to “off-shoring” was more associated with the political left, as candidates like Mitt Romney were hammered for past business activity that allegedly moved some jobs offshore. For the last eight years, a more economically nationalist message has been part of the populist right, with the 2015/16 Trump campaign popularizing the idea that free trade and offshore manufacturing were a problem for U.S. workers, particularly in the Rust Belt and other states with heavy blue-collar worker populations.

What began as a pretty basic protectionist message (not too different from past screeds from the likes of Pat Buchanan and Ross Perot) has evolved over the last eight years. Various human rights issues were juxtaposed into the protectionist rhetoric about offshore manufacturing, and then post-COVID, a layer of national security was added to the mix.

What began as a sort of pandering message that “all the lost jobs in Ohio are coming back” has now become a more legitimate question about America’s dependency on Communist China for our supply chain. It has generated a lot of heat, some intelligent commentary, and some, well, not intelligent commentary. But the issue is not only front and center politically but also sits at the crux of one of the most potentially impactful arenas of our economic life this decade.

The partisanship of this issue is more grey than red or blue. I can’t imagine a major party candidate running right now as “pro-China,” and it is worth noting that not a single tariff of the trade administration has been repealed since the Biden administration took office. This is not to say they were good or they were bad (I assure you I have my opinions) – it is merely to point out that maybe the Biden administration proved to have more similar opinions on this matter to the Trump administration than some would have expected. Or, maybe, it is a reflection of the understanding of the American mood here …

The COVID pivot

I am not a protectionist, and I do believe in the Ricardo law of comparative advantage. For those who have not taken my free economics course (LOL), I refer to the great classical economist, David Ricardo, who theorized that nations gained an advantage by producing themselves that which had the lowest opportunity cost relative to other goods that could be produced elsewhere. Each nation trading with one another based on where they can do a certain thing more efficiently than another nation can create a global advantage in trade optimization and economic results.

Where a more serious pivot against the global trade, manufacturing, and supply chain dynamic of the last 20 years took hold was not in the protectionist moment of 2016 but rather in the aftermath of COVID. A more penetrating skepticism of the CCP in China had taken hold in the U.S. on a reasonably bipartisan basis, and the lockdowns of the COVID moment caused many Americans to realize that China’s role in the supply chain that is necessary to get finished products to the United States was more serious and vital than previously understood. This had ramifications for things like medicines and pharmaceuticals, but also cleaning supplies and other household products, and perhaps most importantly, semiconductors.

Out of the 2020-2022 moment, a heavy conversation has taken place on whether or not much of the offshoring that has taken place to China for various manufacturing needs should be rethought. Unlike the 2015-2019 moment, much of this conversation is not so much protectionist (i.e., “a company should damage itself and its customers for the sake of offering the job at a higher cost and regulatory burden and worse outcome to a U.S. citizen if they can find one who wants the job”) – but rather centered around concerns of national stability and security in the pragmatic realities we uncovered throughout COVID.

Culture war and economics always intersect

If all we were talking about was China’s record on human rights, with no economic or national security implications, perhaps this would be different. And if all we were talking about was that economic stability concern, with no cultural or broader values discussion, perhaps it would be different. But what has happened is that various concerns on one side of this continuum have supported the concerns on the other side, so a sort of coalitional movement to “do something” or “change something” has formed, even if not always motivated by the exact same thing. For my purposes, there is still a little too much potpourri and not enough focus in organizing the thought and argument, but that potpourri, even if sometimes incoherent intellectually, is where the energy behind this directional change gets its force. And here we are.

It pays to be friends

A stronger fraternal relationship (whether such a thing was morally justified or not) would alter a lot of the national conversation and policy intentions. It was not my understanding that Saudi Arabia was a boy scout for most of the last 70 years when the U.S. had a strong fraternal relationship with them, but sometimes various shared objectives help accommodate peculiar alliances in the diplomatic stage. That has been true with China for some time as well, for good or for bad, but has clearly changed in recent years.

So is this really happening?

45% of companies in the American Chamber of Commerce in China say China is in their top three countries for investment, down from 60% just two years ago.

China has taken active (and massive) steps to partner with Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries for their oil and gas needs and sought to bypass petro-dollar payments by purchasing in Yuan-denominated transactions.

The U.S. has not merely used export controls of its own with China (for example, banning or severely restricting advanced chip manufacturing to China), but it has secured agreements from other European and Asian countries to do the same.

In 2020 the number was 15% of American companies manufacturing in China said they were considering or taking active steps to relocate some manufacturing outside of China. That number was 24% last year and will surely be higher this year.

China’s cost competitiveness itself (the whole thesis in that manufacturing comparative advantage) has largely dissipated, as labor is now cheaper in many other countries (Mexico, and other southeast Asian nations) than it is in China itself.

Imports from China into the U.S. as a percentage of total imports have dropped to their lowest level since 2005 (down from 20.3% seven years ago to just 13.4% now)

Changing of the guard

Gone is the talk of using tariffs to “even the trade playing field” (i.e., get China to buy more from us). Now, the objective really is to simply use China less in American supply chain needs. Export controls and investment restrictions are meant to significantly alter the ratio and leave it altered, not motivate a re-negotiation where buying and selling get to parity. The conversation changed, the reasons for that changed, and now, the policies coming with it have changed.

This could impact your teenage daughter!

If all we were talking about was potential privacy and data security issues with things like TikTok, I would not dedicate a Dividend Cafe to it. Yes, stuff like TikTok and app-based ramifications on privacy and security are likely to continue getting headlines, hearings, and attention, but the investment implications of a broad change in U.S. use of China for manufacturing needs are much bigger than TikTok.

Rare but unsafe

One of the most discussed concerns in terms of China’s leverage over the U.S., if we were to alter the playing field too dramatically, is the dependency the U.S. has on China for rare earth minerals necessary (and I should point out Europe as well, which currently gets 98% of its rare earth mineral needs from China). There is plenty of talk of the U.S. capacity to meet its mineral needs domestically, but it is unclear if the U.S. is willing to do so, what that capacity really is, and what the environmental comfort level is with taking this decoupling step.

The hard facts

The reality is that China is the largest trading partner for most of the world, not just the United States. Only about seven countries of the world’s largest forty countries receive more imports from another country than China. In 2002 there was ONE country that received most of its imports from China. In twenty years, that list moved almost entirely to China.

There has certainly been more bark than bite in all of this so far. Yes, the Biden administration restricted new investment in China, but only on new investments, and they delayed the start date of the restrictions. Furthermore, the restrictions did not touch Energy or Biotech/health care – only technology. No one is under any impression that this is all going to be easy and smooth.

Nevertheless

My macro outlook is quite simple:

(1) Whether or not one agrees with why it is happening, or how it is happening, or should be happening, there is a change underway in the America-China economic relationship that will alter U.S. reliance on manufacturing in China and “onshore” or “near-shore” more and more of the U.S. supply chain activity in the years ahead.

(2) This will present challenges in the cost structure for multi-nationals (for a period), and the volatility potential retaliation from China represents.

(3) This will present opportunities as desperately needed capital expenditures come back to the U.S. and potentially allow for a boost to productivity and other peripheral economic benefits.

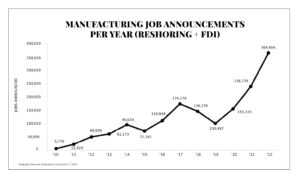

Factory construction is rising, and I believe it will continue to. Spending on such is up a stunning +77% over the last twelve months, and as factories are built, next comes the machinery needed to fill them and then the laborers needed to work in them. This is a boost that may be a very under-appreciated catalyst for economic activity in the years ahead.

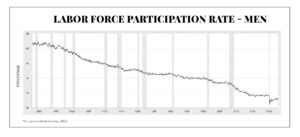

All of this also depends on a major concern in the chicken-or-egg debate of it all: Will we have the labor force needed to meet the moment? If we need factory investment and capex and onshoring to get the labor force back, great – it should all come together. But if we need the labor force to get the capex and manufacturing investment back, Houston, we may have a problem.

Investment outlook

(1) There is no point coming, none, where a simple, clean, quiet, undramatic break from the heavy economic connectivity with China takes place. The pain points are too sensitive for there not to be various escalations and tensions along the way that enhance global volatility, particularly for multi-nationals.

(2) Yet, betting on “who will be punished most” in a re-working of the U.S.-China economic relationship ahead is not so easy when carve-outs, exceptions, incentives, and special deals have historically been the norm, not the exception. One company or sector can look like they will take it on the chin in changing conditions with China and yet, underneath the surface, be exempted altogether. It is the nature of the beast in this cronyist age.

(3) On the surface, the passage of the CHIPS Act last year looked like a boondoggle opportunity for American semiconductor companies, but the strings attached to getting the manufacturing subsidies and tax credits may neuter its efficacy. The semiconductor space is hard enough to invest in without guessing who will benefit from corporate welfare and who will not. Investment decisions are best made here where there is less reliance on crony support and where there is less revenue exposure and supplier exposure to China. $200 billion of projects for U.S. chip manufacturing are underway now, a number projected to grow to $350 billion, and 35,000 jobs should come with this investment. But I would focus more on the macro than the micro here – the broad economic impact is more digestible than speculating on which companies benefit (and which suffer). In fact, the companies doing the greatest investment in onshoring chip manufacturing have performed the worst thus far!

(4) Industrials and Materials ought to benefit from the increased capex thesis surrounding greater investment in U.S. manufacturing. Demand will need to increase to meet the growing capacity, and demand is limited by downward pressure on economic growth, but enhanced capacity is a solid way to start. Efficiencies will need to be improved, and there will be successes and failures along the way. This is not a “buy them all” easy call. Selection and execution will matter. And it is entirely possible large capital investment in this next phase stalls and slows until the Fed tightening cycle ends. There is no timing mechanism in any of the theses I am describing.

(5) Government subsidies and interventions will not make it more attractive but rather more convoluted. Picking winners and losers will distort price discovery and alter incentives. We should not run to government largesse as an investment strategy but rather away from it.

(6) Uncertainty over what China may do with Taiwan and what the U.S. would do (or need to do) to protect Taiwan adds a layer of support for the U.S. defense industry. China themselves has increased its own military budget by +7.2% over the last year, and the U.S. is not likely to go the other direction with this “lukewarm potato” out there.

Chart of the Week

Few charts ought to spark more cultural, economic, and, dare I say, theological debate than this one …

Quote of the Week

“Gold rushes tend to encourage impetuous investments. A fee will pay off, but when the frenzy is behind us we will look back incredulously at the wreckage of failed ventures and wonder, who funded these companies, and what was going on in their minds?”

~ Bill Gates

* * * * *

I hope this was as informative and useful as I intended it to be. There is a tendency with macro thematic considerations to want an easy takeaway – a “can’t lose” investment pick that flows from it. The subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe does not come with one. It is nuanced and complex – there is a potentially good thing unfolding in the macro sense for the U.S. economy – that has potentially risky side effects and ramifications along the way. There is an investment opportunity that may play out, with risks and uncertain timing to accompany it. All of this is true at once. And prudent investors know it was never meant to be easy or simple.

Enjoy your weekends. And maintain the dividend growth mentality.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet