Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Any time I use some sort of sports analogy in the Dividend Cafe I get a lot of emails from people who connect to it and say they love it, and then I get emails saying, “come on, I don’t care about sports – please just stick to the market!” I am never offended or bothered – Abraham Lincoln had a line about pleasing people once – but I am also not swayed. If I think there is a real investment or economic lesson that can be told with a sports analogy, I am going to mix that chocolate and peanut butter. And I promise you, today’s broad takeaway for investors is worth it even for your tortured souls who hate sports.

So jump on in to the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

March Madness like no other

I basically have two loves when it comes to sports: USC football, and March Madness. I wish I had more time for sports watching than I do but USC football and March Madness are the two events that, even as a workaholic/father/husband, I still love.

USC football is an obsession, a passion, and a true love, inextricably linked to my late father, my childhood, and an underlying mantra (Fight on!) that most people walking through life dedicated to boring mediocrity could never appreciate … But I digress.

My other sports love is March Madness – the glorious period in college basketball from mid-March through the first Monday of April where dreams are realized, hopes are dashed, bets are made, buzzers are beaten, and yes, brackets are busted. No event in sports allows for so much drama, so much fun, and so much aspiration – and over such an extended period of time.

Bracket Busting Nightmares

As I mentioned, one of the real joys associated with the tournament every year is bracket mania, where even people who have never watched a college basketball game can make a bracket of the 64-team tournament and compete for bragging rights (or, ummm, a prize). Upsets make it very hard for everyone, and the mere act of tracking one’s own bracket gives a little “buy-in” to everyone – even the sports haters of society.

Well, it helps to know a lot about college basketball, right? To have a certain theme in mind that one can apply to their bracket selection. Nail the themes then nail the bracket – seems so simple! “This is [fill in the blank]’s year” means that if you filled in the blank correctly you should do well. There are any number of opinions, strategies, or themes that one may forecast, and if done correctly, set themselves up for bracket glory.

This year I made several bold proclamations early and often. “The #1 seeds are irrelevant this year,” I boldly proclaimed. “There is way too much parity and in come cases a #1 seed and a #5 seed are one and the same.” Pretty smart, right? Well, we didn’t have a single #1 seed who even made it of the Sweet Sixteen (consider it the octo-finals). “There will be more upsets than we have ever seen this year,” I said. #15 Princeton beat #2 Arizona. #16 Farleigh Dickinson beat #1 Purdue (yep). #13 Furman beat #4 Virgina. #8 Arkansas beat #1 Kansas. It could not have been a more “disrupted” first couple rounds of the tournament. “Anyone can beat anyone and once you get to the final sixteen teams all bets are off,” I declared, contradicting the conventional wisdom that the top teams who make it to the final rounds are most likely to end in the championship game. By the end of the weekend, tournament favorites Alabama, Houston, Texas, and UCLA were all gone.

In short, I was brilliant. I made all the right macro calls. I went out on a limb and defied conventional wisdom. It was me at my finest as a prognosticator of college basketball.

And here is my result in my bracket pool, #53 out of 63 contestants.

![]()

Yep, 53rd place. Now look, it isn’t like I was Brian Tong or Lukas Klause of the TBG Content Department, who are #61 and #63, respectively, or TBG partner, Trevor Cummings, who is #62. Now that would really be humiliating, right? But how in the world can one make all the right macro calls and still end up in the bottom of the bracket?

Because like in investing, there is a multi-variant explanation for results. And like in investing, all sorts of things can go wrong.

For you non-bracketologists

One does not need to have the March Madness bracket experience to know what it is like to get so much right, only to get so much wrong.

Consider the things that happen in election cycles all the time, where variable A goes exactly how some predict, but some other variable B changes the outcome. Did those who predicted President Trump would repel many independents and moderates in 2016 get it right? Sure. Did they miss the volume of blue-collar voters in rust belt states that would be “just enough” to get him over that electoral college edge? Yep. Polls indicate things that veer another direction. A finger in the wind from what donors are doing can often conflict with what voters do. I could go on and on – anyone who has spent any time interested in politics has experienced getting some inputs right only to get the outcome wrong.

Even in the world of economics and markets, I think of the years leading up to the financial crisis. I cannot even fathom how many times I said in 2004, 2005, and 2006 that housing was in a grotesque bubble that would not end well. Turns out, I was right. But did I know of the leveraged exposure to CDOs (collateralized debt obligations) on the balance sheets of our largest financial institutions? Did I know the complexity of the counter-party exposure via swaps and derivatives that would bring Wall Street to its knees? Did I know that a correction in housing prices would sink employment and consumer demand (i.e. access to credit) to levels not seen since the Great Depression? Sometimes you can be right with a premise and get a conclusion wrong. And sometimes, you can get a premise and conclusion both right but miss an adjacent conclusion entirely, to the point of negating the part you did get right.

The crypto space screamed from the heavens in 2021 and 2022 that central banks were unreliable (they were) and currencies were unstable (they were). They called for a defense against inflation (prices rose). And through all the accuracy came … a -70% implosion.

I can go on and on, but I trust you get the idea. If you want more examples, please be clear in your request if you want sports analogies or investment cases.

Why?

Why do things work this way? Part of me is tempted to appeal to Proverbs 16. I think we all think and plan a lot of things, and God sort of does what He does. But beyond the obvious spiritual reality of it all, some of it is actually quite scientific and certainly coherent metaphysically: Multi-causal and multi-variant facts and patterns are really, really hard to predict outcomes from.

Some basic market reality

When it comes to the analogy I am making to investing, allow me to lay out a simple case as it pertains to “macro” events and the market and particular investing around it.

- Macro is impossible to nail.

- Market reaction to macro is truly impossible to nail.

- Therefore, #1 makes basing portfolio decisions on macro questionable, and #2 makes it a really stupid idea.

What we have in today’s investing world is a whole bunch of people who sometimes get the macro right (as I did with my assessment of the college basketball tournament this year), often get it wrong (as I usually do), and whether right or wrong, have no repeatable way to translate that view of the macro into a repeatedly successful investment strategy.

I will add, I do not mean that “getting macro right does not assure you of a market call” – I mean, literally, actually, seriously, that it does nothing to translate to a successful market call.

I remember in 2008 hearing a guy who I will not name because he likes to sue everyone who says bad things about him go on TV all the time to say, “the market is going to crash,” and the “world is in a credit bubble.” It was exhausting, but hey, the market crashed and the world was in a credit bubble. A few months later, I was reviewing the account statements of a client of this person and was shocked to see that they were down -50% or -60% in their portfolio. This individual had the macro right and executed upon it by investing in something else that got hit just as hard, if not worse. There you go.

No one benefits from predicting a hurricane only to have a tornado destroy your house.

This is one of the most comical things about following the perma-bears of the world. They are almost always wrong about the macro, and then in those broken-clock moments where they are right, they still don’t make any money. It is mostly sad, but also kind of funny. Okay, it is super funny. But not as funny as my bracket.

For my next trick?

Macro “calls” in the market suffer from another problem, too. The next day. The next week. The next month. The next year. You get the idea.

One of the most famous hedge funders in the world made billions for himself and his clients in 2008 by shorting housing. Since then, he went really into gold, lost a fortune. He went really into Valeant, lost a fortune. He went really into [I can’t say the next thing or it will give it away who it is], lost a fortune. But hey, he is a billionaire from shorting housing. Lesson: He made money once. Lesson #2: Investors with him have not made money since.

Macro calls are hard. Making money on them is harder. Doing it again and again and again is really, really, really hard.

Next year I will not be advantaged in my bracket by having called the macro right this year. In fact, next year, I will be vulnerable again to both my macro calls, and the execution thereafter. Multi-variant risk. Good times. Go Duke? Sheesh.

Conclusion

A coherent investment philosophy that is rooted in real economic theory, that accounts for the macro – even the macro one gets wrong, and is not dependent on execution luck from a macro thesis, is all available for those who want it. Ours is called dividend growth investing, and we can defend it epistemologically, historically, theologically, economically, mathematically, mechanically, and any other way you want us to. But what we can’t do is say that it works because we can call the market, or call the macro that we think will drive the market. We can do no such thing.

And apparently, even if we could, we might get 53rd place in the March Madness bracket.

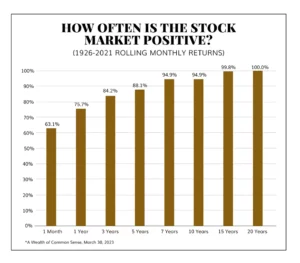

Chart of the Week

I think lessons like this are always worthwhile. History over macro.

Quote of the Week

“Perhaps, indeed, there is opportunity. Maybe there is that treasure on the floor of the Red Sea. A rich history provides proof, however, as often or more often, there is only delusion and self-delusion.”

~ John Kenneth Galbraith

* * *

May the Final Four this Saturday and the championship game Monday night be as exciting as the first four rounds were. And may markets consider a little less excitement than they have had (stock and bonds at high volatility even though there has been good movement as of late). But whatever happens, may analysis be prudent, execution be careful, and may humility guide all we do. To those ends, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet