Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I appreciated the very kind words I received about last week’s lengthy Dividend Cafe, and hope the message coming out of that annual week of meetings was clear and useful for readers. I struggled with where to take Dividend Cafe this week as last week’s covered so many topics, the Fed’s announcement this week was no real surprise at all, and I desire to write less about the Fed in the Dividend Cafe. On that last part, it isn’t going to happen – and that’s not merely because of my not-so-secret obsession with monetary economics. I may believe (and I assure you, I do) that the Fed policy framework of this era has given a way higher role to the Fed in modern economics than is appropriate, but believing it shouldn’t be is different than believing it isn’t such. So yes, the Fed is going to be a heavy theme in Dividend Cafe for years to come (whether I like it or not).

But if there is one thing I am obsessed about more than monetary economics, it is dividend-growth investing. And I think you will find some observations about dividend equity investing to be very relevant to the paradigm in which we find ourselves.

So today is not quite Fed-free, but it is rich in dividends, the very rewards I want for investing clients. Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

Setting the Comparative Table

I have invested client capital professionally for over 20 years, and have been intellectually and ideologically committed to dividend growth for 15 years. Note the federal funds rate throughout this period of time:

*St. Louis Fed, Economic Research, Federal Funds Effective Rate

The 10-year bond yield is currently 4.1%, almost double the yield it has averaged since the Great Financial Crisis.

*St. Louis Fed, Economic Research, 10-Year Treasury Yield since 2000

The S&P’s dividend yield remains below 2%, only sitting between 2 and 3% for the brief period of 2008 when S&P prices collapsed, and from 1992-1995 before the big tech boom began.

*Nasdaq Data Link, S&P 500 Dividend Yield since 1990

In other words, for most of my investing career, I have been investing around a mantra of high and growing dividend yield, in a period where the dividend yield of the S&P 500 has been right around 2%.

This Orange is Better than that Apple

I have frequently made the argument that dividend income for a new investor to our dividend growth portfolio (whether they need that income or reinvested it) would be double that of the S&P 500, and double that of the 10-year bond yield, with substantial growth of that income to follow year-over-year. One could (and should) deduce that some form of price compounding would be expected to follow, in the sense that underlying assets or worth the net present value of their future cash flows, so if those future cash flows are growing, the intrinsic value is growing as well. But that price appreciation is an effect of income growth, not the cause of our interest, and I hate confusing cause and effect when it comes to investing. But I digress … The notion of a starting point of higher yield combined with growing income versus flat income was a compelling case for dividend growth (versus both the S&P and the bond market).

But what about this Orange and that Banana?

A fair question now is whether or not this holds up with the 10-year now at 4.1% and the S&P up from 1.3% to 1.9%. Well, I think I have written enough in the last few weeks about the structural flaws of the index. That the index has dropped over -20% and the yield is still less than 2% is not good. It both speaks to potential downside risk from here, and the cause of this last bear market for the S&P (that is, that the index was so expensive that the yield was 1.3% and that the dividend commitments of the underlying constituents adjusted for weighting are so paltry and nominal, now, in the current environment). So I will leave the S&P comparison to go and start with the question:

If our dividend growth portfolio has a current yield of just over 4%, and the 10-year treasury has a yield of just over 4%, is there really a reason to endure equity volatility?

Recognition where due

And first comes the part of my answer that will surprise you: A starting point of 4% in the bond market does, indeed, make it more attractive than it was with a starting point of 1.5%. I wrote about this a few weeks ago. But the error here is in evaluating the relative attractiveness of “boring bonds” to “dividend growth” as opposed to evaluating “boring bonds” to earlier decade “boring bonds,” or to other strategies for capital preservation with an income focus. All things being equal, the delta may be less in terms of relative attractiveness, but the fundamental portfolio objective is not remotely controversial.

Behind door #1:

Whether you are a current withdrawer from your portfolio or a compounder/accumulator of capital, pretend you put $1 million into a 10-year Treasury. You are going to get $41,000 per year of income, it will not go down, it will not go up. You will get your $1 million back in ten years, and you will have received $410,000 of interest along the way. Now, if yields drop along the way (they will), you could sell at a profit, but that wouldn’t change the fact that you now have to reinvest at a lower interest rate, defeating the purpose. And yes, rates may go up along the way, but to capture those, you would have to sell your bond at a loss, also defeating the purpose. The yield captures the math of bond pricing as rates move. It is a highly efficient market. You are investing $41,000 of income over ten years, with a return of principal at maturity.

All of that is a lot better than doing the same for 2%, or $20,000 per year, or $200,000 in total over the years.

And door #2?

Now, let’s say you did the same thing with a dividend growth portfolio with a starting yield of 4.1%. First, the negatives: You are not guaranteed your $1 million back in ten years, but rather are subject to market value. More on that later, but for the risk-averse, that may seem like a negative relative to the return-of-principal par value of the bond. But let’s look at the income. In both cases, you receive $41,000 in year one (though even intra-year of year one, there is the likelihood of dividend income growth, but we’ll pretend there isn’t). But let’s say that income grows at 6% per year … “Fixed income” is the description we use for the bond market (it’s a tautology); “dividend growth” is the description we use for this equity orientation (stop me if I am going too fast). 6% is on the lower end of what we target in annualized dividend growth across a portfolio, but I want to use conservative projections.

So in your second year, the income goes to $43,460 (6% higher than year one’s $41,000). But then year three goes to over $46,000, and year four to $48,760, and year five to $51,685, and year six to $54,786, and year seven to just over $58,000, and year eight to $61,558, and year nine to $65,252, and year ten to just over $69,000.

Comparing the two

Now go back to year ten of the bond portfolio – $41,000, same as year one, $41,000. So in the final year, the income is up +68% in the dividend growth scenario versus the bond scenario. That sounds like a lot. But do it over the entire ten-year period, and the income delta: $410,000 for the bond investor versus $540,000 over ten years for the dividend growth investor, a +32% premium in income for the whole ten-year period.

So that seems open and shut to me – the ten-year bond has a place in a client portfolio as a “boring bond” – a risk mitigator – a component of the asset allocation – but a “fixed” 4% can’t compare to the dividend-growth portfolio starting at 4%. Right? But wait, there’s more.

The income of the 10-year Treasury is federally taxed as ordinary income (same for CD’s and other corporate bonds); the dividends are taxed federally at 15-20%, max, depending on the bracket. So there’s that. But we’ll leave taxes out of this from here and re-visit that issue of asset pricing.

What is the value of capital on a “fixed income” bond instrument? Par value – $1 million in, $1 million out. Not bad – you got your money back.

What is the value of capital on a portfolio of dividend-growing stocks that have grown their income in aggregate by 6% per year? Well, perhaps it is in the range of historical averages and is somewhere around high single digits per year. Perhaps it has big down years and big up years, and averages something more muted, like 5% per year. Either way, an underlying asset growing its cash flow organically each year is increasing its value by some degree. Maybe you assume a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of just 4% … then your $1 million is worth almost $1.5 million. Maybe you use the same 6% that we are talking about the income growing … Then the value is a tad shy of $1.8 million.

Now, run all these numbers again if the dividend growth was 7%, or 8%, or 9% per year (I speak from experience). It begins to get unreal on your paper or calculator.

Do you see my point? Two instruments that start at the same value ($1 million), the same yield (4.1%), and the same first-year income ($410,000) end somewhere around $750,000 apart – about 75% ($130k of more income combined with 500-800k of more value, so I split the baby and called the total $750k).

And I consider all of these inputs historically and economically conservative, across the board.

But there’s no free lunch!

This seems so obvious, right? But it isn’t. Why would one turn down that kind of premium return for the bond option versus the dividend growth stock option? Volatility, for one. Stocks go up and down in price, period. I can’t make it untrue, and when we can hide day-to-day mark-to-market pricing with private equity, we lose that income generation and growth (and liquidity). So visibility of mark-to-market bothers people.

Would you pay $750,000 for this? Well, I guess the answer to that question tells you what to do with your next $1 million, doesn’t it?

Other Observations

Of course, the bond portfolio will have volatility, too (in case you haven’t noticed). Bonds go up and down as well, and over a ten-year period, there will be various events that cause both ups and downs. But the counter-arguments to the bond volatility point are good ones (1) Bond vol should be less than stock vol (this year is a very rare occurrence with bond price volatility), and (2) Even with up and down volatility, bond investors do know along the way that they have par value waiting for them at maturity. Fair enough.

Would you pay $750,000 for this? Well, I guess the answer to that question tells you what to do with your next $1 million, doesn’t it?

But there is another big problem with this hypothetical scenario: What will interest rates be at the end of the ten years? For ten of the last ten years, the answer has been: “something lower than 4%.” One is, at best, taking a very big risk that they will be investing themselves into an assured pay cut, perhaps as much as 50%, in ten years. Not good.

And there is another big problem with this. Inflation. Now, perhaps you do not believe that 7-8% annual inflation is here to stay (I certainly do not). But even (like me) one who believes we face Japanification in the economy for a couple of decades to come believes there will be some price inflation (even if it is significant disinflation from current levels). Let’s say it is the same 1-3% per year for the next decade that it was for the last couple of decades … (and the consensus view is that it will be in the higher range, not lower, but I am using my view, not the consensus). So at 2% inflation, that means your matured $1 million will have the purchasing power of $781,005 in ten years. At just 2%.

Okay, now I am starting to pile on.

Caveat Central

Bonds belong in a portfolio where an investor’s psychology and comfort level warrants a volatility bandwidth that makes something less than a 100% equity allocation appropriate. I fully stand behind my belief that where bonds are needed to diversify volatility and smooth expected outcomes, I am more fond of allocating at a 4% starting spot than a 1.5% starting spot. The decision is not binary between “dividend growth” and “boring bonds” – each investor’s allocation should really absorb all of those investors’ particulars (from timeline to emotional temperament to liquidity needs to goals to experience to tax status, etc.). My point is simply that there is a significant opportunity cost to believe dividend growth is now less attractive just because of the current yield of bonds.

Don’t get fired!

Dividend cuts are a kiss of death for management teams in corporate America (how often does a company cut their dividend and not see the CEO and CFO get fired? … trust me, it’s rare!). How does a management team best protect themselves from having to cut their dividend? By not paying one, they can’t afford to pay! How do they measure that? By actually knowing the company they lead – its cash flows – its business prospects – its strategy – its competitive landscape, etc. A dividend payment ought to reflect what management believes about the present and future state of the business. Revenue growth, earnings growth, and Free Cash Flow growth are tangible metrics that matter.

In conclusion

After a 9-month bear market (and counting), a > -20% drop in the S&P 500k, and a multiple contraction from >23 to <17 (all without a recession or much earnings drop), the S&P’s yield is still only 1.9%. There is way, way, way too much reliance on pollyannish hopes for earnings growth, margin expansion, multiple expansion, and so forth. Bonds may offer a starting yield comparable to dividend growth, but as time goes on, that benefit disintegrates. Equity indices don’t even offer half of the starting yield.

Investing is about risk/reward calculations and cost/benefits analysis. You can see why those processes landed me where they did.

Chart of the Week

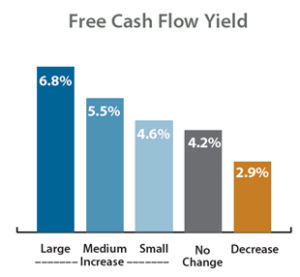

Lower P/E ratios in stocks have generally meant larger dividend increases, but plenty of low P/E companies may be dividend cutters, so the P/E ratio is a tricky indicator for anticipating outsized dividend growth. While the P/E is an imperfect measurement, the Free Cash Flow Yield of this largest dividend growers has been a rather useful metric in evaluating the capacity for dividend growth.

*Miller-Howard Research & Analysis, Quarterly Report, Q3 2022, p. 3

Quote of the Week

“But the one thing I’m pretty sure of is that [crypto] doesn’t multiply, it doesn’t produce anything. It’s got a magic to it, and people have attached magic to lots of things.”

~ Warren Buffett

* * *

So there is your Fed-free investment primer for the week. I am sorry if there was a little too much math. You know what to do if you have questions.

Go Trojans, Go Pacifica Tritons (our girl’s volleyball team plays in the CIF championship tomorrow), and enjoy your weekends. I will see you in the DC Today on Monday.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet