Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I hope that you found last week’s Dividend Cafe on Credit to be informative and interesting. It’s summertime, and some people are more focused on the beach and the sun than syndicated loans, but not me. The cool factor has never quite been something people associated with me, and if I have to enter the month of August with a double issue of Dividend Cafe on Credit markets, I am going to do it.

But it isn’t just for the least cool of us like me – as I mentioned last week, Credit is a sine qua non in our economy. It is not an end for economic activity, but it is a vital part of the means. Oil and gasoline are not the points of driving, but good luck driving without them (okay, fine, or without electricity – the point is the same). The point of last week’s Dividend Cafe was that Credit is both a signifier or messenger about economic reality and, at the same time, a catalyst or influencer on economic activity.

I wrote last week’s Dividend Cafe in sub-optimal conditions (I will leave it there) and knew as I was wrapping it up that there was more to say, so I committed to a second part. So consider today some “extra credit” (see what I did there) – and jump on into the Dividend Cafe!

|

Subscribe on |

Half-full or half-empty

I wrote last week about the fact that defaults were not growing much in either investment grade or high yield bonds and that even in levered loans where the rates float higher as the Fed hikes rates, the defaults are not bad. They are higher than they were before this tightening cycle started, but they are not extreme – not even close. They may worsen. The Fed may want them to worsen. But they are not recessionary, and they are lower than any honest person would have forecasted if they knew the Fed would hike the Fed Funds rate 550 basis points in fifteen months.

But there is more to the story than just low defaults. Issuance is also an issue (no pun intended). What I mean by that is the generation of new productive credit matters to future economic conditions just as defaults matter to current economic conditions. What is the story there?

(h/t Michael Poulos)

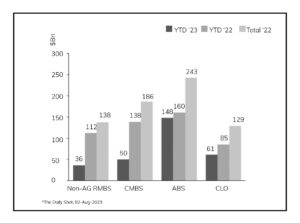

Here you see a pretty sharp downturn in the volume of credit issuance in residential mortgages (non-Fannie/Freddie), in commercial mortgage securities, in asset-backed securities, and in collateralized loans (which are pools of syndicated bank loans).

So low defaults (good), but declining issuance (at least worthy of a question).

Issuance for issuance’s sake?

I actually, though, do not believe that declining issuance is necessarily a bad thing. I always believed that excessive loan issuance for residential mortgages in 2002-2006 was a very, very bad thing and that extending fewer loans to more good borrowers is the ideal (read it again if the shock and controversy hits you hard). So, in theory, a decline of issuance could, might, potentially mean a simple protection of loan quality. I like that theory and wish it were the case. But there is a counter-factual that is hard to argue with:

What we see here is that Treasury issuance has skyrocketed, and the percentage of total debt represented by Treasury bonds has grown significantly. Now, of course, you could argue that T-bill issuance skyrocketed and corporate issuance plummeted just in arbitrary happenstance to their own dynamics, but I will not be making that argument. In this case, it seems very clear to me (within credit markets) that government credit is crowding out private credit.

Why do we care?

I made this point about issuance last week as it pertained to bank loans – the institutional volume of new bank loans is very, very small. That is one of the reasons the money supply has collapsed – new loans mean new money and new loans are not happening. So why do we care when structured credit (the aforementioned residential and commercial mortgages and other asset-backed markets) sees a huge drop in new loans, as do bank loans?

A few possible reasons:

(1) In the corporate world, one of the largest uses of corporate credit is M&A (the mergers and acquisitions that are so common in American enterprises). When borrowings collapse that would fund M&A, and M&A collapses below logical levels, you very likely have lethargic companies carrying on that attract resources away from more productive ones. While this may not exactly sound like rocket science, I am really against bad M&A, but really for good M&A, and a collapse in credit takes out M&A as one potential tool in feeding productivity and optimal allocation of resources.

(2) We need new factories, warehouses, and other commercial real estate projects to enhance our quality of life. A turndown in credit for such projects limits the growth that would come out of new facilities, projects, and engines of activity that such capital expenditures represent. These commercial real estate projects are inherently capital-intensive, and tightening of credit not only makes individual projects potentially less profitable, it potentially makes for less individual projects, period. And many of those projects are quality-of-life and productivity-enhancing projects that need credit to see the light of day.

Quality control

As I mentioned last week, it is very rare for credit to just freeze up entirely. Those 2008 moments are the exception, not the rule, but wow, are they ever ghastly when they happen? But the more common form of credit tightening is not a freeze out but a diminished access and increased cost. And that can actually lead to higher quality available for investors.

As you can see, when fewer loans are getting done, the quality of the loans gets better, and here you see that debt divided by earnings is the lowest it has been in about a decade. Less leverage means less risk and higher quality, so all at once, investors have better credit protection, yet the economy has less total credit.

Default reckoning

I talked last week about how low the defaults have been thus far in both investment-grade bonds, high-yield bonds, and leveraged loans. We have barely $20 billion of levered loans in default right now (over the last twelve months!) out of what is a trillion-dollar marketplace! My view, shared last week, is that this is largely because companies were able to secure terms and liquidity back when the credit going was getting good (2020/2021), and so they have time (call it a year or two more) until cash needs and capital costs and other things come to a head. This may be too sanguine of a view, but it does seem to have been the case for the last year or so.

Now, the default rate on bank loans has picked up, but it has not even picked up to a historical average level yet – let alone worse than average. But there are hundreds of billions of dollars of loans due in 2-3 years – over half of which are B- rated credits (or lower). Will credit still be tight and expensive, then? I obviously do not know. If it is, will there be an avalanche of defaults and bankruptcies, then? Oh, I think that is very safe to say.

So what does that mean?

(1) There are bad times coming in 2-3 years, or

(2) Credit has loosened up before then

Simple.

Parsing the categories

Bonds refer to debt instruments that take on the form of a security – a tradable, liquid instrument with a maturity date and coupon that are registered, regulated, and generally for large borrowings of large companies.

Loans refer to sums of money businesses borrow from banks. These days they are almost always syndicated and pooled together and available to buy as packages, and they generally have a floating-rate characteristic that makes them attractive to investors and troublesome to borrowers. These are generally high in the capital structure but not secured by any particular asset other than the ongoing life of the business.

Structured credit refers to debt for some borrower connected to an asset – residential mortgages, commercial mortgages, or other asset-backed vehicles that securitized a credit instrument out of it (credit cards, car loans, student loans, aircraft loans, etc.).

Direct lending refers to non-bank lenders who lend based on the cash flows of a business but not through the bond market or bank loan market. The cost of borrowing (so the yield to the investor) is generally higher than other borrowing mechanisms, and rates usually float. But this can represent access to credit where it may be otherwise unavailable, and it may be quicker to come by and also less visible to the public eye.

Private credit also refers to non-bank lenders, who can go fast, who do not securitize in the bond or loan market, who charge a bit more, who can act with confidentiality, and who also often use floating rates. These may not just be cash-flow backed like direct lending loans but might be backing an entire business transaction like an LBO. One of the huge evolutions in credit since the great financial crisis, and even more so since COVID, is the market share private credit has taken from bonds and syndicated loans in financing leveraged buyouts and all sorts of large credit needs.

Direct lending funded more than double the M&A volume so far this year that high-yield bonds or leveraged loans did. Across the board, credit’s drop in access has been more about a change in lender (from one of the aforementioned categories to one of the others) than it has a total collapse of the credit market.

With all thy getting, get certainty (and value)

It is a fair question to wonder why any borrower would pay more money to borrow from one lender than they might have to from another, and private credit cost more than other vehicles. And obviously, one answer is just cheaper lender A (banks or bond markets) won’t lend to me; more expensive lender B will lend to me (private credit). That could be the case sometimes. But I think the real factors are much more than just “funding or not funding” … Really, it comes down to:

(1) Execution certainty. Yes, getting funded with certainty – but also with terms you know are real and will stick and not change around market conditions

(2) Ability to work with lenders entrepreneurially, creatively, and flexibly. The private credit world has this thing called “businessmen” and “businesswomen” – not merely “bureaucrats” and “risk managers.” Banks can be very programmatic. The private credit world invites a different access to value.

(3) In cases of distress, there is more flexibility for “workouts” than other credit vehicles have. Bonds and loans have courts and documents and trusts, and other such statutory processes. Private credit may allow for negotiations and creativity when things go poorly.

(4) And finally, value-added unrelated to the transaction itself. A bank may give you a toaster. A private credit lender may give you genuine intellectual capital and strategic partnership. This. Stuff. Matters.

My final takeaways before you take your test

To recap the basic message I have wanted to convey about credit in this two-part series:

(1) Credit is tightening but has not reached a point of high defaults or overly restrictive access and cost of capital, yet

(2) There is a “maturity wall” in 2-3 years where a lot more new credit will be needed, and if credit remained tight would create a lot of defaults and problems

(3) Those problems in #2 would not merely be for the borrowers or the lenders, but for the economy at large as it would impact jobs, wages, profits, and counter-party activity

(4) I find it unlikely that credit will be allowed to stay tight through the election year and the maturity wall that follows

(5) Demand for corporate loans, bank loans, and other credit activity is dropping quickly. Defaults and distress may be low, but new issuance is way down.

(6) Private credit has thus far been the winner, and I believe it will continue to be, gaining market share from the bond market and the loan market

(7) From an investment standpoint, an “all of the above” menu in one’s portfolio is a very good idea. We work tirelessly to have extraordinary exposure to extraordinary managers in private credit, direct lending, structured credit, syndicated loans, high-yield bonds, etc. – because we want the full opportunity set in front of us to utilize on behalf of our clients. To that end, we work.

(8) Declining credit conditions are here. That is already known. What is not known is how much they decline from here. A few notches lower into 2024 and a soft landing will not happen. A stabilization and recovery, and a recession will be averted. CREDIT will determine RECESSION.

And if you know all eight of these things, you have earned your extra credit.

Chart of the Week

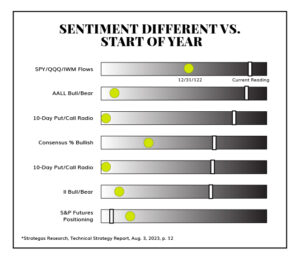

You can see why the contrarian in me doesn’t like this.

Quote of the Week

“Boredom is the deadliest poison, and it is a truism that strikes hardest at the most comfortable.”

~ William F. Buckley Jr.

* * *

I am off to New York City on Sunday and will be working from the office there all of next week before returning to California for two weeks after that. Next week’s Dividend Cafe is going to be fun, but I will leave you in suspense. Let’s just say it will be foundational to what we believe.

I welcome all questions and compliments, and criticisms, and I wish you a very good weekend. This is such a privilege for me – to write Dividend Cafe each week. Thank you for reading it, and clients, thank you for your trust. I assure you we are trustworthy. To that end, we work.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet