Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Here is my promise to you in today’s Dividend Cafe – the entire thing, from start to finish, is apolitical. Now, that is not actually true, and maybe by the time I am done writing, I will explain what that means – where there is a political dimension to this subject. But in a deeply divided country that over the last ten days has experienced all it has experienced, and in an investment commentary communique, I think it is appropriate that this particular edition not say the word “Trump” or “impeachment” or “riot” or any of the words that have rather aggressively filled the news cycle for a couple weeks.

That is not to say those things are not in my head. I actually wrote a 7,000-word article on my entire personal assessment of the Presidency this week, non-market related. I am trying to limit my intake of the daily screaming matches that exist on respective news networks and social media at the other political side, while simultaneously trying very hard to stand for the principles for which I have always stood.

But the subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe (which will surely be extended into next week’s as well) is the great macroeconomic subject of our time. It did not begin with COVID – it began in earnest out of the Great Financial Crisis, and I can argue that it began before that. It carries with it implications for every asset class on the planet in every geographical region on the planet, and it is the subject of great debate.

But you know what is nice about the inflation vs. deflation debate? Really serious economists and really passionate strategists that vehemently disagree with each other tend to discuss this debate, and sometimes even strenuously object to their opponent’s views. Yet I have never seen the nastiness if the world of economic in-fighting that has currently taken over pop culture.

So consider the debate of this subject my safe space. =) And consider this an apolitical journey into some really interesting, significant, and disputed terrain.

The crux of the matter

If you believed that interest rates were going to be 0-2% would you invest capital differently than if you believed they would be 5-7%?

If you believed that inflation would run 1-3%, would you invest differently than if you believed it would run 4-6%?

Does one’s view on interest rates and forward-inflation impact their expectations for P/E ratios (market valuations)?

If credit is going to tighten (ease of access to capital and cost of capital), would that alter one’s allocation to corporate credit, private equity, public equity, and a host of other risk asset classes?

Would one’s view on the U.S. dollar potentially influence their allocation to domestic vs. foreign assets?

And regardless of how one’s views on interest rates, inflation, credit, and currency impacts the decisions, they make on investment decisions, will all of these things impact the expected return on all asset classes (whether or not it alters your weightings in such asset classes)?

And if these things impact expected returns in various asset classes, does that have practical significance to one’s financial planning, accumulation goals, withdrawal goals, and other such tangible dimensions of wealth management?

The answer to every question above is YES, and pretty much all emphatically so, which means that every person reading this has a real dog in the hunt when it comes to the great economic debate of our time:

Deflation vs. Inflation

The two sides

Let’s take away the two extremes that could be said to exist out there – the hyper-inflationistas that constantly predict a Zimbabwe or Argentina like predicament to the United States, and the perma-bear deflationists that don’t merely believe in the predominance of deflationary conditions, but believe they will lead to the extinction of our Republic. Maybe one of these camps will be proven right someday (they won’t), but what we do know is that (a) It won’t matter if one of these two camps is right; and (b) They have been so wrong, for so long, that I want to focus on lower hanging fruit. I would add a “c” here – no one who actually runs real money is in one of these two camps. It is a business model (doom and gloom), with one angle or the opposite angle used to generate clicks and hits and sales and all the things. In fact, some have actually vacillated between both extremes at different times, covering two distinct customer bases with two distinct theories of the case! Either way, I want to stay in the fringe-free zone for our purposes.

And those two sides are:

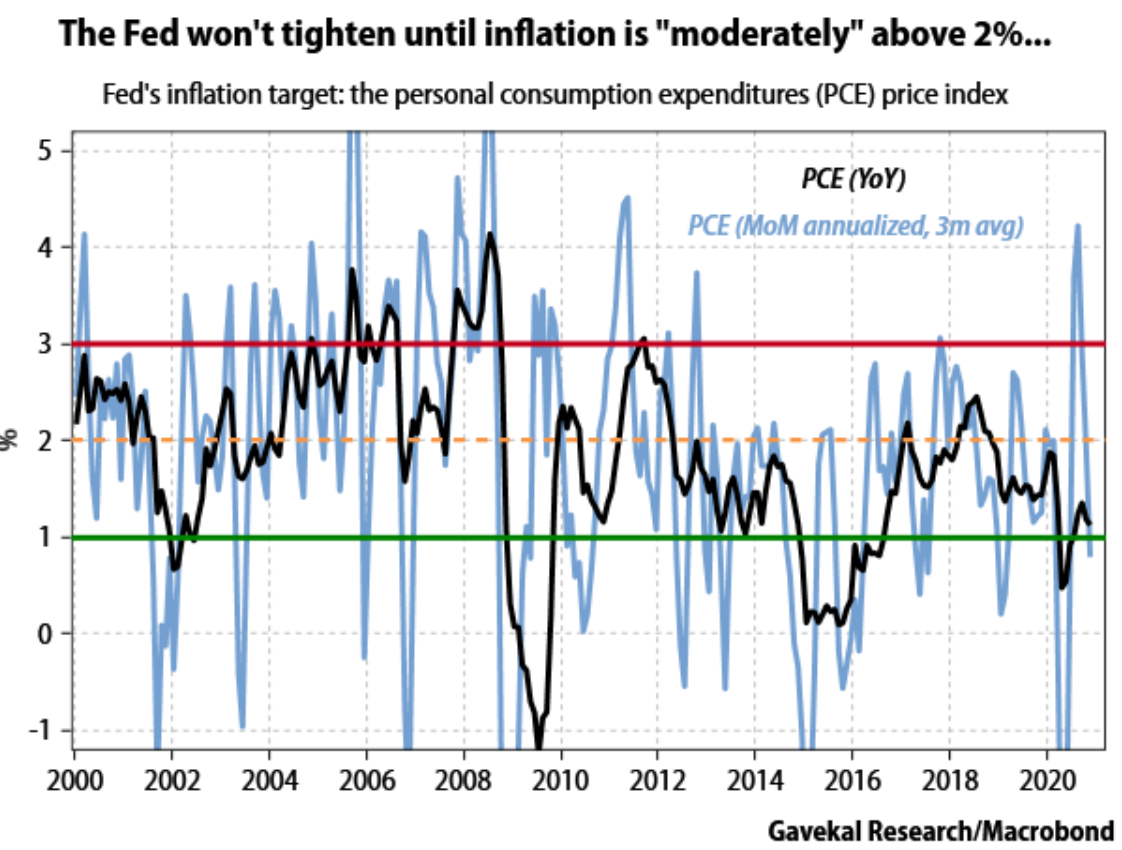

(1) The belief that the fiscal and monetary stimulus you see eventually “works,” meaning, they get the inflation they want out of these efforts, only after receiving it the inflation genie will be out of the bottle and hard to put back in – ergo, inflationary pressures on bond yields, P/E multiples, and financial metrics. The rational bunch in this camp acknowledge this has not been the case but is pretty self-aware in their forecast that “this time it’s different.”

(2) The belief that the fiscal and monetary efforts we see now have reinforced a debt/deflation cycle, and “more of the same” is creating, well, “more of the same.” The conclusions most from this camp draw (including yours truly) are a form of “Japanification” of the American economy.

Using Key Prices to Frame the State of Affairs

A year ago, oil prices began dropping (and then really dropping as COVID came), the ten-year bond yield began dropping (and then really dropping as COVID came), and the dollar was inching higher …

Now, ten months after the beginning of the peak-COVID moment, oil prices are rising, bond yields have risen, and the dollar has gone down for 8 or 9 months …

Does the change in direction of these three price indicators means something, and if so, what does it mean?

On one hand, there are some who believe it is all a false signal – that oil prices are headed back to $20 – that negative yields are coming – and that the economic weakness of Japan and Europe are here and not getting any better.

But on the other hand, there are those who say rising yields, rising oil prices, and a declining dollar all mean the inflationary thesis is back, and that the deflationary bogeyman of yesterday is gone, and now we have violent inflation to worry about, evidenced in the three price reversals I talk about.

My view can safely be called “none of the above.” Oil prices are not merely a by-product of the high-level inflation-deflation debate within global economics. They are at their core a commodity price, which by definition means they are subject to the laws of supply and demand. And an increase in the trajectory of oil demand combined with the unprecedented efforts to impact the supply levels (lower) can very easily mean higher oil prices (as it has), without it speaking (necessarily) to the broad inflation/deflation debate.

But what about bond yields? Well, 1.1% on the ten-year is not stoking the inflation fires in my soul. Yes, we are off of the 0.7% yields that came in of Q2 last year (for now), but as we spent the better part of a hundred years with the ten-year between 4% and 10%, with inflationary spikes in the 1970’s hitting 15%, you’ll forgive me for not seeing 1.1% as signs of a tsunami of inflation.

*TradingEconomics.com, 1920-2020, Jan. 15, 2021

The thesis I would suggest to you makes the most sense of the very current conditions (oil prices going higher, the ten year normalizing at a higher place than, ummmmm, zero, but still at pitifully low levels, and the dollar having dropped but not rapidly continuing to do so, are all a by-product of the current reflationary (normalizing) conditions out of economic panic, and by-products of hyper-aggressive policies (fiscal and monetary), but none of which indicate “all is well” and none of which indicate “the pendulum has swung the other way.”

Money Supply ≠ Inflation

Money supply is up 25%, but really 36% with cash held up by the Treasury. That cash was used to meet margin calls last spring and to beef up cash balances as a precautionary measure with COVID looming. And we know how risk asset prices have since been bid up as a result of this additional cash (growth stocks, credit, real estate, etc.). The question others now pose is: will this excess cash now find its way to bidding up the price of goods and services (i.e., inflation).

The challenge in predicting so is two things:

(1) It hasn’t happened elsewhere, meaning Japan for thirty years, the U.S. post-GFC, and the EU post-Greece. The major, undeniable precedents we have for these particular policy tools being used to create inflation out of the increased money supply they generate have simply not done so.

(2) The economics tell us otherwise. Irving Fisher’s quantity theory of money tells us that Money Supply X Velocity is the key ingredient and that Velocity is not influenced by the quantity of money. Central Banks can influence money supply; we know this. But they cannot increase velocity at will – certainly not by merely increasing supply – and in fact, we know that other economic forces have put downward pressure on velocity for a long time (namely, excessive government spending that crowds out private sector activity. This is a vicious and self-reinforcing feedback loop.

A fatal problem in modern economic thinking

A consistent worry I hear is that a successful vaccine result, easy monetary policy, additional fiscal stimulus, and economic recovery, all put together mean – big inflation coming. And of course, a lot of economic activity combined with excess money supply (which I am defining as the legitimate excess of money relative to the goods it is chasing) is inflationary. But the problem with the worry I am describing is its constant confusing of growth with inflation – of assuming that organic and healthy economic activity is necessarily inflationary.

This is the mistake embedded in the Phillips Curve – the antiquated (well, antiquated by history and reason but not necessarily in the academia where Fed governors are created) – the implied belief that inflation and growth are one and the same. Lower unemployment is only necessarily correlated to inflation if one believes that healthy, organic economic growth is inflationary. The fact of the matter is that higher productivity driving lower unemployment can be counter-inflationary if higher productivity is “soaking up” that excess money supply and reining in unit labor costs. And inversely, higher unemployment has not proven to be anti-inflationary (read: the 1970’s) as we can have both bad things at once, too.

What am I saying here? I am saying that what creates inflation is an excess of money supply relative to the goods and services in the economy. The Fed cannot control all of these equations, as (a) The last 12 years in our country proves, (b) The last 12 years in the European Union prove, and (c) The last 30 years in Japan prove.

The Fed’s inability to create inflation is a direct consequence of the deflationary forces the Fed is sighting stemming from excessive government debt extracting productive money from its best use in the private sector. So if you want to worry about something, do not worry that – heaven help us – the vaccine might bring about normalcy, and that might prove inflationary! – it’s absurd. Rather, worry about how we do not get to pack the economic growth punch we would pack if it were not for the constriction of growth we are fighting due to excessive levels of debt.

So what DOES it mean?

For an investor, with all of the other current economic realities right now, what would slightly higher bond yields mean? The major takeaway should be that P/E ratios have a harder time rising, which creates headwinds for so-called “growth” stocks and creates better conditions for so-called “value” stocks. As I stated above, “inflation” seems a much less logical outcome to me than the rotation-into-value thesis does.

Caveat, warning, qualification, not fine print

I can write week after week after week about the various realities of the U.S. economy, our economic growth, our spending, our debt levels, our debt ratios, and our central bank policies. All of it matters, and hopefully, I will draw important and actionable conclusions from such analysis. But if my analysis in all this pretends that there are no other countries on earth, I am going to get it all wrong. I have followed macro commentary for 25 years that has (a) Gotten a bunch of premises right on aforementioned categories and (b) Gotten virtually every conclusion wrong. There are a few things that play into this depending on the pundit I am criticizing, but one of the most common mistakes I see is ignoring the importance of the relative realities when discussing these things.

If the U.S. is doing bad things to their currency, and yet regard for the U.S. currency seems to be unshaken, could it be that other countries are simply doing things as bad or potentially worse?

Greenback Gusto

The above is not merely a hypothetical. And it is one of the reasons that one’s view of the dollar, and certainly one’s view of foreign exchange (forex) markets at large, ought to be marinated in humility. I have never seen predictions more frequently wrong than from the best forex traders out there – that’s right, the BEST are wrong more than any other predictive space in financial markets.

Our view of the dollar has always been as follows: In short-term and even intermediate-term windows, we know the dollar can decline in value relative to a basket of global currencies (2003-2007), and in those short and intermediate-term windows, it can rise against a basket of global currencies (2014-2019). We try to invest capital in such a way that those movements have little impact (beneficially or negatively) to the overall portfolio. As for the prediction of the dollar “collapsing” and “losing world reserve status,” we remain not merely skeptical but borderline amused.

Short-term, you’ll often find us bearish on the dollar

Mid-term, you’ll almost always find us agnostic.

And long-term, we believe it will move relative to other currencies far more on what they are doing than it is doing, but without impact to our portfolio results and maintaining its reserve status for decades to come.

Don’t get me wrong – all things being equal, short term dollar movements, if predicted accurately, WOULD help those overweighting this and underweighting that … The issue is that no one seems to ever get those things right, ever. Why add a dimension of risk and uncertainty to the already-risky and uncertain world of investment management – especially when that new dimension increases your chance of making a mistake?

Financial Vocabulary

It occurs to me with the last section that the terms “dollar weakness” and other such framings of “what to expect from the dollar” have two totally different contexts that are almost never clarified in the media, and that are almost always used interchangeably, and therefore, incorrectly.

(1) “The dollar is losing value” – this can mean (and it is how we talk) what the dollar’s exchange value is versus another currency (or basket of currencies). It is that relative value I refer to above.

(2) “The dollar is losing value, part 2” – this can mean “the dollar buys less than it used to” – in other words, a comment on purchasing power, which is to say, inflation.

Neither use is right or wrong, but they are different. When we speak to a decline in purchasing power, that does not speak to what the dollar is worth versus the Euro or Yen or Yuan (per se). And when we speak to what it is worth versus another currency, it doesn’t speak to the purchasing power question.

Exchange rates matter when you travel. Exchange rates matter when you buy or sell an asset in one currency different than the one you will convert to. And inflation and purchasing power matter when it comes to the affordability of goods and services in your day to day life. But they are two different topics. And short-term conjecture on “the dollar” means very little to investment policy.

Pulling it together

I have so much more to say on this topic, and these topics I will, indeed, allow for a “part 2” next week. Essentially, what we are looking at here is a “larger” pressure of debt/deflation overpowering the “smaller” periods of inflationary pressures, which in no way contradicts the fact that certain policies will still create inflated policies (we only have had significant price inflation in higher education, health care, and housing for the last 20+ years). Investors have to deal with deflation. Shoppers have to deal with modest inflation. And both things come from the same policies—more elaboration to come.

Chart of the Week

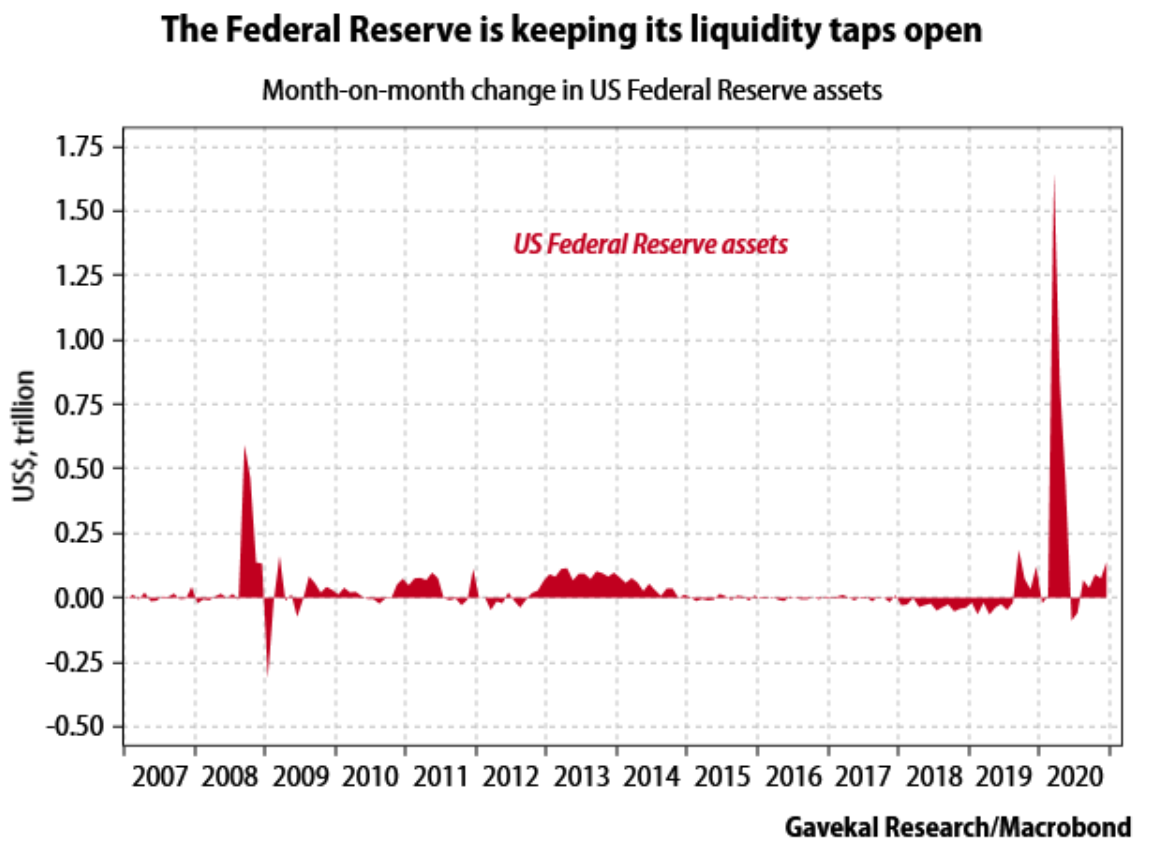

Let the visual of this chart sink in. Look at the 2008 increase and the “gradualism” of the 2009-2014 increase thereafter, then compare it to the 2020 moment. More on this next week!

Quote of the Week

“Capital is not the scarce resource.”

~ Michael Milken

* * *

I hope you didn’t find this week’s commentary too intricate. My goal was to get out of the news cycle and into the economic mind of The Bahnsen Group and where we see the good and bad of present conditions going. I need next week to further pull it together. In fact, next week I will even talk about where crypto/bitcoin fits into this dialogue. So take it all in, reach out any time with any questions, and we’ll reflate the conversation next week!

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet