Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I was going to use this week’s Dividend Cafe to continue the discussion on China, one that I more exhaustively began three weeks ago, then expanded upon last week. And in fact, I have done a podcast interview with Louis Gave of Gavekal Research on this very topic, poking him and pushing him around his thesis that China’s strategic objectives in their bond market and currency are aligned with the objectives of U.S. investors. But I am going to hold this for next week, first of all, to give my communications team time to properly curate and edit that interview, but also because I believe there is a more timely message that is needed this week.

By the time you are reading this, I presume Federal Reserve Chairman, Jerome Powell, will have given his speech in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. I am very purposely writing this before such a speech has been delivered or pre-speech teasers on its content have been circulated. I am, therefore, obviously writing it before I know the market reaction to the speech (stock or bond market).

This is on purpose. I do not want the focus to be on what is or is not said at Jackson Hole today, or what the market does or does not do after such speech.

Far more than anything that is said today is the fact that there even is such a focus on it to begin with. And this hype, this prioritization, this captivation in financial markets, with one man giving one speech on one day, is symbolic of where I feel so much has gone wrong.

And what THAT is and what it specifically means to you is the subject of this week’s Dividend Cafe.

First things first

I do consider myself a critic of the Federal Reserve, but I am not sure that means the same thing as it means for a lot of people. There is kind of a cottage industry of Fed haters out there who impugn some really awful motives to them, have highly conspiratorial views about the Fed, and who generally see the whole operation as some form of plot to enrich evil insiders. So if that is what people mean by criticizing the Fed, count me out. I generally find when poking deeper with such folks that the most basic and remedial of monetary vocabulary is over their heads, and that their views are more political and especially sociological than anything else.

The cottage industry of more fringe Fed critics is not a camp I want to be remotely associated with, and if anything, I think that camp has done great damage to the cause of actual constructive criticism of our nation’s central banking policies. The fringe element has, in many cases, caused the baby to be thrown out with the bathwater by allowing a perception to take hold that Fed critics are all lunatics.

The fact of the matter is that there are highly competent and intelligent Fed critics out there who are not anchored to a wild conspiracy theory, and who do not believe the motives of the Fed governors are malignant and corrupt. Jim Grant is an example of a highly respected economist and historian who is very critical of the Fed’s policies at times but does not question their motivations. Danielle Dimartino Booth worked as a policy advisor to former Fed governor, Richard Fisher, yet now has become a leading voice in the dangers of credit market distortions as a result of Fed policy. In both cases, people can agree or disagree with the criticisms they offer, but they are offered intelligently, charitably, and cogently.

So I start off this piece saying, “yes, I am a Fed critic,” but “no, I am not one of the fringe lunatics.” I hope that helps set the table a bit.

Do we even need a Fed?

I think this is another key element that almost represents a sub-division of the camp of Fed critics I am very consciously wanting to separate from … I do believe the country needs a central bank. Now, I happen to believe in a pretty modest role for such in an ideal state, and I believe a right-sized Fed would have a different mandate than both the dual mandate the Fed legally has now and the triple mandate it functionally has. But I think a “lender of last resort” role is perfectly legitimate in our economy, and I think most attempts to paint the mere existence of a central bank as an assurance of inevitable doomsday have, well, not gone very well.

How many mandates?

Let me clarify my comment up above on the Fed’s legal dual mandate (which I don’t actually like) and their functional triple mandate (which I really don’t like). The 1977 Reform Act passed by Congress and signed into law by the President (then-President Jimmy Carter) amended the original Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and explicitly tasked the Fed with “promoting the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” The first two there – maximum employment and stable prices – are what is meant by the “dual mandate.” The mentioning of “moderate long-term interest rates” is more of an assumed or desired state that comes out of the first two – that interest rates will be moderate only in a stable macro environment. The policy objectives are the first two – maximum employment and price stability.

But why do I refer to a third mandate in practical or functional terms? It isn’t in Congressional legislation – there is nothing codifying a third element – the Humphrey-Hawkins Act doesn’t mention it. So what am I talking about?

The clear and obvious policy objective, something I believe began under Greenspan in 1998, where the coddling of risk assets like stocks, credit, and real estate, became considered a centerpiece of the Fed’s job description.

The Ghost of Volcker

I will spend most of my time critiquing the unwritten third mandate, but allow me to point something out regarding even the tensions in the “dual mandate” that I believe is problematic.

Sometimes, price stability means tightening that will temporarily impact employment markets negatively. That trade-off has become politically untenable. The other side (hurting price stability to allegedly help labor markets) is more politically palatable.

Former Fed Chair, Paul Volcker, famously “broke the back” of inflation with tightening in the 1980s. He was not concerned with political feasibility.

“I am wholly convinced — and I think I can speak for the whole Board and whole Open Market Committee — that recognizing that that objective for unemployment [4 percent] cannot be reached in the short run — the kinds of policies we are following offer the best prospect of returning the economy in time to a course where we can combine as full employment as we can get with price stability.

I bring in price stability because we will not be successful, in my opinion, in pursuing a full employment policy unless we take care of the inflation side of the equation while we are doing it. I think that philosophy is actually embodied in the Humphrey-Hawkins Act itself. I don’t think that we have the choice in current circumstances — the old tradeoff analysis — of buying full employment with a little more inflation.

We found out that doesn’t work, and we are in an economic situation in which we can’t achieve either of those objectives immediately. We have to work toward both of them; we have to deal with inflation. And the Federal Reserve has particular responsibilities in that connection.”

But the basic reality of human nature is that a dual mandate with competing aims where one is popular and one is not is going to see one picked at the expense of the other. This seems quite intuitive to me.

An odd definition of independence

The Humphrey-Hawkins Act of 1978 called for “improved coordination among the President, the Congress, and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System” – Section 2(b)(3).

[Of course, the Humphrey-Hawkins Act also called for a balanced budget and a focus on exports in trade policy, so apparently, legislation has a certain selectivity in terms of which parts are actually adhered to, but I digress.]

But the Act further codified the requirement that the Fed submit written reports to Congress twice a year (both the relevant Senate committee as well as the House Committee). These reports are now accompanied by heavily televised committee appearances (back to back chamber committee meetings twice a year).

Now, the President appoints the nominee for Fed head, and the Senate must confirm him or her. So there is already an embedded politicization – though that is reasonably benign compared to countries that do not even pretend their central bank and their elected leadership wear different hats. And candidly, I am not sure that in theory there is anything problematic about semi-annual reports and Congressional testimony. Yes, the elected officials at these committee meetings often reflect a monetary IQ that would make my 5th-grade son look like MIT material, but the mere requirement of testimony and reporting does not intrinsically threaten independence.

What has become embedded in the national reality, though, is an accord between Fed and Treasury that is deeply problematic. I recall this Time magazine cover like it was yesterday – where mainstream media was presenting the Treasury Secretary, the President’s chief economic advisor, and the head of the central bank, as a sort of singular unit – a trinity if you will – working together to save the world.

I support all attempts to save the world, by the way. But I might suggest a little humility is in order as to when the world needs to be saved and who is doing what that actually saves the world. We likely have a more anti-fragile economy when we do NOT need three people to secretly work together to save it, but again, the point I am making here is that this is a newer phenomenon in the last 20-25 years – that the Fed head is a quasi-government actor working in formal coordination between the monetary and fiscal side of the house. And it is quite subject to abuse that needs to be understood.

The GFC is where it got real

Where the “accord” between Fed and Treasury become basically baked in the cake was the Great Financial Crisis. Post-GFC, I am not sure most laymen could tell you which hat Hank Paulson wore, which hat Ben Bernanke wore, and which hat Tim Geithner wore. They were all considered the “team” working to, well, once again, save the world.

And I should be very clear – the NY Fed’s oversight of troubled NY banks (Tim Geithner), the Fed and its vast policy tools involved in the crisis aftermath (Ben Bernanke), and the Treasury Department and its legislative push with Congress known as TARP (Paulson), all warranted coordination. What is at stake here is not the horror of these guys being in each other’s speed dial, obviously. Rather, it is the disintegration of a separation between the jurisdiction and objective of each respective body. And when those separations are respected in normal times, they will not need to be so diminished during crisis times.

The COVID moment pushed further the notion that we have a single economic authority in this country – a sort of joint venture known as the “Fed/Treasury.” Secretary Mnuchin and Chairman Powell were joined at the hip (certainly the elbow) as literally trillions of dollars were moved through both fiscal and monetary policy vehicles to address the pandemic.

Special purpose vehicles that the Fed creates are now routine as “backdoor bailout” instruments, sometimes quite profitably, sometimes not. They require equity capital from the Treasury (taxpayers) and then leverage from the Fed (printed money), but more than that – they require the suspension of independence.

And maybe we are okay with this. Maybe as a society we “want them on that wall, we need them on that wall.”

But if we think their TARPs and TALFs and Maiden Lanes and Cares Acts and SPVs and all the alphabet soup of GFC and COVID policy come without trade-offs, we fool ourselves. We lie to ourselves. We kid ourselves. And we will not be ready for what fragility has been invited into the system.

So what is the beef?

I believe the problem with an economic system that waits with bated breath for one man to give a speech at a luxury resort as if all human action is dependent on his every word is that we have taken the focus in economic life off of human action, and on to central planning.

I promise you, economic outcomes are about human action, and the more the focus is on that, the better the outcomes will be. I care about this message a great deal.

Getting Inflation Out of the Way

I understand that many critics of the Fed focus their efforts on the inflationary results of overly accommodative central banking. I think a lot of this is misguided, but I don’t want to beat this horse right now. I have written about the inflation/disinflation debate all year, and my thesis is that it is government spending above a healthy proportion to the size of the economy that becomes disinflationary and creates stagnant economic growth, The isolated impact of a central bank on inflation is a completely different subject.

For what it is worth, a can of Campbell’s soup cost $0.25 cents fifty years ago, and it costs $1 now. That quadrupling of price equates to 2.8% inflation per year for the last fifty years – largely with above-trend inflation at the beginning of this era and much below-trend inflation in the second half of this era. BUT …

In this same time period, food went from 13.3% of a household’s disposable income to just 8.6% … These various things can all be measured in a number of different ways.

Breaking down the real concerns

At the end of the day, I divide my concerns of modern Fed policy into three categories:

(1) Distortions

A philosophy of central banking that keeps emergency measures on in non-emergency times, or fancies itself as the “smoother of the business cycle,” distorts our ability to measure risk relative to reward. It alters risk-taking because it forces people to shoot the basketball when they can’t fully see the hoop. The interest rate is a price, and as the great Jim Grant says, it should be discovered, not imposed. When price discovery is so meaningfully altered by the interventions of disinterested third parties, purchase decisions are made that otherwise wouldn’t be. Companies survive that otherwise wouldn’t (and shouldn’t). Resources get misallocated. A great new innovation doesn’t get the funding it would have gotten because a dying zombie company kept capital it otherwise wouldn’t have kept.

From borrowing to lending to building to investing to measuring to analyzing to all sorts of verbs relevant to an economy, present Fed policy exacerbates the tendency to boom cycles and then bust cycles, and forces an economy to run without an accurate scale.

(2) Dependency

As much as any economic truism we have seen in my adult lifetime, present monetary policy requires more of it to provide a constantly diminishing benefit. An entire housing market is now completely and permanently dependent on 2-3% interest rates. The notion of 5% or 7% on a home mortgage (par for the course for decades) would decimate the national housing market and put us into a depression.

Economic growth has become dependent on credit expansion, and credit markets are dependent on a low cost of capital that can only be imposed by intervention. In Q4 of 2018 when a central bank last tried to “normalize” to a natural level, credit markets threw up and forced the Fed back to hair-of-the-dog policy.

The United States government that is supposed to be independent of the Fed relies on the Fed to keep the price of their debt at absurd levels, as do the sovereign governments all over the world. The world’s super debt cycle is kept alive by monetary interventions, leaving a black cloud of uncertainty over how it plays out. Uncertainty is the enemy of innovation.

There is no plan anywhere for how the world can be less dependent on easy money. We just simply take for granted that it will always be. This is classic hair-of-the-dog policy, and it is at the very essence of fragility in the economic order.

(3) Inequity

Finally, social cohesion is irreparably damaged when the policy framework seems to favor those with assets (rich people) over those without (non-rich people). We can talk about IRA’s and pension funds and 401k accounts all we want. And we can talk about mortgage rates for middle-class homebuying all we want. These things are all legitimate. But the benefits of this monetary policy are not evenly distributed, and the perception is that the rich are getting richer at a faster pace in a way that undermines the social order.

My view is more nuanced than this perception. When asset prices inflate for reasons unrelated to organic growth – when they go higher because of a central banker’s well-intentioned intervention – the middle-class asset owner does benefit, and the upper-class asset owner does benefit. But the person who did not yet own assets did not. And the reward for that person is exiting college and entering the job market at a cartoonishly stupid price level in the housing market.

It’s not right.

Will tapering QE damage markets?

The modest tapering of QE is at worst a contributor to short-term volatility and provocation of algorithmic trading. Unlike the summer of 2013, tapering is now highly expected and therefore priced, and much like the second half of 2013 and well into 2014, markets ultimately shrug it off (and in that case, actually rallied). The build-up of more and more excess bank reserves (often offset by reverse repos very few understand) is simply irrelevant to functioning financial markets right now and irrelevant to the ability of public companies to generate profits. Interest rates pursuing any path to normalization is marginally superior to the alternative of artificially lower rates, in so much as interest rates are price signals, and distortion of those signals hampers price discovery, and price discovery is the sine qua non of a free enterprise system.

Conclusion

I hate the fact that the world is so obsessed with a Jay Powell speech in Jackson Hole just as I hate the fact that the world was so obsessed with the size of Alan Greenspan’s briefcase in the late ’90s. I have managed money through the great era of monetary policy expansion.

It expands my responsibility for caring for clients, in that risk and reward are skewed at a time when individual responsibility is lacking.

That is a by-product of the Fed, to some degree. And while I believe these are earnest and well-meaning intellectuals, I also believe that individual families and investors live in a more fragile economy because of their well-meaning interventions.

So that end we work.

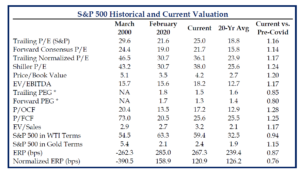

Chart of the Week

Strategas Research,Valuation Chartbook, August 23, 2021

Quote of the Week

“Ignore any hawkish chatter from Reserve Bank presidents — they don’t matter / never have — though they are ‘useful idiots’ in maintaining the institution’s inflation fighting credibility.”

~ Rene Aninao

* * *

Looking forward to picking up the China subject next week. I welcome your feedback on this subject here and certainly want to answer any questions you may have.

In the meantime, think nothing of Jackson Hole unless you are actually there on vacation yourself. Enjoy your weekend. And remember that humans act, with or without interventions.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet