Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

I wrote last week about the multi-year (and indeed, multi-decade) beliefs we have about macroeconomic conditions. In a nutshell, I made the case that we face a form of “Japanification” where the diminishing return of fiscal and monetary efforts to goose our economy from the impact high debt has had on its growth leads to yet more debt and also less growth, all as part of a feedback loop.

I wrote the week before about the uncertainty of what will happen in the economy this year and presented the most objective cases I could both for and against a 2023 recession. The market seems to be voting against a severe recession this year so far. This causes me to believe a recession is more likely. Many of the most famous “perma-bears” of our land have heavily leaned into the assurance of a severe recession. This causes me to believe one is less likely. (I really do crack myself up).

A fair question out of the “longer-term” outlook we have (Japanification) and the “shorter-term” outlook we have (recession possibility without recession certainty) is why we see Dividend Growth as an extremely compelling solution in these scenarios. Dividend Growth Equity investing is “risk investing” (there is no maturity date where a par value is promised by the federal government). There are plenty of forms of risk investing, and I want to explain why I believe dividend growth is uniquely suited for these moments.

So jump on into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

A refresher for the veterans and a synopsis for the newcomers

Whether we were talking about a robust bull market, a problematic Japanification, a 1970s stagflation, a 2000-2010 bookends of bursting bubbles, a flat but boring and tepid economic growth, or any other scenario one could envision, we believe dividend growth investing to be as “all-weather” as one could imagine. First of all, every one of the above scenarios has happened in the last ~fifty years, and in each case, dividend growth has passed its tests with flying colors. But beyond the empirical testimony of history, let’s revisit the basic points that formulate our thesis:

(1) The companies that are able to grow their cash distribution each year are generally just better companies, period

(2) The mathematical edge that comes from dividend reinvestment is a compounding miracle wrapped inside a mathematical miracle, producing leverage in the “eighth wonder of the world” (the compounding of capital) and creating a beneficial opportunity out of inevitable market volatility

(3) Those withdrawing capital from a dependably rising stream of dividends versus the underlying asset itself immunize themselves from the risk (assurance?) of inevitably volatile prices

(4) Dividend growth companies have achieved better results in long-term time horizons in a measurable way (both absolute and relative performance, especially when viewed in the context of real-life withdrawals and portfolio activity). But equally important, they have done such with much less volatility and portfolio stress

(5) Dividend levels above the absolute level of inflation combined with the growth of those dividends at a higher rate than the rate of inflation provide the most reliable and mathematically cogent defense against eroding purchasing power we have ever studied

Each of these points (and many others) has been exhaustively defended and exposited in our writings, videos, and podcasts over the years, not to mention my book on the subject. But perhaps this succinct summary scratches your itches …

Understanding the alternative

Stocks have never, ever, ever, ever made sense as a long-term investment apart from the profit-making reality of great companies. Take away profits and the growth of profits, and no one wants to buy a stake in the profits of a company, let alone pay a large multiple for such. Take away profits from your investment calculus, and all you are doing is praying you catch one of those unprofitable companies that run up in price and that you sell to a bigger sucker than yourself before it drops. Note: If you do that, you will make money. Further note: Good luck.

So once we establish that the reason ALL stock investors are investing is related to the earnings power of the companies they are buying, the debate simply moves to “what do we want the companies we own to do with the profits they generate.” I want them to de-risk and reward my clients and me with a large portion of those profits, all the while retaining enough for future capital expenditures and balance sheet fortification. The alternatives have a very volatile track record over time, with many ending in utter disaster and all of them becoming dependent on multiple expansions (valuation) over time for their return.

Booms and busts do two things – they reward the multiple expanders more in booms, and they punish them more in busts. And they make a withdrawal stream from such a virtual impossibility, or at least a mathematical fatality in many situations.

Deflating GDP and deflating valuations

In some environments of deflation, one may see multiple expansions. The argument goes like this: “Growth is so low, we need to pay up for those companies that show signs of growth, so instead of 30x earnings, let’s pay 50x earnings because growth is hard these days, and this hot cloud/software/plant-based/cool company grows a lot!”

Fair enough. But there are a few problems: growth rates slow, and multiples get re-priced – violently. Many aspirations for future high growth do not materialize. Many companies fail. The hot companies become popular and become dependent on the investing generosity of their not-super-sophisticated investor base. The seeds of their own destruction are sown.

In a period of less robust economic growth, the value of dependable cash flow becomes more important.

Japanification increases uncertainty

High P/E stocks are not just risky because they often require higher P/E ratios, still. And they are not risky just because the comparative interest rate may rise, undermining the valuation. Fundamentally, they are stocks priced assuming certain things about a lot longer of a time period into the future than lower P/E counterparts. High P/E stocks mean knowing more of the future than is knowable. And they invite volatility that eats at returns without a continued dividend reinvestment to turn that volatility into an advantage.

What to expect

More companies succeed in the future in a period of GDP growth than in a period of tepid GDP growth. More “new” companies come online and change the world in the 1980s and 1990s than in the 2010s, when GDP is double or more than it has been as the output levels increase appetite, incentive, capital formation, production, and consumption. The declining growth of Japanification makes the dependability of entrenched, proven businesses more valuable, and it makes the investor objectives tied to strong balance sheets, less debt, and more free cash flow more attractive. It aligns an investor with reality and not hope. And it decreases the investor’s dependence on popularity and increases the investor’s dependence on an aligned management team. Economics is human action, and may we all never forget it.

Why quality matters

A great fallacy in how people view our philosophy of dividend growth equities is the belief that debt ratios and balance sheet strength matter because of the immediate risk of a dividend cut or even firm solvency. In fact, a company with excessive debt may sustain its dividend for a long time and have no real solvency risk at all but do so by issuing new equity or selling other quality assets on the balance sheet that it would otherwise prefer to keep.

In short, quality matters not because tomorrow Armageddon comes but because a lack of quality might just lead to a slow, subtle death that does the same thing Armageddon does, just over a longer, slower period of time.

Conclusion

The case for dividend growth is evergreen. The primacy of cash flow is constant. Our determination to use the mechanical and substantive dynamics of dividend growth investing as a powerful tool for the financial goals of our clients is the end to which we work, relentlessly.

A brief postscript: The Big Short meets The Big Misnomer

Steve Eisman, the hedge fund manager formerly of Frontpoint (one of my great 2007-2009 investments) who famously shorted the housing market and was played by Steve Carrell in the hit movie, The Big Short, was recently interviewed on the Bloomberg podcast Odd Lots. He had this to say about Bitcoin, and since his two arguments are essentially identical to the two arguments I have been making for years, I felt the need to share …

“So I remember during Covid, you know, I was out on Long Island in the North Fork basically living there. And I would come back to the city every Tuesday to visit my mother. And so I would drive to the city, there would be no traffic, and it would take me about two hours. So I listened to podcasts. What else are you gonna do? Right? I even listened to this podcast every now and then.

But one of the group of podcasts that I listened to were the so-called experts on Bitcoin. And there are always two questions that I had. Number one, why is Bitcoin a currency? And number two, okay, it’s a currency, but how should it trade? Now on every single podcast, they completely skipped over the, “why is it a currency issue?” that was just a given <laugh> and that’s not a given to me. We can get back to that.

But it wasn’t given. The second part of the story about how should bitcoin act, they all had the same opinion, which was as fiat currency, which is government issued currency, has been terribly debased because of all the deficits that all these countries have issued. But it’s very hard to short fiat your currency because they all trade relative to one another. So if you short the dollar, your problem is that in a basketball team where everybody’s five four, the dollar is five 11. So it’s hard to short the dollar. Because it’s taller than the other currencies, even though, quote unquote, it’s been debased. So therefore you should buy Bitcoin as a hedge against the debasement of all currencies.

Okay. So let’s accept that theory for a second. If that’s the case, then Bitcoin should go up when people are nervous and rates are going up and Bitcoin should go down when rates are going down everybody feels good. And the problem was it actually did the opposite. Right? It would go up with everything else speculative. And it would go down with everything else speculative. So what was the point? So, you know, Bitcoin is up a lot this year because it’s up a lot with everything else speculative. Now you can’t have a currency that moves 25% every six months. That’s not a currency. That’s a speculation. And the thing I don’t understand about Bitcoin is what problem is it solving? You know, is there a problem with currencies? I mean, the last time you went to the store and you, you pulled out a $20 bill you paid with your credit card. Did the store owners say, oh no, I don’t take dollars. I mean, it’s not even an issue. And by the way, the currency markets are the most liquid markets in the world, you know, I like to say, how long does it take to buy dollar euro done? A billion dollars? Done. That’s how quickly it is. So I, I don’t understand what Bitcoin solves and I don’t understand the purpose of owning it other than it’s another form of speculation.”

When “speculation” goes up, Bitcoin goes up. When speculation goes down, Bitcoin goes down. That is not called a hedge – it is called the opposite of a hedge. And I believe even after the carnage of last year, a lot of people still own it under a thesis that is the opposite of reality.

Chart of the Week

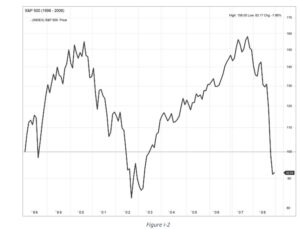

This was the market (S&P 500) in the first ten years of my career: The boom of dotcom, the bust of dotcom, the recovery and credit boom, and then the Great Financial Crisis.

Fortunately, dividend growth kept this chart from being the tale of client portfolios. This period changed my life and career and animated in me a cerebral appreciation for dividend growth investing.

*Case for Dividend Growth Investing, Figure 1-2, Post Hill Press, 2019

Quote of the Week

“It is not by augmenting the capital of the country, but by rendering a greater part of that capital active and productive than would otherwise be so, that the most judicious operations of banking can increase the industry of the country.”

~ Alexander Hamilton

* * *

Please do reach out with any questions at any time. Dividend growth will never be discussed at our firm as a trade, a tactical play, or a hot idea. It is a philosophy that connects what we know to be intrinsically true about investing to the practical realities and needs investors have. And that applies in 1990s America just like it does in 2023 America. Some things are the same yesterday, today, and forever.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

dbahnsen@thebahnsengroup.com

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet