Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

If there is one thing that animates me it is the application of real-life economics to investing. I have always been obsessed with economics – both theory and application – but it is in more recent years that I have really found it a calling to synthesize the foundational truths of economics to financial markets.

And truth be told, that calling transcends the applications of economic theory to financial markets. I believe properly understood economics has profound implications for all aspects of human living. My extra-curricular endeavors in economics (the book I wrote last year, the class I teach at the high school I co-founded, Pacifica Christian) are all extensions of this passion I have for a free and virtuous society. But yes, applying these things to financial markets is my real passion, and the inability and disinterest the financial advice community has for applying economic principles to markets is a constant source of irritation.

Today’s Dividend Cafe is about the labor market – the state of jobs in America. For 99% of the media and even economic analysts these days this is an econometric subject. In other words, it is a data point that provides an input to a spreadsheet, and from there carries some numerical relevance to another input (i.e. if wages are here or unemployment is here, then consumer spending is possibly going to be here, etc.). Worse, it is often just a mere political data point, perhaps an even more imbecilic understanding of work than even reducing it to an economic data point.

But economics is the study of human action around the allocation of scarce resources. Our understanding of what is happening and not happening in the world of work will be improved to see it through the lens of the human person. Political and econometric reductions will tell us almost nothing, and in fact, may tell us things that aren’t true at all.

Investors and actors in financial markets need a fuller understanding of current realities in American labor. To that end, we work … (see what I did there). So jump on into the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

Some Data of My Own

My belief that economics cannot be reduced to data does not mean there is no data on the table to discuss. In fact, the qualitative point I intend to make today is extracted from a quantitative reality:

There are THREE MILLION people who have left the workforce in the last two years who say they have no intention of returning.

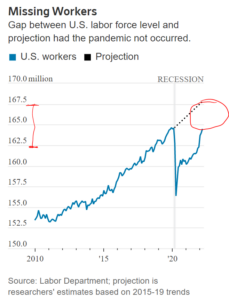

While the total labor force losses are offset to some degree by new entrants to the workforce, the “trendline” growth of where the labor force is supposed to be is structurally impacted by a net of three million people, period.

This has been discussed in a lot of ways by a lot of people, but I think it is important for Dividend Cafe to offer perspective on causation and implication that may be lacking in press reporting.

Why is this happening?

We all know what initially shocked and awed the labor force 25 months ago, and that was the onset of COVID and subsequent shutdown of the American economy. No one could be expected to know what the “stickiness” of the unemployment was going to be at that time, so I am not critical of the fact that everyone’s predictions were so painfully wrong. When 22 million people lose their jobs in a month, we can all be forgiven for not knowing how quickly those 10 million positions would be re-filled.

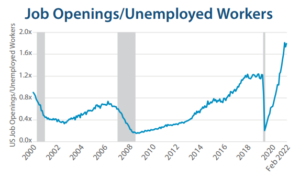

But unlike any recession in American history, at some point a year or so after the initial shock of lost job positions, it suddenly became evident that we were no longer dealing [primarily] with the lost job positions, but actually (and shockingly) the lost job applicants.

It is one of the most shocking reversals in history. The debates in 2020 amongst mostly well-intentioned people went something like this: “I think the unemployment rate comes back down to 6% by the end of the year and then levels out from there for two years” – and then a more optimistic person would suggest 5% and a more pessimistic person might suggest 7% – but it was all about when those job openings might be back in play to be re-filled. People didn’t know, and people love leaning into a more pessimistic view as it makes them sound smarter in a crowd (I consider it a coping mechanism, but I digress), but again, reasonable people could debate what the magnitude and the pace of job position recovery was going to look like post-lockdowns. And the fact that the lockdowns kept hemming and hawing, never fully ending, with divergent results in different states, being juxtaposed with school openings (or non-openings), etc., etc. made it all a very complicated and painful experience.

And yet in the end, a year or so after the initial March 2020 lockdowns, the entire script was flipped. The structural and embedded losses of job positions from COVID provided to be non-existent. The structural and embedded unwillingness of employers to re-hire proved to be non-existent. The predictions of structural and embedded demand erosion proved to be the worst economic call since those who were sanguine about housing in 2006. Pessimism that job openings would come back was rooted in the utterly absurd idea that humanity was going to be content to not shop any more, eat any more, travel any more, or otherwise live any more.

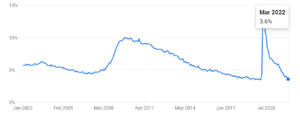

Because humans act, life returned to normal – and in fact, did so with a vengeance. And humans acting meant employers needed workers. So we didn’t stay at 9% unemployment, and we didn’t debate a 6% or 7% leveling. Instead, we returned to pre-COVID job openings, to pre-COVID weekly jobless claims levels (or better), and to a pre-COVID unemployment rate.

*Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 1, 2022

But all was not fine

So what is the problem? Employers needed jobs again. Demand was up again. The shock and awe of lockdowns were overcome and the worst of the potential pain was avoided. Tragic job losses proved short-lived and people who needed work to survive could find work again. All was good in the universe, right?

No. Because instead of a society needing to find work for those who needed it, we became a society needing to find workers for those who need them. And that has led to a fair amount of weeping and gnashing of teeth around what it has meant economically.

2021 Inflation’s Many Fathers

I don’t want to belabor the inflation point because it gets talked about ad nauseum, and it is not like I have exactly ignored the subject. Much of the talk has been about the causes, with more informed and non-agendized commentators accepting the multiplicity of causes behind this period of price escalation.

I most certainly understand that extra government transfer payments can play a role in the short term of money sloshing around; all the while serving as a long-term repression of economic growth (see: Japan).

I certainly understand that excessive monetary policy can become both distortive and inflationary, the latter being especially true in a period of stable or increasing velocity; all the while serving as a long-term repression of economic growth (see: Japan).

But I do believe government mistakes have created and exacerbated much of the current inflation – it’s just that I do not believe the transfer payment and monetary policy impact on money supply is chief among them. Rather, I believe government policy best-case exacerbated this labor shortage, and worst-case created it.

Fred Smith, CEO of Federal Express, had this to say in the Wall Street Journal this week (emphases mine):

“People make the supply chain this arcane subject. Hell, it was a lack of people to off-load trucks, and of people to drive the trucks. There wasn’t a big problem going through those ports out there. They weren’t even working three shifts. It’s simple: you couldn’t move it once it got ashore … We were 40,000 package-handlers short, and there were people in the media saying that the stimulus checks didn’t have anything to do with that. [Such people] are divorced from the world we’re living in … if I’m getting a government check there’s less incentive to go into a warehouse.”

If you want more of something, subsidize it

Fundamentally, from the initial exhaustive shutdown (in hindsight, a colossal mistake that will be treated mercilessly by history), to the ongoing “quasi-shutdowns” (i.e. closed gyms, bars, restaurants, schools, etc.), to the large and perpetual cash payments given throughout (standard unemployment, yes; but then multiple additional government cash payments on top, and then extensive supplement to unemployment on top of that), to the school closing complications, there were policy causations to those leaving the workforce, and not returning to the workforce.

These things are called incentives. And because I know that central planning cannot properly steward the affairs of an economy, lacking the knowledge and incentive alignment to do so, I have a true appreciation for the reality of human action in driving economic decisions. Humans respond to incentives because that is the way the world works. On the margin, incentives drove a departure from the workforce and a sustainability to such departure.

So it’s all the government’s fault?

With apologies to my friends who want me to blame the government for everything wrong in society, no, it is not. I am very critical of certain decisions President Trump made in all this (his relentless support for more direct government payments, for one), but this is not all his fault. I am very critical of certain decisions President Biden has made in all this (the March 2021 spending bill of $1.9 trillion with the long-term extended federal unemployment subsidies chief among them), but this is not his fault. My opinions here, though truthful, objective, and accurate, and perfectly aligned to make everyone mad at me. There is blame for both Presidents here, and there is too much blame given to both Presidents here. And I don’t say that because I like the squishy middle – I am a movement conservative Republican through and through – I say it because it is the truth and if everyone could just stop politicizing this for five seconds I truly doubt anyone would differ.

The policy framework, riddled with errors, bad judgment, and unintended consequences – was very damaging here. But it took a cultural malady to pair with a policy malady to get us to this point. And in that cultural/policy pairing we find the reason for the current labor malaise.

Where we are

So we right now have 1.2 million fewer people in the workforce than we did before COVID. And as mentioned earlier, that is over 3 million people less than we should from a trendline standpoint. That is a lot of workers not making goods or delivering services. That is a lot of productivity and efficiency taken out of the marketplace. It is, for those who can follow this logic, a lot less growth … (unless you believe growth does NOT follow productivity).

These numbers do not tell the whole story because numbers never tell the whole story. Understanding “why” and “what” and “how” and “if” and “when” and all these sorts of human nuances and dynamics are the essence of economics; the number is just a marker.

And what I will say about all the qualifying color is that we suffer exponentially in the future from the current numbers. We cannot measure easily in quantitative form the impact of diminished job skills and job readiness for those out of the workforce for a prolonged period of time. We cannot measure easily the enhanced social safety net expense that will inevitably come along with this cultural dynamic. And we certainly cannot measure easily the public health or emotional health or existential impact costs that this will create.

Conclusion

I will write in Dividend Cafe and in whatever mediums God gives me for the rest of my life of the need for economic growth, not to mention its teleological function. But the last thing we need when striving for greater telos in society is a declining workforce. The last thing we need when striving for greater supply to meet greater demand is a declining workforce. The last thing we need when facing $31 trillion of national debt is declining productivity that comes from a declining headcount of workers. The last thing we need in a time of social and cultural division is exacerbated divisions that naturally flow from a wider gap between the connected and disconnected.

There is no fed funds rate – not 0% and not 10% and not anything in between – that can optimize economic and cultural conditions like a productive, thriving workforce. May this great priority be efficiently understood as the policy need of the hour. And where policy hits its limits in efficacy, may we pray for a paradigm shift away from this “great resignation.” Work is the verb of economics.

A note on last week:

I spoke about private equity last week and the opportunities in private market investing. A fair question that I hear almost all the time is: “What if private equity is overvalued, and you are missing the danger of the purchases made at high valuations?”

Private equity collectively (as an industry) is sitting on $1.38 trillion of undeployed cash – what we in the biz call “dry powder.” I would argue that it could be a massive benefit to the industry if there is a contraction that allows that cash to be deployed at lower prices.

Now I ask you – how many PUBLIC MARKET indexes (say, the S&P 500 or Nasdaq), have $1.38 trillion cash in them?

**********

Chart of the Week

*Miller-Howard Investments, Q1 2022

Quote of the Week

“Without meaningful work we sense significant inner loss and emptiness. People who are cut off from work quickly discover how much they need work to thrive emotionally, physically, and spiritually.”

~ Tim Keller

* * *

Wishing you all a productive and fulfilling weekend, and looking forward to a wonderful last week of April. I love my work. It makes every week something to look forward to.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet