Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announced a 50 basis point rate cut this week, which is also known as a half-percent cut (i.e. 0.50%). This represents the first interest rate cut from the Fed since March 2020, when COVID was beginning. The markets, which knew it was coming, responded Wednesday as they often do with bizarre behavior (up 200, down 200, rinse and repeat five times in two hours), and then Thursday saw all risk assets rally substantially. I am way too nice of a person to say what I think of most media commentary since the announcement, so all I can do is devote a Dividend Cafe to understanding this. I fully expect it to be (a) Too nice for some, (b) Too mean for some, (c) Too political for some, (d) Not political enough for some, (e) Not Jekyl Island-ish enough for some (moving on), and (f) Not enough about the USC-Michigan game for some. I have sympathies to one of these camps, but for the first five all I can say is … I promise this will be objective, fair, and reasonable.

So let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe, where the first cut in 54 months, the first rate change in 14 months, and the beginning of a new era are the week’s subject.

If interested, a chat with Stuart Varney on the Fed, dividend growth, and more here. And a chat with The Big Money Show on economic policy and political catastrophism in investing here.

|

Subscribe on |

Modern history

Here is a very, very quick summary of Fed rate policy since the financial crisis:

- The GFC (Global Financial Crisis) kicked off in September 2008 with the failure of Fannie, Freddie, Lehman, and AIG, and the Fed moved rates to 0%

- The Fed holds rates at 0% basically for eight years (they increased 0.25% in December 2015 and then another 0.25% in December 2016)

- Throughout 2017, they slowly increased by a whopping 0.75%; throughout 2018, they increased by another 1% (always in 25 basis point increments).

- In early 2019, they stopped hiking rates (the Fed Funds rate target peaking at 2.25%) and began cutting in mid-2019 (despite prior stated intentions to normalize rates)

- We enter 2020 with a 1.5% Fed Funds rate, and by March 2020, facing global COVID shutdowns and other insanity, the Fed brings rates to 0%

- Rates stay at 0% until Spring 2022 when they finally hike one-quarter of a point. But they then begin an aggressive rate-hiking posture in the summer and fall of 2022, and by late summer 2023, the Fed Funds rate finds itself at 5.5%

- Rates stay at that 5.25-5.5% target rate range from August 2023 until this week.

- This week, the FOMC cut rates by 50 basis points to a target rate of 5% and indicated plans for another 50-75 basis points of cuts by the end of the year.

Quantitative something

It should be added to our discussion here: In 2018, the Fed was ALSO doing “quantitative tightening” while they were slowly raising rates (i.e., pulling liquidity out of the financial system via something called “roll-off” – allowing treasury and mortgage bonds they had bought to mature without reinvesting the proceeds). By late 2018, with liquidity very tight, credit markets revolted, spreads widened, equities dropped, and in January 2019, the Fed changed its mind. This is very important. In 2020, when the COVID moment saw them bring the Fed Funds rate to 0%, they also accelerated quantitative easing, buying $5 trillion of bonds onto their balance sheet in the next two years. In the aforementioned period of time when the Fed was raising rates (spring 2022 through summer 2023), they were ALSO doing “quantitative tightening” – that is, “rolling off” about $1 trillion of money from their balance sheet, essentially extracting liquidity from the financial system. Only this time, the credit markets did not revolt; risk assets did not stall; and the Fed kept it going even as they “paused” their rate hikes. Since the Fed left rates alone a little over a year ago, they have continued to “tighten” by “rolling off” bonds on their balance sheet, but at a slower pace (about $25 billion/month instead of $80-100 billion per month).

All in, the Fed reduced its balance sheet, which peaked at $9 trillion in spring 2022, to $7 trillion, where it sits now. Risk assets are sitting pretty. Credit spreads are tight. The Fed has said it will continue to reduce the balance sheet, albeit at a very slow pace.

So, to be clear: What the Fed is doing now, according to them, is (a) Easing monetary policy on the one hand (reducing rates) and (b) Tightening monetary policy on the other hand (bonds coming off their balance sheet)

One of these things is like the other

So consider:

2008-2015: Rates low, quantitative easing (two tools devoted to easier monetary policy)

2016-2018: Rates higher, quantitative tightening (two tools devoted to tighter monetary policy)

2019-2022: Rates low, quantitative easing (two tools devoted to easier monetary policy)

2022-2024: Rates higher, quantitative tightening (two tools devoted to tighter monetary policy)

In every period since the financial crisis, both policy tools have been ALIGNED. Right now, as of September 2024, we face the first time where one tool giveth, and the other tool taketh away.

Why?

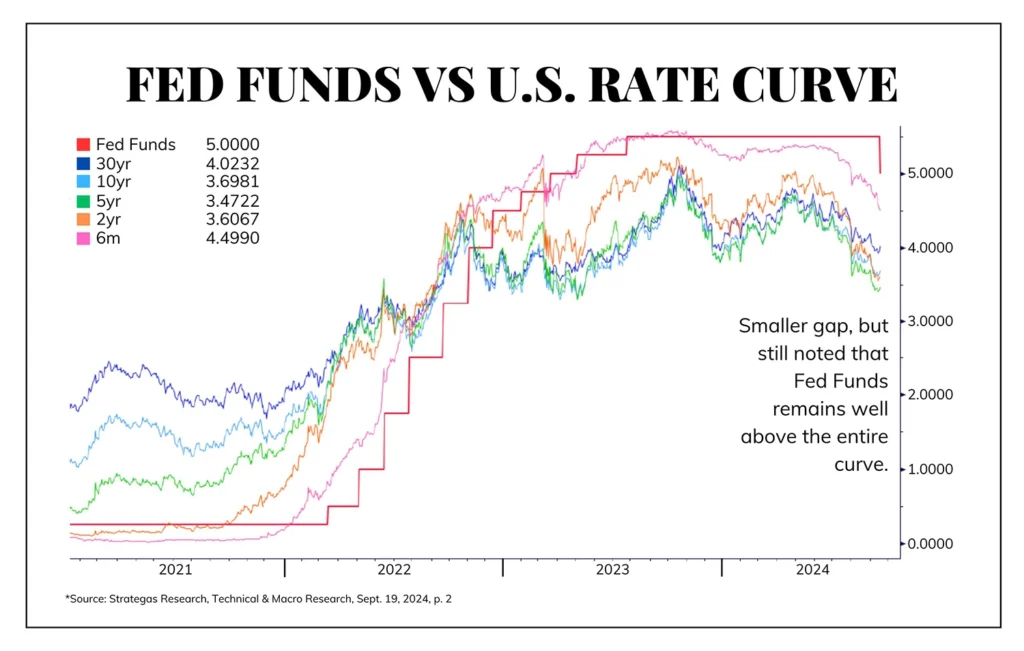

The short-term borrowing rates remain very high (90-day T-bills are 4.7%, around the projections for the Fed Funds rate, as is typical). The ten-year is at 3.7%, and the two-year is 3.6%—so it is not inverted any longer (after about two years of violent inversion) but still dead flat.

A positively sloped yield curve reflects something we in the business call economic normalcy. Okay, I made that term up, but I am quite confident I could get my 14-year-old son to label a positively sloped yield curve as normal in about 20 seconds (are there any TikTok videos about it?). It is NOT normal to cost the same to borrow money for a short period as it is for a long period. It speaks to concerns about longer term growth, period. The Fed can control the very, very short end of the yield curve because the Fed Funds rate dictates overnight borrowings from banks (as previously explained here in the Dividend Cafe). But there is only so much it can do about ten-year bonds. Insurance companies, widows, banks, corporations, savers, pension funds, and foreign countries have a point of view about growth, inflation, and so forth. And the ten-year bond yield, over time, reflects expectations for nominal GDP growth.

But not if the Fed can help it! If the 10-year expectations are too low, the short rate is too high (because the Fed needs more time to cut it down to size). The yield curve is showing something that various Ph.D’s (and also homeless people at Bryant Park) would call “abnormal,” then maybe, just maybe, continuing to tighten with QE/QT is one way to TRY and hold the long end higher. At the same time, they bring the short end lower with rate policy.

Not such a crazy theory, is it?

Why cut rates?

At the end of the day, I believe the Fed needs to get the short-term borrowing rate down because:

- A high borrowing rate is not relevant to containing inflation any longer

- They have frozen the housing market, and there is too much on the line in keeping it frozen (i.e., affordability challenges, lack of new construction, its contribution to the economy, etc.)

- The Fed knows that trillions of dollars of loans across business borrowings, the bond market, and commercial real estate face rate resets in the next 12-24 months, and the economic damage of these loans resetting higher is monumental.

- Ummmmm, the U.S. Treasury Department (aka the taxpayers) faces a substantial increase in debt service costs if interest rates are not lower on the U.S. national debt.

- The strong dollar was a little too strong for their liking in terms of global competitiveness.

- See #3 and #4 and re-read them as many times as you think Powell and the FOMC will in the next year or so

What comes of quantitative tightening?

I would suggest that they keep it going at a low magnitude until credit spreads and other financial indicators force them to reverse. If they go too far or too long, then the indicators may cause them to revert to actual quantitative easing. If they somehow stick the landing here, which will be about luck, not skill, they may just “hold the line” with the balance sheet when they are ready – no more roll-off (tightening) or easing (bond-buying). This is an experiment. They don’t know what will happen, and neither do I. No country that has ever bloated its central bank’s balance sheet as a tool of injecting liquidity into its financial system has ever normalized the balance sheet later. But all of this is new, so like any experimental medical treatment, we don’t know what we don’t know.

Markets: What happens now?

Do lower rates make risk assets more valuable? In theory, yes. A lower “risk-free rate” boosts valuation as the earnings stream of the risk assets is discounted against a lower rate, boosting the valuation. But what if that has already been priced in (not much of a “what if” here)? And what are the offsetting issues that could be relevant to supposed valuation benefits? There’s No Free Lunch. What are the trade-offs here?

Let’s start with the easy part: Borrowers like it better when rates are lower. Less interest expense saves borrowers money. Does everyone feel they have mastered that economic epiphany?

Okay. Now for a shocking corollary. Those RECEIVING interest do NOT like lower rates as much as people PAYING the interest do. One person’s expense is another person’s income. Therefore, some actors are negatively impacted by lower rates, just like some actors (borrowers) benefit from lower rates. Now, who might the actors be who suffer from lower rates?

That’s right. Savers. Interest income recipients. And lenders – i.e., banks. Now, banks have to manage a spread because if they receive less in interest on loans but then pay out less in interest on deposits, they can be fine (this is called net interest margin). $25 billion of interest income per month has been generated in the last year or so, and it had been $0 (give or take) for much of the last fifteen years. Is this all zero-sum? To some degree, yes, but in the weeds, it is not as simple as saying, “Yay, there is less interest expense now.”

Will people or companies borrow more when the Fed Funds rate is 5% than when it was 5.5%? Not really. Especially if they believe [know] it is still going lower. But that general trajectory is stimulative. The key is finding the natural rate (i.e., in line with nominal GDP growth). A rate above that (tightening) or below that (easing) becomes a policy tool.

Who tends to have borrowed more money at variable rates in the public equity world? Small cap companies more so than large cap. S&P companies are paying 4.2% in interest as a percentage of total debt, but small-cap companies are now paying 7.1%. This will converge quickly.

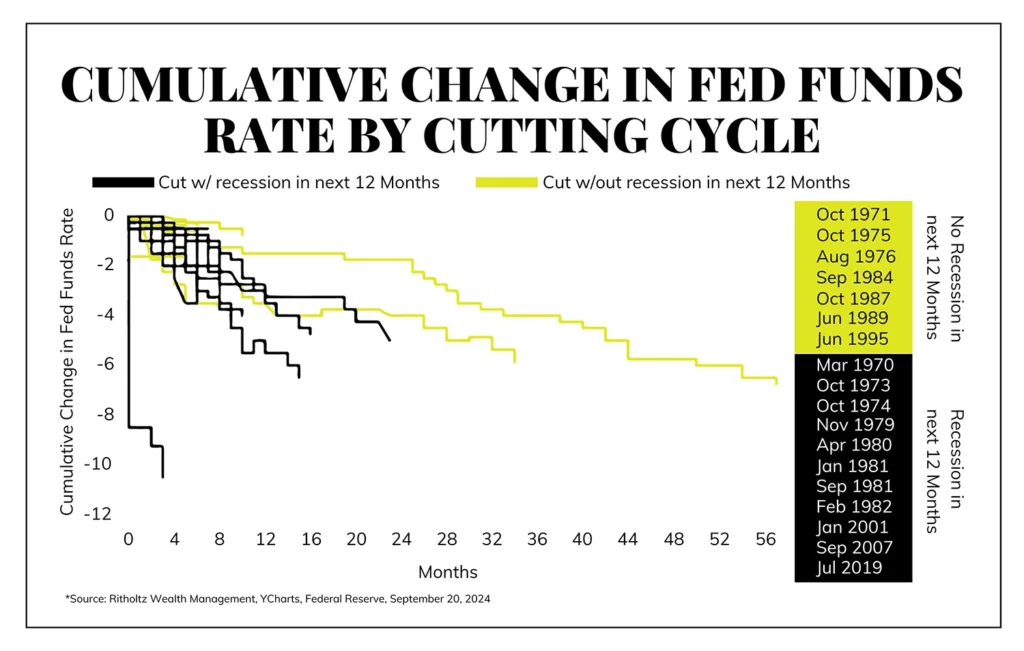

It is very hard to assess what lower rates will mean for markets by trying to use history because (a) History is filled with rate-cutting cycles beginning with economic recession, and that is not the case now; (b) History is filled with a mixed bag of results, so even if one wanted to use history as a predictor, it wouldn’t help; (c) Markets did not respond negatively during the last two years of tighter monetary policy, so expecting a reversal into upside is not totally logical this time; and (d) Valuations are already sky-high. I think I have mentioned that before.

Housing is the issue I am most flummoxed by. On one hand, I think there will be a lag until mortgage rates come down enough to unfreeze the market. I am spit-balling here, but I don’t see a 4-handle mortgage rate for a long time, and I reckon the Fed funds rate has to get to 3% or 3.5% before a 5% mortgage is possible. And then, do I think housing prices shoot higher because mortgage rates are lower? Not really. It MIGHT, for a brief irrational stint to draw in the, ummmm, eager (I am going to use that word more as a synonym for what I want to say). But I do believe lower rates will incentivize sellers to sell (in that they can borrow in their replacement property at lower rates closer to what they are paying now), which should unthaw the market. The only reason I don’t see that also catalyzing (in a sustainable way) a leg up in prices is that they are already too high.

Conclusion(s)

Back to quick bullets for the cliff notes:

- The Fed has begun a rate-cutting cycle that I believe will take the Fed Funds rate from 5.5% to 4.5% or lower by the end of the year and very likely to near 3% by the end of next year

- On this point, I must say that the fed funds futures market is adamant it will be 3% or even lower, and some people I deeply respect, like Rene Aninao of Corbu, do not believe we get anywhere close to that

- The Fed is easing monetary policy with interest rates but tightening monetary policy with quantitative tightening (bond-selling). This is the first time we have ever seen the Fed use two policy tools at odds with one another at the same time

- Quantitative tightening will come to an end at some point, and the circumstances around that and the response thereafter are what will next be a major catalyst to markets from monetary policy

- 2025 volatility will be enhanced as markets wonder, meeting my meeting if the 25/50bp discussions are live and what the terminal rate will be (3.5%? 3%? 2.5%?)

- Stock prices (at the index level) will come down to how long elevated valuations hold, not what the Fed funds rate does.

- Bond yields are not going back to 5%

- Housing can’t unfreeze until mortgage rates come down to 4.5-5%, give or take. Once it “unfreezes,” sellers become willing to sell because of replacement borrowing costs being lower, but that doesn’t speak to where prices will go.

- All of this is dependent on the economy staying out of a recession

Chart of the Week

This is the story of the tape. The bond market is predicting and requesting. The Fed is playing catch up. And the bond market wins in the end.

Quote of the Week

“There simply is no place for certainty in fields that are influenced by psychological fluctuations, irrationality, and randomness. Politics and investing are two such fields, and investing is another.”

~ Howard Marks

* * *

I am excited about the election edition of Dividend Cafe, which will be in your inboxes next Friday (the 27th), but I really did enjoy this week’s edition, too. This Fed stuff is just so fun for me; it is a little embarrassing. I welcome your questions and interactions, and I assure you that there is much more to come in the world of monetary policy and its impact on markets.

And yes, between now and the end of the month, we do have (a) The USC-Michigan game and (b) The special election issue Dividend Cafe next Friday. I love September.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet.