Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

The Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve met this week for their scheduled meeting and announced that … wait for it … they were not doing anything with interest rates. The market knew this was coming – futures have had a 100% chance of no increase or decrease in the Fed Funds rate at the January meeting for months – but markets went down -300 points after Fed chair Jerome Powell gave his customary press conference. The bond market went way up as yields dropped. And sure enough, stocks caught up to bonds the very next day as the Dow jumped +370 points.

Maybe this sounds to you like a lot of drama for one or two market days when everyone already knew what was going to happen, and you would be right. But the question that many are asking is – if it doesn’t matter, why does it matter? In other words, why is market volatility so high and press attention so high about when the Fed will begin cutting rates? Maybe traders do dumb and speculative things, but why do traders care about this so much? Why not focus on more important short-term betting odds, like whether or not Travis and Taylor are going to get married?

In this week’s Dividend Cafe, we explore the question of, “Well, does it matter?” And to understand if what the Fed does matters or not, we may want to understand what they do exactly.

This is a good one. So jump on into the Dividend Cafe.

|

Subscribe on |

First things first

What does it mean to say that the Fed will raise interest rates or cut interest rates? Do they get to tell banks what to charge? Do they set the yields at which investors will buy government debt? What exactly happens when the Fed announces a “rate decision”?

Well, the first thing to say is that the answer to those questions in the preceding paragraph is no and no (about banks and Treasury yields). The Fed does not set them – market forces do. But this is sort of incomplete in that what the Fed does heavily influences the outcome of mortgage costs, Treasury yields, money market rates, and so forth and so on.

The Federal Reserve has a previously mentioned committee called the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) that has been tasked with setting what is called the Federal Funds Rate. The Fed Funds rate is the “target rate range that commercial banks borrow and lend their excess reserves to other banks overnight.” This may seem like technical jargon (because it is), but when combined with other technical jargon, it becomes meaningful (even if still boring). Banks lend excess cash to each other, and that lending activity is the first step in profit-making activities. Banks cannot lend to other banks anything other than what exceeds their reserve requirements. They must, by law, hold their reserve requirements at the Federal Reserve (what makes the Fed the “central bank”). When deposits are above and beyond reserve requirements, they want to, you know, “make some money.” So they lend out to customers (holding those loans on their balance sheet), or they lend to other banks. The Fed Funds rate, by representing what banks charge each other, becomes the ultimate short-term “policy rate.” Some banks may be short in their reserve requirements so they can borrow from other banks who have a surplus, and out of this activity, money flows, and banks lend or don’t lend, etc.

Ignore the above paragraph if you want and allow me a succinct summary sentence that is a little too simplistic but, nevertheless, accurate: The Fed Funds rate is a rate the Fed sets to control economic activity up or down by influencing the level of activity banks do (or don’t do). A higher fed funds rate reduces the supply of credit, in theory, as banks borrow less when the cost is higher, and need to borrow less because their reserves are higher because their customers are borrowing less. Get it? Everything else is noise – the Fed Funds rate is a policy tool to control the creation and cost of credit – period.

Okay, why do I care again?

I won’t insult you with the easy part. Once the Fed Funds rate is set, a “benchmark” is in place from which other rates are set that clearly do impact the economy directly. The “profit margin” (spread) of riskier lending can be maintained with lower credit card rates if the Fed Funds rate, itself, is lower. The same is true of mortgages, business loans, etc. Now, whatever the appropriate “spread” is for various types of lending will be set by the particular risk profile of what we are talking about. Mortgages have all sorts of unique circumstances around collateral, borrower quality, protective equity, and so forth, and credit card debt (as unsecured borrowing) has entirely different risk characteristics. So banks, competing with one another, price the credit they will extend for different purposes around risk and reward, competition, presumed defaults and recoveries, and yes, around the baseline rate that is the Fed Funds rate.

So no, the Fed does not set your mortgage cost or small business loan, but, you know, they sort of do. It’s just not as direct as some make it out to be.

The question to ask is “why?”

So a lower Fed Funds rate, in theory, accelerates economic activity, and a higher Fed Funds rate slows economic activity, right? And more economic activity means more profits; therefore, a lower Fed Funds rate is good for stocks, and a higher one is bad for stocks, right? Well, not so fast …

There are two problems here. The second one is less important, but I need to say it, and that is the discounting nature of stocks. They price in today’s expectations about the future, not the news of today. So, it is always possible that rates can be high and economic activity constrained, but stocks go higher if the market senses that rates are coming down in the future (see: 2023). The inverse is true as well, of course.

But the biggest issue has to do with why the Fed may be cutting rates. In 2007 and 2008, the Fed was cutting rates like crazy, and markets got hammered. I mean, the lower rates were probably nice and everything, but when the world is ending, the cost of capital was sort of secondary to, ummmm, financial armageddon. The Fed was cutting rates because the economy was in deep recession. Good luck seeing stocks go higher in environments like that.

But the Fed was cutting rates in 1998 and 1999, and stocks were flying higher. Why do rates sometimes help? Well, a good economy that then gets an extra boost with a lower cost of capital is like a dessert that has extra chocolate sauce added to it. A terrible economy that is getting worse receiving lower rates is like lima beans having chocolate poured on top. The lima beans have to get out of the way until anyone can be happy.

Summary now

In 2024, we have two things at play:

(1) A good economy about to receive rate cuts, BUT

(2) A market that already knows it is coming

The second point is a by-product of post-Greenspan monetary policy. The market knows ahead of time what is going to happen almost always. In fact, the market leads the Fed in most cases as to where they ought to go.

Does this mean it does not matter? Not exactly. It means something asymmetrical. Here is what I mean by that – if the market expects rate cuts and does not get them, the market could be disappointed and sell off; AND, if rates stay too high for too long (above the natural rate that is the market level where borrowers and lenders naturally transact), then fundamental economic erosion is inevitable.

For reasons I have written about over the last year, the Fed’s tight monetary policy over the last 18 months has been limited in how much “damage” it has done. Consider:

- Many corporate borrowers had their borrowing set at fixed (low) rates already

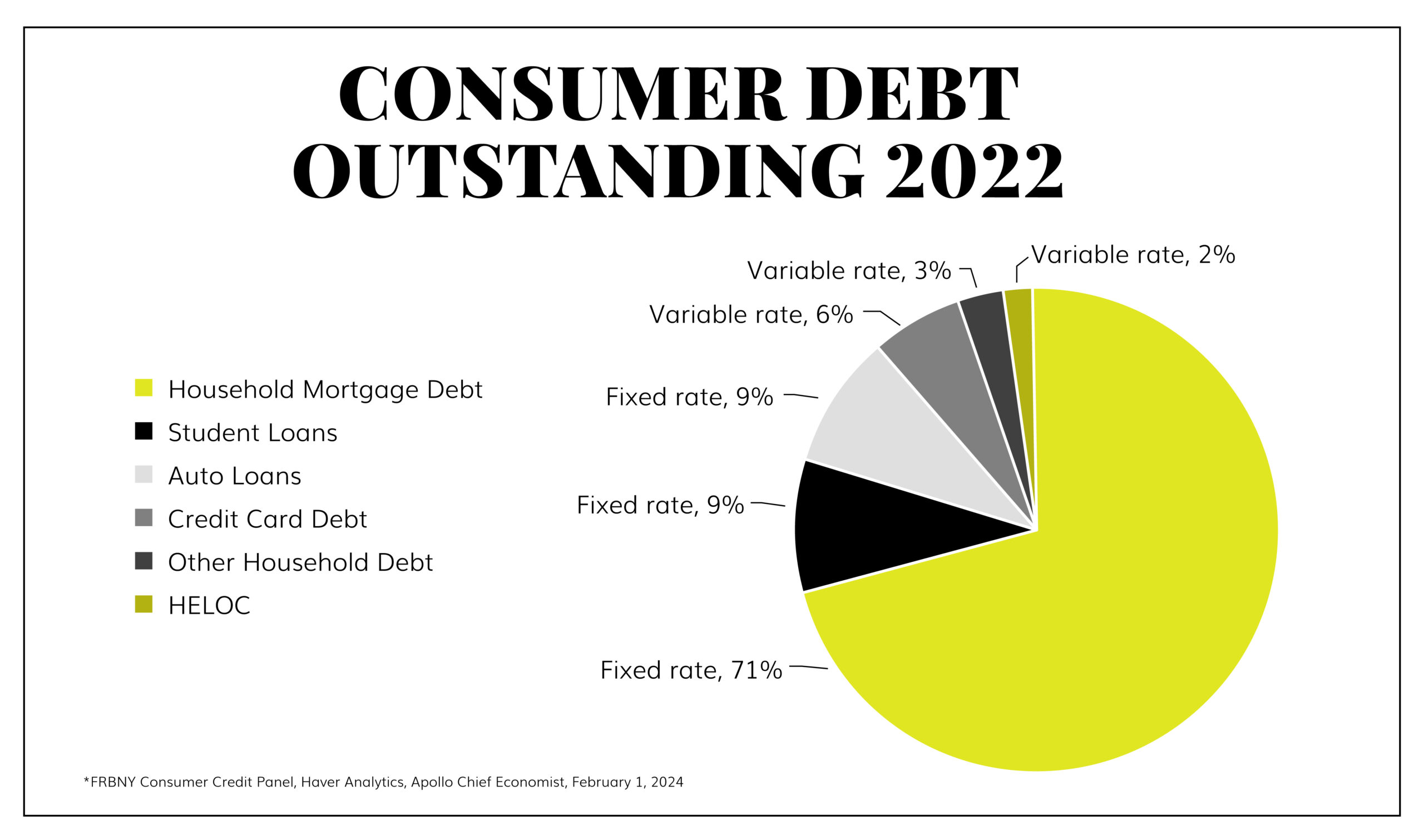

- Nearly all mortgage borrowers had very low rates that were fixed for quite some time

- The majority of individual borrowing is fixed (see Chart of the Week below)

- A re-opened economy kept surging with decent business activity and a consumer that was soaking it all in, employed, well-paid, and even able to tell their boss when they planned to show up for work (if at all). Good times!

This is not to say there was not an impact. Regional banks got caught offsides with their bond holdings. New construction and new commercial development were severely limited. Even though a high proportion of corporate borrowing was fixed, plenty of bank debt was variable and pushed up borrowing costs for millions of small business borrowers. And residential sales dried up as buyers and sellers went on strike, basically freezing the housing market.

So the Fed basically did what it wanted to do – it slowed certain parts of the economy, but it didn’t put it into a recession. Was this brilliant? No, not really. It takes luck, and it takes on risks that are unpredictable. It distorts prices. It plays with fire. And it puts into the minds of economic actors that the Fed is a marginal player in economic activity (as opposed to a slightly more sensible choice – those participating in the economy!).

But what we know right now is that rates are coming down, though we do not know exactly when or by how much. And that, my friends, is the lay of the land.

What to do as the Fed does what it does this year?

There may be collateral (lagged) damage to the period of Fed tightening. I don’t see it yet, but I can’t see what isn’t there (yet) – and neither can anyone else. They may cut more than expected, but I doubt that (this year). The economic benefits of easier monetary policy are not a future boost to risk assets because every man, woman, and child in America is already banking on them. The parts that are unknown are where we go into the future – what sort of productivity does the economy have ahead that may determine organic economic health, and from there, necessitate a Fed response. The unknowns that do not matter are “25 vs. 50 basis points” in “March vs. May.” That’s all noise. Up. Down. A good day. A bad day. You’ll have more fun tracking Presidential election polls than that silliness.

What will matter far more is not what the Fed does this year but what happens in the important stuff that impacts the Fed’s decisions in the future. In other words, it may be about to get (for a period) “how it should be.” Whatever that may mean.

Chart of the Week

A great illustration of why Fed policy has not been as restrictive as some expected. When borrowing costs are fixed, higher rates don’t matter for anything other than new debt.

Quote of the Week

“The reason that ‘guru’ is such a popular word is because ‘charlatan’ is so hard to spell.”

~William Bernstein

* * *

I am writing this Thursday night from my hotel in Miami, where I am about to give one speech tonight and another one tomorrow morning before heading back to New York. I am looking forward to the weekend where I have a special project in front of me involving about 15 of my late father’s sermons. I will leave you in suspense, but I am ready. My hint: It has to do with the most full-time worker I ever met!

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet