Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

Today we are going to talk about something no one else seems to be talking about, and that may be one of the worst things imaginable for financial media ratings if it ever gets out. It is not controversial. It is, to me, somewhat obvious. But it is highly counter-cultural, and as I say, for many, it is highly problematic.

Jump on into the Dividend Cafe!

|

Subscribe on |

Lights, Camera, Action

When I first started getting invited to do television appearances on various financial media outlets, there was no question they wanted to ask more commonly than, “is the market going up or down?” Sometimes one could spin their answer to the timeline you wanted to address it in, but more or less the implication of a financial anchor asking you, “is the market going up or down?” is “tomorrow” or “next week” – and maybe for a more respectable journalist, “next month.” But beyond that? No. Short-term shows living or dying by short-term ratings are not asking a question about long-term market returns.

Fortunately for me, I got invited back despite never answering that question once to anyone’s satisfaction. I ended up becoming “the dividend guy” for Stuart Varney’s hit show on Fox Business, where I get to speak the truth, talk about my real passion and competence, and not have to answer questions about ultra-short-term issues that no one on God’s green earth has anything intelligible to say about. It took a while, but for some shows, anchors, and producers, they ended up finding me to be a resource on the nexus of public policy (politics) and markets as well, and for others, I definitely get included in various discussions on the Fed and monetary policy. So you will note that the vast majority of what I talk about on television or print media has to do with dividend growth stocks, the Fed, and the impact of policy on markets. It evolved that way organically because (a) I have beliefs in all these domains I feel confident to offer and defend, and (b) Somehow, others on the media side agree with what I said in A. The shows are networks that want me to say what the “hot trade” is that week or what the “weekly outlook” is for the market and do not invite me to be on, and I accept their terms.

If I am ever asked what I believe the market is doing this week or this month, or this quarter you will pretty much always hear some version of the same answer – that I do not know, that I do not care and that no one else knows either. If I have had enough coffee that day, I may add a little bite to my answer like, “I will not lie to you by even pretending I know the answer to that,” or “the only people who claim they can answer that are grifters or charlatans.” If I don’t like the anchor, I might even say, “to even ask that question is foolish and dangerous,” but candidly, I wouldn’t really try to embarrass anyone on air (well, not an anchor anyways), and I am mostly in comfortable, likable situations with anchors these days (I pretty much don’t get asked to be on shows where they don’t like me and where I don’t like them).

This is not a Dividend Cafe about my media policies and posturing, though. Rather, this media protocol from yours truly is an off-shoot of a real investment truism that matters beyond a journalistic presentation.

More than meets the eye

There is a point embedded in what I am saying so far that you may already detect, that I have shared many times, and that is applicable in all seasons of investing – and that is the inherent unknowability of short-term market movements. A better way of saying this may be “the lack of wisdom in formulating an investment policy around short-term market movement expectations.”

I have said a thousand times that whenever someone tells me, “I called XYZ,” I always want to say, “can I see the confirms?” [that is industry jargon for the “trade confirmations” that get generated by law for any trade that takes place – buy or sell – for every trade]. Many people seem to confuse saying at a cocktail party after their second cosmo, “I bet XYZ is going to do well,” with actually buying it, sizing it, placing the trade with risk capital, and even having an exit plan for their Einstein-like call. But there is more to my snark about seeing the confirms than just pointing out that, ummmmm, they “called it” without a trade is sort of like me “knowing a big, strong, tall, fast basketball player will do well” – turns out you have to name names, teams, games, and players. Specificity is a real inconvenience in the land of cocktail party bull-sh&^$ers. But let’s say one did “call something” – why does “seeing the confirms” help? Because it de-geniuses all of us because, alas, when you get to see the great trade for the XYZ cocktail party trade, you also get to see the ABC trade that was, well, not so good. And while Vegas is somehow still standing despite all the millions of people that seem to have never lost there, the person who “called something” can’t hide behind the selective nonsense of only sharing one or two good stories when their reality is buried in the confirms. But I digress. [Those who want to hear of my stories here can look forward to a book I will write in 30 years on the subject, chronicling the greatest hits of BS I have gotten to hear over the years, with names altered to protect the emotionally fragile, of course].

Wait, where was I? Oh yes. Short-term market calls. They’re for those in search of validation who will not cough up the confirms and no one else.

Past is prologue

I would suggest that there is a new flaw in the question of “what is the market about to do?” that goes beyond the mere problems of short-termism and unknowability I have highlighted so far. Embedded in the question may be a premise that is deeply flawed – that markets either go up or go down. And in reality, it may be time for us to consider the possibility of an argument for a “third way.” It may be time to consider a period of directionlessness.

All the history you could ever need

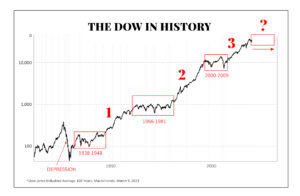

I want you to note a few things about the chart below that do not answer the “question mark” at the far right of the chart but do provide epistemic certainty about the past. The chart is of the Dow Jones Industrial Average for the last one hundred years. The violent downswing from 1929 through 1933 is easy to identify, and we know it as the Great Depression. It was followed by a violent upswing from 1934-1937 (the bounce out of the Depression), and then from 1938-1948 (which, of course, included World War 2), you had an essentially flat market. 1949-1966 was the first secular bull market I am highlighting below (the market was up 4x in that time period). But then what happened? A lengthy period of “directionlessness.” Yes, there were big moves down, and big moves up along the way, but for 15 years, you essentially had a flat market (1966-1981).

*Dow Jones Industrial Average 100 Years, MacroTrends, March 9, 2023

Then we had the bull market most of us grew up with – basically, the uninterrupted bull market of the 1980s and 90s (#2 above). Now, yes, there was that little “Black Monday” thing in 1987, and there is no one who was invested for that whole period who felt that there was no downside volatility along the way, but the chart speaks for itself. A textbook bull market coupled with wonderful economic expansion.

We then entered a “lost decade” – that is, 2000-2009, bookended by the tech bubble crash and the housing bubble crash. It had a huge drop, a huge rally, and a huge drop, but from point A to point B – flat.

And then we get to more modern times, the bull market that may be what many of you feel is “normal market activity” – that is, 2009-2021 (#3 above). The bounce out of the Great Financial Crisis, zero percent interest rates, Fed liquidity run amok, and massive multiple expansion. Nothing could stop it, not even a global shutdown and the COVID pandemic until 2022.

And. Here. We. Are.

What follows secular bull markets?

Look at the chart again. Look at the periods I have labeled as #1 and #2. In each case, what preceded and what followed? Prolonged periods of flattishness – a prolonged period of directionlessness. Sure, some rallies here and there and some sell-offs here and there, but net net, no clear and trended market identity.

Saying the quiet part out loud

But wait, there’s more.

The market was NOT really “flat” from 1966-1981. And it was not flat from 2000-2009. Dividends provided the return. Where there were dividends (above the price level reflected above), there was a return. Where there was not, those prices embedded in the chart were the entire return.

The S&P 500 yield is currently 1.7%.

You do the math?

“What is your forecast?”

I am not answering that question. I am not suggesting we are a sure thing “directionless” up and down market to come. I am happy to analyze both bull and bear prospects. But I would just say that this directionless scenario has some merit in history and fundamental dynamics. Read on.

Bull Durham

Could some significant extension of the bull market we have been in come back? I would not bet on such a thing, but it’s not impossible. I suppose I would say this, though. IF such a thing happened – a renewed secular bull market continuing the upward trend of 2009-2021 – it doesn’t seem possible that it would be driven by the same things which drove that bull market. The S&P 500 went from 13x to 22x in its valuation; I don’t think we are going from nearly 20x to over 30x. Earnings tripled from 2009-2021 (roughly $70/share to roughly $200/share); I don’t think we are going to $600/share. The Fed had rates at 0% for 90% of this bull market; I don’t think we are going back to zero.

So if we get extended innings of a bull market, I think it becomes less liquidity-driven and less valuation-driven and more event-driven. And to me, the “event” that I think would have to trigger it is a capex-super-cycle, a productivity boom birthed by industrial expansion and digital innovation. Perhaps on-shoring, near-shoring, re-shoring, and other such aspects of supply chain fortification catalyze this? [I have a new Dividend Cafe to write]. But no, the policy regime right now is not screaming for such to happen, as needed as it may be.

Why was this section called “Bull Durham”? Because I was discussing the “bullish” thesis for markets, and the 1980’s movie, Bull Durham, starring Kevin Costner, Tim Robbins, and Susan Sarandon, has the word Bull in it. That’s it.

Bear Down

Could we enter a full-blown bear market? We are sort of in one, actually. The Nasdaq already drew down -35% and the S&P -23%. Could the Fed break something, credit spreads widen, and a deep recession break out? Well, sure, but that is always a possibility. What seems most likely now is that “good stuff” went down but not to Hades’ levels, while “bad stuff” got appropriately put out to pasture. Volatility may stay put, but a true sustained bear market with earnings contraction being, at worst, down single digits would be unprecedented.

Why was this section called “Bear Down”? Because I am a portfolio manager, not a copywriter. Cut me some slack.

Midtown is lovely

The historical record may be indicating a period where we have nice rallies, real sell-offs, and a generally choppy disposition. The words “range-bound” and “flattish” have not been uttered a lot, lately, but I would not be surprised to see them become a bigger part of our financial lexicon in the years to come.

There are times you have to pick one way or the other …

and times when running the wrong way at a fork in the road can do real damage.

And there are times you can be just content in “midtown.”

The Dividend Conclusion

I believe that “flattish” markets over sustained periods of time can be very frustrating for index investors and often fatal for speculative investors, but they can be unbelievably rewarding for dividend investors. Most importantly, regardless of investment strategy, it can be very healthy to understand the distinct possibility of such an event. They are significant parts of investment history (as the chart above shows). Calibrating expectations to reality is a good life skill. Having a strategy that meets the moment is an advanced life skill.

To that end, we work.

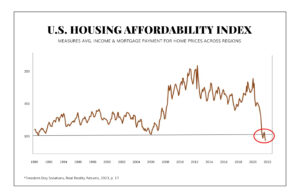

Chart of the Week

Affordability is a good thing for homebuyers. Stop me if I am going too fast. Low affordability means prices have to come down, or there will be less activity.

*Freedom Day Solutions, Real Reality Returns 2022, p. 17

Quote of the Week

“It does not matter how frequently something succeeds if failure is too costly to bear.”

~ Nassim Taleb

* * *

I am flying home from New York City after a long time in that home and office. I had a successful trip for what I wanted it to accomplish, and I am ready to go back to the land of bad food where it is so much easier to eat light.

Do reach out with any questions about this week’s Dividend Cafe. As you know from my media appearances, there’s only one question I won’t answer. =)

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

www.thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet