Dear Valued Clients and Friends,

The third quarter of 2025 will come to an end next week. I do not believe very many people would consider it to have been a boring year (whether the subject is markets, the economy, or national politics). I, of course, do not know what lies in store for Q4, but I do not suspect it will be boring. And one thing that does happen every year in Q4 is the beginning of my deep reflections into the “year ahead.” Quarter-by-quarter and year-by-year, the world keeps turning, and I feel it is a part of my job to do my very best to understand it all. And I love my job.

Tariffs, questions about AI capex, a changing approach to the Ukraine/Russia war, volatile labor market data, a new earnings season, and any number of similar issues are in the headlines for a season and generate legitimate questions and interest. Various issues and concerns come and go, but they dominate for a period that has the effect of crowding out considerations of other issues that may be less transitory and more substantial. I try to write about Japanification a lot because I believe it is a multi-decade story, and paradoxically, we seem less able to consider multi-decade stories than we do multi-quarter or even multi-week stories. Attention spans are funny that way.

Today’s topic is not a “come and go” story. It is one of those secular themes that ought to be frequently touched on in the Dividend Cafe. The reason to cover it here is because it has profound relevance to macroeconomic matters and will for years to come. It is also a cultural story that overlaps with all sorts of social and political tentacles. The issue of weekly jobless claims and monthly BLS data can certainly be considered one of those “cyclical” stories that come and go, but that is not the subject of today’s Dividend Cafe. Today, we look at whether or not one of the major stories for the American economy in the years and decades to come is also one of the major stories of American culture and politics: The amount of workers in the American population.

Today’s read is not overly long, and it is unlikely to impact the stock market over the next three days or three weeks. But it is going to be discussed and analyzed and studied for three decades, and candidly, has already been a story in development for at least two decades. So let’s do our part to transcend the transitory and dive into the more entrenched things that matter.

Let’s jump into the Dividend Cafe …

|

Subscribe on |

American Economic Exceptions

The labor market is crucially important right now in terms of macroeconomic analysis, but that really has always been true. In a market economy with diversified access to goods and services and diverse capacity to produce them, something resembling full employment is a permanent objective. It has proven to be reasonably achievable – not that we ever have 0% unemployment, but unemployment in non-recessions is generally very low, and the amount of time most workers have to be unemployed in our economy has historically been manageable (again, by definition, things are different in recessions). This allows most of our economic analysis to assume that a manageably low unemployment level is sustainable, and therefore, other conditions can be the main drivers of economic growth.

In other words, we take for granted that something near full employment is usually achievable, and that we can focus on other knobs to generate a standard of living worthy of our extremely prosperous society. This means that cyclical periods of economic downturn become very problematic. Rather than worrying about the desire for ever-growing wage growth, which comes out of ever-growing production of new goods and services, cyclical downturns (recessions) undermine the general premise of full employment and create really unfortunate periods of social, economic, and political angst.

Our history of recessions is that they end, although there is ample debate over what ends them. Keynesians believe the intervention of fiscal policy from the government is needed to counter-punch contractionary moments in the economy. Others (yours truly included) believe that recessions are self-correcting in a true market economy, and that government interventions actually exacerbate problems (or create new ones altogether). Regardless, we function as a society with the belief that recessions can be (a) Rare and (b) Short-lived. Since the Great Depression, we’ve navigated most of these challenges fairly well, with the credit implosion of 2008 being the one existential moment that will be in the history books (I can’t let myself get distracted by this topic now, but I have written plenty over the years).

I do not mean to suggest that recessions do not matter. Cyclical recessions still bring real challenges to real people, and regardless of the significant differences of opinion in how they ought to be addressed (or not addressed) by policymakers, no one should ever dismiss the gravity of a recession. However, the cyclical angst a recession creates for some is different than a macro and structural tear in the underlying economy. Many countries see job erosion as something that metastasizes in their economy, lasting longer, going deeper, and spreading wider than we have historically experienced. We have the productive capacity and self-correcting mechanisms in our robust free enterprise system to repair damage from a spike in unemployment. Dynamism covers a lot of pain, even if it can take time to do so. And the American economy is far, far more dynamic than any other economy on earth. This leaves job erosion as a serious thing for people in short-term cyclical windows, but something that has not historically become embedded into the economy and become irreparable.

But please note what I said multiple times in the preceding paragraphs: jobs, employment. What I was not referring to was workers. A job is what a worker wants. A worker is one who wants a job (or has one). We have always devoted more of our national attention to the former than to the latter.

We have looked at the labor market for a long time as a demand issue (jobs), but the paradigm shift we are living through suggests it has become a supply issue (workers).

And that is the subject of today’s Dividend Cafe.

Here and Now

The short-term concern about the health of the job market is a perfectly legitimate one. If there are cracks in our labor market now, as some (not all) metrics suggest, it calls into question the sustainability of GDP growth next year and pokes at those cyclical concerns about our economy.

It would be doing so at the same time that unanswered questions exist about the impact of tariffs on the economy, capital flows, and productive investment. For either partisan reasons (understandable even if annoying) or a more innocuous lack of understanding, many are looking at the current quarter-by-quarter GDP data as if it tells us a helpful tale about current economic conditions. But in reality, each quarter has gone back and forth lately, capturing the distortion of elevated imports followed by a contraction of imports, as one-time events skewed by attempts to front-run or play cat-and-mouse with expected or actual tariff announcements. They are lumpy, they are frankly silly, and they do not tell you, “hey, this economy is _____ right now.” There are questions, and they are not answered clearly in the data, as the BLS’s new job creation looks dismal, but the initial weekly jobless claims look benign.

Calling a Spade a Spade

The “unemployed” are those who do not have a job. But to count as “unemployed” in the “unemployment” rate, it is not enough to be unemployed – you have to want a job, and not have one. Retired people will often say, “I am retired,” or “I spend a lot of time golfing,” or “I do some non-profit volunteer work,” or “I now spend my time collecting seashells” (if you know, you know), but they do not generally identify at parties as “I am unemployed.” There is a classification difference for good reason.

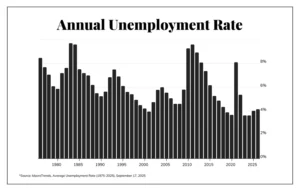

The average annual unemployment rate in the United States over the last fifty years has been 5.7%. Besides the COVID spike in 2020, it has been between 3.5% and 4% for the last seven years.

The big spike in unemployment following the financial crisis (6-10% unemployment from 2008 to 2015) has been followed by a much lower unemployment rate. So why am I writing on this subject at all?

The challenge lies in the inactivity rate, which refers to the working-age population not in the labor force at all. This simply means they do not have a job and are not looking for one.

This could include retired individuals, as well as the disabled, full-time students, and caregivers (those caring for family members who are unable to work). The above chart, however, does not include anyone over the age of 64. The move from 22% to 25% (3% of 212 million people, which is over six million people) is only marginally related to retirees. It is almost entirely voluntary inactivity.

The labor participation force shows a pre-crisis decline of nearly 68% to a post-COVID leveling of 62%.

But in order to really make the point I believe most needs to be made, it is useful to isolate the prime working-age population (25-54). Excluding those 15-24 ignores the data of part-time workers, teenage workers, and young adults who may be students looking for work, and all of that actually matters (I am a huge believer in those between the ages of 16 and 24 having part-time and summer work), but it does bring some other noise into the data we can go without. And those over the age of 54 are far more likely to be in retirement, and certainly those over 65, as baby boomers enter that phase of life have been leaving the workforce for fifteen years now. It reduces noise to take out that demographic, too.

Isolated to ages 25-54, the inactivity rate is a stunningly high 11%. Said inversely, the labor participation rate for that demographic has gone from 98% to 89% over the last sixty years.

But allow me to point out: the ages of 55-64 are hardly “guaranteed retirement years” – yet that inactivity rate is a stunningly high 27.5%. The much higher inactivity rate among those over 65 and over 75 is far more correlated with retirement. I am not buying it for those 55-64, but I will leave that statistical atrocity out of my assessment for now, because it isn’t needed to make the point.

I also did another bait-and-switch above. The labor force chart above includes only MEN. The 11% inactivity rate for those 25-54 is for men only. And why did I do this? Because there are 65.2 million men between the ages of 25 and 54 in our country. A 10.9% inactivity rate means there are basically 7 million men between the ages of 25 and 54 who are neither working nor looking for work.

Why isolate it to men? Because the decades of one’s 20s and 30s are the ages when many women have babies, and the data would be impacted by women who leave the workforce for this purpose. The inactivity rate for women past child-bearing years is actually UP +20% over the last forty years!!! The labor participation rate for women in prime working-age years is at an all-time high!! It has remained between 70% and 80% for the last few decades, when women working outside the home became far more prevalent. Currently, that participation rate is 78%, the highest on record. To include that data in our purposes would neuter the impact and fail to capture the cross-narrative that, actually, there is not a decline in women who want to work. Quite the contrary!

When we cogently isolate the data for men aged 25-54, we see that they account for 100% of the aforementioned increase in total inactivity rate.

What is Going On?

Median pay adjusted for inflation has increased. This increase in inactivity is not related to frustration over pay (at any kind of macro level). Only 3% of that 10% (0.3% of the total) are classified as “discouraged workers” (those who have stopped looking for work because they became too frustrated after a period of time at the lack of opportunity).

The Mercatus Center at George Mason University commissioned a comprehensive report on the subject several years ago. The 75 pages of data are overwhelming for their comprehensiveness, but also for the clarity and objectivity of what is demonstrated. The increase in disability claims in this period of inactivity rate growth is a near-perfect correlation. Now, the percentage of those inactive who are disabled has actually not changed much, but as we have already covered, the total number has exploded. So if the percentage of that increasing number of inactive who are disabled has stayed the same, it means that the number of disabled inactives has moved higher, in concert. And that increase is a direct response to the massive changes made in eligibility for SSDI benefits (the Disability Benefits Reform Act). There are ample studies about the correlational data of increased disability claims in the face of improving public health, exercise, and mortality, including the near exclusive role of mental/emotional health claims versus claims related to physical infirmity. I have provided the link to 75 pages of data for those interested, but I do not feel it a stretch to conclude that all of this points to a cultural shift.

It would be easy to blame this increase in inactive men on matters of race, or education, or geography. And in all three cases, there are ample political incentives to do just that. The data, however, does not provide any such conclusions. The increase in this voluntary inactivity of which I write is just as statistically prevalent for a 50-year old with a college degree who previously worked a white collar job as it is a high school dropout in a rust belt state. Attempts to attribute this increase to a decline in manufacturing are not found in the geographical data.

The common themes are that there is some sort of transfer payment or social safety net involved, and that there is substantial correlation with family situations. On that latter point, 58% of men ages 25-54 are married, but only 37% of the men classified as inactive are. I will leave it to readers to do their own speculation about the chicken or the egg, but statistically we know that various support programs are subsidizing greater inactivity among 25-54 year old men, and that a very disproportionate percentage of these men are unmarried.

I would hope it does not seem controversial to suggest from this that some form of social safety net reform (starting with disability programs) would be advisable, and that strong families seem better correlated with labor activity, just as labor activity seems correlated with stronger family presence.

Wrapping it Up

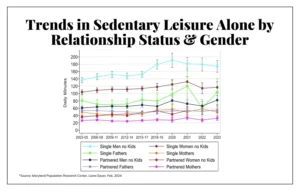

I do not imagine that the online world, in which more and more people are trying to live, is going to help. Indicators abound that antisocial behaviors are enabled, if not actively promoted, by increased online activity. Liana Sayer at the University of Maryland did an exhaustive study of sedentary (non-physical) leisure activities (video games, screen time, etc.) by various demographics, and you will not be shocked to see which demographic ranks highest:

I do not have a way to measure the exact economic consequences of voluntary inactivity amongst prime working-aged men in our society. I do, however, know that public policy is almost entirely focused on treating our job market issues as if they are, and will continue to be, demand-oriented (i.e., the demand for workers from employers). This strikes me as a crucial mistake in a period where we see more and more supply-oriented challenges (i.e., the supply of available and willing workers).

Those advocating for a universal basic income may be addressing a problem we do not have (a lack of jobs) by exacerbating a problem we do have (declining interest in work).

Those pushing for greater access to various tools of a social safety net may very well be increasing incentives for voluntary inactivity.

And those afraid of discussing personal responsibility, agency, and self-reliance may not only be missing out on the message that is the need of the hour, but they may also be missing the message the economy needs more than anything else.

Europe is filled with beautiful cathedrals in which no one worships. Is America about to build plentiful factories in which no one works?

Quote of the Week

“An excellent plumber is infinitely more admirable than an incompetent philosopher. The society which scorns excellence in plumbing because plumbing is a humble activity, and tolerates shoddiness in philosophy because it is an exalted activity, will have neither good plumbing nor good philosophy. Neither its pipes nor its theories will hold water.”

~ John Gardner

* * *

I am extremely excited for next week’s annual money manager week here in New York City. 20+ meetings with some of the best bond managers, hedge fund managers, private equity managers, and macro thinkers in the country. Brian, Kenny, and I are locked and loaded. And next week’s Dividend Cafe will bring you the best insights that the week generates!

And in the meantime, I close out with more than a passing nod to hard work, the dignity that lies therein, and the economic growth that can only be made possible by such human endeavor. It is, always and forever, work that not only feeds our stomachs, but feeds our souls.

With regards,

David L. Bahnsen

Chief Investment Officer, Managing Partner

The Bahnsen Group

thebahnsengroup.com

This week’s Dividend Cafe features research from S&P, Baird, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and the IRN research platform of FactSet