I love good questions.

The type of questions that stop you in your tracks and really make you think.

Not a cornering question nor combative one, but an inquisitive one that is birthed from the inquirer’s true curiosity. For me, this is how I learn – pulling on a particular topic thread to get a deeper understanding of the nuance.

Sean Latimer is my most frequent co-host on the Thoughts On Money Podcast, a dear friend of mine, and a colleague here at The Bahnsen Group. Sean asked me on a recent podcast one of those GREAT questions that I am referring to. We were discussing the recent rise in interest rates and its impact on the stock and bond market. Sean asked me if the higher yields on bonds have changed my perspective on Expense Based Planning (EBP). EBP is a term I coined for my approach to portfolio design. You can find more on the topic here: The Madness of Methods.

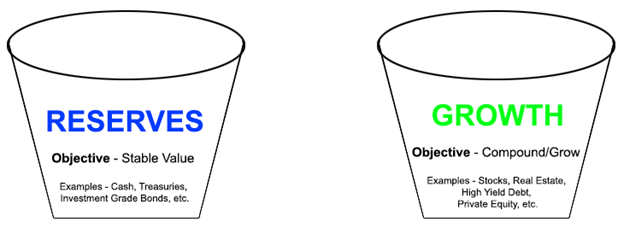

The basics of EBP are simple. Investment assets are bifurcated into two different categories – assets that are set aside as reserves or a safety net and assets that are allocated to grow and build long-term wealth. The reserves are always expressed as a multiple of expenses. So, for example, if an investor has $5mm of investment assets and their expenses/withdrawals are $200,000 per year, we might set aside $600,000 (or 3 years of expenses) in reserves. EBP also incorporates other layers of safety nets that range from dividend/interest income to access to lines of credit.

Why I became such an advocate of EBP was two-fold. First, through thousands of planning conversations, I had become keenly aware that investors desire two attributes from their investments – stability and growth. I found myself often telling clients this little quip, “Investors want stability and growth; they can have one, but they can’t have both.” It was my way of saying that one investment (allocation) was not going to satiate both of these desires – price stability and meaningful growth. EBP allowed me to isolate assets into these two different categories; reserves to provide the needed stability and a separate designation of funds for long-term growth objectives.

The second reason I was attracted to EBP is that I felt like I needed to reject the classical approach to portfolio design. I saw most of my peers throughout the industry take this approach to financial planning: the client completes a risk survey, the risk survey determines risk tolerance matched model portfolio, and the financial plan is run using historical returns of this model portfolio. In my experience, these risk surveys were difficult for the clients to understand, yet they were the primary source for the portfolio design. Additionally, these financial plans were using return assumptions that were heavily inflated, and clients were not likely to achieve these expected results.

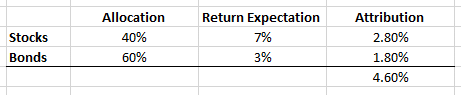

Here is another way to think about it. Let’s say your financial plan – based on your expenses, life expectancy, taxes, inflation, etc. – requires a 7% rate of return. Then let’s say you filled out a risk survey that concluded that you did not want to experience greater than a -20% downside in your portfolio. We will use rough estimates here, but we will assume that the peak-to-trough downside to the stock market in 2008 was in the -50% range. This means if you only want to experience a -20% maximum, then you can’t technically own more than 40% of your portfolio in stocks based on how stocks have behaved historically (e.g., 2008). Let’s then assume that the other 60% is allocated to bonds. If the average planner believes that stock return expectations over the next decade are 7% and the average bond returns are 3%, where does this leave this 40% Stock 60% Bond portfolio?

*for illustrative purposes only

This outcome (4.6% return) is well below the 7% target of the financial plan, and this shortcoming will compound to create a significant deficit for this retiree.

Again, my affinity to the EBP approach is that the design starts with the expenses/withdrawals in mind and the outcome of the design determines the expected downside. Yes, prior to implementation, the investor will need to agree to that defined tolerance, but I assume one would be more willing to “endure” if it was clear that their plan depended on this fact.

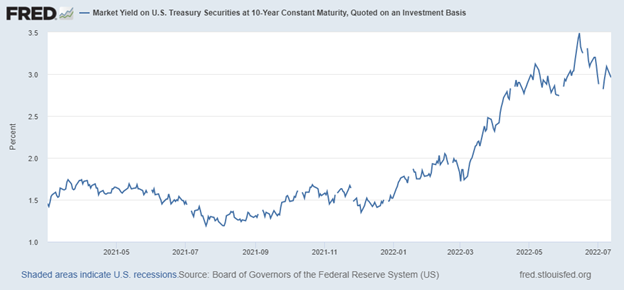

Now, let’s come full circle and return to Sean’s question. Does a higher yield on bonds change my perspective on Expense Based Planning (EBP)? When I originally penned my article (The Madness of Methods) on March 12th, 2021, the yield on the 10-year treasury was nearly half of what the yield is today, hence the reason for Sean’s question.

For some advisors, EBP became a method to prudently add a larger allocation to “risk assets” to help drive the expected return on an investment portfolio. Sean wanted to know if, as he sees bond yields become more meaningful, does that change my perspective on how I go about using/implementing this approach. The simple answer is no. The rise in rates, from my perspective, has just helped to provide some inflation relief to what I deem the “reserves” bucket.

As clients can attest to, during my portfolio design process, I will often draw these two buckets:

*for illustrative purposes only

Our design conversation will center around first filling the reserves bucket with sufficient assets to cover the desired level (always measured in years of expenses/withdrawals) that matches that particular client’s comfort level. Then anything we would consider allocating to in that growth bucket has to meet the criteria of what I call the-reasonable-person-expectation, that is to say, that a reasonable person would expect this investment return on this allocation to be greater than 7% over the next decade. This is not to guarantee that this will be the outcome, but rather that you could create a reasonable argument based on current valuations that this return target would be achievable.

So, this rise in interest rates didn’t change the categorization of these assets in my methodology but instead just added a slight boost to the yield on what I deem “reserves.” Now, it is important to mention that we see this boost from a nominal perspective. Still, on a real basis (accounting for inflation), this increase in yield does not fully accommodate for the rise in prices (inflation) we are seeing.

Perhaps the simpler conclusion is that I am still very much an advocate for the EBP approach to portfolio design. As mentioned above, I’ve come to this conclusion based on my dissatisfaction with the other approaches that I have seen throughout my career. As a financial planner, I believe this approach (EBP) really helps to wed the investment portfolio and the financial plan in a very complementary fashion.

I am sure today’s dialogue has sparked some questions for you, and I encourage you to email over any questions and comments (). As always, I appreciate your readership and look forward to sharing more of my Thoughts On Money next week….